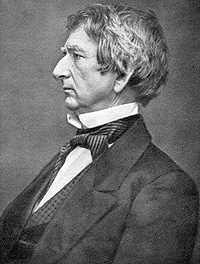

Edward Bates, who was slated to become Attorney General in Mr. Lincoln’s cabinet, wrote in his diary that he regretted that New York Senator William H. Seward had decided to become Secretary of State. “Not that Mr. Seward personally, is not, eminently qualified for the place, in talents, Knowledge, experience and urbanity of manners; but, at the South, whether justly or unjustly, there is a bitter prejudice against him; they consider him the embodiment of all they deem odious in the Republican party. And at the North and in the N.[orth] W.[est] there is a powerful fraction of the Rep[ublica]n. Party that fears and almost hates him — especially in N.Y.”1

Nearly three and a half years later, another Cabinet member, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, wrote: “Mr. Seward sometimes does strange things, and I am inclined to believe he has committed one of those freaks which makes me constantly apprehensive of his acts.”2 Welles wrote in his own diary of Bates’ evaluation: “Mr. Seward has been constantly sinking in his estimation; that he had much cunning but little wisdom, was no lawyer and no statesman.”3 On another occasion, Welles wrote that “Seward is a trickster more than a statesman.”4 Welles, who was frequently critical of his fellow Cabinet members, peppered his diary with special complaints about Seward — noting at one point in the fall of 1864 that a Seward recommendation was “a specimen of the manner in which the Secretary of State administers affairs. He would have urged on the President to this unwise proceeding to gratify one of his favorites. It is a trait in his character.”5

Contemporary journalist Donn Piatt was more complimentary: “William H. Seward had all the higher qualities of statesmanship. Of a delicacy of temperament that indicated genius, he possessed a mind of rare power, which he filled with vast stores of information through patient and impartial study. His mind was singularly suggestive, and sustained by a courage industry that moulded these suggestions into measures of legislation highly beneficial to the people he served.”6 Republican journalist Henry B. Stanton later wrote that Seward “rose to the level of his responsibilities and was courageous, sagacious, sincere and earnest. He led a forlorn hope against formidable foes over which the cause he championed finally triumphed. He was grave in argument and dignified in demeanor, and though rhetorical and even ornate in style, he never indulged in those flashy flippances that sometimes succeed in palming themselves off as wit, but which legitimate wit repudiates as a bastard progeny.”7

But journalist Piatt saw a dark side in Seward’s political character. “Of refined, gentlemanly instincts and high training, he was willing to condone in others practices not for a moment to be tolerated in himself. No man for example, could denounce the sin of slavery with more power than he, and yet no Abolition leader was so intimate and popular with slave-holders.” Piatt contended that Seward subcontracted to Whig-Republican boss Thurlow Weed ‘the ruder and more vulgar features of politics corruption”…..He knew all this. Riding in the calm security of his quiet life, he heard, without seeing or being disturbed, the ugly waves beyond. Among the sober, earnest men of the Abolition faith with whom he acted he was regarded as insincere. His intimacy with and friendship for the fire-eaters of the South added to the suspicion, and his light cynical tone in treating of all topics made the hot-gospellers of the Anti-Slavery Army more than doubt him.”8 Piatt reflected the popular conception that Seward “turned over to his subordinate the work he could not do, and it proved the work that built his pedestal, and gave him the power that comes through official position.”9

New York Attorney George Templeton Strong of Seward wrote after the Cabinet crisis in December 1862: “I do not think Seward a loss to government. He is an adroit, shifty, clever politician, in whose career I have never detected the least indication of principle. He believes in majorities, and it would seem, in nothing else. He has used anti-Masonry, law reform, the common school system, and anti-slavery as means to secure votes, without possessing an honest conviction in regard to any of them.”10 But after sitting next to Seward at a Washington dinner ten months later, Strong wrote that he was “satisfied there is more of him than I supposed. He is either deep or very clever in simulating depth, and discoursed of public affairs in a statesmanlike way, as I thought.”11

Seward was a lightening rod for controversy. “Apart from politics, I liked the man, though not blind to his faults. His natural instincts were humane and progressive. He hated Slavery and all its belongings….” wrote New York Tribuneeditor Horace Greeley, a frequent antagonist.12 “He was an interesting man, of an optimistic temperament, and he probably had the most cultivated and comprehensive intellect in the administration. He was a man who was all his life in controversies, yet he was singular in this, that, though forever in fights, he had almost no personal enemies. Seward had great ability as a writer, and he had what is very rare in a lawyer, a politician, or a statesman — imagination. A fine illustration of his genius was the acquisition of Alaska. That was one of the last things that he did before he went out of office, and it demonstrated more than anything else his fixed and never-changing idea that all North America should be united under one government,” wrote Charles A. Dana, who had helped Greeley run the New York Tribune.13 Dana observed: “Mr. Seward was an admirable writer and an impressive though entirely unpretentious speaker. He stood up and talked as though he were engaged in conversation, and the effect was always great. It gave the impression of a man deliberating ‘out loud’ with himself.”14

Seward had his admirers. Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “From the day of his governorship to his death Seward was the great hero of the foreign-born — a fact that caused one part of the population to regard him as the most enlightened of statesmen and another to assail him as a demagogue who was betraying American institutions to advance his political fortunes.”15

However, Seward biographer Frederic Bancroft observed: “Many Republicans of Know-Nothing antecedents disliked Seward for his opposition to them in former years, and said that almost any other candidate would be more acceptable. Conservative Republicans also objected that the scattered remnants of the Whig party, especially in the border states of both sections, still regarded him as the exponent of the ‘higher law’ and the ‘irrepressible conflict,’ for they did not consider his latest speech altogether conclusive, and were inclined to believe, as Thaddeus Stevens had said in the House, ‘Those candidates for the presidency will go for any bill.'” according to Seward biographer Frederic Bancroft. “The fact that Seward had been prominent so long; that for a decade he had had no rival in the opinion of the progressive people of the North; that he had been in perfect harmony with the changing tendencies, first of the best Whigs and then of the best Republicans — these furnished opportunities for dangerous attacks upon him.”16

