The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for the murder of P. Barton Key, Esq.

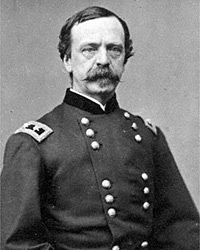

Daniel Sickles was an expert at reinventing himself and ingratiating himself with presidents and the public. Before the Civil War in 1859, Congressman Sickles had been arrested for killing his wife’s lover, District of Columbia District Attorney Philip Barton Key. Before shooting Key, Sickles shouted: “Key, you scoundrel, you have dishonored my house — you must die!”1 Key and Sickles’ wife weren’t the only ones dishonoring the Sickles house. However, in his own extramarital affair, Sickles showed considerably more discretion than did his wife — who carried on her trysts just a few blocks from their home on Lafayette Square. Congressman Sickles conducted his own adultery in a Baltimore hotel.

Sickles was an accomplished comeback artist, had been a prominent proponent of James Buchanan’s presidential candidacy in 1856; he had served as Buchanan’s diplomatic aide when Buchanan was U.S. Minister to England under the Pierce Administration. Such was his relationship with President James Buchanan that the President himself intervened to try to suppress evidence in the murder case. With the help of prominent attorney Edwin M. Stanton, Sickles was acquitted on grounds of temporary insanity.

Sickles also had a talent for creating enemies — exacerbated by his acquittal for murdering his wife’s lover. He was feted for the acquittal but damned for his reconciliation with his wife. “By that simple act of what ordinarily would be considered Christian charity, Dan produced an incredibly swift — and unforgiving — turnaround in public opinion. The public could condone murder as retribution for adultery, but it could not condone a murder’s willingness to forgive,” wrote Nat Brandt in The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder.2

Throughout his life, Sickles seemed to specialize in outrageous behavior — such as flaunting his mistress, madam Fanny White, whom he had introduced to the Queen Victoria when Sickles was posted as a diplomat in London in. Later in life, as U. S Minister in Madrid, he seduced the former Queen of Spain. Within months of his murder acquittal, Sickles had begun a political comeback. By December 1860 when southern States started seceding, Sickles proclaimed in Congress that “in the event of secession in the South, New York City would free herself from the hated Republican ‘State’ government of New York and throw open ports to free commerce.”

But Sickles was nothing if not sensitive to the currents of public opinion. At the beginning of the Civil War, he reinvented himself as a Union militia commander, but without the proper governmental authorizations. When Republican Governor Edwin D. Morgan ordered that most of the companies which he had raised be disbanded, Sickles took his problem to the White House. Biographer Thomas Keneally wrote: “According to what Dan later told his chaplain, [Joseph] Twichell, the Republican Lincoln saw the peril more quickly than Sickles did. ‘What will the governors say if I raise regiments without their having a hand in it?’ He asked. Dan, never without a constitutional reference, urged Lincoln to consider the authority contained under the head of the Power to Raise Armies.” Keneally wrote: “It was a confusing and frantic time for Lincoln, but he was attracted to the worldly little New Yorker who wanted to bring his men into action for the Union. Lincoln called in his Secretary of War, Simon Cameron….. Lincoln and Cameron ordered that Dan keep his men together until they could be inducted by United States officers.”3

Dan Sickles didn’t obey the usual rules. Even after his murder acquittal, Sickles demonstrated this quality when he decided to raise Union troops after Fort Sumter. According to historian James A. Rawley, Sickles exercised “an influence among hesitant Hibernians not to be ignored by Morgan or Lincoln. After the call for 75,000 militia Sickles notified Cameron. ‘The city of New York will sustain the Government. The Herald will declare tomorrow for the Administration. Democrats are no longer partisans. They are loyal to the government and the flag.”4 Sickles was authorized to raise five regiments and given a general’s commission — outside the usual quota for New York. Sickles, as usual, exaggerated his accomplishments. He claimed to have a non-existent brigade ready for muster. Rawley noted that “Not until July 23 did Sickles have one regiment ready, two and one-half months after the overenthusiastic Dan had declared he had a brigade ‘already organized.”5 Because of the government’s experience with Sickles, it issued an ban on such recruiting outside of normal channels.

