Slow & steady wins the race

George B. McClellan seemed to lead a charmed life. “McClellan’s engaging personality, moreover, was not without its wonted effect, for it stirred the great heart in the White House to a feeling of friendliness quite apart from mere official support. We have seen something of the President’s amiable indulgence toward the statesmen who severally fancied that their names spelled the country’s salvation; but none of them, it is safe to say, were treated with such consideration as was shown, in the beginning, at least, to the ‘Young Napoleon.'” McClellan’s pretensions met with the utmost good humor. Flowers and invitations to dinner and kind words poured in upon him from the Executive Mansion, until even he, a very glutton for honor, turned aside to cry, ‘Enough!'”1

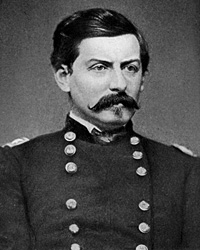

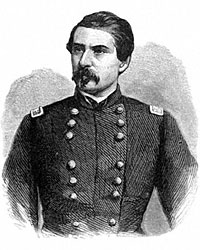

“General McClellan is indeed a striking figure, in spite of his shortness,” wrote presidential aide William O. Stoddard. “He is the impersonation of health and strength, and he is in the prime of early manhood. His uniform is faultless and his stars are brilliant, especially the middle one on each strap. His face is full of intelligence, of will-power, of self-assertion, and he, too, is in some respects a born leader of men. He has been admirably educated for such duties as are now upon him, and he has studied the science and art of war among European camps and forts and armies and battle-fields. He has vast stores of technical knowledge never to be acquired by any man among the backwoods, or on the prairies, or in law courts, or in political conventions. He can hardly conceal the clearness of his conviction that he ought not to be trammeled by any authority in human form that is by him supposed to be destitute of the essential training which he himself so fully possesses.”2

“Why, then, should he not confine his genius to army matters, and let Constitutional questions and politics and policies alone? He cannot. No American general ever did or could, and therein is the danger of the present situation,” wrote Stoddard.3 Because of McClellan’s vanity and sense of entitlement, he lacked the influence which more humility might have given him in the Lincoln Administration. McClellan believed he deserved glory. Anything less was an insult to his ego.

Unlike President Lincoln, McClellan was consumed by self-importance. Braggadocio was not in Mr. Lincoln’s vocabulary but it was in McClellan’s. After he took over as commander of the Army of the Potomac on July 27, 1861, he wrote his wife: “I find myself in a new & strange position here — Presdt, Cabinet, Genl Scott & all deferring to me — by some strange operation of magic I seem to have become the power of the land. I almost think that were I to win some small success now I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me — but nothing of that kind would please me — therefore I won’t be Dictator. Admirable self denial!”

McClellan deliberately sought and played a heroic role. But he also new have to motivate his soldiers. During the West Virginia campaign in June 1861, he addressed Union soldiers at Grafton: “Soldiers! I have heard that there was danger here. I have come to place myself at your head and to share it with you. I fear now but one thing — that you will not find foemen worthy of your steel. I know that I can rely upon you.”4 Nevertheless, Little Mac was better at rallying troops for field reviews than for battlefield attacks. And at critical moments in the Peninsula campaign, he was nowhere near the front. According to historian George H. Mayer, “McClellan’s rapid success was his undoing, for it revived hope that the Confederacy could be crushed in a single campaign. McClellan, however was a cautious man, and, when it became apparent in mid-autumn [1861] that he planned to postpone military operations until the following year, he lost the good will of the radicals. They remembered that McClellan was a Democrat and attributed his delay to pro-slavery sympathies. They were especially incensed by his policy of treating slaves as property and returning runaways to their owners.”5

The general Secretary of the United States Christian Commission, Frederick Law Olmsted, defended McClellan, writing: “He is a simple, stupid Christian, which is hardly the case with any other man of eminence. He is industrious, brave, patient. I cannot see that he has not accomplished all that could have been reasonably asked of him. I do not see where he has made a single great mistake. McClellan has from the first estimated the difficulties of overcoming the rebellion somewhat higher than most other men.”6

The big expectations which accompanied McClellan’s appointment to be commander of the Army of the Potomac in August 1861 and general-in-chief in November 1861. But McClellan’s slow progress in attacking Confederate positions also raised political doubts about him. McClellan’s problems can be seen in New York attorney George Templeton Strong’s diary comments about him:

- January 29, 1862: “The Demos begins to carp at McClellan, its idol six months ago.”7

- February 20, 1862: “The newspapers are goading McClellan, as they goaded [Winfield] Scott and [Irvin] McDowell last July. Heaven defend us from another premature advance and another Bull, or Bull-calf, run back again!”8

- April 9, 1862: “McClellan does not seem to get on very fast at Yorktown. But our weak spot just now is Norfolk, where the Merrimac, with her iron carapace, may do us infinite damage.”9

