Without William H. Seward at the head of the Republican ticket, the direction of New York Republicans was unclear. Some Republicans like attorney David Dudley Field and editor Horace Greeley had grudges because they had been denied nomination to statewide office. Others like editor William Cullen Bryant and Judge John T. Hogeboom nurtured a moral disdain for Weed’s political tactics. Others like businessman Hiram Barney and attorney James A. Briggs were friends of Seward’s Senate rival, Salmon P. Chase. Even corruption divided the party. “The recent corrupt legislature at Albany must have had great weight with the Chicago Convention,” observed Harper’s Weekly. “It is in evidence that the most active agents of last winter’s corruption at Albany were also the most active friends of Mr. Seward’s at Chicago, and would presumably have been his most influential friends at Washington, in the event of his election. This consideration must have prevented many from giving him their support.”1

After the Republican National Convention in May, the feud between Thurlow Weed on one side and Horace Greeley intensified. Seward biographer Frederic Bancroft wrote: “It was on Weed that the blow fell with the greatest effect. He was so completely overcome that he lost his habitual prudence and stoical self-possession, and gave way, at first, to angry words and tears. No wonder, for his ambition, his affections, and his reputation as a party manager were involved. He had fondly hoped to crown the presidency a political devotion that had begun more than thirty years before, when Seward was a young and shy anti-Mason. [Henry J.] Raymond had much less at stake politically; but, as Seward’s spokesman in metropolitan journalism, he and his newspaper were put at a great disadvantage by a result that would give much prestige to Greeley and the Tribune. As Weed and Raymond could see no mistake in their management, they naturally blamed Greeley for their misfortunes. And they were especially angered by these exultant sentences: ‘The past is dead. Let the dead past bury it, and let the mourners, if they will, go about the streets.”2

According to Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen: “Weed declared that Greeley, a disappointed office seeker, had intrigued against Seward simply for revenge. Greeley asserted that Seward had been killed by Albany corruption. His break with Weed and Seward, said the Tribune‘s editor, was due to his dislike of their principles. He feared that, in consequence of their domination, the Republican party would ‘become rotten before it was ripe.”3 Harper’s Weeklyobserved: “Hitherto Mr. Greeley has been generally considered by his friends as an ardent and conscientious man, who rose above petty considerations of personal spite and personal aggrandizement; the true story of his desertion of Seward will, doubtless, confirm this impression, and will show that in his action at Chicago he rather played the part of Brutus than that of Judas.”4

Greeley biographer Ralph Fahrney wrote: “The general effect of the Chicago episode was to enhance the political fortunes of the one now credited quite generally with having slaughtered Seward. Greeley was expected to exert considerable influence with the incoming administration at Washington. One cartoon depicted him bearing the new President into the White House on his shoulders, and there were rumors afloat that he would be the next postmaster-general. Such preferment, added to the effectiveness with which the Tribune advocate had coöperated with the ‘conservatives’ at Chicago to dispatch Seward, aroused the bitterest hostility on the part of the Weed faction.”5

Other journalists piled into the dispute. Historian Reinhard Luthin wrote: “For a period following the Chicago convention the New York Republicans were sharply divided into the Seward-Weed faction and the anti-Weed or former Free Soil Democratic faction led by William Cullen Bryant, Horace Greeley cooperated with the latter wing. The pro-Seward Henry J. Raymond, editor of the New York Times, charged that Greeley was largely responsible for blocking Seward’s nomination; he declared that some six years previous the Tribune editor had written a letter to Seward ….”6The letter broke up a two-decade political partnership that had begun in 1834 when Weed and Seward arranged for Greeley to edit and publish a campaign newspaper, The Jeffersonian.