“While most public figures seek to avoid controversy and scandal, ‘Devil Dan’ Sickles seemed to embrace them,” wrote biographer Gary R. Rice. “As both a political and military figure, he openly drank, defied authority and womanized, making a name for himself as one of history’s most colorful characters. From his mid-30s until his death at age 94, he was continually embroiled in some sort of financial, legislative, sexual or homicidal crisis.”6 Nevertheless, even so perceptive an observer as skeptical New York attorney George Templeton Strong observed that “there are judicious men who rate Sickles very high.”7

Sickles even courted disaster with First Lady Lincoln. When Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln visited his division at the front in the spring of 1862, Sickles sought to cure what he viewed as the President’s melancholy. He arranged for several young women to launch an assault of kissing on the presidential face. Mrs. Lincoln was not pleased when she learned of the episode — which was spearheaded by a woman named Princess Salm-Salm. President Lincoln tried to break the ice that night by saving “I am told, General, that you are an extremely religious man.” After General Sickles accurately denied that label, President Lincoln quipped: “I believe that you are not only a great Psalmist, but a Salm-Salmist.”8

On the trip back to Washington this next day, Sickles reinserted himself in the good graces of Mrs. Lincoln. Sickles was a talented story teller — especially when the story was his own. He used those stories to entertain Mary Lincoln. “And if such talents did not suffice, whom did he not know in Europe? Why, King Louis Philippe, Lamartine the poet-president, Thiers, Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo, Louis Napoleon, and Lord Palmerston, all of them his intimates,” biographer Thomas Keneally, author of the aptly-named American Scoundrel.9

Many Civil War figures played multiple roles. Sickles was no exception — he was a politician, general, lawyer, and sycophant. All these roles came into play in early 1862 when he was called on to defend his friend Henry Wikoff against charges that he had stolen a pre-release copy of the President’s message to Congress from the White House. A Congressional committee headed by Representative John Hickman set out to determine the source of the leak. “Although the identity of the Herald‘s source was tangential at best, Hickman determined to explore it to the end and subpoenaed Wikoff. The latter admitted that he had passed the information to a Herald reporter but refused to divulge his source. On February 10, 1862, Hickman demanded that he answer the committee’s question on this subject and gave him two days in which to respond. When Wikoff remained obdurate, Hickman had him brought before the House as a contumacious witness and placed in the custody of the sergeant-at-arms until he should purge himself of contempt,” wrote historian Allan G. Bogue.10

General Sickles visited Wikoff in jail and tried to help him. Sickles biographer Keneally wrote: “Over the next day as one journalist described it, Sickles ‘vibrated’ between Wikoff’s place of imprisonment, the White House, and the house of Mrs. Lincoln’s chief gardener, John Watt. Sickles was stitching a deal that was meant to save Mrs. Lincoln. Then he himself was summoned as a witness, disclaimed any knowledge of the source, and was threatened with imprisonment. But he had already arranged that all blame would go elsewhere. He suggested that the Judiciary Committee summon [John] Watt, the White House gardener.”11

According to Keneally, “Mr. Watt testified that he had seen the document on the President’s desk, had perused it, remembered it — for he claimed to have an extraordinary memory — and recounted it to Wikoff the next day, word for word.”12 Meanwhile, the Washington rumor mill had been activated. “Stories soon spread like wildfire that the President’s wife had been the betrayer who had given Wikoff the speech,” wrote Ishbel Ross. “Deeply embarrassed, Lincoln went to the Capitol and appealed to the Republicans on the committee to spare him from disgrace; thereupon Watt’s story, which exonerated Mrs. Lincoln, was accepted as the truth. Dan Sickles defended Wikoff, but according to Ben: Perley Poore, he was so excitable that he almost landed in jail himself.”13

“The arrest of the tarnished courtier had been generally regarded as a joke,” wrote historian Margaret Leech, “but the imprisonment of a prominent Democrat, wearing the uniform of his country, would have been a serious matter, and in the end the Judiciary Committee concluded to exercise self-restraint.”14 Although Sickles managed to save Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln from potential embarrassment, “Wikoff was no longer as welcome as the White House,” noted Keneally.15 With time, however, Sickles would become a fixture at Mrs. Lincoln’s evening salon.