- April 12, 1862: “We are uneasy about McClellan. He is in a tight place, possibly in a trap, and the cabal against him at Washington may embarrass and weaken him. I am sorry to believe that [Irvin] McDowell is privy to it. He knows better, I am sure, but ambition tempts men fearfully.”10

- July 11, 1862: “The cause of the country does not happen to be thriving just now. McClellan’s army is safe, but how soon will the James River be closed by rebel batteries and supplies cut off?”11

- August 16, 1862: “An enterprising general, willing to risk something on prompt, vigorous offensive movements, might have carried it successfully through and taken Richmond — or he might not. But that is not McClellan’s style of work. He means to be safe, and is, therefore, obliged to be slow.”12

- August 19, 1862: “McClellan has gloriously evacuated Harrrison’s Landing and got safe back to where he was months ago. Magnificent strategy. But it has lost so many thousand men and millions of dollars.”13

- October 23: “McClellan’s repose is doubtless majestic, but if a couchant lion postpone his spring too long, people will begin wondering whether he is not a stuffed specimen after all.”14

McClellan alternated between depicting himself as a hero and as a martyr. His disdain for civilians oozes out in private correspondence but is also contained in official dispatches. The tone of his letters varies from abusive to unctuous. Unlike Mr. Lincoln, McClellan personalized everything. He had delusions of importance and grandeur. Biographer Stephen W. Sears wrote: “Each step of the process had become for him a uniquely personal achievement. ‘The Army of the Potomac is my army as much as any army ever belonged to the man that created it,’ he would say when looking back on his work.”15 McClellan’s paranoia was evident in a letter to Samuel L.M. Barlow at the end of July: “Yours of the 26 received. You are right to this extent at least — it has only been the fear of the effect upon my men, & partly perhaps of public opinion, that has prevented my being removed from the command of the Army of the Potomac. The command was for two days persistently pressed upon a General Officer [Ambrose Burnside], who happened to be a true friend of mine, & declined the offer. I know that the rascals will get rid of me as soon as they dare — they all know my opinion of them. There are aware that I have seen through their villainous schemes, & that if I succeed”.16

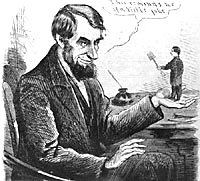

Presidential aide William O. Stoddard wrote in one of his anonymous newspaper dispatches: “The President’s visit to the army was a wise and well-advised action, and Mr. Lincoln has, no doubt, obtained from personal observation and friendly consultation with his favorite general, a far better and clearer idea of the position and capabilities of the army, than he could ever have done from the garbled and unfair reports of either the friends or the enemies of McClellan. The former, by the way, seem to be doing their uttermost to effect the ruin of their idol. They seem to take it for granted that all the world besides themselves are striving to do him harm, and by their frantic charges at every flag of any other color, they are fast transferring to him much ill feeling and distrust that they alone have merited. I do not harbor the idea, for one, that his many tempters will succeed in making McClellan anything else than an honest and loyal man, however woefully they may fail in creating a Napoleon. We need not look to him for anything like the Corsican’s Italian Campaign, but at the same time we need fear no burlesque attempt at a coup d’etat.”17 But another presidential aide, John Hay, reflected White House frustration when he wrote: “The little Napoleon sits trembling before the handful of men at Yorktown afraid either to fight or run. Stanton feels devilish about it.”18

Radical Republicans and northern newspapers lost patience with McClellan. Ralph R. Fahrney, biographer of Horace Greeley, wrote that Greeley’s Tribune “lost no opportunity to undermine public confidence in the ‘young Napoleon,’ sedulously magnifying every rumor concerning curtailment of his authority as Commander-in-chief of the Union Armies, and finally virtually accusing him of hesitating to advance on Richmond upon reflection ‘that he would be likely to kill several thousand good voters’ whose support might be needed when he ran for President in 1864 under the banner of the ‘Sham Democracy.'”19

McClellan’s relations with the Lincoln Administration were further damaged in the summer of 1862 when he failed to move his army, which had been withdrawn from the Peninsula, to help General John Pope at the Battle of Bull Run. President Lincoln overruled his Cabinet and appointed McClellan to take charge of the disorganized defense of Washington and then to challenge the Confederate invasion of Maryland. The standoff at Battle of Antietam in mid-September partially restored General McClellan’s reputation although he failed to win the decisive victory that was within his grasp.