Resentment of Seward’s power and dismissal of his virtues spanned political parties. Biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “Many of Seward’s critics — radical abolitionists, conservative Republicans, and Democrats — declared him to be merely a time-serving, clever, ambitious seeker after power and place. There was an element of truth in this contention. His posturing in the Senate, his use of what Greeley called dexterity in statesmanship, his veering from universal conciliation to bitter condemnation of the southern slaveholders, gave color to his enemies’ attacks. But a close examination of his views as mirrored in his senatorial career shows that he possessed certain fundamental convictions which he strove to translate into action; that the man who put on his table service the motto Esse quam videre — To be rather than to seem — had a vision of the good society that transcended any desire for power and place. It would be too much to say that he sought political advancement solely for the purpose of serving his country’s welfare. It is, nevertheless, true that his conception of what his country was, and what it should become, formed a basis for much of his thought and action during the national period of his career.”17

No doubt that Seward could be as charming as he could be abrupt. “One of Seward’s most notable qualities was his genius for disarming hostility, and he exercised this gift strenuously in the maintenance of the most varied friendships,” wrote historian David M. Potter. He had successfully charmed even declared enemies, and with his ostensible allies in the new party he took every pains to establish good feeling. Making up in zeal what he had lacked in promptness in coming to the standard, he indulged in extreme anti-slavery utterances by means of which he soon established among the Republicans the same ascendancy he had enjoyed as a Whig.”18

Historian Potter wrote: “Seward had been the leader of the Republican Party, and especially of the Republicans in Congress, for nearly six years. He held this pre-eminence by qualities which peculiarly fitted him for a position of influence in a parliamentary body. Though he lacked the erudition and grandiose pedantry of Charles Sumner, he was probably the most intelligent member on the Republican side of the Senate. Keen insight, balanced judgment, and a capacity for thinking in broad terms characterized his mind. Moreover, his intellect was free from the rigid moral dogmatism which hardened the mental arteries of many anti-slavery men. Because of this, he was quick to sense the trend of events and to alter his own course according to circumstances. This quality may be regarded as tactical skill or as conscienceless opportunism, but it made him, in either case, a dangerous antagonist, for he strove only for objectives which he might hope to win. The moral grandeur of ‘lost causes’ held little appeal for him. Consequently he became a superb politician, a master of artifice, equivocation, and silence. His lack of moral fervor made it possible for him to maintain an astonishing diversity of friends — ranging from Jefferson Davis to Theodore Parker. And, when applied to himself, his detachment of mind left him free from senatorial pomposity. This did not mean that he lacked self-confidence; on the contrary, he sometimes magnified his own role. But the cynical vein in his nature took an introspective turn, and left him without any touch of the ex cathedra attitude.”19

Biographer Van Deusen noted that Seward was a “voracious reader” and had “a mind crammed with information gleaned from the literature of Europe and America, and from a host of American contemporaries ranging from Washington Irving to Jean Louise Rodolphe Agassiz. He had a remarkable ability to organize information, and he unquestionably possessed imaginative power, a breadth of view, a knowledge of human nature, and a capacity for logical argument that, combined with fertility of expression, marked him as a man of outstanding intellectual capacity.”20

Historian Potter also observed: “Seward’s chagrin at the [1860] nomination of Lincoln had been deep, and for a time he was ‘content to quit with the political world, when it proposes to quit with me.’ It cost him a great psychological effort to face his senatorial associates after his defeat, and for a time he seemed eager to escape every responsibility and every act which would require him to assume a position of leadership. This heartsickness found expression in a letter to Mrs. Seward: ‘I have not shrunk from any fiery trial prepared for me by the enemies of my cause. But I shall not hold myself bound to try, a second time, the magnanimity of its friends. During the campaign, Seward imposed upon himself the discipline of a speaking tour, and as time healed his wounds, he recovered his zest for politics. But as late as November 18, he declared, ‘I am without schemes, or plans, hopes, desires, or fears for the future that need trouble anybody, so far as I am concerned.’ While this mood endured, Republican senators could not look to their New York colleague for his customary leadership.”21

Mr. Lincoln had first met Seward on campaign trail in Massachusetts. They both spoke at the Tremont Temple in Boston on September 22, 1848. “We can only conjecture the effect of Seward’s method and manner on the speaking of Lincoln; but when we again listen to him on the stump, we find him making speeches so unlike those of the party-politician phase of his life now drawing to a close, that another and entirely different man seems to be delivering them,” wrote Lincoln biographer Albert J. Beveridge. “Next day Lincoln said to Seward: ‘I have been thinking about what you said in your speech. I reckon you are right. We have got to deal with this slavery question, and got to give much more attention to it hereafter than we have been doing.’ One of the greatest qualities of Lincoln, if, indeed, not the very greatest, was his eagerness to learn, his capacity to grow.”22

The twists and turns of Seward’s actions alienated many Republicans. “Above all, he was an improviser. His whole genius, backed by irresistible personal force, was for meeting practical situations with some rapidly devised measure, taking little thought of ultimate consequences, and trusting to the country’s growth for remedying all defects.” wrote historian Allan Nevins.23 On October 25, 1858, Seward had delivered a controversial “irrepressible conflict” speech in Rochester:

Our country is a theater which exhibits in full operation two radically different political systems: the one resting on the basis of servile labor, the other on the basis of voluntary labor of free men…Hitherto the two systems have existed in different States, but side by side within the American Union. This has happened because the Union is a confederation of States. But in another aspect the United States constitute only one nation. Increase of population, which is filling the States out of their very borders, together with a new and extended network of railroads and other avenues, and an internal commerce which daily becomes more intimate, is rapidly bringing the States into a higher and more perfect social unity or consolidation. Thus, these antagonistic systems are continually coming into closer contact, and collision results.

