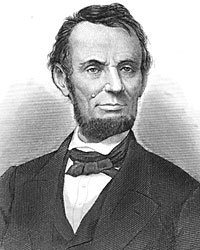

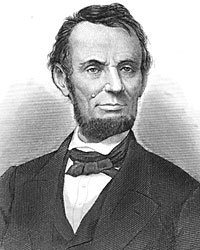

Abraham Lincoln

President-elect Receiving Visitors in Springfield

Lincoln and the Grip-Sack

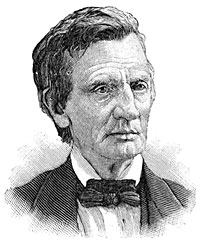

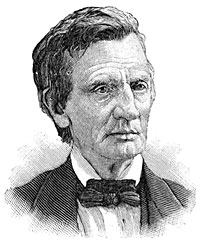

William M. Evarts

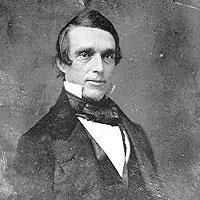

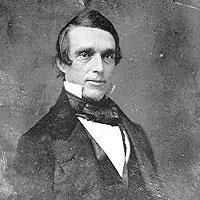

A. Oakey Hall

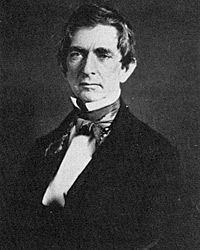

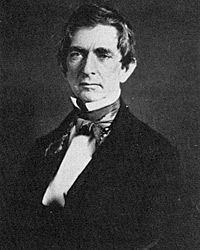

William H. Seward

Those Republicans opposed to New York Senator William H. Seward focused their fire on Seward ally Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania. Seward’s supporters focused their fire on Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase. According to historian Burton J. Hendrick: “The two most powerful Republican papers in New York City, the Tribune and the Evening Post, had joined hands in this twofold campaign to keep Seward and Cameron out of the administration and get Chase and [Gideon] Welles in. ‘Now I am even with Seward,’ Horace Greeley had exclaimed after the defeat of his enemy at the Chicago Convention, but his appetite for revenge had not been satiated. The motives of William Cullen Bryant, of theEvening Post, possibly had a more elevated character. The Evening Post represented the views of a faction which for years had been fighting the Seward-Weed machine as a corrupting force in the state. Cameron ranked second as an odious public character while their admiration for Chase knew no bounds.”1

Unlike Pennsylvania Republicans who concentrated their fire against their own Simon Cameron, New York Republicans concerned themselves with top patronage candidates from around the country. Cameron had wide support in Pennsylvania but weak support elsewhere. “Bryant’s fear about who would head the Treasury Department has increased when a report came out that Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania was the choice,” wrote Bryant biographer Charles Brown. “In some agitation, he answered Lincoln’s letter of January 3.”2 Bryant wrote:

I have this moment received your note[.] Nothing could be more fair or more satisfactory than the principle you lay down in regard to the formation of your council of official advisers. I shall always be convinced that whatever selection you make it will be made conscientiously.

The community here had been somewhat startled this morning by the positiveness with which a report had been circulated, reaching this city from Washington that Mr. Simon Cameron was to be placed in the Treasury Department. Forgive me if I state to you how we all should regard such an appointment— I believe I may speak for all parties, except perhaps some of the most corrupt in our own— The objection to Mr. Cameron would not be that he does not opinion hold such opinions as we approve, but that there is among all who have observed the course of our public men an utter, ancient and deep seated dullness of his integrity — whether financial or political. The announcement of his appointment, if made on any authority deserving of credit would diffuse a feeling almost like despair. I have no prejudices against Mr Cameron except such as arise from observing in what transactions he has been engaged as I have reason to suppose that whatever opinion had been formed respecting him in this part of the country has been formed on perfectly impartial and disinterested grounds. I pray you, again, to excuse this my giving you this trouble. Do not reply to this letter— Only let us have honest rigidly upright men in the departments — whatever may be their notions of public policy.3

According to Brown: “As a matter of fact, Lincoln had offered Cameron the post but on the same day that Bryant was writing him he notified Cameron that things had developed which made it impossible to take him into the cabinet. Lincoln did not want to recall the offer openly and asked Cameron to write declining the appointment as he had no objection to its being known that it was tendered.4 Bryant wrote President-elect Lincoln again on February 6, 1861:

I wrote to you yesterday in regard to the rumored intention of giving Mr. Simon Cameron, of Pennsylvania, a place in the Cabinet. I had not then spoken much with others of our party, but I have since heard the matter discussed, and the general feeling is one of consternation. Mr. Cameron has the reputation of being concerned in some of the worst intrigues of the Democratic party. His name suggests to every honest Republican in the State no other associations than these. At present, those who favor his appointment in this State are the men who last winter so shamefully corrupted our Legislature. If he is to have a place in the Cabinet at all, the Treasury department is the last of our public interests that ought to be committed to his hands.