Relations between the President and the General deteriorated in the aftermath the battle. The Little Napoleon was enraged by the draft Emancipation Proclamation that was issued on September 22, 1862. Historian Joseph T. Glatthaar wrote: “No one in the administration had lauded him satisfactorily after his exploits, no one appreciated their significance, and now in the aftermath of his accomplishments Lincoln imposed abolitionism on the nation! ‘The Presdt’s late Proclamation, the continuation of Stanton and Halleck in office render it almost impossible for me to retain my commission & self respect at the same time,’ he commented disgustedly to his wife. ‘If I cannot make up my mind to fight for such an accursed doctrine as that of servile insurrection —- it is too infamous. Stanton is as great a villain as ever & Halleck as great a fool — he has no brains whatever.’ McClellan prepared a vigorous protest, and before submitting it he wisely called on comrades for comments. His friends convinced him not to send it. Instead, he issued a general order that reminded his troops of the relationship between soldiers and the government. ‘The remedy for political errors, if any are committed, is to be found only in the action of the people at the polls,’ he insisted.” 20

President Lincoln was not pleased with the Little Napoleon. According to his Civil War aides and eventual biographers, John G. Nicolay and John Hay, President Lincoln “had given McClellan everything he asked for, infusing his own indomitable spirit into all the details of work at the War Department and the headquarters of the army. It was by his order that McClellan had been pushed forward, that [Fitz-John] Porter had been detached from the defense of Washington, that the militia of Pennsylvania had been hurried down to the border. He did not share General McClellan’s illusion as to the monstrous number of the enemy opposed to him; and when he looked at the vast aggregate of the Army of the Potomac by the morning report on the 20th of September, which shows 93,149 present for duty, he could not but feel that the result was not commensurate with the efforts made and the resources employed.”21

Although President Lincoln repeatedly urged McClellan to follow up the Union victory at Antietam in September, McClellan showed no initiative. Mr. Lincoln visited McClellan’s army in early October. Nicolay and Hay wrote: “This vast multitude in arms was visited by the President in the first days of October. So far as he could see, it was a great army ready for any work that could be asked of it. During all his visit he urged, with as much energy as was consistent with his habitual courtesy, the necessity of an immediate employment of this force. McClellan met all his suggestions and entreaties with an amiable inertia, which deeply discouraged the President.”22 McClellan was instructed to move in orders written by General Henry Halleck and by the President himself, but he did nothing to respond, exhausting the President’s patience.

“There is no doubt that Mr. Lincoln’s regard and confidence, which had withstood so much from General McClellan, was giving way,” wrote Nicolay and Hay — undoubtedly reflected what had been the mood they observed at the White House. “The President had resisted in his behalf, for more than a year, the earnest and bitter opposition of the most powerful and trusted friends of the Administration. McClellan had hardly a supporter left among the Republican Senators, and few among the most prominent members of the majority in the House of Representatives. In the Cabinet there was the same unanimous hostility to the young general.”23

The President did not want to upset the 1862 elections — in which both military stagnation and the emancipation proclamation were major issues. “Lincoln was convinced at last that in addition to failing to crush [Confederate General Robert E.] Lee, McClellan as commander of the army was a threat to the survival of civil authority over the military. The last state election took place on November 5; the next day Lincoln directed Halleck to remove McClellan ‘forthwith, or as soon as he may deem proper,” wrote historians Benjamin Thomas and Harold M. Hyman. “McClellan and his soldiers took the dismissal with good grace, although there were a few spontaneous demonstrations. But only when [Secretary of War Edwin M.] Stanton felt sure there would be no trouble did he release the announcement to the press.”24

General McClellan was viewed as a potential Democratic candidate for President as early as the fall of 1861 when New York Democratic politicians like Samuel. L. M. Barlow started visiting him in Washington. Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “According to [Lincoln biographer Carl] Sandburg, McClellan’s interest in the Presidency dated from July 7, 1862, when he wrote his celebrated Harrison Landing letter to the Chief Executive. This letter may have been written with an eye to the Presidency, but if it was, McClellan showed a surprising lack of interest in politics until later in 1863. The General kept aloof from political currents until October of that year, when he wrote a letter to Charles Biddle endorsing the candidacy of Judge George W. Woodward for the governorship of Pennsylvania. ‘Little Mac’ intended his letter only as a personal gesture, but actually it made him the popular candidate for the Democratic nomination.”

Zornow wrote: “This letter, which placed McClellan squarely in the presidential race, was a restatement of his views of 1862. The policies expressed in both letters became the General’s personal platform during the campaign and won him the support of the majority of the Democratic party. He desired the war to continue till the Union was restored. He had no quarrel with the executive’s assuming more power during the struggle; in his Harrison Landing letter he had urged Lincoln to direct the entire civil and military policy of the country against the rebellion. The point where he and the Democrats parted company with Lincoln’s party was as to how that power was to be used. The Democrats insisted that there should be no interference with slavery, no arbitrary arrests, no martial law in pacific areas, no confiscation, and no punitive measures against the vanquished. These were the essential planks in the conservative Democrats’ platform as well as McClellan’s.25 In his letter, McClellan wrote to President Lincoln:

You have been fully informed, that the Rebel army is in our front, with the purpose of overwhelming us by attacking our positions or reducing us by blocking our river communications. I can not but regard our condition as critical and I earnestly desire, in view of possible contingencies, to lay before your Excellency, for your private consideration, my general views concerning the state of the rebellion; although they do not strictly relate to the situation of this Army or strictly come within the scope of my official duties. These views amount to convictions and are deeply impressed upon my mind and heart.