Shall I tell you what this collision means? They who think that it is accidental, unnecessary, the work of interested or fanatical agitators, and therefore ephemeral, mistake the case altogether. It is an irrepressible conflict between opposing and enduring forces, and it means that the United States must and will, sooner or later, become either entirely a slave-holding nation or entirely a free-labor nation. Either the cotton and rice fields of South Carolina, and the sugar plantations of Louisiana, will ultimately be tilled by free-labor, and Charleston and New Orleans become marts for legitimate merchandise alone, or else the rye fields and wheat fields of Massachusetts and New York, must again be surrendered by the farmers to slave culture and to the production of slaves, and Boston and New York become once more markets for the trade in the bodies and souls of men.24

After the “irrepressible conflict” speech in 1858, according to Nevins, “Having blown too hot, he tried to blow too cold. The inconsistency revealed Seward’s greatest weakness, his want of any compelling sense of principle. He would take advanced and even reckless positions with an air of Hotspur courage, but he lacked the profound convictions of Lincoln and Sumner, Jefferson Davis and Stephens. His partial retraction did not mitigate the shock of his Rochester blast.”25 Nevins wrote critically of Seward, saying, he “lacked the cardinal requisite of steady judgement: “His ‘higher law’ speech in 1850 was not only poor politics but bad statesmanship, and the ‘irrepressible conflict’ address of 1858 was still more unfortunate…Save in devotion to the Union, he seemed to lack constancy.”26 Seward occasionally spoke in absolutes. In a 1854 speech, for example, Seward talked about the “eternal struggle between conservatism and progress, between truth and error, between right and wrong.”27 Chauncey M. Depew later wrote more charitably of his Republican colleague and the rhetorical flourishes which got him into political trouble:

In the career of a statesman a phrase will often make or unmake his future. In the height of the slavery excitement and while the enforcement of the fugitive slave law was arousing the greatest indignation in the North, Mr. Seward delivered a speech at Rochester, N. Y., which stirred the country. In that speech, while paying due deference to the Constitution and the laws, he very solemnly declared that “there is a higher law.” Mr. Seward sometimes called attention to his position by an oracular utterance which he left the people to interpret. This phrase, “the higher law,” became of first class importance, both in Congress, in the press, and on the platform. On the one side, it was denounced as treason and anarchy. On the other side, it was the call of conscience and of the New Testament’s teaching of the rights of man. It was one of the causes of his defeat for the presidency.28

Seward avoided the 1856 presidential campaign rather become the Republican Party’s first candidate and first loser. Instead, he bided his time and as the 1860 election neared, he began to moderate his rhetoric. With the aid of Thurlow Weed, Seward positioned himself as the presumptive Republican candidate for President, but he failed even to unify the New York State Republican party. “Vigorous and able men were working in opposition to Seward’s candidacy, some openly and others beneath the surface. Greeley, who was highly regarded in the West and in New England, actively sought his defeat. Other important New Yorkers, including James S. Wadsworth and David Dudley Field, who remembered that the Dictator [Thurlow Weed] had overlooked their own aspirations when Preston King was selected for the Senate three years earlier and William Cullen Bryant, who resented the intimacy between Seward and ‘Boss’ Weed, strongly supported Lincoln,” wrote David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman in A History of New York State.29

Confident in his ultimate victory Seward remained at his home in Auburn during the Republican convention in mid-May — while Thurlow Weed directed his political operations in Chicago. The messages Seward received from supporters in Chicago were positive. “All right. Every thing indicates your nomination today sure,” read one telegram on the eve of the presidential vote.30 Seward biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “Seward’s friends thereupon moved a cannon, probably the brass six-pounder, to a street close by the Seward home. The plan was that when the good news came, the gun would be placed in the little park adjoining the Seward grounds and fired in celebration.”31 Their optimism was dashed when a telegram was received from Governor Edwin M. Morgan: “Lincoln nominated third ballot.” Seward responded to the news by telling gathered friends: “Well, Mr. Lincoln will be elected and has some of the qualities to make a good President.”32

According to biographer Frederic Bancroft, “Within a few hours after Lincoln’s success became known, several of Seward’s closest Republican friends were gathered as guests at his house. He told them that he would not attempt to conceal his disappointment; that the nomination of Lincoln would be the best thing for the country, for Lincoln could command the strength of the Northwest for use against any danger. He concluded by requesting those present to suppress all expressions of personal grief and to give Lincoln their hearty support. He expressed similar sentiments three days later in a letter to the Republican central committee of New York city, and in addition disclaimed all responsibility for his late candidacy.”33 Seward himself wrote: “Let the watchword of the Republican party be ‘Union and Liberty,’ and onward to victory.”34

But, privately, Seward was crushed by his unexpected defeat. He wrote Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner: “True! what would have been for me that which I am supposed to have lost! The gratification of the pride and sympathy of friends. What for me is the disappointment? The sorrow of friends not all at once to be consoled. I should have been unworthy of them and they unworthy of me had it been otherwise.”35 A year later, Secretary of State Seward was discussing the appointment of Carl Schurz to a European diplomatic post with Wisconsin Congressman John Potter. Potter explained that Wisconsin Republicans would be disappointed if Schurz were not appointed. Seward reportedly “jumped up from his chair, paced the floor excitedly, and exclaimed: ‘Disappointment! You speak to me of disappointment. To me, who was justly entitled to the Republican nomination for the presidency, and who had to stand aside and see it given to a little Illinois lawyer! You speak to me of disappointment!'”36

Although Seward returned to the Senate, he also determined to retire at the end of his term in March 1861. In late August 1860, however, Seward took to the campaign trail — speaking in the Northwest against the extension of slavery and for the candidacy of President Lincoln. At the end of the trip, wrote biographer Glyndon Van Deusen, “the train on which Seward rode made a twenty-minute stop on October 1 in Springfield, and Lincoln came aboard. Young Charles Francis Adams noted the awkward manner of the Republican nominee, noticed too, that Seward seemed constrained in manner. Lincoln suggested a point that he would like Seward to make in his speech at Chicago on October 3, and Seward said that he would do so. Seward wrote later that he had followed the suggestion but the newspapers had reported it rather briefly.”37

