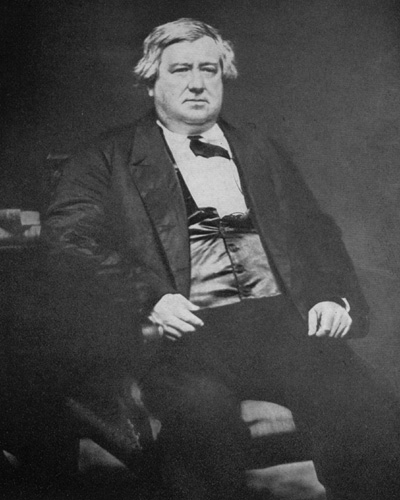

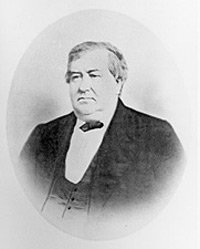

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, not one to compliment others, called Senator Preston King “a man of wonderful sagacity; has an excellent mind and judgment. Our views correspond on most questions.”1 Nearly a year after King had left the Senate in 1863, Welles wrote in his diary: “Few men in Congress are his equal for sagacity, comprehensiveness, sound judgment, and fearlessness of purpose. Such statesmen do honor to their State and country. His loss to the Senate cannot be supplied.”2 Although Senator King was well-intentioned, he was not necessarily well-mannered. He lacked certain social grace. Glyndon Van Deusen, biographer of William H. Seward, wrote: “When fat Senator Preston King fell asleep at the dinner table, or on a sofa with the ladies all around him, it was tactful [Seward daughter-in-law] Anna who gently awakened him and tried to keep the other guests from laughing at his predicament.”3

Presidential aide John Hay referred to the “ponderous bulk of the glorious old Senator Preston King.”4 King was “short and very fat,” noted historian John Niven.5 Niven wrote that King was “an experienced politician, affable, shrewd, honest and a veteran free-soiler.”6 King, was “elected to the Senate with [Thurlow] Weed’s grudging approval.” In 1859 and 1860, he was “charged with bringing the Democratic faction [of the Republican Party] behind Seward’s candidacy. Though King owed his seat more to [Horace] Greeley than to anyone else, he was eager to placate the old Whig boss. From mid-summer of 1858 until the Republican convention two years later, he would use every means at his command to persuade [Gideon] Welles and other influential ex-Democrats that Seward was the strongest candidate.”7

Historian Glyndon van Deusen noted that King’s loyalty to Secretary of State William H. Seward went back to the formation of the national Republican Party: “During the Christmas holidays in 1855, Salmon P. Chase, Francis P. Blair, Sr., Nathaniel Banks, Preston King, and others began preparations for calling a convention to meet at Pittsburgh on Washington’s birthday, 1856, and there formally launch the national Republican party. King, acting as an emissary of this group, told Seward that the plan was for a national ticket that was half Republican, half Know-Nothing, and that they wanted him in on the movement. He refused to participate, saying that he was emphatically against any combination with Know-Nothings or Know-Nothing candidates.”8

President Lincoln “had probably had no more loyal and devoted friend in the Senate than Preston King,” wrote New York Evening Post editor John Bigelow, himself part of the anti-Weed, anti-Seward faction. But Bigelow wrote in his diary in the summer of 1861 that King thought that President Lincoln left the impression that “he was not only unequal to the present crisis, but to the position he now holds at any time.” King told Bigelow that President-elect Lincoln and Vice President-elect Hannibal Hamlin had tried to use King as a go-between to Seward during the presidential transition. Bigelow wrote in his diary: “He told [Hannibal] Hamlin that the President had better ask Seward directly for the information he sought, for he felt that he was not the proper person to undertake such an embassy. Such was about the substance though not the precise words which King used. They were accompanied by a suggestive laugh which to those who knew King always meant more than his words.”9 Senator King had served two periods in the House of Representatives (1843-1847) and 1849-1853) — just before and just after Mr. Lincoln did. He won election to the U.S. Senate in 1857 — serving until 1863 when he was replaced in the Senate by Governor Edwin D. Morgan.

