Presentation of 200 battle-flags to Governor Fenton at Albany, New York, July 4, 1865

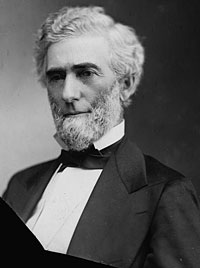

Reuben E. Fenton was “a suave and able businessman and politician of Old Democratic vintage, who came from western New York,” wrote historian Glyndon Van Deusen.”1 Fenton’s skills as a politician and speaker helped him rise quickly in Republican political ranks. “Fenton was a man without antipathies. He was a practical man, with an eye to material results. He wanted the crops to grow, the sun and rain in their seasons, and had about as much sentiment over political relations as a farmer over his barnyard,” wrote journalist John Russell Young. Republican political rival Roscoe Conkling said Fenton could “go around in his stockings during a heavy shower and dodge among the drops without wetting his feet”.2

Conkling biographer David M. Jordan was also deprecatory: “Fenton was a strange mixture of serious deficiencies and useful abilities. Men differed about him, to say the least. Consider these two statements, both by Republicans of similar political hue, both considered to be men of good will. Chauncey M. Depew of the New York Central Railroad: ‘He had every quality for political leadership, was a shrewd judge of character, and rarely made mistakes in the selection of his lieutenants.’ President Andrew D. White of Cornell: ‘There stood Fenton, marking the lowest point of the choice of State executive ever reached in our Commonwealth by the Republican party.'”3 Fenton was only the fourth Republican to run for Governor of New York and only the third to occupy the position so there wasn’t much basis for comparison.

Fenton’s political career was reaching its political zenith at the end of Mr. Lincoln’s life. Biographer Jordan wrote: “Even his closest friends never claimed that Fenton possessed any qualifications of the first order. What he did he have was a will to political power, a winning personality which enabled him to recruit and hold followers, a crafty but clever political instinct which usually kept him from making serious mistakes, and the good fortune to be elected governor of New York at about the same time that [Thurlow] Weed and [William H.] Seward sank into oblivion. The New York World called him ‘a weak man’; others said he was without ‘statesmanlike qualities’; the reality of the situation in 1867, however, was that Reuben E. Fenton was, regardless of merits or demerits, the number one leader of the New York Republican party.”4

He was a “suave and able businessman and politician of Old Democratic vintage, who came from western New York,” wrote historian Glyndon Van Deusen.5 “He had constantly courted the favor of Horace Greeley and, once he had been elected chief executive, proceeded to build up one of the smoothest political machines the state of New York has seen. He made a respectable governor and an acceptable senator, but he never enjoyed a personal or political popularity comparable to that of Horatio Seymour,” wrote Seymour’s biographer Stewart Mitchell.6 “Fenton was so adept at avoiding commitments that people were able to see what they wanted to see and in consequence he was cordially admired and vehemently despised. No one really knew him,” wrote biographer Helen Grace McMahon. “All sorts of stories were told about him by the hostile press — charges of arson, bribery, and embezzlement were printed — and yet no proof exists for any of these.”7

Fenton’s personality proved a useful asset in negotiating political problems with Mr. Lincoln. “My relations with President Lincoln were cordial. I was a member of the House of Representatives when he entered upon the duties of President and remained in the House until December, 1864, when I resigned my seat for the office of Governor of New York,” wrote Fenton in a memoir of his relations with Mr. Lincoln.8 Fenton, a strong supporter of President Lincoln’s war policies, served in House (1857-64) during the Civil War and in the Senate (1869-75) after the Civil War. His political career came into conflict with those of Roscoe Conkling and Edwin D. Morgan, and he failed to win the Republican nomination for Vice President in 1868. Although Fenton controlled the New York Republican Party during his gubernatorial terms, he lost that control in 1870 to fellow Senator Conkling.

Fenton recalled visiting President Lincoln with Indiana Congressman Schuyler Colfax in mid-December 1861 “to plan with him if need be, or better to say, to have his judgment as to a way of escape from the danger of an aroused hostile public sentiment which then seemed imminent.” Fenton later wrote:

Mr. Lincoln was keenly alive to the situation. The character and opinions of this rugged-featured and intellectually great man always enforced respect and confidence whatever the pleasantry of his manner. He said Providence, with favoring sky and earth, seemed to beckon the army on, but General [George B.] McClellan, he supposed, knew his business and had his reasons for disregarding these hints of Providence. “And,” said Mr. Lincoln, “as we have got to stand by the General, I think a good way to do it may be for Congress to take a recess for several weeks, and by the time you get together again, if McClellan is not off with the army, Providence is very likely to step in with hard roads and force us to say, the army can’t move.” He continued: “You know Dickens said of a certain man that if he would always follow his nose he would never stick fast in the mud. Well, when the rains set in it will be impossible for ever our eager and gallant soldiers to keep their noses so high that their feet will not stick in the clay mud of Old Virginia.” I have given very nearly the words of Mr. Lincoln. His felicity in stating a case and his good sense always impressed me, and my memory loses nothing in vividness with the lapse of years.9

