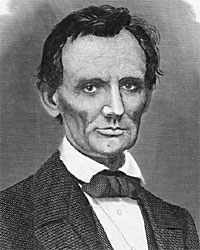

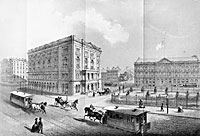

The Cooper Union speech which Abraham Lincoln delivered on February 27, 1860 “probably did more to secure his nomination, than any other act of his life,” wrote contemporary biographer Isaac Arnold, who was like Mr. Lincoln a prominent Illinois Republican. On the afternoon of the speech, Mr. Lincoln sat for a photographic portrait at the studio of Matthew Brady in New York. He later reputedly said, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.”1

The purpose of the trip east was two-fold — visit Mr. Lincoln’s son Robert at school in New England and test Mr. Lincoln’s political ideas and viability before a New York audience. George Haven Putnam wrote that “Years after the war, I heard from Robert Lincoln that his father had in January been planning to make a trip eastward to see the boy, who was then at Phillips-Exeter Academy. His father wrote to Robert that he had just won a case and that as soon as his client B. made payment he would arrange for a trip. A week or more later Lincoln wrote again to the boy, expressing his disappointment that the trip would have to be postponed.” Mr. Lincoln wrote that the client was broke and so was he. According to Putnam, “A week later Lincoln wrote again to his son, reporting that he was coming after all. ‘Some men in New York,’ he said, ‘have asked me to come to speak to them and have sent me money for the trip. I can manage the rest of the way.”2

The original invitation to speak in New York, however, arrived in Springfield in October. It came to invite Mr. Lincoln to participate in a lecture series at the Plymouth Church where famed preacher Henry Ward Beecher occupied the pulpit. By February, it was determined by both sponsors and speaker that a more political speech was called for. The sponsoring organization was changed, the location of the speech was changed and so was the political destiny of Abraham Lincoln. Until that point in his career, Mr. Lincoln had been little known in the East — except as the able opponent of Illinois Senator Stephen M. Douglas and the protagonist in the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates that helped define partisan policy differences over the extension of slavery to the territories.

“The Cooper Institute speech takes the plain principle that slavery is wrong, and draws the plain inference that it is idle to seek for common ground with men who say it is right,” wrote biographer Lord Charnwood. “Strange but tragically frequent examples show how rare it is for statesmen in time of crisis to grasp the essential truth so simply. It is creditable to the leading men of New York that they recognised a speech which just at that time urged this plain thing in sufficiently plain language as a very great speech, and had an inkling of great and simple qualities in the man who made it. It is not specially discreditable that very soon and for a long while part of them or of those who were influenced by their former prejudices in regard to Lincoln. When they saw him thrust by election managers into the Presidency, very few indeed of what might be called the better sort believed, or could easily learn, that his great qualities were great enough to compensate easily for the many things he lacked.”3

Footnotes

- Ralph E. Newman, Lincoln for the Ages, p. 139 (Johnson E. Fairchild, “Lincoln at the Cooper Union”).

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 257 (George Haven Putnam, Outlook of New York, February 8, 1922).

- Lord Charnwood, Abraham Lincoln, p. 156-157.