Mr. Lincoln easily carried New York on Election Day and quickly determined to offer Seward the position of Secretary of State. Future Attorney General Edward Bates visited Mr. Lincoln in Springfield on December 16 and recorded in his diary that the President-elect “did not attempt to disguise the difficulties in the way of forming a Cabinet, so as at once to be satisfactory to himself, acceptable to his party, and not specially offensive to the more conservative of his party adversaries. He is troubled about Mr. Seward; feeling that he is under moral, or at least party, duress, to tender to Mr. S.[eward] the first place in the Cabinet. By position he seems to be entitled to it, and if refused, that would excite bad feeling, and lead to a dangerous if not fatal rupture of the party. And the actual appointment of Mr. S.[eward] to be secretary of State would be dangerous in two ways — 1. It would exasperate the feelings of the South, and make conciliation impossible, because they consider Mr. S.[eward] the embodiment of all that they hold odious in the Republican party — and 2. That it would alarm and dissatisfy that large section of the Party which opposed Mr. S[eward]’s nomination, and now think that they have reason to fear that, if armed with the powers of that high place, he would treat them as enemies. Either the one or the other of these would tend greatly to weaken the Administration.”38

Two weeks later, Bates was again summoned to Springfield. He recorded in his diary on December 31: “I knew that Mr. L. felt himself under a sort of necessity to offer Mr. Seward the State Department, and suppose that he did it in the hope that Mr. S[eward] wd. decline. But Mr. S.[eward] in a brief note says that after consultation with and advice of friends, he accepts.”39

Ironically, rather than alienating the South, Senator Seward was trying hard to try to conciliate it.

“Seward, more than anyone else, held the center of attention when Congress met. Lincoln, who might have received greater public notice, was clinging scrupulously to his position as a private citizen, not yet formally elected, much less inducted, as President. With Lincoln silent in Springfield, the public gaze turned upon Seward, the leader in Congress, and, as rumor had it, the next Secretary of State,” wrote historian David M. Potter. “Had Seward been prepared to act vigorously at this juncture, he might have exerted an enormous influence. Certainly he would have had all the advantage which a decisive man always enjoys in dealing with those who are bewildered. But he was, himself, inhibited at this critical moment by his reticence in assuming leadership so soon after his defeat for the nomination, by his underestimate of the crisis, and by his anxiety not to take any step that would impair his prospective influence with the new administration.”40

Seward’s leadership was complicated by the positions being taken by Thurlow Weed. According to historian Jeter Allen Isely, “Following Lincoln’s success in November, Weed began publishing conciliatory editorials in his Albany Evening Journal, and the Tribune staff was convinced that Seward had inspired if not written these articles. This conclusion was given credence by Seward’s stand in the congress which was to expire with Lincoln’s inaugural. Overnight the New York senator ceased to be known as a firebrand radical and was recognized [as] a compromising conservative. Both he and Weed appeared anxious to sustain the essential outlines of [Kentucky Senator John] Crittenden’s proposal. It now seems evident that Seward was playing for time in which to bring border state unionism to the surface.”41

According to historian Potter, Seward “would have had difficult in getting clear of the Evening Journal proposal, and in this case the task was made more difficult, so Seward believed, by the deliberate misrepresentations which emanated from the unfriendly Tribune office. There certain Republican congressmen visited while en route to Washington, and there Charles A. Dana assured them that the voice was the voice of Seward, even though the hand was the hand of Weed — that Weed had merely penned the editorials, while Seward had actively inspired them because he ‘wanted to make a great compromise like Clay and Webster.'”42 Seward was subsequently interrogated by other Republican senators about the Weed proposals. Seward himself complained to his wife that “Mr. Weed’s articles have brought perplexities about me which he, with all his astuteness, did not foresee.”43

Historian Van Deusen wrote: “Busily revolving in his mind ideas for saving the Union ‘without sacrifice of principle,’ Seward found Weed’s action well-intentioned but impulsive and embarrassing, and he made this clear to Weed. He, himself, felt compromise was not the answer; and that any constitutional amendment satisfactory to the South could not pass Congress. He believed that South Carolina and the Deep South would go out of the Union, but that then passion would be succeeded by perplexity about whether to conciliate the Union or fight it. The best policy, he felt sure, was one of moderation, kindness, and reticence, in order to reconcile southerners to the incoming administration.”44

Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “William H. Seward had not fully accepted his eclipse as leader of the Republican party by Lincoln’s nomination and election as president. Seward not only aspired to be the ‘premier’ of the Lincoln administration; he also emerged as the foremost Republican advocate of conciliation toward the South during the secession winter.” McPherson wrote: “But in January 1861 he wrote to Lincoln that ‘every thought that we think ought to be conciliatory, forbearing and patient’ toward the South. Lincoln was willing to go along partway with this advice. But Seward flirted with the idea of supporting the Crittenden Compromise, whose centerpiece was an extension of the Missouri Compromise line of 36 30′ between slavery and freedom to all present and future territories. This would have been a repudiation of the platform on which the Republicans had stood from the beginning, and on which they had just won the election.”45

Historian George H. Mayer wrote: “A larger Republican plan began to unfold in January under the skillful direction of Seward. Its over-all objective was to freeze the status quo until Lincoln’s inauguration by encouraging every kind of activity that would prolong negotiations. Good intentions lay behind Seward’s hypocritical formula of conciliatory talk and no action. He believed that citizens of the Gulf states were victims of a blind, unreasoning panic and would clamor for readmission as soon as the Republican Administration demonstrated its good will toward the South. Seward also thought it was mandatory to conciliate the upper South while waiting for the Union reaction to develop in the Gulf states.”46

President-elect Lincoln thought it more important to conciliate Seward than to conciliate the South. On January 12, 1861, President-elect Lincoln wrote Seward: “Your selection for the State Department having become public, I am happy to find scarcely any objection to it. I shall have trouble with every other Northern cabinet appointment—so much so that I shall have to defer them as long as possible, to avoid being teased to insanity to make changes.47But there was objection — even in New York State. Seward’s association with Weed was hurting him. Weed’s fellow editors, including the Tribune‘s Horace Greeley and the Evening Post‘s William Cullen Bryant, lobbied Mr. Lincoln against Seward’s Cabinet nomination. Historian David Potter argued that Seward’s interest in the Cabinet post, sensitivity to opposition and unwillingness to embarrass President-elect Lincoln limited his ability to advocate compromise in the North-South crisis.48