Sickles next came to public attention on the second day of the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. According to Union Colonel James C. Biddle, “When [General George Meade] arrived on the ground, at about four P.M., he found that General Sickles, instead of connecting his right with the left of General Hancock, as he had been ordered to do, had thrown forward his line three-quarters of a mile in front of the Second Corps, leaving Little Round Top unprotected, and was, technically speaking, ‘in air’ — without support on either flank. General Meade at once saw this mistake, and General Sickles promptly offered to withdraw to the line he had been intended to occupy, but General Meade replied: ‘You cannot do it. The enemy will not let you get away without a fight.’ Before he had finished the sentence, his prediction was fulfilled. The enemy opened with artillery from the woods on our left, and the action was begun.”16

Sickles’ disobedience was either brilliant or idiotic, depending on the military historian. According to historian James M. McPherson, “Sickles unwise move may have unwittingly foiled Lee’s hopes. Finding the Union left in an unexpected position, [Confederate General James] Longstreet probably should have notified Lee. Scouts reported that the Round Tops were unoccupied, opening the way for a flanking move around to the Union rear. Longstreet’s division commanders urged a change of attack plans to take advantage of this opportunity. But Longstreet had already tried at least twice to change Lee’s mind. He did not want to risk another rebuff. Lee had repeatedly ordered him to attack here, and here he meant to attack.”17 A New York World reporter recorded: “About six o’clock P.M. silence, deep, awfully impressive, but momentary, was permitted, as if by magic, to dwell upon the field. Only the groans — unheard before — of the wounded and dying, only a murmur, a warning memory of the breeze through the foliage; only the low rattle of preparation of what was to come embroidered this blank stillness. Then, as the smoke beyond the village was lightly borne to the eastward, the woods on the left were seen filled with dark masses of infantry, three columns deep, who advanced at a quick step. Magnificent! Such a charge by such a force — full forty-five thousand men, under [A.P.] Hill and Longstreet — even though it threatened to pierce and annihilate all who beheld it. General Sickles and his splendid command withstood the shock with a determination that checked but could not fully restrain it. Back, inch by inch, fighting, falling, dying, cheering, the men retired. The rebels came on more furiously, halting at intervals, pouring volleys that struck our troops down in scores. General Sickles, fighting desperately, was struck in the leg and fell.”18 His leg had to be amputated.

“Dan Sickles came to Washington on a stretcher, one leg shot off and amputated above the knee. Bystanders marveled at his imperturbable face, as he lay with folded arms on the stretcher,” wrote historian Margaret Leech.19 Sickles henceforth maintained a running defense of his actions at Gettysburg. “I met General Sickles at the President’s to-day. When I went in, the President was asking if Hancock did not select the battle-ground at Gettysburg. Sickles said he did not, but that General [Oliver] Howard and perhaps himself, were more entitled to that credit than any others. He then detailed particulars, making himself however, much more conspicuous than Howard, who was really used as a set-off,” reported Navy Secretary Gideon Welles three months later.20 A few days later, President aide John Hay wrote in his diary: “Sickles came to my room this morning. He thinks Lee should have been attacked on his last advance. He says the Army of the Potomac has made the usual mistake of waiting for a perfectly sure thing.”21

Welles wrote: “Allowance must always be made for Sickles when he is interested, but his representations confirm my impressions of Meade, who means well, and, in his true position, that of a secondary commander, is more of a man than Sickles represents him — can obey orders and carry out orders better than he can originate and give them, hesitates, defers to others, has not strength, will, and self-reliance.”22 Hay wrote: “I could not help thinking how much happier Sickles was today sitting curled up in a boyish attitude on my sofa or stumping around my room on his one leg talking pleasantly the while, in the broad sunshine of fame and popular favor, than ever before. He has wiped out by his magnificent record all old stains and stands even in his youth sure of an honored and useful life. One leg is a cheap price to pay for so much o f the praise of men and the approval of his own conscience.”23

In and out of Congress, Sickles repeatedly tested the limits of public convention. Sickles chronicler Nat Brandt wrote: “Dan had the leg saved, and for many years after the war the splintered bone was displayed at the Army Medical Museum in Washington. Traditionally, on the anniversary of the battle, Dan would visit the exhibit there. Later the leg was put on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution.”24 Sickles paid more attention to his missing leg than he did not to his wife Teresa — with whom he had briefly reconciled after his murder trial. Instead, Sickles had allowed Henry Wikoff to keep tabs on her. Brandt wrote: “After the battle, Dan returned on crutches, his pants leg pinned up, to New York, where a celebration in his honor was held. But Teresa was not there to join in his homecoming, and over the Christmas-New Year’s holiday period that year Dan took a suite, alone, at a hotel on lower Fifth Avenue instead of being at home. Officially, he gave his business address as 79 Nassau Street, where he had maintained a law office with his father, and his home address either as Bloomingdale, or ‘foot of West 91st Street,’ though in truth he was not living at home and apparently rarely, if ever, spent time with Teresa.”25