In the last election, the Republican party did not strive simply for the control, but one of the great objects was to secure a pure and virtuous administration of the Government. In the first respect we have succeeded; but, if such men as Cameron are to form the Cabinet, we shall not have succeeded in the second.5

According to historian Brummer, “At the end of November, there was held in New York City a conference of prominent New York Republicans, mostly former [Democratic] Barnburners, the objects apparently being to further Chase’s chances and to discuss the subject of a New York appointment to the cabinet. Among those present were Lieutenant-Governor [Robert] Campbell, David Dudley Field, Charles A. Dana, William Curtis Noyes, George Opdyke, Hiram Barney, H. B. Stanton, Parke Godwin, and Thomas B. Carroll. This conference designated a committee to work for the ends mentioned above, and the committee subsequently held a consultation at Albany. At this time, it was so we find the anti-Weed faction in New York discussing the merits of Greeley, Field, Opdyke, Wadsworth, and Noyes.”

After Thurlow Weed returned east Bryant wrote Mr. Lincoln on December 25 to protest his influence: “The rumor having got abroad that you have been visited by a well known politician of New York who has a good deal to do with the stock market and who took with him a plan of compromise manufactured in Wall Street, it has occurred to me that you might like to be assured of the manner in which those Republicans who have no connections with Wall Street regard a compromise on the slavery question.” Bryant added that he hoped Mr. Lincoln’s Cabinet would include Republicans who had formerly been Democrats.6

President-elect Lincoln responded to Bryant on December 29: “The ‘well-known politician’ to whom I understand you to allude did write me, but [did] not press upon me any such compromise as you seem to suppose, or, in fact, any compromise at all. As to the matter of the cabinet, mentioned by you, I can only say I shall have a great deal of trouble, do the best I can. I promise you that I shall unselfishly try to deal fairly with all men and all shades of opinion among our friends.”7 The announcement that Seward would be appointed Secretary of State and the leak that Simon Cameron was headed for the Cabinet panicked the Bryant group.

Historian Elwin L. Page wrote: “Other prominent men came out against Cameron. Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts wrote to C.H. Ray that he was alarmed at the prospect of Cameron, and he authorized Ray to show the letter to Lincoln. Frank P. Blair wrote his son Frank on January 5, also authorizing his letter to go o Lincoln. He found ‘our friends’ in consternation. William Cullen Bryant, writing on January 3, was shocked. A week later he wrote Lincoln introducing George Opdyke, Judge J.T. Hogeboom, and Hiram Barney, representing the anti-corruptionists of New York, who were about to go to Springfield in the interests of Salmon P. Chase.8

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles later wrote: “At no time had his private judgment inclined the President to give Cameron the treasury. The intrigue of the New York clique and a few similar characters in Pennsylvania had, in some degree biased his mind, but sweeping condemnation on ever hand outside of the circle mentioned, convinced him his own instincts were right and that it would be an unacceptable if not improper appointment. Mr. Seward, who had trusted to his friends to accomplish his wishes, felt at length compelled to express his feelings and views. He stated to the President that association with Mr. Cameron would on many accounts make the appointment of that gentleman more pleasant to him than Mr. Chase, but dwelt strongly and more particularly on the understanding which existed and the disappointment which would follow if he discarded the Pennsylvania senator. On these points the President had arrived at conclusions entirely different, and Senator Preston King, whom, with others he consulted, while they had not a strong partiality for Mr. Chase, protested most earnestly against placing Cameron in the treasury.”9

President-elect Lincoln wrote Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull on January 7: “Gen. C. has not been offered the Treasury, and I think, will not be. It seems to me no only highly proper, but a necessity, that Gov. Chase shall take that place. His ability, firmness, and purity of character, produce the propriety; and that he alone can reconcile Mr. Bryant, and his class, to the appointment of Gov. S to the State Department produces the necessity. But then comes the danger that the protectionists of Pennsylvania will be dissatisfied; and, to clear this difficulty, Gen. C. must be brought to co-operate. He would readily do this for the War Department. But then comes the fierce opposition to his having any Department, threatening even to send charges into the Senate to procure his rejection by that body. Now, what I would most like, and what I think he should prefer too, under the circumstances, would be to retain his place in the Senate; and if that place has been promised to another, let that other take a respectable, and reasonably lucrative place abroad. Also let Gen. C’s friends be, with entire fairness, cared for in Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.”10

