Confederate agents planned a desperate act of terrorism in New York City for Election Day, 1864. Fortunately, their plot was aborted by good Union intelligence and bad Confederate planning. The plot had been hatched by Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Robert Martin, who wanted to disrupt elections by firebombing the city’s hotels. But when Martin and his Confederates arrived in New York City, they were chagrined to find that the city was overrun by Union troops sent there to guard again any rebel skullduggery. The Union general in charge was Benjamin Butler, whose harsh tactics while military governor in New Orleans had earned him the title “Beast Butler.” He was not a great field general but he was not a military governor to be trifled with. And Butler’s headquarters was in the Fifth Avenue Hotel, the same hotel where Martin and at least one of his lieutenants was staying.

During November 1864, New York City was targeted for more than once a terrorist attack by Confederate agents. The Lincoln administration knew about the plot because it had read communications being carried North by a Union double agent who regularly carried messages between Richmond and Canada — after first showing their contents to the War Department. It wasn’t the first time that a northern city had been targeted for terrorism. In August 1864, Confederate agents had planned with the Sons of Liberty for an attack on the Union prison at Camp Douglas outside Chicago — to release Confederate prisoners. These northern Copperhead movements had failed to provide the needed assistance and the plot collapsed. The same problem had afflicted the Confederate plot to disrupt the New York City elections nine weeks later. After that failure, the Confederate agents were prepared to act alone.

According to Duane Schultz in The Dahlgren Affair, “The sudden, massive presence of the Yankee soldiers dampened the martial ardor of the Sons of Liberty. Martin and [Lieutenant John] Headley learned the night before the scheduled assault that, indeed, the group’s enthusiasm and bravado had been squelched completely. The Copperheads canceled their convention. Captain [Emile] Longuemare, Martin’s contact with the Sons of Liberty, argued with their leaders, passionately making a case for continuing with the plan. The Sons of Liberty agreed to persevere, if they could postpone any action until Thanksgiving Day, but when that time neared, they cancelled again…At the last minute, they notified Martin that they would have no further connection with any attempt to create chaos in New York.”1

The reliability of the double agent’s information to set fire to multiple New York hotels was questioned — especially after Election Day passed peacefully. But General Benjamin Butler and thousands of Union troops had been mobilized to counter that threat. For General John A. Dix, commander of the Eastern Department based in New York City, this was merely the latest crisis he had to confront since taking his command immediately after the July 1863 Draft Riots. According to historian Charles J. Rosebault, “In New York General Dix was strongly inclined to believe this was a hoax, and John A. Kennedy, the Superintendent of Police, was of the same opinion. But the orders from the War Department had been peremptory, and on the day appointed for the attempt the military and the police were prepared to meet it.”2 The Lincoln Administration’s information was reliable, noted David Homer Bates, who worked in the War Department’s Telegraph Office:

…one of Thompson’s messengers who traveled between Canada and Richmond, was also in our secret service, and the War Department was therefore frequently advised of the plans of the conspirators. This man had reported that the rumor mentioned in Consul Jackson’s letter of November 1, 1864, of a purpose to set fire to certain Northern cities was correct, but that the work would not be attempted on Election Day, November 8, but several weeks later; and that due notice would be given by him when the actual date was fixed. Later advices indicated the week after Thanksgiving as the probable time. Nothing further, however, being received from our spy, Major [Thomas] Eckert went to New York on Thanksgiving Day, November 24, and on the following morning called on Major-General Dix, commanding the Department of the East, for a conference. The latter had already been advised by Secretary Stanton of the machinations of the Confederate commissioners and their emissaries, but was wholly incredulous of the news about the burning of the city.With the aid of the police department of the city Dix had already used every available means to track the conspirators, but without success, and the scheme appeared so diabolical that he concluded it was wholly imaginary. Eckert tried to convince him, but could not, that there was solid ground for the rumors, and that the danger was not only real but imminent. Superintendent Kennedy and Inspector Murray of the police department were called in conference, and they too proved to be unbelievers.Eckert therefore left them for the purpose of returning to his hotel to prepare a cipher-message to Secretary Stanton, asking for further instructions. Upon entering a Broadway omnibus, his eyes encountered those of our secret service man from Canada. Neither showed any recognition of the other, but when Eckert left the stage at the St. Nicholas Hotel the man also got out and followed him into the hotel and up-stairs to his room. All this time no word had been spoken by either. After the key was turned in the door, the man said that as there was not sufficient time to get the information to Washington by means of a New York ‘News‘ personal, the usual channel of communication, he had hurried from Toronto to New York to communicate to the War Department the fact that the conspirators intended to set fire to twelve or more New York hotels, whose names he gave, that very Friday evening. A lunch was ordered for the man, who was ravenously hungry and tired, having traveled for over twenty-four hours, and after his meal he was told to lie down, which he did, falling asleep almost instantly. Eckert locked him in and went back to Dix with his fresh confirmatory evidence, and both the military and civil authorities then accepted the situation and took immediate steps to thwart the plans of the conspirators. Plain-clothes men, policemen and soldiers by the hundred were quickly distributed about the city, with particular reference to the hotels that had been specially named by our spy as starting-points for the general conflagration.3

