On Saturday, July 11, President Lincoln telegraphed his son Robert at the New-York Fifth Avenue hotel in Manhattan: “Come to Washington.”1 It is unclear why President Lincoln sent the telegram to his draft-age son — although possibly it was because Robert’s mother had been injured in a serious carriage accident on July 2. There is little mystery, however, about what happened in New York City that day.2

The draft was set to be on Saturday, July 11. William Alan Bales wrote in Tiger in the Streets: “There were two offices: one at 1190 Broadway near Twenty-ninth Street; another at 677 Third Avenue near the corner of Forty-sixth Street. The Saturday drawing was in the office at Third Avenue.”3 Historian Stewart Mitchell noted: “The neighborhood was very much uptown in 1863, not by any means respectable, and more than three miles as the crow flies from city hall, then situated at the centre of New York.”4

Historian David Long, Jewel of Liberty: “A number of enrollees in each district of the city were to be chosen by lot from the list of eligible men; this would proceed until each district’s quota was met. The idea was to call up 20 percent of the men on the lists. However, the share of draftees from each district varied according to the number of men who had already enlisted from that district. James McPherson points out, ‘There were numerous opportunities for fraud, error, and injustice in this cumbersome and confusing process.’ Ultimately, because of the numerous means for avoiding actual service, only 7 percent of those chosen ever served in the Union military.” The draft of 1200 New Yorkers proceeded without disturbance that Saturday.

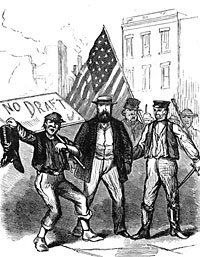

But, noted Long, “that evening and on Sunday, in pubs and on street corners of the city’s tenement districts, groups of working-class men imbibed alcohol and anti-black rhetoric in generous doses. Their mood grew increasingly ugly.5 By Monday, the ugly mood was incendiary.”6 Historian John William Leonard wrote: “Sunday was used by the disaffected and desperate to plan what proved to be the most terrible and desperate riot that ever blackened the annals of New York. Some working men who had been drafted, aided by several political agitators, stirred up an opposition to further enrollment under a system which placed, as they claimed, its entire burden upon the poor.

One of Mr. Lincoln’s aides, William O. Stoddard, had asked to take a leave from Washington to recover from overwork and malaria. Accompanied by his brother Henry, Stoddard went to New York City where “we walked blindly into the Draft Riot of 1863”. According to Stoddard, “the actual operation of the draft began at the Marshal’s or Enrollment Office of the Third Subdivision of the Ninth Congressional District, at 677 Third Avenue, corner of Forty-sixth Street. The drawings were made by means of a lottery wheel and proceeded throughout the day without any interruption whatever. Twelve hundred and thirty-six names were drawn, leaving only 264 men to be obtained in order to complete the quota of that subdivision. There was no question raised by anybody as to the fairness and impartiality of the day’s work.”7 Stoddard later wrote:

We took our breakfasts early that July morning in New York City Hall Park. Not a word of any uprisings such as were going on uptown had been heard. Suddenly I saw a cart, driven furiously, on which lay a Negro, while a small mob of ruffians appeared to be trying to drag him off. In another direction a Negro was being chased and maltreated, and the air was full of dire exclamations and prophecies.A first I did not understand the matter, but the truth dawned on me as my blood rose hotter, and I went back to my room. There was my pistol belt, knife and all, and the weapon was of heavy calibre. Henry had none, so I gave him mine, and we went hastily to Maiden Lane, where the gun stores were, to get me a new outfit. I was just in time, for hardly had I buckled on my longer-barreled, heavier shooting iron, when all those stores were closed by order of the police, and by the fear of their owners that they would soon be looted if they were open. We had plenty of ammunition, but where we were to use it we could not guess. The idea was in my mind that any mob would be likely to plunder the moneymen, and so I led the way toward Wall Street.When we reached the corner of the Sub-Treasury, there were on the steps was General Ward B. Burnett, organizing a company of volunteers that promised to be a good one. I knew that he had commanded the First New York Volunteers in the Mexican War and was accounted a brave, capable officer. That was the man to serve under, and we at once fell into line, recalling our soldier experience in the Rifles. The General swore us in, gave us instructions, looked very cool, and determined but a little bloodthirsty, and we were posted. That is, we were put temporarily in charge of the Treasury, under the impression that there was to be an immediate attack on it. Later we were transferred to the portico of the Custom House, where we kept company with a wide-mouthed mountain howitzer.”

