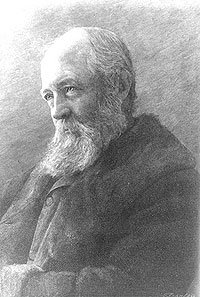

Frederick Law Olmsted was a whirlwind. “was a man of initiative, patience, endless energy, and foresight, but not tact,” wrote historian Allan Nevins. “His decisive acts, stubborn insistence on having his own way, and intensity of temper made enemies.”1 George Templeton Strong wrote after a December 1862 meeting of the commission: “We had much debate also about the relative authority of the Commission (or Executive Committee when the Commission is not sitting) and our executive officer, F. L. Olmsted, to wit, Were he not among the truest, surest, and best of men, we should be in irreconcilable conflict. His convictions as to the power an executive officer ought to wield and his faculty of logical demonstration that the Commission ought to confide everything to its general secretary on general principles, would make a crushing rupture inevitable, were we not all working in a common cause and without personal considerations.”2

Olmsted became involved in the work of the United States Sanitary Commission virtually from its inception in New York City in June 1861. Despite crutches and the lingering effects of a near-fatal riding accident, Olmsted threw himself into the commission’s work. “The chief executive duties were performed by the general secretary of the commission at its central office in Washington; and presently, to fill this post, a frail little man arrived at the capital on crutches,” wrote historian Margaret Leech. “Before the war, Frederick Law Olmsted had traveled widely in the South, and had written books describing social and economic conditions little comprehended in the free States. The vivid and tolerant pages of A Journey in the Back Country and A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States had given many Northerners their first accurate knowledge of slavery. Aside from his writing, Olmsted’s main interest was in farming and horticulture. He was engaged in an unusual profession, that of landscape architect, and he had been made the architect and superintendent of New York City’s Central Park, that project novel in America of a large pleasure ground designed for use of the people.”3

Olmsted chose an unusual career path. “Frederick Law Olmsted set out early and deliberately to make himself a man of influence on his time an on his country. His course, erratic to begin with, found its true direction only after several false starts. Extricating himself from the backwater, farming that was his first enthusiasm, he embarked on journalism and published and entered directly into the mainstream of contemporary American life,” wrote Olmsted biographer Laura Wood Roper. “As a journalist he explored the agitating questions of the day with candor and intelligence and in the space of a decade produced a body of work that was something of a revelation to his pre-Civil War readers, and that offers readers today a clear and credible view of a disputed past. Dropping his literary career to work on the construction of Central Park, Olmsted turned his mind to the problems, already acute, of big-city living. His connection with the United States Sanitary Commission during the war then carried him into the area of the social sciences, the concerns of which dovetailed nicely with those of the work that was his passion and finally his profession, landscape architecture.”4

Olmsted was talented. He has both vision and a talent for organization. He was also naturally impatient and inherently ambitious. Dr. Bellows wrote a Commission ally: “You understand..the glorious and invaluable qualities of our General Secretary, his integrity, disinterestedness and talent for organization, his patriotism. You also understand his impracticable temper, his irritable brain, his unappreciation of human nature in its undivided form and his very imperfect sympathies to weak, mixed, inconsequent people.”5

Olmsted is best known as the landscape architect of Central Park in Manhattan, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the Greensward in Boston, the grounds of the U.S. Capitol Grounds, the National Zoological Park in Washington DC, and the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. But in 1861, he took a leave of absence as Superintendent of Central Park in New York City. For two years, Olmsted set aside landscape architecture and served as the executive director of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. He was driven and determined in all that he did from the time he shipped off for China at age 21.