After William H. Seward failed to win the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, King came close to winning the vice presidential nomination himself. “The successful Illinois managers, before the convention adjourned for dinner had decided that New York should have the privilege of naming the candidate. It did not take a very discerning politician to recognize that Seward and his crestfallen friends ought to be placated. Nor was it an especially astute conclusion that if possible the candidate ought to be an Easterner, a former Democrat, and a man acceptable to the New York Senator,” wrote historian John Niven. “Preston King was the obvious choice. No northern Democrat and few Whigs — Joshua Giddings being a notable exception — had such a distinguished antislavery record. King, not [David] Wilmot, was the nimble parliamentarian who, perceptively and with the best of good humor, had attached the Wilmot Proviso to whatever legislation would ensure a maximum of debate during the late 1840’s. But King, no doubt remembering Silas Wright’s refusal of second place in 1844, would not accept. At the caucus of delegation chairman held during the dinner recess, William Evarts declined in positive terms for New York.10

After Mr. Lincoln received the Republican presidential nomination, King worked hard for his election. “The Congressional [Campaign] Committee under President King, with John Covode as treasurer, did as good work as the National Committee,” wrote historian Allan Nevins.11 King also used his influence on behalf of fellow ex-Democrat Gideon Welles. According to Welles, King “was most earnest and emphatic in favor of my [Cabinet] appointment and was sleepless and unremitting in thwarting and defeating the intrigues of Weed and others against me.”12 King also bucked the Seward faction in protesting the selection of Simon Cameron for the Cabinet.13 King wrote President-elect Lincoln in early January 1861:

I write to you with some diffidence but my earnest desire for the success of your administration and the principles upon which it was elected will I trust be my sufficient apology[.] I had seen in the papers and heard the reports that Mr. Cameron of Pennsylvania was to be a member of your cabinet though not from him as I had not had any conversation with him on the subject except on one occasion when he was in this city in August or September last. He then said in a conversation respecting the affairs of Pennsylvania that he had no thought or desire to be a member of the Cabinet if as we supposed the Republicans should be successful in the Election[.] I enquired of him yesterday respecting the reports pro and con as to his becoming a member of the Cabinet and in a free conversation he stated to me what has passed between you & him and that a friend of his upon his authority had telegraphed to you his concurrence in your last communication and that he was not to go into your Cabinet I stated to him that the object of my desiring to talk with him on the subject was to advise him to decline any proposition to go into the Cabinet of course it was not necessary to repeat it[.]

We heard here that Mr. Seward Mr. Bates and Mr. Welles are already settled upon. They are certainly good appointments[.] We have heard also that Mr. Chase is spoken of for the Treasury He is an able and good man And we have also heard many other good names spoken of for other places in the Cabinet I think it best and safest unless, you personally know your men well and I therefore suggest that you defer definitely to determine further than you may have already done upon your Cabinet until you come to Washington and have an opportunity to know the opinions of men who are reluctant to volunteer advice respecting the character and fitness of men and their localities of whom you may be thinking and I would advise that you come here as early as the middle of February I have no apprehensions of violence or disturbance of the peace here although we hear many reports of that kind and cannot speak with certainty because of the secret societies and darkness in which treasonable conspiracies act. Watchfulness is undoubtedly proper and any day facts or movements not now known or apprehended may be developed-14

King was far less willing to compromise with the South than was Seward — writing to Thurlow Weed in December 1860: “You and Seward should be among the foremost to brandish the lance and shout for war.”15 King was also more supportive of emancipation that Seward, writing President Lincoln after he had issued the draft Emancipation Proclamation in September 1860: “You have made me very glad to day in reading your Proclamation which reached here this morning”.16

Despite his differences with Seward, King remained loyal to the Secretary of State in a crucial confrontation with Seward’s enemies after the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. The New York Senator played a pivotal role at the Republican caucus on December 17 that sought a major overhaul in President Lincoln’s cabinet. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “For a few minutes it seemed that the Senate and President were about to be brought into direct collision. But Preston King of New York and others protested against [Senator James W. ] Grimes’s proposal, and several members agreed with Orville H. Browning that the best course would be to send a deputation to call on the President, learn the true state of affairs, and give him a frank statement of their opinions.”17 After the meeting, King went to the home of Secretary of State Seward to warn him that his colleagues were after Seward’s head. Seward wrote out his resignation and sent it to the White House with King and Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward.