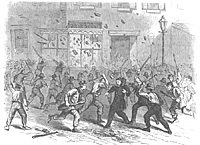

The riots had an anti-Protestant as well as anti-upper class basis. According to Stoddard, there was a clear class division in the rioters: “I saw a surging, swaying crowd coming up Broadway, whooping, yelling, blaspheming and howling, demoniacs such as no man imagined the city of New York to contain. There were women among them and half-grown boys, but none of them seemed to be American. Who were they? They carried guns, pistols, axes, hatchets, crowbars, pitchforks, knives, bludgeons — the red flag. ‘Down with the rich men! Down with property! Down with the police!'”8

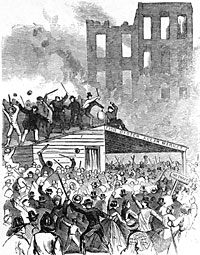

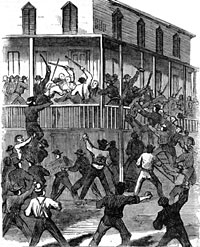

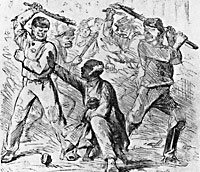

Monday was the most violent day of the riots. Federal officials attempted to restart the draft process but protestor attacked the enrollment office on Third avenue. Workplaces emptied as workers joined the mob — who even attacked Police Superintendent John A. Kennedy. At 10 a.m., “Superintendent of Police Kennedy while on a tour of inspection in citizen’s clothes was recognized by a mob at Forty-sixth Street and Lexington Avenue, containing many criminals who had too good cause to know him. He was beaten into insensibility and left to drown in a puddle of water, when rescued by a friend,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt.9 The rioters gathered in front the New York Tribune office, trashed the offices on the first floor. Violence spread throughout Manhattan. The draft office at Third Avenue and 46th Street was destroyed. Only the courageous efforts of New York City police prevented the mob from destroying police headquarters on Mulberry Street. A group of invalid soldiers pressed into duty was beaten.

Iver Bernstein contended in The New York City Draft Riots: “The lines between constituencies were sometimes blurred. Some Germans appeared among Tuesday’s and Wednesday’s rioters, some Irish left the streets Monday afternoon. Occasionally artisans rioted through the week, and sometimes industrial workers and laborers dropped out of the crowds early on. But the most clear and abrupt social division was that between journeymen in the older artisan trades, who limited their participation to Monday’s demonstrations, and workers in newer industrial occupations and common laboring, who persisted in the midweek revolt. By Tuesday the riot had entered a new phase in which the animus came primarily from Monday’s most violent rioters.”10

The authorities had a difficult time mobilizing what little resources they had. “Mayor Opdyke got word of the trouble at about a quarter to ten in the morning and telegraphed to Governor Seymour three times in one day, trying to reach him by way of Albany,” wrote historian Stewart Mitchell.11 But Seymour was in New Jersey and wasn’t reached by telegraph until much later in the day” Attorney George Templeton Strong went to the St. Nicolas Hotel on Monday, July 13 to beg “that martial law might be declared. [Mayor George] Opdyke said that was Wool’s business, and Wool said it was Opdyke’s, and neither would act. ‘Then, Mr. Mayor, issue a proclamation calling on all loyal and law-abiding citizens to enroll themselves as a volunteer force for defense of life and property.’ ‘Why, ‘quoth Opdyke, ‘that is civil war at once.’ Long talk with Colonel Cram, Wool’s chief of staff, who professes to believe that everything is at it should be and sufficient force on the ground to prevent further mischief. Don’t believe it. Neither Opdyke nor General Wool is nearly equal to this crisis. Came off disgusted. Went to Union League Club awhile. No comfort there. Much talk, but no one ready to do anything whatever, not even to telegraph to Washington.”12

Strong himself was ready. “We telegraphed, two or three of us, from General Wool’s rooms, to the President, begging that troops be sent on and stringent measures taken. The great misfortune is that nearly all our militia regiments have been despatched to Pennsylvania. All the military force I have seen or heard of today were in Fifth Avenue at about seven P.M. There were two or three feeble companies of infantry, a couple of howitzers, and a squadron or two of unhappy-looking ‘dragoons.'”13