Seward biographer Frederic Bancroft wrote: “To understand the magnitude of the sensation that the three great Republicans editors…created, the reader must remember that the general public had never heard anything definite about Greeley’s angry complaints of 1854. Doubtless to cover up his own lack of precaution, and to give Greeley’s offense as heinous a color as possible, Weed said that he had ‘remained for six years in blissful ignorance of its [the letter’s] contents,’ and he implied that Greeley’s hostility had been insidious and revengeful.” In an open letter, dated in Auburn, and doubtless written with Seward’s full knowledge, Raymond charged Greeley with being the chief cause of Seward’s defeat, and with having plotted it in a way that was both deceitful and dishonorable.” Announcing what had taken place six years before, he declared that Greeley in his recent acts was ‘deliberately wreaking the long-hoarded revenge of a disappointed office-seeker.’ Raymond’s letter was full of the thorns of sarcasm, and was almost as resentful and imprudent as Greeley’s of 1854.”7

Historian Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “Raymond’s attack filled Greeley with fury, all the more because there was in it an element of truth. As he himself admitted, during the past six years his relations with the Senator ‘had always been frank and kindly.’ He had breakfasted and dined at Seward’s home and mutual friends had understood him to say that he was a Seward supporter. Furthermore he had complained in the famous letter that he was passed by in patronage distribution. Now he began calling for that document, declaring that Seward withheld it so that his devotees could pervert it to their purposes.”8

Noted Greeley biographer Jeter Allen Isely, “As good a newspaperman — and poor a controversialist — as Raymond should never have slugged it out with Greeley in the editorial ring. But the Times persevered, assisted by Webb’sCourier and Enquirer. Soon, both Raymond and Webb were so dazed that they were hitting one another. The Tribuneeditor retired to a corner and beamed as he pointed to their contradictions and to Webb’s public admission that the Sewardites had attempted to undermine Greeley’s influence by insinuations against his character.”9 Calling Greeley a “viper,” Webb had charged that “a more deliberate and wicked falsehood than this never found publicity, even through the columns of the Tribune…It was under the garb of friendship that the viper struck the blow; it was as the long-tried and well known friend of Seward, shedding crocodile tears over his unavailability, that he [Greeley] poisoned the minds of the leading men in the Convention and created doubts in regard to Mr. Seward’s strength…”10 With feuding friends like these, Mr. Lincoln didn’t need enemies in New York.

Historian Luthin wrote: “The wrangling was interrupted to hold a monster Lincoln-Hamlin ratification meeting in Cooper Institute on June 7. The ‘angel’ of the Weed organization, Richard M. Blatchford, presided — and cheers were given in turn for Seward and Greeley. In late August the Republicans met in convention at Syracuse and reiterated that the hatchet had been buried for the duration. The pro-Weed Governor Edwin D. Morgan and the anti-Weed Lieutenant Governor Robert D. Campbell were renominated. Presidential electors were chosen representing the different groups. A week later a new Republican State Central Committee was organized at Albany — with the pro-Weed Simeon Draper as chairman and the anti-Weed leader, George Opdyke, as a member. A vigorous campaign was mapped. The Republicans were out for victory.”11

Two of Mr. Lincoln’s top political strategists and fellow lawyers, David Davis and Leonard Swett, formed an alliance of convenience with Thurlow Weed in the months after the Republican Convention. Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen: “On August 18 Davis appeared in Albany, and he and Weed went on from there to Saratoga. Swett and Simon Cameron may have rendezvoused there with them. There is some evidence that the four men agreed to act together in controlling Lincoln’s administration, and in opposing the ambitions of Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, who was close to Bryant, Opdyke, Field and other anti-Weed Republicans in New York State. Whether or not a bargain was struck then and there, they worked in harmony during the great part of the campaign.”12

Thus, Mr. Lincoln’s top Whig supporters aligned with the Whig wing of New York Republicans — for political and business interests. Former Democrats now in the Republican Party like Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull had kindred spirits among the anti-Seward Democrats like David Dudley Field and William Cullen Bryant. Fortunately for the Republicans, New York Democrats were even more fractured.