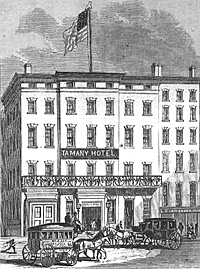

Early on the night of November 25, Martin met with his remaining Confederates, who had taken rooms in three New York City hotels. They were ordered to set these and 16 other hotels ablaze that night at 8 p.m. “Thirteen hotels were selected to be fired, they being the Astor, United States, Fifth Avenue, Everett, St. Nicholas, Lafarge, Howard, Hanford, Belmont, New England, St. James, Tammany and Metropolitan. Rooms in these hotels were taken by the members of the band, several of whom registered at two or more places. The plan they adopted, and which was carried out that evening, November 25, 1864, was as follows: At the hour agreed upon, or as soon after as possible, the party in each case placed his door-key in the keyhole on the outside, and then, after a suitable disposition of the bedding and furniture, started a fire by breaking a bottle of liquid having the qualities of Greek fire, and which had been prepared beforehand by one of the band familiar with that class of chemicals. In a few cases a clockwork device was the medium, set to go off within about an hour after being wound up. In either case the conspirator having completed his work left his room, locked his door, and disappeared. In addition to the fires at the hotels named there was an alarm in Barnum’s Museum, and two hay barges in the North River at the foot of Beach Street were also set on fire; but, fortunately, because of the activity of the military and civil authorities, who were so accurately informed in advance regarding the scheme, none of these dastardly attempts to cause a destructive conflagration proved successful. Had they all or even a majority of them succeeded, one’s imagination weakens in the effort to picture the awful loss of life and property that almost certainly would have resulted. Two reasons for the failure, both referring to traitors in their camp, are indicated in [Confederate Jacob] Thompson’s report to his principals (which will be quoted later), the first being a defect in the qualities of the Greek fire, and the other a premature disclosure of the plot to the Federal authorities by some one in the confidence of the Confederate commissioners. The second of these reasons had a real foundation, whatever may have been true of the other.4

Ironically, one of the fires was discovered by the Union double agent whose work had uncovered the plot. Staying over in New York City on his way to Canada, the spy smelled a fire which had been set in a nearby room. The Confederate plans went awry in another way. On December 3, 1864, confederate agent Jacob Thompson wrote Confederate Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin in which he laid out in his efforts to spread terror in New York and elsewhere: “Having nothing else on hand, Colonel Martin expressed a wish to organize a corps to burn New York city. He was allowed to do so and a most daring attempt has been made to fire that city, but their reliance on Greek fire has proved a misfortune. It cannot be relied on as an agent in such work. I have no faith whatever it and no attempt shall hereafter he made under my general directions with any such material….The attempt on New York has produced a great panic which will not subside at their bidding….”5

The city’s entire firefighting apparatus was engaged in fighting the hotel fires — and one that had been set in the P.T. Barnum Museum. David Homer Bates wrote: “For obvious reasons, General Dix requested the newspapers not to publish the names of suspected or arrested persons, but the following were, however, mentioned, the names, no doubt, being fictitious. At the Astor House, a man named Haynes; at the Howard, one named Horner; and at the Belmont a man who had registered as Lieut. Lewis, U.S.A. The New York Hotel Keepers’ Society offered a reward of $20,000 for the arrest and conviction of the miscreants; but while there were numerous arrests (including certain residents of the city), evidence sufficient to convict them could not be secured. Only one of the active conspirators was ever apprehended namely, Captain Robert C. Kennedy of the Confederate army, who had, with all the others, escaped to Canada, the day or day after the fires were started Kennedy returned to the United States in December, 1864, and was arrested in Cleveland, Ohio. His trial took place at Fort Lafayette, in New York harbor, under General Orders No. 14, dated January 17, 1865. The commission lasted twenty-three days and was presided over by Brigadier-General Fitz Henry Warren, and Kennedy was hanged on March 25, 1865.6

What Bates apparently did not know was that the leading Confederate conspirators narrowly escaped capture the day after the fires were set. They learned that Union officials knew all about their plot — and who was involved — as they were considering their plight over drinks at a Madison Square bar. The finished their drinks, lingered in New York for two another days, and later escaped to Canada.

“The attempt to set fire the city of New York is one of the greatest atrocities of age. There is nothing in the annals of barbarism which evinces greater vindictiveness,” concluded Bates. “In all the buildings fired, not only non-combatant men, but women and children, were congregated in large numbers, and nothing but the most diabolical spirit of revenge could have impelled the incendiaries to act so revoltingly.”7

Historian Shelby Foote wrote of the arson attempts: “Though the damage was minor, as it turned out, the possibilities were frightening enough. Federal authorities could see in the conspiracy a forecast of what might be expected in the months ahead, when the rebels grew still more desperate over increasing signs that their war could not be won on the field of battle.”8

Footnotes

- Duane Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, p. 229.

- Charles J. Rosebault, When Dana Was the Sun: A Story of Personal Journalism, p. 124.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, p. 299-300.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, p. 301-303.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, p. 305-306.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, p. 303-304.

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, p. 304.

- Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, Volume III, p. 725.