On Monday, Provost Marshal General. James B. Fry telegraphed Acting Assistant Provost. Marshal General Robert Nugent in New York City: “Apply to General Wool for force, if you have not done so, to quell the riot reported in Third avenue, provided it is serious. You had better concentrate your Invalid Corps with other forces, and act directly against the rioters, in conjunction with the city police. I have telegraphed General Wool. Report condition of affairs.” Fry telegraphed General Wool: “It is reported that a serious riot is in progress in Third avenue, and that the provost marshal’s office has been burned. Will you please furnish at once all the force you can to enforce the enrollment act, provided the necessity for it is as represented?”14 Later Monday, Fry telegraphed General John Wool on Monday: “Adjutant General Sprague, now here, informs me that Colonel [Henry L.] Lansing, at New Dorp, has 300 or 400 men available for the riot, and also two companies, under Major [George W.] Scott, on Riker’s Island. General Sprague says these are all subject to your orders. The marines and sailors at the navy yard and receiving ship will, I presume, co operate, if applied to by you.”15

“No black person was safe. Rioters beat several, lynched a half-dozen, smashed the homes and property of scores,” wrote historian James McPherson. “Mobs also fell upon several business establishments that employed blacks. Rioters tried to attack the officers of Republican newspapers and managed to burn out the ground floor of the Tribune while howling for Horace Greeley’s blood. Several editors warded off the mob by arming their employees with rifles; Henry Raymond of the Times borrowed three recently invented Gatling guns from the army to defend his building.”16Biographer Augustus Maverick wrote: “A signal illustration of Raymond’s courage in the presence of danger was given in the terrible ‘Riot Week’ of July 1863, when, under pretence of resisting a draft for troops, the mob of New York committed the vilest excesses, and the day held undisputed possession of the city, encouraged the deeds of violence by the Governor of the state and by incumbents of judicial office, and sustained by the traitorous journals of the day. The offices of the loyal newspapers were put in posture of defence, to avert apprehended attack, was the proprietors of theTimes planted revolving cannon in their publications office, and provided great store of other death-dealing weapons with which to repel invasion. Beneath the spector of battery and bomb, Raymond steadily poured a gallant fire into the ranks of the mob, its official supporters, and the editors who encouraged it.”17 Maverick one other unlikely defensive weapon which reportedly protected the Times: Copperhead editor Benjamin Wood standing in the doorway and lecturing would-be arsonists about property rights.

On both Monday and Tuesday some leading Republicans were clearly targeted by rioters. Mayor George Opdyke’s house on Fifth Avenue was attacked. The office of the New York Times prepared itself for attack. The home of New York Postmaster Abram Wakeman was torched. The offices of the New York Tribune came under direct attack. TribuneEditor Horace Greeley later wrote:

On the 13th of July, 1863 (the first day of the Draft Riots in our city), the editor of the Tribune was visited in his office about midday by a devoted friend, who urged and entreated him to accompany the said friend to his home, a few miles distant. That friend assured him that he knew that he life of said editor was to be taken forthwith — that it had been plotted and settled that he should be an early and certain victim of the ruffian mob then howling about the Tribune office, and inciting each other to the assault, which they actually made at dusk that night, when they smashed the windows, furniture, etc., and set fire to the building, but were promptly routed and expelled by the police. Riot, arson, and pillage were then rife in different sections of our city, of which the rebel mob appeared to have undisputed possession. The editor (who writes this) informed his friend that nothing would induce him to leave the city — that he was where he had a right to be — and where he should remain. That friend, after exhausting remonstrance and entreaty, left him to his fate, not expecting to see him again. After five P.M. of that day, the editor, having finished his work at the office, went over to Windust’s eating-house for his dinner, passing through the howling mob for nearly the entire distance, and recognized by several of them. Two friends accompanied him, but not at his invitation or suggestion. Neither of the three was harmed. At Windust’s dinner was ordered and eaten exactly as on other days, but in the largest room in the house, without the shadow of hiding or concealment of any kind. Dinner finished, the editor took a carriage and drove to his lodging, where he resumed writing for the Tribune, and continued it through the evening, sending down his copy to the office, and being visited thence by friends who informed him of the mob’s assault, and the narrow escape of the building and contents from destruction. Remaining all night at his lodging, he returned next morning to the office (now being armed), saw from a window the mob howling in its front hastily repaired to the City Hall Park, there to listen to a harangue from Horatio Seymour, and remained there nearly to the close of the day [Tuesday], when he was finally induced to leave by the representation of the good and true soldier who commanded it as fortress, that he would prefer that the mob should not be provided with the extra inducements for assault which the known presence of Mr. Greeley in the building would afford. He returned to the office next morning, though the first hackman to whom he applied refused to let him enter his carriage; and he was in the office nearly throughout each day of that memorable week up to Friday evening, when he (as usual) took the Harlem cars for home at Chappaqua, where he spent the Saturday, as he has done nearly every Saturday, save in winter, for the last fifteen years. And whoever asserts that he at any time that week ‘was hiding under Windust’s table’ is a branded liar and villain, as Mr. Windust, Mr. William A. Hall, and other surviving and most credible witnesses will gladly attest.”18