Our cause must never be abandoned; it is the cause of free institutions and self government. The Constitution and the Union must be preserved, whatever may be the cost in time, treasure and blood. If secession is successful, other dissolutions are clearly to be seen in the future. Let neither military disaster, political faction or foreign war shake your settled purpose to enforce the equal operation of the laws of the United States upon the people of every state.

The time has come when the Government must determine upon a civil and military policy, covering the whole ground of our national trouble. The responsibility of determining, declaring and supporting such civil and military policy and of directing the whole course of national affairs in regard to the rebellion, must now be assumed and exercised by you or our cause will be lost. The Constitution gives you power sufficient even for the present terrible exigency.

This rebellion has assumed the character of a War: as such it should be regarded; and it should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian Civilization. It should not be a War looking to the subjugation of the people of any state, in any event. It should not be, at all, a War upon population; but against armed forces and political organizations. Neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of states or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment. In prosecuting the War, all private property and unarmed persons should be strictly protected; subject only to the necessities of military operations. All private property taken for military use should be paid for or receipted for; pillage and waste should be treated as high crimes; all unnecessary trespass sternly prohibited; and offensive demeanor by the military towards citizens promptly rebuked. Military arrests should not be tolerated, except in places where active hostilities exist; and oaths not required by enactments Constitutionally made should be neither demanded nor received. Military government should be confined to the preservation of public order and the protection of political rights.

Military power should not be allowed to interfere with the relations of servitude, either by supporting or impairing the authority of the master; except for repressing disorder as in other cases. Slaves contraband under the Act of Congress, seeking military protection, should receive it. The right of the Government to appropriate permanently to its own service claims to slave labor should be asserted and the right of the owner to compensation therefore should be recognized. This principle might be extended upon grounds of military necessity and security to all the slaves within a particular state; thus working manumission in such [a] state and in Missouri, perhaps in Western Virginia also and possibly even in Maryland the expediency of such a military measure is only a question of time. A system of policy thus constitutional and conservative, and pervaded by the influences of Christianity and freedom, would receive the support of almost all truly loyal men, would deeply impress the rebel masses and all foreign nations, and it might be humbly hoped that it would commend itself to the favor of the Almighty. Unless the principles governing the further conduct of our struggle shall be made known and approved, the effort to obtain requisite forces will be almost hopeless. A declaration of radical views, especially upon slavery, will rapidly disintegrate our present Armies.

The policy of the Government must be supported by concentrations of military power. The national forces should not be dispersed in expeditions, posts of occupation and numerous Armies; but should be mainly collected into masses and brought to bear upon the Armies of the Confederate States; those Armies thoroughly defeated, the political structure which they support would soon cease to exist.

In carrying out any system of policy which you may form, you will require a Commander in Chief of the Army; one who possesses your confidence, understands your views and who is competent to execute your orders by directing the military forces of the Nation to the accomplishment of the objects by you proposed. I do not ask that place for myself. I am willing to serve you in such position as you may assign me and I will do so as faithfully as ever subordinate served superior.

I may be on the brink of eternity and as I hope forgiveness from my maker I have written this letter with sincerity towards you and from love of my country.26

Two years later, at the end of September 1864, President Lincoln related to aide John Hay a complicated story of Congressman Fernando Wood’s visits to General McClellan in the fall of 1862. Mr. Lincoln said that McClellan and General William F. “Baldy” Smith had been intimate friends until “one day Fernando Wood and one other politician from New York appeared in Camp & passed some days with McClellan. From the day that this took place, Smith saw or thought he saw that McClellan was treated him with unusual coolness & reserve. After a little while he mentioned this to McC. who after some talk told Baldy he had something to show him. He told him that these people who had recently visited him, had been urging him to stand as an opposition candidate for President: that he had thought the thing over, and had concluded to accept their propositions & had written them a letter (which he had not yet sent) giving his idea of the proper way of conducting the war, so as to conciliate and impress the people of the South with the idea that our armies were intended merely to execute the laws and protect their property &*c., & pledging himself to conduct the war in that inefficient conciliatory style. This letter he read to Baldy, who after the reading was finished said earnestly ‘General, do you not see that looks like treason: & that it will ruin you and all of us.’ After some further talk the General destroyed the letter in Baldy’s presence, and thanked him heartily for his frank & friendly counsel. After this he was again taken into the intimate confidence of McClellan. Immediately after the battle of Antietam[,] Wood & his familiar came again & saw the General, and again Baldy saw an immediate estrangement on the part of McClellan. He seemed to be anxious to get his intimate friends out of the way and to avoid opportunities of private conversation with them. Baldy he particularly kept employed on reconnoisaances [sic] and such work. One night Smith was returning from some duty he had been performing & seeing a light in McClellan’s tent he went in to report. Several persons were there. He reported & was about to withdraw when the General requested him to remain. After every one was gone[,] he told him those men had been there again and had renewed their proposition about the Presidency — that this time he had agreed to their proposition and had written them a letter acceding to their terms and pledging himself to carry on the war in the sense already indicated. This letter he read then and there to Baldy Smith.” 27