Meanwhile, the Democrats were divided into three camps — the Douglas ticket, the Lane ticket and the Bell ticket. “It gives me great pleasure to say that political affairs are working kindly in this State,” Governor Edwin D. Morgan wrote Mr. Lincoln in “I am now of the opinion, there will be a ticket for Breckingridge & Lane in this State fairly supported. If so, we shall have no serous difficulty here. There should be and there will be no pains spared to carry the State, and it will be carried by a handsome majority.”13 By the end of August, Morgan was less sanguine: “The Breckinridge men yesterday made proposals for a union on the election ticket (Breckenridge & Douglas). It was a proposal from the Breckenridge men that could not be accepted by the Douglas men and made on the former’s supposition that Mr Douglas was too weak to accomplish anything, even the carrying of a single state. The friends of Douglas are raising considerable money and will yet try various expedients to accomplish something in this State. But all will fail. We shall beat them as they are, we shall beat them if they unite. In the latter event by not less than 40000.”14

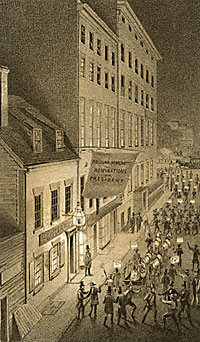

When the New York Democrats did eventually unite, it was too late. The Republicans had the momentum. On September 13, Attorney George Templeton Strong watched a “grand procession of the ‘Wide-Awakes,’ a new notable club of organization of the Republicans. It extends through these Northern states, is semi-military, and is intended as people say) to keep order at Lincoln’s inauguration (he will certainly be elected) in case Governor Wise and Mr. Yancey and other foolish Southern demagogues try to make a disturbance. This procession, which we watch in Astor Place and the Bowery, was imposing and splendid. The clubs marched in good order, each man with his torch or lamp of kerosene oil on a pole, with a flag below the light; and the line was further illuminated by the most lavish pyrotechnics. Every file had its rockets and its Roman candles, and the procession moved along under a galaxy of fire balls — white, red, and green. I have never seen so beautiful a spectacle on any political turnout.”15 The featured speaker was German-American Carl Schurz of Wisconsin.

The next night, Strong wrote that “Last night’s Republican turnout is the town talk. Everyone speaks of the good order and the earnest aspect of the ‘Wide-Awakes,’ and likes this to the ‘Tippecanoe and Tyler too’ gatherings of 1840. Certainly, all the vigor and enthusiasm of this campaign are thus far confined to the Republicans. Their adversaries are disorganized, divided, and discouraged.”16 Historian Reinhard H. Luthin wrote:

All that manufactured noise, simulated enthusiasm, and fanfare cost money. Speakers had to be paid, too, and newspaper subsidized. It was not surprising that the crinkling of campaign dollars was audible behind the scenes. Judge David Davis appealed to Thurlow Weed to raise more, and ever more, funds, commenting in underscored words: ‘Men work better with money in hand.”That task of collecting the currency sinews of party warfare was undertaken mainly by Governor Edwin D. Morgan of New York, Republican National Chairman and a money-laden merchant, and [New Hampshire’s George G.] Fogg. The affluent Morgan borrowed $20,000 for the campaign on his own collateral.Seward’s banker-friend, Richard M. Blatchford of New York, generously opened his checkbook, reminding the party powers after the election, “Mr. Weed tells me the $3,000 which I advanced in one sum last October was sent by him to Mr. Lincoln’s relative Mr. Smith at Mr. Lincoln’s suggestion for the purpose of carrying the Legislature of Illinois which was deemed in danger.”17

Meanwhile, Douglas came to Manhattan and was feted at a meeting of 30,000 New Yorkers, according to Leo Hershkowitz in Tweed’s New York. “The Illinois senator arrived shortly after two [o’clock] to cheering crowds and the playing of ‘Hail, Columbia.’ August Belmont was chairman of the barbecue meeting, and a whole group of the usual faithful, [Peter] Sweeny, Connolly, Kelly and [William March] Tweed among them, were present. Belmont, Douglass [sic] and vice-presidential candidate Hirschel V. Johnson made speeches in support of themselves and party unity.”18