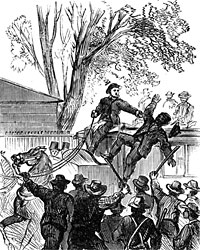

It was a close call for Greeley and his newspaper. “Chanting, ‘We’ll hang old Greeley to a sour apple tree, And send him straight to Hell,’ the mob poured down upon Printing House Square. The police guarding the Tribune were overwhelmed; fires were started in half a dozen spots in the building; desks, tables, type forms, and printing presses were smashed; Greeley and his assistants escaped in the nick of time. The editor was chased into a Park Row restaurant, where he hid under a table,” wrote Oliver Carlson in a biography of rival editor James Gordon Bennett.19

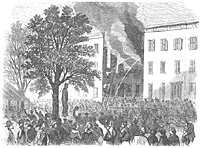

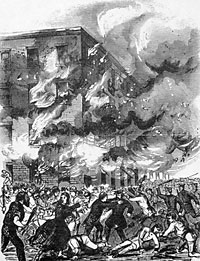

Historian Frank Klement wrote: “The first day’s rioting seemed to be directed at the draft and symbols of authority. The second day’s violence featured attacks upon blacks and their businesses. Some buildings were burned and black men were assaulted and beaten or killed. A mob attacked and burned the Colored Orphan Asylum (all 237 children escaped) — there was no such institution for the orphans of Irish-Americans and German-Americans. Arson and plunder and killings continued for two more days.”20 Noted historian Daniel Van Pelt: “By the heroism and coolness of the attendants the two hundred young inmates were fortunately conducted to a place of safety by a rear door as the raging fiends broke in the front door. The torch was applied in twenty places at once, and the building burned to the ground. From day to day the mob became bolder in their depredations. They went comparatively unresisted over the entire island.”21

Lincoln’s son Robert was still missing on Tuesday but evidently en route to the White House. A worried father sent Robert a telegram: “Why do I heard no more of you?”22 The 14th was also the day that Governor Seymour arrived in the city. He met Mayor Opdyke at the St. Nicholas Hotel around noon and then addressed citizens rioters in front of City Hall. “The Governor made a few remarks intended to allay the popular excitement, and earnestly counseled obedience to the laws and constituted authorities. He also read a letter, containing a statement that the conscription had been postponed by the authorities in Washington,” wrote Major T. P. McElrath. “This speech of Governor Seymour, owing to his well-known affiliation with the opposition, was severely criticised by his political opponents, chiefly on account of his opening it with the words, ‘My friends.’ While he was speaking, however, his previous proclamation showed that he was exerting his influence for suppressing the insurrection, and he could hardly be expected to address a peaceable audience with the invective applicable to red-handed rioters and incendiaries. In his remarks he expressed his belief that the conscription act was illegal, and announced his determination to have it tested in the courts. In dwelling upon these points he may have violated good taste, but it must be borne in mind that his purpose was to soothe an unusual popular excitement, and the end was justified in using whatever reasonable arguments were available for that purpose.”23

On arrival in the city, Governor Seymour “issued two proclamations,” noted historian Sidney David Brummer. “One reminded those who had resorted to violence ‘under an apprehension of injustice that the only permissible opposition to the draft was an appeal to the courts. ‘Riotous proceedings,’ he proclaimed, ‘must and shall be put down. The laws of the State of New York must be enforced, its peace and order maintained, and the lives and property of all its citizens protected at any and every hazard.’ And the Governor threatened that unless the rioters retired to their homes and employments, he would use all the power necessary to restore tranquility to the City. The second proclamation declared the City to be in a state of insurrection — an act of wisdom, since it permitted the complete and legal use of the military, the only power capable of suppressing the disturbance. Of course, the Unionist press did not fail to point out that the Governor had not announced that the laws of the United States must and would be enforced. Appended to one of the proclamations was a request that loyal citizens should enroll at designated places to aid in preserving peace. This idea was carried out.”24

That night, attorney George Templeton Strong wrote in his diary: “At 823 [Broadway — headquarters of the U.S. Sanitary Commission] with [Dr. Henry W.] Bellows four to six; then home. At eight to Union League Club. Rumor it’s be attacked tonight. Some say there is to be great mischief tonight and that the rabble is getting the upper hand. Home at ten and sent for by Dudley Field, Jr., to confer about an expected attack on his house and his father’s, which adjoin each other in this street just below Lexington Avenue.”25

By Tuesday, Union officials in Washington began to understand how serious the situation was when they received telegrams such as this from Provost Marshal, John Duffy: “Headquarters destroyed by the mob. Papers safe.”26 Fry telegraphed Nugent on Tuesday: ” Suspend the draft in New York City and Brooklyn.”27 In another Tuesday telegram, Fry wired Colonel Nugent: “Set your detectives at work to ascertain the names of the ringleaders and other principal men concerned in the late riot, and to get evidence against them, so that they may be arrested and tried.” Provost Marshal General Fry wrote Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on Tuesday.