Historian James G. Randall defended McClellan against these allegations: “It is to be noted that this story was used by Thurlow Weed to ruin McClellan in the presidential campaign of 1864. The tale is very indirect; it comes from General [William F.] Smith to Governor [ J. Gregory] Smith, then to Lincoln, and through John Hay to the reader. Whatever may have passed between Fernando Wood and the general, there was nothing in McClellan’s actual conduct which showed anything like treachery against the Union or any deep-laid intrigue against Lincoln.”28 Feelings in the Lincoln Administration had long been unkind to McClellan. “As his political prominence increased, Secretary Stanton’s animosity grew apace,” wrote biographer Sears. “Stanton operated by his rule that any army officer (such as General McClellan) who played the sport of politics ‘must risk being gored.’ Once in that game, he could no longer ‘claim the procedural protections and immunities of the military profession.'”29

McClellan’s Democratic sympathies, particularly in the 1862 New York State gubernatorial election, came through in a mid-October letter to Samuel L. M. Barlow: “I am much obliged to you for [Democratic State Chairman John] Van Buren’s speech — which one of these days I hope to have leisure to read. I am rather glad to hear this morning that the democrats have carried Penna — the only trouble about their carrying N.Y. also may be in the rather ultra tone of Seymour’s first speech. If N.Y. goes democratic some of our dear friends in Wash[ington] will feel a little crest fallen. I must confess a double motive for desiring the defeat of [Republican gubernatorial candidates James S.] Wadsworth — I have so thorough a contempt for the man & regard him as such a vile traitorous miscreant that I do not wish to see the great state of N.Y. disgraced by having such a thing at its head.”30

General Wadsworth’s sins were unforgivable in McClellan’s eyes. As military governor of Washington, Wadsworth had confirmeded the fact that McClellan had failed to provide the level of troop protection for Washington that he had promised before moving the Army of the Potomac into position to attack Richmond. President Lincoln had approved McClellan’s military plans with a clear injunction that adequate troops must be left behind to protect Washington. McClellan wrote a memo in which he guaranteed that 70,000 troops were available. Wadsworth biographer Henry Greenleaf Pearson wrote that “with Lincoln, Stanton and Wadsworth jealously watchful of the departing commander, it was the final letter of McClellan’s…that confirmed their suspicions, and it was Wadsworth’s actions thereupon that set in operation the train of events which McClellan’s partisans later affirmed prevented him from capturing Richmond. On the morning of April 2, the day after McClellan’s departure, General Wadsworth appeared at the War Department with McClellan’s letter of the day before ordering him to detach four good regiments to the Army of the Potomac and to send four thousand men to Manassas. In his whole command, Wadsworth said, he had not that number of men in fit condition to take the field, and to that effect he had telegraphed the general commanding at Manassas. From Wadsworth’s indignant narrative Stanton received the full revelation of McClellan’s contemptuous ignorance and indifference in regard to provision for the safety of Washington.”31 Wadsworth wrote that he had only 19,022 soldiers available for duty around the Capital. “I deem it my duty to state that, looking at the numerical strength and character of the force under my command, it is, in my judgment, entirely inadequate to, and unfit for, the important duty to which it is assigned.”32

Just after Wadsworth was defeated in the 1862 gubernatorial campaign, McClellan was himself dismissed as commander of the Army of the Potomac. President Lincoln had run out of patience. McClellan biographer Stephen W. Sears wrote: “Initially assigned to Trenton, New Jersey, by the War Department, McClellan soon changed his posting to New York City. There, as his letters indicate, his associations were largely with leading figures in the Democratic party, among them Barlow, August Belmont, and the editors of the two leading Democratic newspapers, Manton M. Marble of the New York World and William C. Prime of the Journal of Commerce. One of the first visits, Governor-elect Horatio Seymour made in the fall of 1862 was to McClellan at Barlow’s New York mansion.

And, according to biographer William Starr Myers, “one of the first…gestures of friendliness came from the city government of New York, which was not only Democratic in party, but also somewhat tinged with that brand of it known as Copperhead. A resolution praising McClellan and inviting him to visit New York as the guest of the city was passed by the Board of Aldermen on November 15th and the Common Council on the 17th, and signed by the mayor on the 20th. McClellan replied in a clever and and shrewd manner on the 22nd of the month. He declined the invitation with warmest thanks and added: ‘I do not feel that it would be right for me to do so [accept hospitalities] while so many of my former comrades are enduring the privations of war and perhaps sacrificing their lives for our country.'”33

During the summer of 1863 the McClellans moved out of New York to a house on Orange Mountain in New Jersey, which would remain their residence until early 1865.”34 According to Sears, “In part this was an escape from the summer heat of the city, but it was also an escape from the growing pressures he was exposed to as a public figure.”35 McClellan’s supporters bought a house for the family at 22 West 31st Street and gave title to Mrs. McClellan.