When Senator King and Seward’s son arrived at the White House, wrote historian Allan Nevins, “Lincoln, astounded at his dinner hour by the sudden resignations, turned to the portly New York Senator to demand an explanation. When King told him about the caucus action, his perplexity increased. Later that evening the dismayed President went to Seward’s house to get him to withdraw his resignation, but all arguments were in vain — Seward would not budge.”18 To Seward’s desire to resign, Mr. Lincoln said: “Ah, yes, Governor, that will do very well for you, but I am like the starling in Sterne’s story, ‘I can’t get out.'”19 Navy Secretary Gideon Welles reported what he was told a Cabinet meeting on December 19:

The President desired that what he had to communicate should not be the subject of conversation elsewhere, and proceeded to inform us that on Wednesday evening, about six o’clock, Senator Preston King and F.W. Seward came into his room, each bearing a communication. That which Mr. King presented was the resignation of the Secretary of State, and Mr. F. W. Seward handed in his own. Mr. King then informed the President that at a Republican caucus held that day a pointed and positive opposition had shown itself against the Secretary of State, which terminated in a unanimous expression, with one exception, against him and a wish for his removal. The feeding finally shaped itself into resolutions of a general character, and the appointment of a committee of nine to bear them to the President, and to communicate to him the sentiment of the Republican Senators. Mr. King, the former colleague and the personal friend of Mr. Seward, being also from the same State, felt it to be a duty to inform the Secretary at once of what had occurred. On receiving this information, which was wholly a surprise, Mr. Seward immediately wrote, and by Mr. King tendered his resignation. Mr. King suggested it would be well for the committee to wait upon the President at an early moment, and, the Secretary agreeing with him, Mr. King on Wednesday morning notified Judge [Jacob] Collamer, the chairman, who sent word to the President that they would call at the Executive Mansion at any hour after six that evening, and the President sent word he would receive them at seven.20

Attorney General Edward Bates also made a diary entry after the Cabinet meeting: “Mr. King said that, at first, the document prepared, was against Mr. S.[eward] by name, but that afterwards, it was changed to a more general form, but still, in fact, aimed at Mr. S[eward]. That Mr. S.[eward] said that he was no longer in condition to do good service to the Country, and so, was glad to be relieved from a great and painful burden — and did not wish any effort made to retain him.”21

On December 20, Welles wrote, “Preston King called at my house this evening and gave me particulars of what had been said and done at the caucuses of the Republican Senators,—of the surprise he felt when he found the hostility so universal against Seward, and that some of the calmest and most considerate Senators were the most decided; stated the course pursued by himself, which was frank, friendly, and manly. He was greatly pleased with my course, of which he had been informed by Seward and the President in part; and I gave him some facts which they did not. Blair tells me that his father’s views correspond with mine, and the approval of F.P. Blair and Preston King gives me assurance that I am right.”22

Less than two months later in February 1863, the New York State Legislature replaced King with Edwin D. Morgan. King’s replacement was not necessarily foreordained. New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, attorney Dudley D. Field, and New York Mayor George Opdyke all wanted the Senate nomination. “We offered to reelect King, if they would consent,” political boss Thurlow Weed wrote John Bigelow, the U.S. Consul in Paris. When the trio declined to withdraw, Republicans selected outgoing Governor Morgan as their candidate.

It was a confusing political scenario. Morgan said he deferred to King’s reelection, “I requested friends at Albany…not to present my name if Mr. King could combine strength enough to secure his nomination by the Union Congress.”23 But King lacked either strong popular support or the strong backing of Thurlow Weed. According to the diary of Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, “The organization of the New York Legislature has been finally accomplished. If Weed does not go for Seward for the Senate, — which is at the bottom of this movement, — he will prop Morgan. King, their best man, is to be sacrificed. I do not think Weed is moving for the Senatorship for himself, yet it is so charged.”24 In the Republican caucus on February 2, King received only 16 votes compared to 25 for Morgan, 15 for former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson, 11 for upstater Charles Sedgwick, 7 for New York City attorney David Dudley Field and 6 for New York Times editor Henry J. Raymond. Morgan became the Republican nominee and the victor in the legislative election.