“Much of Mr. Fenton’s time during the 37th Congress was spent in investigating frauds in the letting of contracts for war materials,” wrote Helen Grace McMahon. “Congress had passed a law a few months before the outbreak of the war requiring that all purchases of supplies and services except personal ones, in any department be made by advertising for bids unless there were a ‘public exigency.’ The investigating committee reported that in practice contracts were commonly let to favorites without bids, on the grounds of public exigency. The worst condition were in the Navy department and in the War department under secretary [Simon] Cameron.”10 Fenton’s concerns extended beyond Army contracts to Army soldiers and their welfare. According to Helen Grace McMahon, “In 1862 the New Yorkers in Washington formed the New York Soldiers’ Relief Association. Colonel Fenton was chairman of the preliminary meeting and was made president of the organization.”11

Fenton was an early convert to the Republican Party — and chaired its organizing convention in Syracuse in 1855. He also played an important role in 1864 in helping to sort out the factionalism of New York Republicans and to prepare for a Republican victory. Many more conservative Republicans were resigned to his nomination but unenthusiastic about it. In May 1864, Morgan wrote Thurlow Weed: “Fenton hopes to get the nomination for Governor, says their wing (the radicals!) will have it at any rate, claiming 9 out of 14 members of Congress for him. Let him have it — and any thing else he wants if thereby the public will be promoted.”12

“On the 22d day of August, I received a telegram from Mr. John G. Nicolay, Private Secretary, saying that the President desired to see me. I arrived in Washington next day. The President, speaking to me said, in language as nearly as I can remember: ‘You are to be nominated by our folks for Governor of your State. Seymour of course will be the Democratic nominee. You will have a hard fight. I am very desirous that you should win the battle. New York should be on our side by honest possession. There is some trouble among our folks over there, which we must try and manage. Or rather, there is one man who may give us trouble, because of his indifference, if in no other way. He has great influence, and his feelings may be reflected in many of his friends. We must have his counsel and cooperation if possible. This, in one sense, is more important to you than to me, I think, for I should rather expect to get on without New York, but you can’t. But in a larger sense than what is merely personal to myself, I am anxious for New York, and we must put our heads together and see if the matter can’t be fixed.”13 Fenton had not yet been nominated. He had been considered as a Republican candidate for governor in 1862, but the nomination had instead gone to a fellow Upstate radical, James S. Wadsworth.

The person about which Mr. Lincoln was worried was apparently New York political boss Thurlow Weed. New York Republican politics at that point in turmoil. Mr. Lincoln’s doubters — led by editors like William Cullen Bryant and Horace Greeley — were plotting to replace him. His supporters — led by the New York Times Henry J. Raymond — were convinced Lincoln was headed for defeat and urging him to begin peace negotiations with the Confederacy. In the midst of this crisis, Fenton said he was asked to sort out patronage problems in the New York Customs Office which another editor, the Albany Evening Journal‘s Weed, was upset about. Weed felt that the top officials “were unfriendly to him, and that he had no voice in those places of influence and power. Patronage had a welcome in the public service then. Removals and appointments were made upon the judgment or caprice of those at the head. The Republican convention in New York to place a candidate for Governor before the people was to come off early in September.”14

Fenton wrote: “As a result of this consultation with Mr. Lincoln, in the evening of the day after my arrival in Washington, Mr. Nicolay and I left for New York, and in Room No. 11, Astor House, next forenoon, I had a talk with Mr. Weed. I need not speak of the particulars of that conference. It is enough to say that Mr. Nicolay returned to Washington with the resignation of Mr. Rufus F. Andrews, and that Mr. Abram Wakeman — zealous friend of Mr. Weed — at once became his successor as Surveyor. From that time forward Mr. Weed was earnest and helpful in the canvass. The small majority in New York in November — less than 7,000 for the Republican electoral ticket — justified the anxiety of Mr. Lincoln, and serves to illustrate his political sagacity and tact. He was always politician as well as statesman.”15