Mr. Lincoln was not above taking advantage of those who took advantage of him. Historian Hans Trefousse wrote: “In May 1864 the president sent General Daniel Sickles…to Nashville on a fact-finding trip. While Sickles denied that he was there to sound out or assess [Tennessee Governor Andrew] Johnson, it is most likely that that was precisely part of his mission. At any rate, the president apparently mentioned his preference for the governor not only to McClure and Cameron, but, but also to others: Abram J. Dittenhofer, a New York Lincoln supporter of Southern antecedents, the president’s old friends Ward Lamon and Leonard Swett of Illinois, and S. Newton Pettis, the western Pennsylvania attorney whom he had appointed a judge in the Colorado Territory, all knew about his wishes, as did William O. Stoddard…If firm contemporary substantiation is lacking, circumstantial evidence would generally seem to bear out McClure’s account.”26 Sickles claimed that President Lincoln told him that spring that he did not want openly to seek reelection. “To avow oneself a candidate for the presidency at this time — to step forward and avow oneself ready to assume the heavy burdens which must come to the president for four years — is something that no man should do. And the people might rightly look with disfavor and suspicion upon one who openly declared that he was ready for the next four years to assume these burdens.”27

But Sickles was not content to do errands for the President. He wanted to be restored to command. In the summer of 1864, he enlisted friends to urge the President to restore him to military duty — but the President never took that risk. At least one Republican friend suggested to President Lincoln that such an appointment would be politically popular in New York at a key point in the presidential campaign. At the beginning of September, Sickles himself wrote Mr. Lincoln:

I hope you will have leisure to give some attention to the claims made by the City of New York for allowances on account of the recruits furnished to the Navy, it seems to me the claim is just, and there is a general belief among men of all parties here that the demand might be allowed. It is certainly very desirable to relieve the Government of the necessity of enforcing the draft in this City, in the existing state of popular opinion, if it can be done upon fair grounds, consistent with the dignity of the Government and without injustice to other parts of the Country. Unfortunately, a vast number of Southern refugees most of them disloyal have been allowed to congregate here and in the suburbs, estimated at not less than One hundred thousand, many of them men of wealth and ability, & they are exercising the worst influence upon the ill disposed elements of our population especially the Irish and German laborers. If this claim for Naval recruits be allowed there will be no doubt whatever that the quota of this city will be promptly filled by volunteers, and substitutes.

In consequence of the expiration of the terms of service of many of the New York and New Jersey Regiments belonging to my old Corps, and the consolidation of others, there are some fifteen or twenty numbers no longer represented in the Service, and I am confident that with proper and sufficient facilities I could reorganize and fill up my old Army Corps (3rd) with new Regiments made up partly of veterans and the remainder of volunteers, which would replace the Regiments that have gone out of Service. There is one division of my Corps now left in the field it would not be necessary to disturb this until I had completed the two new divisions. With the local aid & cooperation I could command, a very large number of men can be obtained who would not otherwise enter the service.28

Controversy followed Sickles throughout the rest of his long life. After the Civil War, Sickles served as Union commander in the Carolinas. He returned to Congress from 1893 to 1895. He was forced from his post as chairman of the New York State monuments commission in 1912.

Footnotes

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 127.

- Nat Brandt, The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder, p. 190.

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 222.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 149-150.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 150.

- Gary R. Rice, “Devid Dan Sickle’s Deadly Salients”, .

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 323 (May 14, 1863).

- Don E. And Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 406 (New York Tribune, May 21, 1899).

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 225.

- Allan G. Bogue, The Congressman’s Civil War, p. 69-70.

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 236.

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 236.

- Ishbel Ross, The President’s Wife: Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 137.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 368.

- Thomas Keneally, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p. 236.

- Annals of the War, p. 211 (James C. Biddle, “General Meade at Gettysburg”).

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 657.

- Annals of the War, p. 427 (James Longstreet, “Lee in Pennsylvania”).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 317.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 472 (October 16, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 95 (October 20, 1863).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 473 (October 16, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 95 (October 20, 1863).

- Nat Brandt, The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder, p. 206.

- Nat Brandt, The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder, p. 206.

- Hans Trefousse, Andrew Johnson, p. 178.

- Don E. And Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 406 (New York Times, July 10, 1891).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Daniel E. Sickles to Abraham Lincoln, September 1, 1864).