Seward saw himself as central to any possibility of compromise and concession with the South. On January 12, Seward delivered a long-awaited speech on the crisis. Speaking of secession, Seward said: “If others shall invoke that form of action to oppose and overthrow government, they shall not, so far as it depends on me, have the excuse that I obstinately left myself to be misunderstood. In such a case I can afford to meet prejudice with conciliation, exaction with concession which surrenders no principle, and violence with the right hand of peace.”49 He said: “We are in fact, a homogeneous people, chiefly of one stock, with accessions well assimilated. We have, practically, only one language, one religion, one system of Government, and manners and customs common to all. Why, then, shall we not remain henceforth, as hitherto, one people?”50

Seward concluded: “Soon enough, I trust, for safety, it will be seen that sedition and violence are only local and temporary, and that loyalty and affection to the Union are the natural sentiments of the whole country. Whatever dangers there shall be, there will be the determination to meet them; whatever sacrifices, private or public, shall be needful for the Union, they will be made. I feel sure that the hour has not come for this great nation to fall….This Union has not yet accomplished what good for mankind was manifestly designed by Him who appoints the seasons and prescribes the duties of states and empires…..It is the only government that can stand here. Woe! Woe! To the man that madly lifts his hand against it. It shall continue and endure; and men, in after times, shall declare that this generation, which saved the Union from such sudden and unlooked-for dangers, surpassed in magnanimity even that one which laid its foundations in the eternal principles of liberty, justice, and humanity.”51 Biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “It was a moving speech, and at times during its delivery more than one Senator bowed his head and wept. But it was susceptible to a wide range of interpretation. Some thought that it offered real concessions to the South, and [wife] Frances wrote in sorrow that its ‘compromises,’ as she called them, put Henry ‘in danger of taking the path which led Daniel Webster to an unhonored grave ten years ago.’ New York merchants praised its concessions, and border state congressmen were pleased, though not ecstatic.”52

The speech had its admirers — but not among abolitionist Republicans who found it too soft. As Gideon Welles later wrote, Seward had “advanced a policy diametrically opposed to emancipation by the general Government. ‘I am willing,’ said he on that occasion, ‘to vote for an amendment to the Constitution declaring that it shall not by any future amendment be so altered as to confer on Congress a power to abolish or interfere with Slavery in any State.'”53 But, noted biographer Frederic Bancroft: “Considering the actual conditions and what was most urgent at that time, there is reason to believe that this was as wise, as patriotic, and as important a speech as has ever been delivered within the walls of the Capitol. If Seward had spoken as most of the Republicans had done, or if he had gone no farther than Lincoln had even confidentially expressed a willingness to go, by March 4th there would have been no Union that any one could have summoned sufficient force to save or to re-establish.”54

“All during late January and February, Seward continued his policy of playing for time, while he strove to damp the desires and stifle the impulses of ultras, both North and South,” wrote biographer Glyndon Van Deusen.55 Seward wrote President Lincoln on January 27

The appeals from the Union men in the Border states for something of concession or compromise are very painful since they say that without it those states must all go with the tide, and your administration must begin with the free states, meeting all the Southern states in a hostile confederacy. Chance might render the separation perpetual. Disunion has been contemplated and discussed so long there that they have become frightfully familiar with it, and even such men as Mr Scott and William C. Rives are so far disunionists as to think that they would have the right and be wise in going if we will not execute new guaranties which would be abhorent [sic] in the North.

It is almost in vain that I tell them to wait, let us have a truce on slavery, put our issue on Disunion and seek remedies for ultimate griefs in a constitutional question.

This is the dark side of the picture. Now for the brighter one. Beyond a peradventure disunion is falling and Union rising in the popular mind Our friends say we are safe in Maryland and Mr Scott and others tell me that Union is growing rabidly as an element in Virginia

In any case you are to meet a hostile armed confederacy when you commence. You must reduce it by force or conciliation The resort to force would very soon be denounced by the North, although so many are anxious for a fray. The North will not consent to a long civil war A large portion, much the largest portion of the Republican party are reckless now of the crisis before us and compromise or concession though as a means of averting dissolution is intolerable to them. They believe that either it will not come at all, or be less disastrous than I think it will be For my own part I think that we must collect the revenues regain the forts in the gulf and, if need be maintain ourselves here But that every thought that we think ought to be conciliatory forbearing and patient, and so open the way for the rising of a Union Party in the seceding states which will bring them back into the Union-

It will be very important that your Inaugural address be wise and winning.

I am glad that you have suspended making Cabinet appointments[.] The temper of your administration whether generous and hopeful of Union, or harsh and reckless will probably determine the fate of our country.

May God give you wisdom for the great trial & responsibility56

Biographer Glyndon Van Deusen offered an upbeat analysis of the New York Senator’s maneuvers: “Seward talked too much, especially when exhilarated by wine or brandy, and sometimes the ideas he threw out bred suspicion as to his designs. It is also true that he greatly underestimated the force and stamina of the secession movement. But it is equally certain that his ‘bridge-building, as he called it, played a significant part in keeping Virginia and the other border slave states in the Union during those critical months.”57

Seward’s actions during this period can either be construed as those of a patriotic Machiavelli or a Machiavellian appeaser. Mr. Lincoln, though much less inclined to compromise than Seward, seemed to accept Seward’s devious ways. Seward was a master of intrigue — his positions and relationships in early 1861 were strange — which apparently represented his attempt to forestall the inevitable. Seward seemed unreliable to those valued principle. “It is difficult to evaluate the voluble Seward’s contribution during this critical period,” wrote historian George H. Mayer. “One thing was certain: his policy had a demoralizing effect on the Republican party. At the time, many people thought the party would disintegrate, but Seward had no doubt about the verdict of history. ‘I have brought the ship off the sands,’ he wrote his wife on the eve of Lincoln’s inauguration, ‘and am ready to resign the helm into the hands of the captain whom the people have chosen.'”58

The masterpiece of intrigue was submitted by Secretary of State Seward to the President on April 1, 1861. “Probably in consultation with Weed (who was in Washington toward the end of March), he outlined a proposal to put before the President. Raymond, summoned to Washington for a midnight conference at Seward’s home, pledged his support if Lincoln accepted the plan. Then, on March 30, in what must have seemed a providential manner, the news broke that Spain had annexed San Domingo and by arrangement with France was about to take over Haiti as well. The next day was Sunday, and that afternoon Seward wrote out the draft of a paper entitled ‘Thoughts for the President’s Consideration.’ Frederick copied it, giving it the date of April 1, and on the morning of that day delivered it to Lincoln,” wrote historian Glyndon Van Deusen.

