New York Tribune

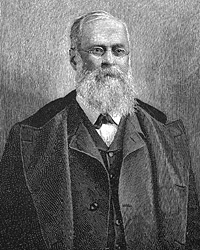

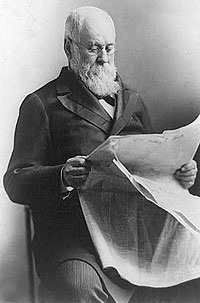

“Personally Mr. Dana was one of the most attractive and charming of men,” recalled New York politician Chauncey M. Depew. “As assistant secretary of war during Lincoln’s administration he came in intimate contact with all the public men of that period, and as a journalist his study was invaded and he received most graciously men and women famous in department of intellectual activity. His reminiscences were wonderful and his characterizations remarkable.”1 Charles A. Dana was appointed managing editor of the Tribune by Horace Greeley in 1849 after Dana returned from an extended trip to Europe. Dana probably met Greeley at Brook Farm, an experiment in Christian socialism where Dana was resident in the early 1840s and where Greeley was a frequent visitor.

Dana was “the most valuable of Greeley’s assistants,” wrote Greeley biographer Jeter Allen Isely. “He was a man of broad, general intelligence, a hard worker, a good administration and an formed and charming conversationalist.” Isely wrote: “Immediately upon joining the Tribune, Dana went abroad to cover the 1848 revolutions in Europe, where he came under the influence of the socialist Pierre Joseph Proudhon, and where he met Karl Marx, whom he subsequently engaged as a London correspondent for the Tribune. Dana returned to New York City in 1849, and until the Civil War was regarded as the ‘rising hope of the stern and unbending’ Radicals.’ His style was concise and firm. He was well versed in several languages, and enjoyed expounding foreign economic, political and military complexities.”2

The Dana-Greeley match was a difficult marriage that lasted for 13 years. Greeley was the public face of the Tribune — in his columns and his frequent lectures tours. Dana was the workhorse who managed the editorial product. “Like Greeley, Dana was ambitious, stubborn, vain and an opportunist. Though Dana understood from the start that he could advance his career by an association with the Tribune, the benefits of the arrangement were far from one-sided. Horace Greeley, aware of his own limitations as a manager, recognized the need for a lieutenant able to direct the daily operations of the paper. In Dana he believed he had found his man,” wrote journalism historian Janet Steele.3 Ultimately, Greeley found that the Tribune was big enough for only one vain man.

Dana biographer Charles J. Rosebault wrote: “There never could have been real sympathy between these two, even though they were in agreement on many of the great problems of the day. Dana was no less anti-slavery than his chief, but he was equally firm against secession. But it was in the more personal matters that there was a subtle antagonism. The exquisite young man could not but be offended at the manners and dress of the slovenly elder. Then the one was to a degree, at least, the product of college education, and convinced that the old-fashioned classical education, with Greek and Latin as its foundation, was indispensable to the making of the cultivated man; while the other had acquired what knowledge he possessed entirely through his own efforts and, as is often the [case with] self-educated, was inclined to belittle the value of college training.”4

After Dana’s dismissal from the Tribune, the Lincoln Administration found use for his considerable talents as a military troubleshooter. “Having met Charles A. Dana first in the spring of 1863, during the Vicksburg campaign it was my good-fortune to serve with him in the field during three of the most memorable campaigns of the Civil War, and for a short period under him as a bureau officer of the War Department. Our duties threw us much together, and of all the men I ever met he was the most delightful companion. Overflowing with the knowledge of art, science, and literature, and widely acquainted as he was with the leading men and movements of the times, his conversation was a constant delight and a constant instruction. Blessed with a vigorous constitution and an insatiable desire for information, he never once, by day or night, or in the presence of danger, however great, declined to accompany me on an expedition or an adventure,” wrote James Harrison Wilson, who was Dana’s friend and biographer.5

By that time in his life, according to military historian Harry J. Maihaifer, “Dana had left the idealistic serenity of Brook Farm some 17 years earlier, and nearly everything since had turned him away from that youthful idealism. Both in Europe and at home, he had observed people of influence: heads of state, politicians, journalists, business leaders. He had seen corruption, greed, naked ambition, and double-dealing. He had, in short, become a confirmed cynic.”6