Historian Sears wrote: “New York newspapers began to carry regular features headed ‘McClellan’s Movements’ listing his attendance at the theater and the opera and at dinner parties and grand balls. It was noticed that he was courted by Democrats of every station. New York’s newly elected governor, Horatio Seymour, arranged to confer with him, as did August Belmont, national chairman of the party, John Van Buren, state chairman, and Dean Richmond, a leading party strategist….He was seen regularly with such major corporate and financial figures — and party supporters — as Samuel Barlow, William Aspinwall, John Jacob Astor, and William B. Duncan….These men not only easily qualified as the ‘best people’ whose company McClellan had always favored, but their Democratic politics (like his) had a decidedly conservative cast.”36

Biographer William Starr Myers wrote that “much gossip and many rumors concerning McClellan were prevalent throughout the country, and his friends were well aware of them. The more balanced and judicious of his friends were of the opinion that he should do something to quiet the rumors and also retain his attitude of detachment from public affairs. This was sound advice, for still he held his military commission in the army and owed respect to his military superiors. His friend E. H. Eldredge of West Newton, Massachusetts, wrote to McClellan’s brother, Dr. J.H.B. McClellan in Philadelphia, warning against the General associating and appearing in public at the opera and on like occasions with John Van Buren, August Belmont, S.L.M. Barlow and other prominent Democrats.”37

Meanwhile, some conservatives tried to find another military command for McClellan. A Cooperstown Democrat, Samuel M. Shaw, wrote Thurlow Weed a letter which he forwarded to President Lincoln: “Not to be tedious: You can easily see that even the most loyal Democrats are sorely tried with the policy of the Administration on some important points. Opposed to the Confiscation bill, the Proclamation, &c, still do we falter for the Union? No! But we need some little help, which the Administration can easily give. If it would yield in one matter, it would strengthen our hands, & put a stop to much complaint. I know McClellan has your confidence & I need not tell you he has that of every loyal Democrat. We wish the President to give him some command I care not where. He would labor any where, even as Engineer at Vicksburg for Gen. Grant & there great talent is evidently needed. But let the President set him to work any where, and I assure you it will do great good in & out of the Army. Every army letter I get praises him; every man but the most bitter Radical regrets his absence from the Army. Why will the President hesitate to yield not to a party clique but to the People, in this matter? Just at this time, we “War Democrats” need a little aid from the Administration. Is it impossible for us to get it? Must we see our hands grow weak? The President has it in his power to electrify the men I act with, all over the North, by this one act, which calls for no change of policy the abandonment of no Radical measure. Cannot you aid in this matter?”38

Some Democratic politicians tried to maneuver a reluctant McClellan into an 1864 presidential candidacy while other politicians tried to maneuver McClellan out of the race. Francis P. Blair, father of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, wrote Barlow in early May 1864, trying to steer McClellan out of the campaign: “I believe if he would unbosom himself unreservedly & in confidence directly with the President that he would give him a military place in which he could be most useful…& in such even the political alliance in which he has to some extent been involved might be turned to the best possible account for the country.”39

Francis P. Blair, Sr., was persuaded by his son, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, to make another attempt to influence McClellan in a meeting at the Astor House on July 21. According to McClellan biographer William Starr Myers, “Through the good offices of S.L. M. Barlow a long and intimate conversation took place between Blair and McClellan. The latter evidently feared this whole movement was a trick to cheat him out of the nomination, and was noncommittal at the time. Blair began by telling McClellan clearly that he did not come from Lincoln, and that he had no authority or even consent to make any arrangements with him of any sort. He then urged McClellan, ‘with the privilege of age and long friendship,’ to have nothing to do with the approaching Chicago Democratic Convention. He told McClellan that if nominated for the Presidency he would be defeated. He urged him to ‘make himself the inspiring center and representative of the loyal Democrats of the North by writing a letter to Lincoln asking to be restored to service in the army, and declaring at the same time that he did not seek it with a view to recommend himself for the Presidential nomination. In case the President should refuse this request he would then be responsible for the consequences.'”40 In response, McClellan was noncommittal and Blair reported the non-response to President Lincoln. About nine weeks later, Blair reported that “The President neither expressed approval nor disapprobation…but his manner was as courteous and kind as General McClellan’s had been.”41