King friend Gideon Welles wrote that “I know of no one who can, just at this time, make good the place of King. He has been cheated and deceived. The country sustains a loss in his retirement. He is honest, faithful, unselfish, and earnestly patriotic.”25 Out of office, King continued to give the President advice, writing him in July 1863 to urge continuation of military conscription:

I am requested by some very good men here to write to the President and protest against any abandonment or suspension of the draft I have not supposed it would be abandoned or suspended I regard it as essential to carry out the draft faithfully and impartially according to law even if every man called for may not be deemed absolutely necessary Those who cheerfully go into the service under the draft have a right to expect equal and impartial justice at the hands of the Government and the friends of the Government feel and say that it is better to have more men in the field than are absolutely required than not to have enough There should be enough & margin enough to leave no doubt any where that there is enough A full draft divides and lightens the burden and the labors of those who go and makes early and complete success over the insurgents certain It will not do for the Government to yeild [sic] the execution of the law and its own declared purpose to apprehension or threats of violence or to solicitations from any quarter The Public confidence in the justice and impartiality of the Government and in its power and confidence in itself must be maintained[.] The call by the draft shows the Government estimate of the force that it wanted and there should not be any diminution of that force by the action or consent of the Government. The interest felt in the condition of public affairs and the state of the Country is intense and the operations of the draft carry home the feeling and discussions to every household –26

Senator King played an important role at the Republican National Convention in 1864 — though this time the Empire State’s favorite son was another former Democrat, former Senator Daniel Dickinson. King’s candidate was Tennessee’s anti-War Democrat, Andrew Johnson. “The convention opened on June 7, at noon. Enthusiasm prevailed among the delegates. A heated debate over the admission of one of two sets of delegates from Missouri resulted in the seating of the Radicals, who opposed Lincoln, and the exclusion of the Blair-Union men, who controlled the federal patronage in Missouri,” wrote historian William Ernest Smith:

Preston King, a member of the committee on credentials, read the report which recommended the seating of the anti-Blair delegates. ‘The Convention rocked with joy, and all proceedings were suspended while the tide of applause rose and ebbed. Then the report was put to a vote. State after state cast votes for its approval, until Maryland and Delaware were reached, and they voted ‘aye’ too! Once more the Convention broke into thunderous applause, which still echoed around the hall when it was announced that the anti-Blair delegates had been seated by a vote of 440 to 4. In effect, the Republican party served notice upon Lincoln that it had no use for the ‘Blair malcontents.'”27

King, a lawyer and founder the St. Lawrence Republican, was considered for several political appointments by the Lincoln Administration after leaving the Senate. When Simeon Draper rather than King was appointed Collector of Customs for the Port of New York in September 1864, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was appalled. He wrote in his diary: “I also learn from [Montgomery] Blair that [Salmon P.] Chase opposed the appointment of Preston King, saying he was not possessed of sufficient ability for the place. Gracious heaven! A man who, if in a legal point of view not the equal, is the superior of Chase in administrative ability, better qualified in some respects to fill any administrative position in the government than Mr. Chase! And in saying this I do not mean to deny intellectual talents and attainments to the Secretary of the Treasury. Mr. [William P.] Fessenden also excepted to King, but not for the reasons assigned by Mr. Chase. It is because Mr. King is too obstinate. He is indeed, immovable in maintaining what he believes to be right, but open always to argument and conviction.”28

King himself did not receive his patronage reward until after President Lincoln had been assassinated. Nor did King’s appointment as Collector of Customs in New York in August 1865 lead to a happy ending. King, who had not want to take the post, drowned when he apparently committed suicide by jumping off a ferry in New York Harbor.

Footnotes

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 197 (December 16, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 523 (February 13, 1864).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 265.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864, p. 277 (June 26, 1862).

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 299.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 363.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 283.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 174.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 261, 265.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Preston King to Abraham Lincoln, January 11, 1861).

- David Morris Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 234 from Thurlow Weed Barnes, Weed, p. 309 (Letter of Preston King to Thurlow Weed, December 7, 1860).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Preston King to Abraham Lincoln, September 23, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 355.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 354.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 345.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 194 (December 19, 1862).

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 269 (December 19, 1862).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 202 (December 20, 1862).

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 187.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 231 (January 28, 1863).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 232 (February 3, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Preston King to Abraham Lincoln, July 29, 1863).

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, .

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 138 (September 5, 1864).

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 365-366.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 300.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861, Volume II, p. 199.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 360 (Gideon Welles, paper in Illinois State Historical Library).