After receiving his commission appointment in late June 1861, Olmsted moved to Washington and started making the rounds of military camps around the city. He was horrified by what he found and went to work putting pressure on the U.S. government to improve the living conditions of Union soldiers. Olmsted issued an early report in July 1861 in which he stated: “The Secretary…is compelled to believe that it is now hardly possible to place the volunteer army in a good defensive position against the pestilential influences by which it must soon be surrounded. No general orders calculated to strengthen the guard against their approach can be immediately enforced with the necessary vigor. The captains, especially have in general not the faintest comprehension of their proper responsibility; and if they could be made to understand, they could not be made to perform the part, which properly belongs to them in any purely military effort to this end. To somewhat mitigate the result is all that the Commission can hope to do. If the Commission and its agent could be at once clothed with some administrative powers, as well as exercise advisory functions, far more could be done….”6

Olmsted did not shy away from controversy. After the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, Olmsted added the demoralization of soldiers to his list of concerns and prepared a “Report on the Demoralization of the Volunteers” for the Sanitary Commission.” The report was so controversial and so critical of the Army leadership that it was never released. In September 1861 Olmsted wrote President Lincoln in: “The Quarter Master General has informed the Sanitary Commission that some scarcity of blankets is for the present to be apprehended. The Commission proposes to supply hospitals as far as possible from private stores, by which means a considerable quantity will be set free for the men in active service. Without announcing the deficiency the Secretary of the Commission is about to issue a circular soliciting donations and respectfully requests a line from the President recommending the purpose of the Commission to the confidence of the public.”7

The President replied the same day in a letter to Winfield Scott: “The Sanitary Commission is doing a work of great humanity, and of direct practical value to the nation, in this time of its trial. It is entitled to the gratitude and confidence of the people, and I trust it will be generously supported. There is no agency through which voluntary offerings of patriotism can be more effectively made.”8

Olmsted threw himself into his work, according to historian Margaret Leech: “In July of 1861, he shared suffered from the strain; and a fall from his horse, while inspecting the work, had given him a badly broken thigh. Yet his leave of absence for patriotic duty brought him no rest for two laborious years. In July of 1861, he shared with a competent doctor the labor of inspecting twenty camps near Washington. That year, the servants often found him still at work when they came to set the breakfast table. In the spring of 1862, he went to the Peninsula to spend himself in untiring service. His wasted, autocratic face, with its feminine features and straggling mustache, burned with the same harsh flame of consecration that lighted the features of Miss [Dorothea] Dix. But Olmsted had a genius for organization; and, backed by the gentlemen of his board, he developed the Sanitary Commission into an immense and powerful agency for the relief of suffering among the soldiers.”9 Olmsted proved a hands-on manager; he personally oversaw the conversion of steamers into ships for the Hospital Transport Service that evacuated wounded soldiers from the Peninsula and saved many from death.

Olmsted was completely dedicated to the war and the work. “I am well convinced that it is necessary to the safety of the country that the war should be popularized that I can hardly be loyal to the Commission, and the government, while it is required of us to let our soldiers freeze and our armies be conquered for the sake of maintaining a lie. Let the people know that we are desperately in want of arms, desperately in want of money, desperately in want of clothing, desperately in want of medicine and food for our sick, and I believe we should be relieved of our difficulties as a suffocating man is relieved by opening a window,” wrote Olmsted to Dr. Henry Bellows in late September 1861. “It is yet possible to stir the whole North by a confession that we need to put forth a revolutionary strength to resist a revolutionary strength….”10

Olmsted did not confine his opinions to the work of the Commission. In July 1862, he tried to influence military policy as well, writing New York Senator Preston King to urge the enactment of a military conscription act:

As one of your constituents, observing this army from a peculiar point of view, may I tell you what I think of the duty of government to it?If it remains here, the usual dangers of crowded encampments in a hot and malarious climate being aggravated by dissapointment [sic], idleness and home sickness from hope of home hopelessly deferred, it will loose [sic] half its value. And its value as an army, culled by hardship and disease, of its maker constituents, and disciplined and trained by three months’ advance in the face of a strong, vigilant, watchful wiley [sic] and vindictive enemy, is at the present market price of soldiers fully equal to its enormous cost. By one means or another government must save and use it. To this end the Army of the Potomac should be withdrawn, at once, entirely from James river or it should be so rapidly and constantly strengthened that the men will have the utmost confidence that within a month at furthest, they will able to advance on Richmond with certainty of success. For this purpose 50.000 men in regiments already disciplined should be transferred here from localities where they can be which can be abandoned, where they can be dispensed with, or where raw regiments will be able to safely supply their place, and thirty thousand men should be added to the regiments already here and greatly reduced in number force by losses in battle.The latter should be carefully inspected sturdy re conscripts.Conscription would greatly hasten volunteering. It would force a large class of men to serve the country in the only way they can be effectually made to do so. It would not withdraw men from their usual pursuits who are of more value to the community in those pursuits than they would be in the ranks, because the measure of their value is their earnings and these must be sufficient to enable them to enter successfully into competition with government in offerring [sic] premiums for volunteers — as substitutes.Thirty thousand fresh men, each placed between two veteran volunteers, three weeks hence, would add greatly to its strength and diminish but imperceptibly its mobility and efficiency. They would be welcomed by the old volunteers because they would bring to each regiment so much relief from in guard and fatigue duties.The cheif [sic] objection to conscription will be the supposed appearance of weakness which it will exhibit to foreign powers. Does not hesitation to adopt conscription at a crisis like this, illustrate and demonstrate an essential weakness in our form of government for purposes of war, which already is overestimated, and much to our damage and danger abroad?Will it be wholly unpopular? It will convince the people that their government is in downright earnest in its purpose to overcome the rebellion whatever it costs, and that it realizes the fact — spite of the vain glorious boastings of its newspapers, its orators and its generals — that this is not to be accomplished by ordinary small politicians’ small politics, nor without a sacrifice which every citizen, patriotic or otherwise must have a part in. Whatever does this, in my judgment, will be popular.11

Olmsted was pushing for conscription on more than one front. Alexander D. Bache wrote presidential assistant John G. Nicolay two days later: “Fredk Law Olmsted Secr. of the Sanitary Commission was here last week, much distressed in regard to the prospects of the Army of the Potomac, & eagerly urging the sending of reinforcements. We failed to see the President on Saturday, as exhausted by the terrible draughts upon his mind & body, he had retired.” Olmsted had written a letter to President Lincoln which he hoped would be given to the President, who was at that time much preoccupied with the fate of General George B. McClellan’s stalled operation on the Virginia Peninsula. Bache wrote: “Nevertheless as showing the ideas of a true hearted loyal man whose time & talents are given up to the country I have thought that the President might care to see what Mr. Olmsted wrote to him on the 8th, of July & sent to me, not anticipating at all that they were to be so near each other within a day. Will you with your knowledge & tact decide the question & if you agree with me present Mr. Olmsted’s letter to the President at a suitable time.”12 Olmsted wrote:

After having been for three months in the rear of the Army of the Potomac, superintending the business with it, of the Sanitary Commission, I have just spent a day in Washington, where I had the honor of conversing with several gentlemen who are your advisers, or in your confidence. What I learned of the calculations, views and feelings prevailing among them, causes with me great apprehension.In the general gloom, there are two points of consolation and hope, which grow brighter and brighter, opening my eyes suddenly, as I seem to have done, in the point of view of Washington, I may see these and their value, more clearly than those about you. One, is the trustworthy, patriotic devotion of the solid, industrious, home keeping people of the country; the other, the love and confidence constantly growing stronger between these people and their president.Here is the key to a vast reserved strength, and in this rests our last hope for our country.Appeal personally to the people, Mr. President, Abraham Lincoln to the men and women who will believe him, and the North will surge with a new strength against which the enemy will not dare advance. Then, can not fifty thousand men, now doing police and garrison duty, possibly be drawn off with safety, and sent within a month to McClellan? Add these to his present seven times tried force and he can strike a blow which will destroy all hope of organized armed resistance to the Law Without these, the best army the world ever saw must lie idle, and, in discouragement and dejection, be wasted by disease.13