A few days later, President Lincoln — unaware of McClellan’s negative response — conferred with General Ulysses Grant about a possible army command for McClellan. “When the elder Blair learned of the meeting, he understood Lincoln and Grant had agreed that if the Democrats did not make the general their candidate, or if he took himself out of the running, ‘Gen. McClellan would be invited to return to the army.” Simon Cameron confirmed the story, named the president himself as his authority,” wrote historian Stephen Sears. “Nothing finally came of the matter.”42

In reply to Barlow, McClellan denied Blair’s insinuations “that while in command of the Army of the Potomac I entertained political aspirations and that my course was guided by them. In this he is entirely mistaken — my thoughts & time were devoted solely to the military affairs committed to me, and whatever political opinions I expressed were expressed officially & frankly to the Govt as a part of my duty as Comdr of the Army, or of one of the great armies of the nation. I never looked to the Presidency & no official or personal act letter or conversation of mine will bear a contrary interpretation. I deny that my course of conduct while in command was calculated to produce the impression that I was ready as a General to lend myself to any party to supplant the Chief Magistrate etc.”43

New York Times editor Henry J. Raymond saw a political opportunity. In early April 1864 Raymond wrote President Lincoln: “I am informed that a good many despatches sent by you to Gen. McClellan during his campaign have never been published, and that you are willing they should see the light. They would add greatly to the usefulness of the History of your Administration which I am compiling & I have, therefore, asked Mr. [William] Swinton, one of my associates in the Times, to call on you in regard to the matter &, if you assent, to procure copies of these despatches. Mr. S. is a gentleman of ability & intelligence and fully worthy of any confidence you may place in him.”44

Meanwhile, the Democratic National Convention was postponed from early July to late August in order to give them more power and flexibility. McClellan himself did not approve of the shift: “So the Convention is postponed! Probably I don’t know enough of the state of affairs to judge, but my instinct is against the movement, and I feel now perfectly free from any obligation to allow myself to be used as a candidate. It is very doubtful whether anything would induce me to consent to have my name used,” McClellan wrote New York World editor Manton Marble at the end of June.45

Friend Samuel L. M. Barlow wrote McClellan from the Chicago convention about the unanticipated problems he was encountering: “It is plain to me that but for [Dean] Richmond, [Samuel J.] Tilden and [Manton] Marble, the peace me, Lincoln men, and Seymour men, would have had it all their own way,” wrote Barlow on the eve of his nomination: He predicted that there would be a “wise platform.” McClellan replied on the evening of August 28: “Your messenger has just reached me. Much obliged for the trouble you have taken. Things are just as I would have them — if we win we win everything and are free as air. If we lose we lose like gentlemen. I would not for the world have given any power to make bargains. I will not come to town unless you send word to me that I must. If I am nominated I hope you will come out yourself as I shall want to talk to you about many things.”46

Barlow, McClellan’s campaign manager, had refused to go to Chicago early to manage the party platform. Worried about a possible threat by New York Governor Seymour, McClellan’s allies underestimated the competence of former Ohio Congressman Clement Vallandigham who inserted language in the platform that said “justice, humanity, liberty and the public welfare demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the States, or other peaceable means, to the end that at the earliest practicable moment peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union of the States.” McClellan’s allies lost a crucial subcommittee vote that would have made reunion a prerequisite for peace negotiations. They decided against contesting the platform at the level of either the full committee or full convention. As a consequence McClellan’s candidacy was torpedoed by the so-called “Peace Plank” in the Democratic National Platform:

Resolved that in the future as in the past, we will adhere with unswerving fidelity to the Union under the constitution as the only solid foundation of our strength, security, and a framework of government equally conducive to the welfare and prosperity of all the States both Northern and Southern.

Resolved that this Convention does explicitly declare, as the sense of the American people, that after four years of failure to restore the Union by [the experiment of] war, during which, under the pretence of a military necessity or war power higher than the Constitution, the Constitution has been disregarded in every part, and public liberty and private right alike trodden down, and the material prosperity of the country essentially impaired, justice, humanity, liberty and the public welfare demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities with a view to an ultimate convention of the States or other peaceable means to the end that at the earliest practicable moment peace may be restored upon the basis of the Federal Union of the States.47

Lincoln biographer Herbert Mitgang wrote “Nast’s most striking Civil War cartoon appeared in Harper’s on September 3, 1864. It was labeled ‘Compromise With the South,’ and it depicted a victorious Confederate soldier and mourning Northerners at a grave marked, ‘In memory of the Union heroes who fell in a useless war.’ At this period there was much sentiment in the North to thrust the blame for the continuing war on Lincoln and his party…. Nast’s cartoon was widely distributed to show that a vote for the Democrats would mean that all the blood and effort and ideal of the struggle would be lost. Nast’s cartoon was a forerunner of his still more important work to come exposing the corruption of the Tweed Ring and Tammany Hall.”48