Seward’s memorandum was a masterpiece of political usurpation which suggested that the Administration that a policy and perhaps a foreign war with France and Spain would give it one and unite the divided country at the same time. In order to implement the needed policy, someone was needed to take charge — with the inference that Seward was ready to take that position. President Lincoln diplomatically rejected both the premises of Seward’s presumptuous memo and the political solutions he proposed as well.

In his diary, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles returned repeatedly to the interferences, secretiveness, and incompetence of the Secretary of State. In September 1862, Welles wrote that Seward “is anxious to direct, to be the Premier, the real Executive, and give away national rights as a favor. Since our first conflict, however, when he secretly interfered with the Sumter expedition and got up an enterprise to Pensacola, we have no similar encounter; yet there has been an itching propensity on his part to have a controlling voice in naval matters with which he has no business, — which he really does not understand, — and he sometimes improperly interferes as in the disposition of mails on captured vessels.”59

In April 1863, Welles wrote that “while Mr. Seward has talents and genius, he has not the profound knowledge nor the solid sense, correct views and unswerving right intentions of the President”.60 Seward’s intentions were seldom clear. It was a virtual policy for him to be enigmatic. Attorney General Edward Bates complained in his diary in July 1864 that Seward was avoiding his request for a meeting on political affairs: “More than three weeks have passed, and I have not heard from him. I asked for that meeting chiefly because Mr. S. as it seemed to me, carefully concealed his views of the gravest public questions from me. I noted that, even in C.[abinet] C.[ouncil] when I was present, whenever declared his principles and measures in a straight-forward manly way, but dealt in hints and suggestions only, as if to keep open all availab[l]e subterfuges, for future use. And, now, he declines the direct request of a conversation. Of course, he has a reason for declining — I think it is one of two — Either he has contempt for my knowledge and ability in such matters, or he is afraid to talk with me freely, lest I find out more surely, his hollow foundations and equivocal policy.”61

After a Cabinet crisis over the reappointment of George B. McClellan to lead the Army of the Potomac in early September 1862, Welles wrote: “Between Seward and Chase there was perpetual rivalry and mutual but courtly distrust. Each was ambitious. Both had capacity. Seward was supple and dextrous; Chase was clumsy and strong. Seward made constant mistakes, but recovered with a facility that was wonderful and almost always without injury to himself; Chase committed fewer blunders, but persevered in them when made, often to his own serious detriment. In the fevered condition of public opinion, the aims and policies of the [two] were strongly developed. Seward, who had sustained McClellan and came to possess, more than any one else in the Cabinet, his confidence, finally yielded to Stanton’s vehement demands and acquiesced in his sacrifice. Chase, from an original friend and self-constituted patron of McC., became disgusted, alienated, an implacable enemy, denouncing McClellan as a coward and military imbecile. In all this he was stimulated by Stanton, and the victim of Seward, who first supplanted him with McC. And then gave up McC. to appease Stanton and public opinion.”62

Gideon Welles often complained in his diary about Seward’s influence on Mr. Lincoln. The Navy Secretary wrote in mid-August 1864: “Both [Montgomery] Blair and myself concurred in regret that the President should consult only Seward in so important a matter, and that he should dabble with Greeley, Saunders, and company. But Blair expresses to me confidence that the President is approaching the period when he will cast off Seward as he has done Chase. I doubt it. That he may relieve himself of Stanton is possible, though I see as yet no evidence of it. To me it is clear that the two S.’s have an understanding, and yet I think each is wary of the other while there is a common purpose to influence the President. The President listens and often defers to Seward, who is ever present and companionable. Stanton makes himself convenient, and is not only tolerated but, it appears to me, is really liked as a convenience.63

Seward created some of his own troubles through injudicious statements and publications. By December 1862 the Secretary of State had become the target of intrigue from Republican Senators who blamed him for the policy failures and military defeats of the Administration. The Republican caucus first met on December 16. Historian Allan Bogue noted: “Although more moderate members of the caucus tried to temporize, the best they could do was suggest that a fact-finding deputation be sent to the president and win an adjournment before a vote was taken on the motion of want of confidence that James W. Grimes (R.,Ia.) proposed. On the next day the senators backed away from the suggestion that the president be asked to resign and instead approved Ira Harris’s (R., N.Y.) resolution ‘declaring…that a reconstruction of the cabinet would give renewed confidence in the administration’ and [Charles] Sumner’s recommendation that a committee of seven ‘call on the president and represent to him the necessity of a change in men and measures.’ Of those present, only Seward’s good friend Preston King (R., N.Y.) failed to vote for both resolutions.”64 The Senators prepared a memorandum for the President:

1st The only course of sustaining this government, preserving the national existence & restoring & perpetuating the national integrity is, by a vigorous & successful prosecution of the war; the same being a patriotic & just war on the part of this nation, produced by & rendered necessary to suppress, a causeless & atrocious rebellion.

2d The theory of our government and the early and uniform practical construction thereof, is, that the President should have be aided by a cabinet council, agreeing with him in political principles, & general policy, & that all important public measures & appointments should be the result of their combined wisdom & deliberation. This, most obviously, necessary condition of things, without which no administration can succeed, we & the public believe does not now exist, & therefore such selections & changes in its members should be made, as will secure to the country unity of purpose & action, in all material & essential respects, especially in the present crisis of public affairs.

3d That the Cabinet should be exclusively composed of statesmen, who are the cordial, resolute, unwavering supporters of the principles and purposes first above stated.

4th It is unwise & unsafe to commit the direction, conduct or execution of any important military operation or any separate general command or enterprise in this war, to any one who is not a cordial believer & supporter of the same principles & purposes so first above stated.