Fellow journalist Alexander K. McClure described Dana as one of “the few men who enjoyed Lincoln’s complete confidence.”7 Friend Wilson wrote: “As a journalist and as Assistant Secretary of War, Mr. Dana was one of the most influential men of his time. Weighed for the strength and variety of his faculties, and for his power to interest and impress men’s minds, he must be considered as the first of American editors. Yet it happened that in the great era of the Civil War his energies were so powerfully called upon, and his services were so vigorous and effective, that he must also be classed among the real heroes of that unequalled conflict. By his pen no less that by his official action, he exerted a tremendous influence upon both the men and measures of his day. As field correspondent, and office assistant to Stanton, the great War Secretary, he was potent in deciding the fate of leading generals as well as in shaping the military policies of the Administration.”8

Wilson’s friendship may understandably have prejudiced Wilson to overrate Dana in comparison with his erstwhile boss, New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley. “Without attempting an elaborate analysis and comparison of the characteristics of these notable men, enough has already been quoted was the more virile and vigorous of the two. He was bolder, more aggressive, and more uncompromising in his conduct and opinions. His nerves were steadier, his muscles harder, his vision clearer, and his capacity for work greater. There is reason to believe that Dana stood with Greeley in resenting the treatment of the latter by [William H.] Seward and [Thurlow] Weed.”9

Dana was frequently more aggressive than Greeley — leading to irritation by the founding editor with his subordinate’s actions. “Dana had become dominant in the Tribune office and made much trouble for his superior, altering and suppressing his articles in accordance with his own journalistic judgment, which was generally good,” wrote Greeley biographer Don C. Seitz.10 “Dana indeed took liberties with Greeley’s orders, once printing details of a sensational divorce case rather than two congressional speeches that Greeley considered vital,” wrote Dana biographer Janet E. Steele.11

Dana was the stay-at-home managing editor and did not meet Mr. Lincoln before his election as President. But he put the Tribune solidly behind Mr. Lincoln’s campaign. The outbreak of the secession and the Civil War gave a forum for Dana’s aggressive inclinations — while Greeley himself exercised his neurotic instincts. According to Greeley biographer Jeter Allen Isely, “Dana assured Greeley that the southerners were in no position to fight, and that even if war came the battle would be neither long nor bloody. The managing editor stood in the vanguard of those members of the staff who believed that slavery had weakened the south the point of exhaustion.”12 James M. Perry wrote that Dana “and Greeley disagreed on a number of points in the days leading up to Bull Run. Dana later said — a little too simplistically — he was fired in April of 1862 because Greeley was for peace ‘and I was for war.'”13 On June 26, 1861, Dana was responsible for one of the most powerful headlines in the campaign:

FORWARD TO RICHMOND! FORWARD TO RICHMOND

The Rebel Congress Must Not be

Allowed to Meet There on the 20th of July

BY THAT DATE THE PLACE MUST BE HELD

BY THE NATIONAL ARMY14

Oliver Carlson, biographer of the Herald‘s James Gordon Bennett, wrote: “The news value of the Tribune during the spring and early summer of 1861 was very slight. Its whole tone and tenor were hysterical. It shrieked, it threatened, it scolded, and it denounced. Its columns were filled with rumors and counter-rumors; and with advice, mostly useless, to the government, to merchants, the public, to labor, and the farmers. It bragged and it boasted. It sniveled and sneered. It demanded action! — Action! — ACTION! And, as Benjamin Butler and others close the Washington scene later confessed — this demand for action by the Federal forces as expressed by the Tribune in its new slogan ‘On to Richmond,’ exerted great pressure on the Administration, paving the way for the disaster at Bull Run.”15

The “Forward to Richmond” campaign did indeed help push Union troops into the Battle of Bull Run and the resulting defeat pushed Greeley to the brink of a nervous breakdown. Conflict between the two men ebbed and flowed over the next eight months — until Dana was ousted on March 27, 1862. “Dana was shocked and angry at what he referred to as his ‘expulsion from the Tribune. In the words of newly appointed a managing editor Sydney Gay, ‘[Dana] avoids us all, is very dark, wounded, and is very bitter in his complaints.’ Dana believed he had been betrayed by his friends and that the real cause was Greeley’s vanity,” wrote Janet Steele.16 But the split was very surprising given their different temperaments and views about the war. As Dana himself later remembered the separation:

I have been associated with Horace Greeley on the New York Tribune for about fifteen years when, one morning early in April, 1862, Mr. Sinclair, the advertising manager of the paper, came to me, saying that Mr. Greeley would be glad to have me resign. I asked one of my associates to find from Mr. Greeley if that was really his wish. In a few hours he came to me saying that I had better go. I stayed the day out in order make up the paper and give them an opportunity to find a successor, but I never went into the office after that. I think I then owned a fifth of the paper — twenty shares; this stock my colleagues bought.