“The enforcement of the draft was yesterday seriously resisted in the ninth district of the city of New York. The mob, variously estimated in numbers up as high as 30,000, attacked the officers of this bureau in the performance of their duty, and destroyed the building in which the draft had been conducted, and many of the rolls, records, and appurtenances connected with the draft. The military and the police force of the city on duty there were overwhelmed and dispersed.In the present condition of things, I do not think the draft can be made without additional force. I therefore recommend that four regiments of infantry and a battery of artillery be sent immediately to New York City, and, without intending to travel beyond the line of my duty, I would state that I think the public interest, so far as my department is concerned, would be greatly promoted if Major General [Irvin] McDowell can be assigned to such command as will enable him to direct the military operations necessary to enforce the draft in the State of New York and New England. The numbers and importance in this riot are doubtless greatly exaggerated, but I deem it sufficiently serious to justify the suggestions herein made.”28

Episcopal minister Morgan Dix, son of the city’s military commander, later wrote: “Thus the days wore on, with dust and smoke, with fire and flame; with sack of private dwellings and burning of charitable institutions, armories, and draft stations; with blood and wounds, and every imaginable instance of atrocity on the part of the maddened mob, till regiments, hurriedly withdrawn from the front, came speeding back to the city, and we saw the grim batteries and weatherstained and dusty soldiers tramping into our leading streets as if into a town just taken by siege. There was some terrific fighting between the regulars and the insurgents; streets were swept again and again by grape, houses were stormed at the point of the bayonet, rioters were picked off by sharpshooters as they fired on the troops from the house-tops; men were hurled, dying or dead, into the streets by the thoroughly enraged soldiery; until at last, sullen and cowed, and thoroughly whipped and beaten, the miserable wretches gave way at every point and confessed the power of the law. It has never been known how many perished in those awful days.”29

Major T.P. McElrath wrote: “Scenes of violence and carnage, such as I have described, prevailed in the streets of New York from Monday noon until Thursday night. The political sentiment, which displayed itself in the original assault on the draft office, in Third avenue, disappeared after that demonstration, and thenceforward the mob was actuated solely by an instinct of rapine and plunder.”30

Footnotes

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 323 (Letter to Robert T. Lincoln, July 11, 1863).

- William O. Stoddard, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 183-184.

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 122.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 321.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, p. 70-71.

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1909, p. 375.

- William O. Stoddard, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 185.

- William O. Stoddard, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 185.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 415.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 27.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 321.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 337 (July 13, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 337 (July 13, 1863).

- Report of Col. James B. Fry. Provost Marshal General, U. S. Army, with orders, &c.JULY 13-16, 1863.—Draft Riots in New York City, Troy, and Boston.

- Report of Col. James B. Fry. Provost Marshal General, U. S. Army, with orders, &c.JULY 13-16, 1863.—Draft Riots in New York City, Troy, and Boston.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 610.

- Augustus Maverick, Henry J. Raymond and the New York Press for Thirty Years, p. 164.

- Don C. Seitz, Horace Greeley: Founder of the New York Tribune, p. 210-211.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 355.

- Frank Klement, Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads of the North, p. 104.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 418.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 327 (Letter to Robert T. Lincoln, July 14, 1863).

- Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South, Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, p. 301 (T.P. McElrath, “The Draft Riots in New York”).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 321.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 338 (July 14, 1863).

- Report of Col. James B. Fry. Provost Marshal General, U. S. Army, with orders, &c. JULY 13-16, 1863.—Draft Riots in New York City, Troy, and Boston.

- Report of Col. James B. Fry. Provost Marshal General, U. S. Army, with orders, &c. JULY 13-16, 1863.—Draft Riots in New York City, Troy, and Boston.

- Report of Col. James B. Fry. Provost Marshal General, U. S. Army, with orders, &c. JULY 13-16, 1863.—Draft Riots in New York City, Troy, and Boston.

- Morgan Dix, Memoirs of John Adams Dix, Volume II, p. 75.

- Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South, Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, p. 298-299 (T.P. McElrath, “The Draft Riots in New York”).