Three months later, Olmsted sent another suggestion to the President — via John G. Nicolay — about how to publicize the draft Emancipation Proclamation in the South. He enclosed some books — probably the ones he had written about the South — and wrote:

The Proclamations of the President with regard to the Colonization, compensated voluntary emancipation, and forced legal emancipation as an act of War, of the slaves, are obviously designed to be presented to the people of the South, each as parts of a whole. They are not ordinarily published together, nor are they even brought separately before the people whom it is most desirable they should reach, by any of the ordinary methods of publication.My suggestion is, that they be printed on linen, as handbills, to be posted and distributed by such means as are practicable among the people of the South wherever our armies and squadrons go. If freely issued in this comparatively permanent form, they would be conveyed to distant points as a matter of curiosity by the whites; while the negroes would pass them from plantation to plantation, and thus many, both by accident, and by design, of the negroes, would come to the hands of the class of men whom it is so desirable, and now so difficult to reach. (I have turned a few leaves down, in the second volume, where you may find the class indicated to which I refer). Each would then become a centre of more correct rumors of the purposes and offers of the President; and a knowledge of the true designs of the government would thus be disseminated among those now so generally grossly deceived in this respect.14

Olmsted vacillated in his attitude toward President Lincoln. Olmsted reported one of his first impressions of President Lincoln: “He looked much younger than I had supposed, dressed in a cheap and nasty French black cloth suit just out of a tight carpet bag. Looked as if he would be an applicant for a Broadway squad policemanship, but a little too smart and careless. Turned and laughed familiarly at a joke upon himself which he overheard from my companion en passant.”15 Olmsted wrote a month later, “Lincoln has no element of dignity; no tact, not a spark of genius…He is an amiable, honest, good fellow. His cabinet is not that.”16 By October Olmsted’s opinion of the President had improved: “He appeared older, more settled (or a man of more character) than I had before thought. He was very awkward & ill at east in attitude, but spoke readily, with a good vocabulary, & with directness and point. Not elegantly. ‘I heerd of that’ he said, but it did not seem very wrong from him, & his frankness & courageous directness overcame all critical disposition.”17 When President Lincoln appointed Dr. William A. Hammond to be Surgeon General in April 1862, Olmsted wrote:”The President yesterday promised to nominate for Surgeon General, Hammond, the very man whom, eight months ago, we picked out as the best man in the corps for that office, and who, this having been discovered, has since been regarded as a rebel and rancorously hated accordingly….”18 Olmsted wrote a friend in September 1862: “The President is a poor whining broken-down idiot at such a time as this….”19

Olmsted also vacillated in his opinion of the contribution of women to the commission’s efforts. Initially skeptical of what he thought was the sentimental nature of women, he came to highly value their contribution to the health of Union soldiers.

Hard work had its effect on Olmsted, according to colleague George Templeton Strong, himself one of the Sanitary Commission’s most energetic members: “Olmsted’s letters indicate that excitement and hard work acting on a sensitive, nervous temperament are making his views morbid. He sees only present imbecility and future inevitable disaster. Seems to think the army a mere mob; War Department, paralyzed by corruption; Navy Department, ditto, and so forth.”20 Biographer Laura Wood Roper wrote of one missive: “The intemperate tone of Olmsted’s letter reflected not only his terrible anxiety but his ill health. Barely over jaundice, he was suffering from frequent and alarming attacks of vertigo; and he was so taut emotionally that at least once, on learning that the executive committee had rejected some proposal of his, he burst into tears in the office.”21