The Republican Senators of the United States, entertaining the most unqualified confidence in the integrity & patriotism of the President, identified, as they are, with the success of his administration, profoundly impressed with the critical condition of our national affairs & deeply convinced that the public confidence requires a practical regard to the foregoing propositions & principles, feel it their duty, from the position they occupy, respectfully to present them for executive consideration & action.65

After the caucus Senator King rushed to see Seward and explain that the Republican Senators were virtually demanding his ouster. Seward wrote out his resignation. With Seward’s son Frederick, King brought Seward’s resignation to the President: “I hereby resign the office of Secretary of State of the United States, and have the honor to request that this resignation may be immediately accepted.”66

Seward biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “Lincoln carefully felt his way toward a solution of the crisis.”67 The President met with a Senate delegation on December 18, his Cabinet on December 19 and both on the night of December 19. According to Attorney General Edward Bates, “The Prest said that he had a long conference with the [senate] Com[mitt]ee., who seemeed [sic] earnest and said — not malicious nor passionate — not denouncing any one, but all of them attributing to Mr. S.[eward] a lukewarmness in the conduct of the war, and seeming to consider him the real cause of our failures.” Bates wrote in his diary: “To use the P[r]est’s quaint language, while they believed in the Prest’s honesty, they seemed to think that when he had in him any good purposes, Mr. S.[eward] contrived to suck them out of him unperceived.”68

At the night session on December 19, Bates and Blair both defended the harmony of the Cabinet in general and Seward in particular. President Lincoln even maneuvered Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, who had maneuvered the Senators to make their mutinous moves, into defending Cabinet harmony. The next day, Chase offered his resignation. President Lincoln pocketed both Seward’s and Chase’s resignation and declared the crisis over. Ten months later, President Lincoln had a conversation with Presidential aide John Hay about how he had handled the crisis. Hay wrote in his diary:

He went on telling the history of the Senate raid on Seward — how he had & could have no adviser on that subject & must work it out by himself — how he thought deeply on the matter — & it occurred to him that the way to settle it was to force certain men to say to the SenatorsHere what they would not say elsewhere. He confronted the Senate & the Cabinet. He gave the whole history of the affair of Seward & his conduct & the assembled Cabinet listened & confirmed all he said.

“I do not now see how it could have been done better. I am sure it was right. If I had yielded to that storm & dismissed Seward the thing would all have slumped over one way & we should have been left with a scanty handful of supporters.”69

The friendship between Lincoln and Seward proved stronger than the combined weight of the Senate Republican caucus. According to Lincoln biographer Alonzo Rothschild, Seward “found safety behind the man whom, not many months before, he had thought to thrust into the background. After the repulse of the senatorial cabal, moreover, Lincoln made short work of those who came to undermine the Secretary of State. He shielded Seward against all such assaults, and kept him secure in his high office to the end.”70 Clearly, the relationship between Seward and President Lincoln had evolved. Biographer Nathaniel Wright Stephenson wrote: “During twenty months, since their clash in April, 1861, Seward and Lincoln had become friends; not merely official associates, but genuine comrades. Seward’s earlier condescension had wholly disappeared. Perhaps his new respect for Lincoln grew out of the President’s silence after Sumter. A few words revealing the strange meddling of Secretary of State would have turned upon Seward the full fury of suspicion that destroyed McClellan. But Lincoln never spoke those words. Whatever blame there was for the new failure of the Sumter expedition, he quietly accepted as his own. Seward, whatever his faults, was too large a nature, too genuinely a lover of courage, of the non-vindictive temper, not to be struck with admiration. Watching with keen eyes the unfolding of Lincoln, Seward advanced from admiration to regard. After a while he could write, ‘The President is the best of us.’ He warmed to him; he gave out the best of himself. Lincoln responded. While the other secretaries were useful, Seward became necessary.”71

Seward had a difficult job — avoiding a foreign war while protecting U.S. interests and preventing any European aid for the Confederacy. Sometimes, he had to conciliate and sometimes he had to bluff and bluster. He was a lightening rod for criticism. “Democrats, former Democrats now in the Republican ranks, most of all the radical Republicans who considered him to be soft on slavery and therefore unfit for his post — all these joined in the onslaught. It rose to its greatest heights when there were reverses in the field, which were promptly laid at his door, but the stream of obloquy also came at other times and from other quarters, eat and west. His critics accused him of being a pusillanimous compromiser at home and a war monger abroad.”72

Seward kept an eye on New York politics. John Hay recalled a visit that Seward made to President Lincoln’s office in November 1863: “He is very easy and confident now about affairs. He says N.Y. is safe for the Presidential election by a much larger majority: that the crowd that follows power have come over: that the Copperhead spirit is crushed and humbled. He says the Democrats lost their leaders when [Robert] Toombs & [Jefferson] Davis & [John] Breckenridge forsook them and went South: that their new leaders, the [Horatio] Seymours [Clement] Vallandighams & [Fernando] Woods are now whipped and routed. So that they have nothing left. The Democratic leaders are either ruined by the war or have taken the right shoot & have saved themselves from the ruin of their party by coming out on the right side.”73

In June 1864, Seward’s enemies once again intrigued to get him out of the Cabinet. Their strategy was to nominate a War Democrat from New York for Vice President — like General John A. Dix or former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson. Initially, Seward’s forces backed the renomination of Hannibal Hamlin, but according to biographer Benjamin Thomas, “as Hamlin’s hopes began to dwindle in the face of the demand for a War Democrat, the Sewardites swung their support to Johnson, who polled 200 votes on the first ballot, to Hamlin’s 150 and Dickinson’s 108.” Thomas conjectured that “it may have been a sense of obligation to Seward that induced Johnson, originally a radical, to adopt a moderate policy when he succeeded Lincoln as President.”74

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles maintained that “In the convention there was a determination to get rid of Mr. Seward, but the managers, under the contrivance of [Henry J.] Raymond, who has shrewdness, so shaped the resolution as to leave it pointless, or as not more direct against Seward than against Blair, or by others against Chase and Stanton.”75

Unlike President Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward was not averse to responding to the rhetorical needs of impromptu gatherings. On November 18, 1863, the night before the dedication of the national military cemetery at Gettysburg, Seward addressed a serenade outside the house where he was staying: “When we part to-morrow night, let us remember that we owe it to our country and to mankind that this war shall have for its conclusion the establishing of the principle of democratic government; — the simple principle that whatever party, whatever portion of the community, prevails by constitutional suffrage in an election, that party is to be respected and maintained in power, until it shall give place, on another trial and another verdict, to a different portion of the people. If you do not do this, you are drifting at once and irresistibly to the very verge of universal, cheerless, and hopeless anarchy. But with that principle this government ours — the purest, the best, the wisest, and the happiest in the world — must be, and, so far as we are concerned, practically will be, immortal.”76