In mid-January 1861, Hiram Barney, George Opdyke and Judge John Hogeboom journeyed to Springfield on behalf of the Bryant faction of the party. Historian Donnal V. Smith wrote: “The Committee of Ten from New York stopped at Columbus on January 10, en route to Springfield, to discuss matters fully and freely with Governor Chase and to hear, no doubt, all that had been said during Chase’s conference with Lincoln. Arrived in Springfield, the committee was cordially received by the President-elect [on January 16] but politely informed that no further appointments would be made until he reached Washington, Lincoln indicated, however, that if the Pennsylvanians could be placated, he expected to name Chase as Secretary of the Treasury. Failing in their efforts to persuade the President to make the appointment at once, the committee returned to New York. After hearing the report of the committee, Bryant, Opdyke and others wrote to Lincoln, urging him to appoint Chase at once. They feared that unless Chase got into the Cabinet soon, Weed, acting through Seward, would gain control of the administration.11 Gideon Welles later recalled:

Mr. David Davis, since one of the justices of the Supreme Court but then a private citizen of Illinois and a confidential friend of Mr. Lincoln, and Mr. Leonard Swett, another intimate friend of Mr. Lincoln’s were more free in their communications, promises and concessions to Weed, and also to others who sought to forestall action, than Mr. Lincoln thought it advisable for him to be under the existing circumstances. The comments of the self-appointed ambassador on individuals and their relation to the Albany policy were listened to kindly, but without any satisfactory final, answering response. No committals for, or against any one were obtained from Mr. Lincoln and Weed returned in not a very complacent state of mind to Albany.

Though not satisfied, he could not make public his discontent. There was but one course for him to pursue in the great political contest of that year yet with a purpose in view there was some apparent holding off by the Albany clique, and also by certain Pennsylvanians, same three gentlemen (Weed, Davis and Swett) who have been named. Two others from Pennsylvania were also in the Saratoga conference, at which it was arranged that Mr. Seward should, in the event of the election of Mr. Lincoln, of which there was little doubt, receive as was generally expected the appointment of secretary of state, and Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania that of secretary of the treasury, which was not expected nor wished. This arrangement, though for the time apparently acquiesced in or not emphatically repelled was never ratified and carried into effect by President Lincoln.

The opposition of the Albany politicians to Mr. Chase caused Mr. Lincoln considerable embarrassment. They were particularly solicitous to exclude Mr. Chase from charge of the finances, being well satisfied that he would not relinquish his seat in the Senate to which he had just been elected for any place in the administration except he had just been elected for any place in the administration except that of the state or treasury. If, therefore, Mr. Seward could secure the state department and Mr. Chase be excluded from the treasury, the former would be relieved from a formidable rival, and have, it was believed, little difficulty in shaping the policy of the administration. The Saratoga conference worked to that end. Mr. Cameron had not readily and zealously espoused the support of the Republicans ticket, but stood measurably aloof after the nominations at Chicago. He was not a man who commanded general confidence even in his own State, and yet he had the tact and skill to control in a great degree the party politics and elections in Pennsylvania. His interest, his influence and his authority in all political matters were, then and always maneuvered by personal and selfish considerations. He probably knew not what it was to be disinterested on any subject, and had no conception of devotion or adherence to political principles of any kind or to party except for his own benefit.12

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles knew about the New York maneuvering from his own personal experiences: He wrote:

The few prominent men whom Mr. Lincoln consulted and letters from others whose opinions he esteemed more highly than those of the obtrusive and importunate gentleman from New York, strengthened him in his original purpose. On his way to Washington, and after his arrival at the seat of government, he ascertained from prominent and candid gentlemen whom he consulted in confidence that the line of policy which he had marked out, and the selections he had made, were more in accord with the wishes of his true friends than the narrow and restricted personal and party views of the Albany politicians. In point of fact, the sentiment of the Republicans in Washington he found less favorable to the selection of Mr. Seward than to any one whom he proposed to place in his cabinet.

Learning at an early day after the election that the President had my name under consideration, I forebore all communication with him, and declined, though earnestly advised and invited, to visit him or the seat of government while the subject of the formation of the cabinet was undetermined. Soon after the arrival of the President in Washington, I received a letter from James Dixon, one of the senators from Connecticut and a resident of my own town, written by request of Mr. Lincoln, propounding certain questions to me with reference to my appointment and a few days later a letter form the Vice-President-elect, Hannibal Hamlin, informed me that the President requested me to come to Washington. This summons I promptly obeyed.