Historian Luthin wrote: “The Republicans continued to assail and ridicule their opponents’ incongruous coalition. They reminded naturalized Irish and German citizens of the former Know-No-thing records of the Constitutional Unionists. The Republicans were inspired with new vigor by the anti-Lincoln union. From upstate came reports of hostility and disgust on the part of both wings of the Democracy toward the ticket. Many Democratic votes were destined to be cast for Lincoln, some preferring Republicans to the opposing faction within their own party. The New York Herald, now an ardent advocate of anti-Lincoln fusion, asserted that there was no genuine union between the two Democratic wings and that the breach had widened since the October elections in Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Ohio. On October 16, [1860,] Dickinson, having reluctantly come to favor the fusion ticket, declared that he did so because it might make possible the choice of Breckinridge.”19

The determining factor in fusion was money. First, Douglas and Bell electoral lists were merged; the Breckinridge ticket resisted fusion, according to historian Stewart Mitchell, “to the bitter end, but the merchants and bankers of the city forced the union by promising money for the Democratic campaign only if it were effected. The ticket as finally completed represented Douglas, Bell, and Breckinridge in the proportion of 18, 10, and 7. The Tribune warned Republicans that rich Democrats were raising a fund of a million dollars, and Lincoln himself seems to have been disturbed at the news of the fusion.”20

“Although the great New York mercantile interests supported the anti-Lincoln ticket, the Republicans had the advantage of better organization. Weed in his day had few if any equals in the election craft. The Lincolnites also had better forensic talent. For many months they had been conducting a campaign of education at Cooper Institute, where meetings had been addressed by Lincoln himself, Frank Blair, Cassius M. Clay, and John Sherman. After the battle proper was joined other talent spell-binders were imported, among them Salmon P. Chase, Senator Doolittle, and Senator Henry Wilson. The popular Seward also took the stump in New York City and upstate.”21

Wisconsin Republican Carl Schurz was scheduled to speak at Cooper Institute — to deliver an extended critique of the policy of Senator Douglas. Schurz recalled: “On the evening of the meeting I dined with Governor Morgan, who was chairman of the Republican National Committee, and some prominent Republicans of New York, at the Astor House. On the way from the Astor House to the Cooper Institute, Governor Morgan, with whom I drove, asked me how long I expected to speak. I answered: ‘About two hours and a half.’ ‘Good heavens!’ exclaimed the Governor. ‘No New York audience will stand a speech as long as that!’ He seemed to be seriously alarmed. I explained to him that the speech I was prepared to make was a connected argument which I had to present to the public in its entirety or not at all, and that, therefore, if I could not be permitted to deliver the whole of it, some excuse must be found for my not speaking at all that evening. The Governor seemed much distressed. At last they submitted, but with the air of one who was resolved to meet an inevitable disaster with fortitude.”22 To Morgan’s relief, the speech was a success and many printed copies of it were distributed.

William Evarts’ biographer, Chester L. Barrows, wrote: “Evarts presided when Seward made his last speech of the campaign in the ballroom of the Palace Garden on Fourteenth Street. Some six thousand people had squeezed into the inadequate hall, while others surged about the entrance. Seward was late, and Evarts had an uncomfortable time allaying the impatience of the audience. He tried to introduce other speakers, but the crowd clamored for Seward. There were some shouts for Greeley, but Evarts would not heed them. Seward was finally greeted with a great ovation and delivered a spirited denunciation of the South. A spectator might well have believed that he was the candidate. At the close, the Wide-Awakes were on hand with torchlights to escort him to his hotel.”23