On Election Day, 1864, the New York Times published a report of Seward’s pre-election speech in Auburn, where he had gone to vote: The speech focused almost exclusively on the economic impact of casting a vote: “Everyone who has any property-interest at stake in the country, should consider seriously at this time the effect of his vote in the Presidential election on the property of the nation. We Americans have become so accustomed to ‘terrible crises’ just before elections, and to awful perils threatened in view of any given action at the polls, which entirely subsided and disappeared when either candidate was chosen, that at last, when the danger has really come, we hardly recognize it. There are probably tens of thousands of Democrats at this moment, with large stakes in the country, who have a vague idea that somehow things will turn out right, even if their candidate is elected, and that they had better stick to ‘the old party.'”77

Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “Long before the convention of 1864 Seward had become one of the strongest of Lincoln’s supporters for re-election. ‘As they sat together by the fireside,’ relates Frederick W. Seward, ‘or in the carriage, the conversation between them, however it began, always drifted back to the same channel — the progress of the great national struggle. Both loved humor, and however trite the theme, Lincoln always found some quaint illustration from his frontier life, and Seward some case in point in his long public career, that gave it new light.'”78

However, at the beginning of the fall campaign, Seward gave a speech in his home town that caused trouble. “Seward made a speech at Auburn, intended by him, I have no doubt, as the key note of the campaign,” wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles. “For a man of not very compact thought, and who, plausible and serious, is often loose in his expressions, the speech is very well. In one or two respects it is not judicious and will likely be assailed.”79 Welles was right. The speech was assailed and Mr. Lincoln was forced to clarify questions about it.

Seward was accustomed to being assailed verbally. On the night of April 14, 1865, he was physically assaulted by John Wilkes Booth’s accomplice, Lewis Payne. Seward had been seriously injured on April 5 in a runaway carriage accident and was confined to bed in his home on Lafayette Square near the White House. Payne overwhelmed Seward’s son Frederick and a male nurse and then repeated stabbed the Secretary of State. Both Frederick and his father took months to recover — during which Seward’s wife Frances attempted to care for them. But her delicate constitution could not handle the strain; she was the family member who lost the struggle with death. Their beloved and precocious daughter Fanny, who witnessed the attack, died a year later. Seward himself struggled back to health, work and another four years of controversy in the Cabinet.

Seward biographer Glyndon Van Deusen observed that Seward probably understood that President Lincoln’s death had elevated the martyred leader in history’s eyes — and his diminished the stature of Mr. Lincoln’s colleagues. “The manner of the President’s demise, [John] Bigelow told Seward, had transfigured him in the eyes of mankind. [U.S. Minister to England Charles Francis] Adams confided the same opinion to his diary, adding that now Seward would never get the credit he deserved for the record of the administration. The Secretary of State himself had no doubts as to Lincoln’s place in history. He told [James Watson] Webb that it was not necessary to ask foreign governments to put on mourning for the martyred President. ‘His name is to grow greater, and that of all contemporaneous magistrates and sovereigns to grow smaller as time advances.”80

Footnotes

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 171-172 (December 31, 1860).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 36 (May 20, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 93 (August 2, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 110 (August 17, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 164 (September 30, 1864).

- Donn Piatt, Memories of the Men Who Saved the Union, p. 139.

- Henry B. Stanton, Random Recollections, p. 61.

- Donn Piatt, Memories of the Men Who Saved the Union, p. 149.

- Donn Piatt, Memories of the Men Who Saved the Union, p. 141.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 282 (December 21, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 362 (October 11, 1863).

- Horace Greeley, Recollections of a Busy Life, p. 311.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 155-156.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 156.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 19.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, .

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 198.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 25.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 81-82.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 209.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 82-83.

- Albert J. Beveridge, Abraham Lincoln: 1809-1858, Volume I, p. 476.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861, Volume I, p. 24.

- George E. Baker, editor, The Works of William H. Seward, Volume IV, p. 292.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861, Volume I, p. 411.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861, Volume I, p. 22.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 152.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 332.

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 239.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 224 (Letter from Preston King, William Evarts and Richard Blatchford to William H. Seward, May 17, 1860).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 224.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 225.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 542.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 543 (Seward, Volume II, p. 452).

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 543 (Letter from William H. Seward to Charles Sumner, May 23, 1860).

- Carl Schurz, The Autobiography of Carl Schurz, p. 171 (Abridgment by Wayne Andrews).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 233.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 164 (December 16, 1860).

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 171-172 (December 31, 1860).

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 82.

- Jeter Allen Isely, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 318.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 84.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 85 (Letter from William H. Seward to his wife, December 4, 1860).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 239.

- James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, p. 118.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 80.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 173 (Letter to William H. Seward, January. 12. 1861).

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 86.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume II, p. 14.

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 286.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume II, p. 15-16.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 245.

- Gideon Welles, “Letters of Gideon Welles”, The Magazine of History, Vol. 27, No. 1, p. 13.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume II, p. 16.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 247.

- Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William H. Seward to Abraham Lincoln, January 27, 1861).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 249.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 82-83.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 133 (September 16, 1862).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 284 (April 22, 1863).

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 387-388 (July 20, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 139 (September 16, 1862).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 112 (August 19, 1864).

- Allan G. Bogue, The Congressman’s Civil War, p. 126.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Republican Senators to Abraham Lincoln, December 17, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William H. Seward to Abraham Lincoln, December 16, 1862).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 345.

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 269 (December 19, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 104-105 (October 30, 1863).

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln: Master of Men: A Study in Character, p. 155.

- Nathaniel Wright Stephenson, Lincoln, p. 95.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 341.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 109 (November 8, 1863).

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 429.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 174 (October 7, 1864).

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VIII, p. 191.

- “The Momentous Day”, New York Times, November 8, 1864, (www.nytimes.com/books/98/02/15/home/lincoln-momentous.html).

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 370.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 140 (September 10, 1864).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 432-433.