Nicolay had arrived in New York on August 29 and wrote President Lincoln after meeting with Henry J. Raymond and Thurlow Weed and “several influential men from the country, who were in Mr. Raymond’s office when I went there. Raymond is still of opinion that the change contemplated should be made at once, although he does not seem to have conferred with any one, except Weed, who joins him very decidedly in the same belief. I myself asked Mr. Weed the distinct question whether the change ought to be made now, or after the election, and he answered, now by all means.” He concluded his letter: “I hope Fenton may come on tonight, as he thought he would, so that I may have his advice in the matter tomorrow.”16

The next day, Nicolay again wrote President Lincoln: “Mr Fenton arrived here this morning and had a conversation with Weed, in which he urged upon Weed his reasons in detail against any changes in the Custom House at this time. Mr. Weed heard him through, admitted there was much force in what he said; but was not convinced. In a conversation with me afterwards, Mr. Weed repeated what he said to me yesterday, that changes were absolutely necessary and would be productive of much good.”17 The changes that were made to placate Weed and unify the party for the benefit of Fenton and President Lincoln — even thought the persons nominated were not Fenton’s political allies.

In November 1864, Fenton defeated Governor Horatio Seymour by less than 8,000 votes. Fenton had received the Republican nomination despite the opposition of New York Republican boss Weed, who favored Union General John A . Dix, who commanded the Eastern District, headquartered in New York City. According to Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen, “Fenton seemed so strong that the Dictator did not even trouble to obtain a statement from the General that he would be willing to run. Weed later asserted that he had gone to Syracuse prepared to bow to the popular will, only to discover…that Fenton had no popular backing, and that Dix could have the nomination if he wanted it. Realizing that he had been ‘wooled,’ the old leader tried desperately to get in touch with Dix. At length word came back to see the latter’s note to Ward Hunt, a member of the convention. This note, in Weed’s judgment, would have ensured the General’s nomination, but before it could be obtained Fenton had captured the prize.”18

As Governor, Fenton came into conflict with the Lincoln Administration. “A few days after I succeeded to the office of Governor I was led to an investigation in regard to the quota of men for New York for the field, under the President’s call for 300,000 of December 19th just previous. My search led me to doubt the correctness of the assignment of quotas to several localities, and, as between several localities or districts, it was, to my mind, unequal and unjust. I do not mean it was so intended. It was a difficult and perplexing matter; differences in respect to methods were liable to arise and errors were likely to creep in. And, moreover, the total number, 61,000, for the State seemed to me clearly excessive. Thus impressed, accompanied by General George W. Palmer of my military staff, I went to Washington on the 21st of January.” The controversy had actually begun before Fenton took office, according to Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell:

On December 1, 1864, after having sent over 156,000 soldiers and sailors into the army and navy during the year, the state over which a so-called ‘Copperhead’ governor had presided since January 1, 1863, had an excess on credits with the federal government of 5,301 men, according to the report of the Republican who followed him in office. On December 19, 18164, Lincoln called for 300,000 troops, and about January 7, 1865, it was learned that the quota of New York would be 46,861. As soon as he had looked over the list of the men required of the thirty-one congressional districts Fenton found the assignments so unequal that he sent two of his aides to Washington to protest. One of these, Colonel George W. Palmer, left with Fry a careful explanation of the governor’s plan for the complicated business of crediting one and three-year enlistments properly to the several districts.

General Fry’s answer was a bombshell. On January 20 he telegraphed that revised quotas would be sent forward in a day or two, but that the quota of New York would be increased by the revision from 46,000 to over 60,000. Fenton took the first train to Washington in order to argue or wheedle a reduction out of Fry or Stanton. Not only was he unable to understand the war department’s use of figures, but the ‘large increase’ of the quotas in New York City seemed to him ‘extraordinary.’ When Fry sent on the corrected lists for the congressional districts on January 24, it was found that the six districts in New York and Brooklyn were called on for three and often four times as many men as the outlying districts. In talking with Fenton, General Fry laid the confusing inequalities and revisions to the carelessness of mustering officers and ignorance of the law on the part of the local officials.19

On January 26th 1865, Fenton wrote President Lincoln: “Honorable James A. Bell, George H. Andrews, Thomas B. Van Buren, and E. C. Topliff, Members of the Legislature, visit you in regard to filling the quotas for our State. They will represent to you the public feeling, and what we deem just cause for complaint. I beg you consider favorably what they may say; and allow me again to earnestly renew my recommendations as to the mode of filling the present quota”.20

Fenton himself met with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Provost Marshal General James B. Fry, but they were adamant about New York’s draft allocation. “Not doubting the right and justice of my claim for reduction and re-assignment as to the districts, I called on Mr. Lincoln. He gave me time and listened attentively and patiently to all I had to say. At the close he remarked, ‘I guess you have the best of it, and I must advise Stanton and Fry to ease up a little.’ He wrote upon a card to Mr. Stanton, and gave it to me to carry to him, as follows: “The Governor has a pretty good case. I feel sure he is more than half right. We don’t want him to feel cross and we in the wrong. Try and fix it with him.”21

Eventually, Fenton got the State’s quota reduced by 9,000 men. In the meantime, Fenton urged the postponement of the draft’s enforcement: “Do not press the draft. Think postponement three 3 or four 4 weeks would enable us to fill the quota. Give all the time that can possibly be allowed without detriment to the public service”.22 New York filled 34,000 of its quota with volunteers and 3,300 with conscripts.