Many of the facts related I learned at a subsequent period, the most important of them from Mr. Lincoln himself. The opposition to me by the Albany clique was very persistent and was not abandoned until after my arrival in Washington. It was their representation that I was an extreme states rights partisan and so obstinate and strict a constructionist as to be impracticable in my views and theories, which caused the President to request Senator Dixon to write me. Senator Preston King, the colleague of Mr. Seward in the Senate from New York with whom for twenty years I had been intimate, was most earnest and emphatic in favor of my appointment and was sleepless and unremitting in thwarting and defeating the intrigues of Weed and others against me.13

The Cabinet controversy was postponed by Mr. Lincoln’s decision not to make any final decisions until he arrived in Washington. The struggle over appointments continued right up until Mr. Lincoln’s inauguration. “Both Weed and Greeley were active in the struggle which toward the end of February raged around the question of Chase’s appointment,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “Both went to Washington in connection with this matter. Greeley in the Tribune accused Weed of opposing Chase’s entrance into the cabinet ‘with incomparable virulence, declaring that if he was appointed, the Union would certainly destroyed. Friends of Seward informed Lincoln on March 2d, that Seward would not serve with Chase. Weed, if a later report may be believed came away enraged because he failed to get Lincoln to omit Chase’s name, declaring that ‘Mr. Chase had been placed in the cabinet to control the patronage and appointments in the city and State of New York, to prevent Governor Seward from controlling the appointments, and to deprive him [Weed] of all power and influence.”14

Welles wrote: “When I reached Washington on the first of March, I found all the gentlemen, who a few days later were associated with me in the cabinet, already there; but unadjusted arrangements and complications which annoyed the President still existed. Opposition to myself had ceased for the President, weary of the harassment and vexations of the Albany partisans, had signified that so much of his programme was finally determined upon. The principal, and almost sole remaining difficulty related to the treasury. The friends of Mr. Seward, and the gentleman himself, were unwilling that Mr. Chase should have charge of the finances and claimed that by a previous general understanding, Mr. Cameron was to receive that appointment. But the President, while he had not rejected the Saratoga arrangement and by his silence had apparently acquiesced in it, was never fully committed to it. He had so far yielded to the pressure as to write in December, at the time when Weed went to Springfield, a letter to Cameron, stating that he proposed to tender him either the treasury or the war department. To this extent and no further was he committed.”15

It wasn’t just Chase and Cameron and other Cabinet positions who consumed Mr. Lincoln’s time. Richard McCormick, who met Mr. Lincoln on his visit to New York for his Cooper Institute speech, visited Springfield in January 1861 “at the instance of various friends in New York, who wished a position in the cabinet for a prominent Kentuckian [probably Cassius M. Clay]….I remained there a week or more, and was at the Lincoln cottage daily; indeed, I must say in passing, that I felt more at home there than at the barren hotel, and was the more free in my visits from the kind consideration of Mrs. Lincoln, who joined her husband in the suggestion that hotel life was at best comfortless, and that while in Springfield I should escape it as much as possible by tarrying with them, at the same time regretting that their house was not large enough for the entertainment of all their friends….”16

According to McCormick, “Of the numerous informal and formal interviews had at Springfield, I remember all with the sincerest pleasure. I never found the man upon whom the great responsibilities of a nation — upon the verge of civil commotion — had been placed, impatient or ill-humoured. The roughest and most tedious visitors were made welcome and happy in his presence; the poor commanded as much of his time as the rich. His recognition of old friends and companions in rough life, whom many, elevated as he had been, would have found it convenient to forget, was especially hearty. His correspondence was already immense, and the town was alive with cabinet-makers and office-seekers, but he met all with a calm temper….”17

Meanwhile, the political sides in New York drew up in Albany at the beginning of February to test their strength in the election to replace William H. Seward in the Senate. Tribune editor Horace Greeley was out in Illinois talking to President-elect Lincoln but his candidacy was supported by his deputy, Charles A. Dana, and such anti-Weed Republicans as David Dudley Field. Weed’s candidate was attorney William Evarts, who had headed the New York State delegation to Chicago for Seward. Weed took the election very seriously and had mobilized an impressive organization on Evarts’ behalf, observed the New York Tribune:

Mr. Evarts was surrounded by a band of the most skilful and experienced, the most throughly drilled and compacted corps of political managers in the country. Mr. Weed, a host in himself, led the cohort, flanked and followed by Comptroller Haws, Moses H. Grinnell, Simeon Draper, Oakey Hall,…and other eminent gentlemen from New York City; a large moiety of the State officers at Albany…and a crowd of men of like distinction from the Center, North and West; while a cloud of Harbor-Masters, Loan Commissioners, Canal Collectors, Canal Appraisers and other officials…covered the field as light dragoons, skirmishers and zouaves. It is estimated that the whole number of men collected here from all parts of the State by the managers of Mr. Evarts for the purpose of influencing, dragooning, and controlling the members of the Legislature in his behalf during the past week has not been less than one thousand….Never were the halls and parlors of the hotels, or the lobbies of the Legislature, thronged with such a feverish and intense activity.18

Evarts held a narrow lead on the first ballot with 42 votes to 40 for Greeley. A third candidate, Albany Judge Ira Harris had 20 votes. But Evarts’ votes slowly eroded while Greeley’s votes increased until Greeley had 47 votes on the eighth ballot and Evarts had 39. As Weed’s grandson told the story:

One hundred and fifteen Republicans attended the caucus, which was held during the first week in February. Their vote was almost exactly divided between Mr. Evarts and Mr. Greeley. A few scattering ballots were cast for Ira Harris, then a Justice of the Supreme Court. While the voting was in progress Mr. Weed, Governor Morgan, and Mr. Evarts were seated in the Executive Chamber. Eight ballots were taken without material change. On the ninth Mr. Greeley gained give votes, next ballot Mr. Greeley would be elected, unless prevented by a coup d’etat. Mr. Weed conferred with the Governor and with Mr. Evarts, and it was hastily decided that it was better to bestow the nomination on Judge Harris, than suffer the success of Mr. Greeley. Messengers were instantly despatched for leading Republicans, and the next ballot resulted: for Harris, sixty; for Greeley, forty-nine; for Evarts, two, scattering, six. Thus Judge Harris was elected.

‘The motives which prompted opposition to Mr. Greeley,'” writes Mr. Weed, ‘were patriotic and loyal. Republican members of the legislature cherished friendly feelings for a favorite editor; but they disapproved of his secession sentiments, and were unwilling to trust him with a seat in the United States Senate.’ Many, however, who aided in the election of Judge Harris, afterwards regretted that Mr. Greeley was not afford this opportunity to prove his fitness or unfitness for the high positions to which he aspired.”19

Rather than allow his rival Greeley to win the nomination, Weed had thrown the Evarts votes to Harris, who won on the 10th ballot. According to historian Sidney David Brummer, “Both sides claimed the victory. For many who had supported Greeley, it was indeed such; for the Weed slate had been broken. ‘The one-man power at the State Capital is overthrown,’ wrote the Tribune correspondent. ‘It was a conflict which was to determine whether a dynasty was to stand…or be overthrown or annihilated. Fully appreciating the fact, not Richard at Bosworth Field, Charles at Naseby, nor Napoleon at Waterloo, made a more desperate fight for Empire than did the one-man power at Albany to retain the sceptre it has wielded for so many years….”20

Greeley’s defeat reopened Republican wounds, observed historian Allan Nevins: “Nothing was now too harsh for Greeley to say about the humiliating surrender of Seward to the compromise spirit. ‘Mr. Seward Renounces the Republican Party,’ ran one of the Tribune headlines. Bryant’s Evening Post was equally virulent, for neither man could reconcile himself to the prospect of four years of government by what Samuel Bowles called ‘the New Yorker with his Illinois attachment.”21

Footnotes

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 105.

- Charles H. Brown, William Cullen Bryant, p. 423.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William Cullen Bryant to Abraham Lincoln, January 3, 1861).

- Charles H. Brown, William Cullen Bryant, p. 423.

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 39-40 (from Godwin, a Biography of William Cullen Bryant, Volume II, p. 152).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 1164 (Letter from William Cullen Bryant to Abraham Lincoln, December 25, 1860).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 163 (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to William Cullen Bryant, December 28, 1860).

- Elwin L. Page, Cameron for Lincoln’s Cabinet, p. 17-18.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 360-361 (Thurlow Weed).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 171 (Letter to Lyman Trumbull, January 7, 1861).

- Donnal V. Smith, “Salmon P. Chase and the Election of 1860”, Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, July 1930, p. 535-536.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 356-357 (Thurlow Weed).

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 359-360 (Gideon Welles).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 130.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 360 (Thurlow Weed).

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 253 (Richard Cunning McCormick, New York Evening Post, May 3, 1865).

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, Intimate Memories of Lincoln, p. 253-254 (Richard Cunning McCormick, New York Evening Post, May 3, 1865).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 133 (New York Tribune, February 4, 1861).

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 324-325.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 135 (New York Tribune, February 4, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861, Volume II, p. 446.