On October 28, George Templeton Strong wrote in his diary: “The talk today is that Fusionism may carry this state after all. Then the election goes into the House and would be long contested before a majority could united on any one of the three. Excitement would be prolonged and sectional fury intensified. I don’t feel like voting for Lincoln, but I should be sorry to see New York frightened into voting for anybody else, even if the inevitable crisis were thereby postponed to 1864.”24 A few days later, Strong wrote: “Think I will vote the Republican ticket next Tuesday. One vote is insignificant, but I want to be able to remember that I voted right at this grave crisis. The North must assert its rights, now, and take the consequences.”25

The Fusion efforts proved too little and too late. “Weed’s confidence remained undimmed,” wrote Historian Luthin, “when he received reports from the various precincts. ‘The fusion leaders have largely increased their fund,’ he wrote Lincoln as the fateful November day neared, ‘and they are now using money lavishly. This stimulates and to some extent inspires confidence, and all the confederates are at work. Some of our friends are nervous. But I have no fear of the result in this state.'”26 Thurlow Weed’s election eve orders in November 1860 read: “Close Up the Work of Preparation To-Night: Leave nothing for tomorrow but direct work. Pick out and station your men….Let there be an assigned place for every man, and, at sunrise, let every man be in his assigned place. Don’t wait until the last hour, to bring up delinquents. Consider every man a ‘delinquent who doesn’t vote before 10 o’clock. At That Hour Begin to Hunt Up Voters!”27 On November 1, Morgan had written Mr. Lincoln: All eyes and thoughts seem to be turned on New York. New York will not disappoint us. Her electoral ticket will have not less than 40,000 majority.”28

Morgan, as was his wont, was conservative. The Republican ticket took the state by more than 60,000 votes — sweeping both Morgan and Mr. Lincoln in office although they lost New York City by nearly a 2-1 margin. “Lincoln is elected,” wrote New York attorney Strong the day after the election on November 6. “Everybody seems glad of it.”29 Back in Illinois there was particular joy at the results in New York with its 35 electoral votes. Historian Reinhard H. Luthin wrote:

Republican presidential standard-bearer Lincoln himself was at the House of Representatives, along with State Auditor Jesse K. Dubois, Senator [Lyman] Trumbull, [Edward I.] Baker of the Illinois State Journal and other intimates.Then word came from New York! Lincoln’s electors had won that indispensable, vote-rich State! Trumbull’s friend, Henry McPike, described the scene when Lincoln and party received the despatch about the glad tidings from the Empire State:“Dubois jumped to his feet. ‘Hey,’ he shouted, and they began singing as loud as they could a campaign song, ‘Ain’t You Glad You Jined the Republicans?’“Lincoln got up and Trumbull and the rest of us. We were all excited. There were hurried congratulations. Suddenly old Jesse grabbed the despatch out of Ed Baker’s hand and started for the door. We followed…Lincoln last. The staircase was narrow and steep. We went down it still on the run. Dubois rushed across the street toward the meeting, so out of breath he couldn’t speak plain. All he could say was, ‘Spetch. Spetch.’ Lincoln, coolest of the lot, went home to tell his wife the news.”30

Footnotes

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 109 (Harper’s Weekly, June 2, 1860).

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 540.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 2576.

- Jeter Allen Isely, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 284-285.

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p. 63.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 210.

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 540-541.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 230.

- Jeter Allen Isely, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 319.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 65-66.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 210-211.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 256.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 112 (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Abraham Lincoln, July 9, 1860).

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 118 (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Abraham Lincoln, August 26, 1860).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 41 (September 13, 1860).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 41 (September 14, 1860).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 229.

- Leo Hershkowitz, Tweed’s New York: Another Look, p. 74 (Around this time, PeterSweeney changed his name to “Sweeny.”).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 217-218.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 218.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 217-218.

- Carl Schurz, The Autobiography of Carl Schurz, p. 166 (Abridgment by Wayne Andrews).

- Chester L. Barrows, William M. Evarts: Lawyer, Diplomat, Statesman, p. 95-96.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 55 (October 28, 1860).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 57 (November 2, 1860).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 218.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 218.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 118 (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Abraham Lincoln, November 1, 1860).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 60 (November 7, 1860).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 237.