Fenton’s frequent visits to the White House led him to be called on to open a White House serenade in November 1864. “After the [1864] election…just before I resigned my seat in Congress to enter upon my official duties as Governor at Albany, New Yorkers and others in Washington thought to honor me with a serenade. I was the guest of ex-Mayor Bowen. After the music and speaking usual upon such occasions, it was proposed to call on the President. I accompanied the committee in charge of the proceedings, followed by bands and a thousand people. It was full nine o’clock when we reached the Mansion. The President was taken by surprise, and said he ‘didn’t know just what he could say to satisfy the crowd and himself.’ Going from the library room down the stairs to portico front, he asked me to say a few words first, and give him if I could ‘a peg to hang on.’ It was just when General Sherman was en routefrom Atlanta to the sea, and we had no definite news as to his safety or whereabouts. After one or two sentences, rather commonplace, the President farther said he had no war news other than was known to all, and he supposed his ignorance in regard to General Sherman was the ignorance of all; that ‘we all knew where Sherman went in, but none of us knew where Sherman went in, but none of us knew where he would come out.’ This last remark was in the peculiarly quaint, happy manner of Mr. Lincoln, and created great applause. He immediately withdrew, saying he ‘had raised a good laugh and it was a good time for him to quit.’ In all he did not speak more than two minutes, and, as he afterward told me, because he had no time to think of much to say.”23

Greeley never came to Washington but the message about a potential Cabinet appointment was delivered by Hoskins. Fenton “had constantly courted the favor of Horace Greeley and, once he had been elected chief executive, proceeded to build up one of the smoothest political machines the state of New York has seen,” wrote historian Stewart Mitchell.24 In 1865, Horace Greeley “allied himself with Reuben E. Fenton of Chautauqua County, an anti-Weed Republican. Lincoln, disturbed by Greeley’s lack of support and even outright enmity, sought a way to lead Greeley back into the paths of righteousness, using Fenton as a contact,” wrote James M. Trietsch. President Lincoln suggested through an emissary that Greeley would be appointed Postmaster General after the 1864 election. Triestch wrote: “Fenton had for an active agent George G. Hoskins of Wyoming County, who kept in touch with Greeley. Finding the editor chilly, Hoskins so reported to Fenton, who was then in Congress, and Fenton advised the President. The outcome was a direct invitation asking for a meeting. Lincoln with his usual meekness, offering to make the trip to New York. In order to clarify matters, Lincoln wrote thus to Greeley

Dear Mr. Greeley:

I have been wanting to see you for several weeks, and if I could spare the time I should call upon you in New York. Perhaps you may be able to visit me. I shall be very glad to see you.25

Fenton was reelected Governor in 1866. Although he studied to be a lawyer, he instead started his professional life as a merchant and logger and ended it as a banker. Biographer David M. Jordan wrote: “Fenton’s two terms as governor were marked by several major reforms in education and in the administration of state hospitals and similar facilities. But Fenton was not an outstanding speaker in a day when oratorical ability was considered one of the highest qualities in a public figure; he was a trimmer, who endeavored constantly to catch the drift of public feeling and adapt to it.”26

Footnotes

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 311.

- May D. Russell Young, editor, Men and Memories: Personal Reminiscences by John Russell Young, p. 215.

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 96.

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 97.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 311.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 376.

- Helen Grace McMahon, Reuben Eaton Fenton, p. 2.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 67 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 74-75 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Helen Grace McMahon, Reuben Eaton Fenton, p. 63-64.

- Helen Grace McMahon, Reuben Eaton Fenton, p. 67.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 200 (Letter from Edwin M. Morgan to Thurlow Weed, May 2, 1864).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 68-69 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 69 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 69-70 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 154 (Letter to President Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 155 (Letter to President Lincoln, August 30, 1864).

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 311.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 318-319.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Reuben E. Fenton to Abraham Lincoln, January 26, 1865).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 71-72 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Reuben E. Fenton to Abraham Lincoln, February 13, 1865).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 70-71 (Reuben E. Fenton).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 376.

- James M. Trietsch, The Printer and the Prince, p. 278-279.

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 97.