It took a while for McClellan and his managers to compose a fitting acceptance of the nomination — time enough to elicit some subtle sarcasm from his Republican opponent about McClellan’s military skills. according to artist Francis B. Carpenter: “About two weeks after the Chicago Convention, the Rev. J. P. Thompson, of New York, called upon the President, in company with the Assistant Secretary of War, Mr. Dana. In the course of conversation, Dr. T. said: ‘What do you think, Mr. President, is the reason General McClellan does not reply to the letter from the Chicago Convention?’ ‘Oh!’ replied Mr. Lincoln, with a characteristic twinkle of the eye, ‘he is intrenching.'”49

But President Lincoln was worried, according to Pennsylvania journalist Alexander K. McClure: “Lincoln believed that McClellan, if elected, would be coerced into a policy of humiliating peace and the loss of all the great issues for which so much blood and treasure had been sacrificed. But that he ever cherished the semblance of resentment against McClellan, even when McClellan was offensively insubordinate as a military man and equally offensive in assuming to define the political policy of the administration, I do not for a moment believe. Had McClellan understood Lincoln half as well as Lincoln understood McClellan, there never would have been serious discord between them. It was the creation of what I believe to be McClellan’s entirely unwarranted distrust of Lincoln’s personal and official fidelity to him as a military commander, and that single error became a seething cauldron of woe to both of them and consuming misfortune to McClellan.”50

McClellan did entrench. He virtually declined to participate in the fall campaign . He wrote Barlow before the Democratic Convention: “I shan’t come again to N.Y. & don’t send to me any d-d politicians.”51 In early October McClellan wrote Charles Mason, the Washington manager of his campaign, “I have made up my mind on reflection that it would be better for me not to participate in person in the canvass.”52 McClellan wrote William C. Prime of theJournal of Commerce: “Don’t let Barlow telegraph for me unless it is absolutely necessary — my own judgment is that the few men I see the better, unless of the class of [John] Cisco etc. I can’t find any real use in seeing the politicians — rather the contrary.”

“McClellan was drawn out into public only three times as the campaign rolled along, the first time early in the canvass when his neighbors in Orange held a large demonstration of support. Crowds from as far away as New York City thronged into the town. Some 10,000 serenaded him, and he responded briefly. Later, in September, he showed himself at a rally in Newark,” wrote John Waugh in Reelecting Lincoln. “He was not seen again publicly for nearly two months, until a giant McClellan meeting in the streets of New York City on November 5, when for two and a half hours he silently reviewed his political army from the balcony of the Fifth Avenue Hotel.”53

After the 1864 election, McClellan resigned from the army and set sail for Europe. He wrote President Lincoln: “It would have been gratifying to me to have retired from the service with the knowledge that I still retained the approbation of your Excellency — as it is, I thank you for the confidence and kind feeling you once entertained for me, and which I am conscious of having justly forfeited….In severing my official connection with your Excellency, I pray that God may bless you, and so direct your counsels that you may succeed in restoring to this distracted land the inestimable boon of peace founded on the preservation of our Union and the mutual respect and sympathy of the now discordant and contending sections of our once happy country.” It was 14 years later that McClellan finally won election — as Governor of New Jersey.

Footnotes

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 119.

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 420.

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, Partners in Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War, p. 87.

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 146.

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln: Master of Men: A Study in Character, p. 335.

- William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 115-116.

- William O. Stoddard, Inside the White House in War Times, p. 116.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 84.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 97.

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 210.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 203 (January 29, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 208 (February 20, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 216 (April 9, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 217 (April 12, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 239 (July 11, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 246 (August 16, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 247 (August 19, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 267 (October 23, 1862).

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 110.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 376 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, July 30, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 112 (September 29, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 20 (April 9, 1862).

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p. 98-99 (New York Tribune, February 22, 1862).

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 175.

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 185.

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 225.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 123-124.

- Official Records of the Rebellion, series 1, vol. 2, part 2, p. 73-74 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Abraham Lincoln, Gen. George B. McClellan’s report of the operations of the Army of the Potomac from July 27, 1861, to November 9, 1862, www.civilwarhome.com/mcclellanchapter1.htm).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 231 (September 25, 1864).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume II, p. 122-123.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 356.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 561 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, October 17, 1862).

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 118.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 524.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 356.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 345.

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 423.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Samuel M. Shaw to Thurlow Weed, February 15, 1863).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 575 (Letter from Francis P. Blair to Samuel L. M. Barlow, May 1, 1864).

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 434.

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 434 (Letter from Francis P. Blair, Sr., National Intelligencer, October 5, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 366.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 574 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L. M. Barlow, May 3, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry J. Raymond to Abraham Lincoln, April 4, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 580 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Manton Marble, June 25, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 561 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, August 28, 1864).

- Mary Cortona Phelan, Manton Marble of the New York World, p. 39.

- Herbert Mitgang, The Fiery Trial: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 149-150.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 143.

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 225.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 586 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, August 8, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 609 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Charles Mason, October 3, 1864).

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 327-328.