These outbursts had a price. Even Strong’s confidence in Olmsted was not unshakeable. Only five weeks later, Strong wrote: “Olmsted is in an unhappy, sick, sore mental state. Seems trying to pick a quarrel with the Executive Committee. Perhaps his most insanitary habits of life make him morally morbid. He works like a dog all day and sits up nearly all night, doesn’t go home to his family (now established in Washington) for five days and nights together, works with steady, feverish intensity till four in the morning, sleeps on a sofa in his clothes, and breakfasts on strong coffee and pickles!!!”22 He lamented to his diary: “It will be a terrible blow to the Commission if we have to throw Olmsted over. We could hardly replace him.”23

As Olmsted assumed more authority, Strong grew more worried, writing on March 5, 1863: “Olmsted is unconsciously working to make himself the Commission. “Perhaps he is competent to do all the work of the commission without advice or assistance. If so, I for one am inclined to withdraw and let him have all the credit of doing it.”24 Less than a week later, Strong wrote: “I fear Olmsted is mismanaging our Sanitary Commission affairs. He is an extraordinary fellow, decidedly the most remarkable specimen of human nature with whom I have ever been brought into close relations. Talent and energy most rare; absolute purity and disinterestedness. Prominent defects, a monomania for system and organization on paper (elaborate, laboriously thought out, and generally impracticable), and appetite for power.”25

His monomania about the war’s success carried over into a proposal to form a Union League Club. Olmsted sought to rally loyal members of the upper class behind the Lincoln Administration and against Democratic leaders such as August Belmont and their European connections. By the spring of 1863, the Union League was in full operation.

A few months later, Olmsted resigned from the commission to become manager of the Mariposa gold mining project in California. The Mariposa job was arranged by former Tribune Managing Editor Charles A. Dana. Olmsted jumped at the chance. He felt he had lost the support of the Commission’s board and need to gain the financial security which the Mariposa job offered. “I think it has been decided again & again that I am not wanted…not in so many words, not in the logical & distinctly conscious conclusions of my friends, but in the deliberate vetoing — obstructing, condemning, upsetting and disusing all that I regard to be of any value in my work of the last two years,” Olmsted wrote Bellows. Bellows complained about Olmsted’s decision to move on: “I don’t know a half dozen men in the whole North, whose influence in the next five years I should think more critically important to the Nation.”26 It was a comment to one Bellows had made two years earlier when Olmsted had first talked of leaving: “I cannot hear of your leaving us under any circumstances for the present. The Commission would lose its chief hope of future usefulness.”27

The Mariposa Estate project failed, but Olmsted subsequently succeeded as the creator of public parks around the country.

Footnotes

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. li.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 280 (December 17, 1862).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 213.

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. xiii.

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 218 (Letter from Henry W. Bellows to John H. Heywood, March 10, 1863).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 165.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 543 (Letter to Winfield Scott, September 30, 1861).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 213.

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 175 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to Henry W. Bellows, September 29, 1861).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 189 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to Mary Cleveland Bryant Olmsted, July 2, 1861).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 169 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to John Olmsted, August 3, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Frederick L. Olmsted to Abraham Lincoln, September 30, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Frederick L. Olmstead to Preston King, July 9, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Alexander D. Bache to John G. Nicolay, July 11, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Frederick L. Olmsted to Abraham Lincoln, July 6, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to John G. Nicolay, October 10, 1862).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 189 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to Mary Cleveland Bryant Olmsted, October 19, 1861).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 189 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to John Olmsted, April 19, 1862).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 211 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to Charles Loring Brace, September 30, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 183 (September 30, 1861).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 211.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 290 (January 26, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 290 (January 26, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 303 (March 5, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 304 (March 11, 1863).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 236 (Letter from Henry W. Bellows to Frederick Law Olmsted , August 13, 1863).

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 189 (Letter from Henry W. Bellows to Frederick Law Olmsted, July 18, 1861).

Visit

Henry W. Bellows

Charles A. Dana (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John G. Nicolay (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

John G. Nicolay (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George Templeton Strong

Biography (www.newbedford.com)

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (www.nps.gov)

Olmsted’s Journeys (odur.let.rug.nl)