Mr. Greeley never gave a reason for dismissing me, nor did I ever ask for one, I know, though, that the real explanation was that while he was for peace I was for war, and that as long as I stayed on the Tribune there was a spirit there which was not his spirit — that he did not like.

My retirement from the Tribune was talked of in the newspapers for a day or two, and brought me a letter form the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, saying he would like to employ me in the War Department. I had already met Mr. Lincoln, and had carried on a brief correspondence with Mr. Stanton. 17

After Dana left the Tribune, he was succeeded by Sydney Gay, who y assumed an even more influential role in running the Tribune than Dana had played. Dana himself went from the frying pan directly into the fire. “Since Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861, Dana had worked at establishing close ties with key members of the president’s cabinet. Perhaps he suspected that a break with Greeley was inevitable and was hedging his bets in the event that he might soon be looking for another job,” wrote Steele. Dana became the eyes and ears of the President and the Secretary of War on the western war front. His first job was to “examine and report upon all unsettled claims against the War Department at Cairo, Illinois.” He left for Western front and arrived in Memphis in early July, 1862 and served for several months.

Dana’s services were such that in the fall of 1862, Stanton decided to make Dana one of his Assistant Secretaries of War. According to military historian Harry J. Maihaifer, Dana met with Stanton in mid-November and they agreed on the appointment: “Moments later, as Dana left the War Department, he ran into a fellow New Yorker, Maj. Charles Halpine, and mentioned his new job as Stanton’s assistant. Halpine immediately repeated the story to some newspaper people; the next morning it was reported in all the New York newspapers. Stanton took offense and rescinded the appointment.18

Dana then sought to go into the cotton-trading business with George W. Chadwick and New York Congressman Roscoe Conkling, who had been defeated for reelection that fall. But when Dana arrived in Memphis to conduct his business, Dana instead recommended to General Grant that he shut down this cotton trade completely — effectively destroying Dana’s own business interests. It was at this point that Grant issued his infamous order to “Refuse all permits to come south of Jackson for the present. The Isrealites especially should be kept out…” According to Grant biographer William S. McFeely: “Grant was fed up with the cotton speculators and the greedy suppliers of goods to his armies, but rather than attack the entire voracious horde, which included an astonishing assortment of entrepreneurs — among them Charles A. Dana and Roscoe Conkling, for example — Grant singled out the Jews.”19 One of President Lincoln’s White House aides, William O. Stoddard, wrote a sympathetic newspaper dispatch: “The host of cotton speculators, allured by the seeming promise of opening trade, will return home with empty pockets, and really they are to be pitied, for they have acted in good faith, relying on Government representations.”20

Dana returned to the western front in the early spring of 1863 with the job of investigating pay service for the War Department. According to Grant biographer Brooks Simpson: “In March, the administration decided on a course of action. Lacking reliable and disinterested sources of information about Grant and his command, Lincoln and Stanton decided that if they could not see things for themselves, they could choose someone to serve as their eyes and ears. Charles A. Dana, a former newspaper editor who was now a troubleshooter for the War Department, seemed ideal for the task….Grant had already complained that his men were not being paid on time, so the general might not suspect the true import of Dana’s mission. Receiving his orders on March 12 [1863], Dana immediately headed to Memphis.”21 The orders made Dana happy, according to biographer Steele: “Energetic, athletic, and a fine horseman, he yearned to be in the thick of the war. While his poor eyesight had ruled out the possibility of active military duty, his new job put him in the heart of the war effort.”22

Dana was quickly recognized for what he was — a spy. But Grant wisely insisted that Dana be treated hospitably and he indeed became one of Grant’s biggest boosters. Steele asked: “What turned Dana, ostensibly the agent of the secretary of war, into an unbridled champion of Ulysses S. Grant? As was typically the case with Dana, the motive was opportunism mixed with genuine admiration. Dana was obviously impressed with the general’s quiet confidence. Beyond that, he was energized by the excitement of war, the company of other men, and the break with domesticity. It is impossible to read either Dana’s cables to Stanton or his personal correspondence without becoming convinced of Dana’s sincerity.”23

In the spring of 1864, Dana once more was detailed by the President to check up on the progress of General Grant — this time with the Army of the Potomac. Mr. Lincoln told him: “Dana, you know we have been in the dark for two days since Grant moved. We are very much troubled, and have concluded to send you down there. How soon can you start.” Dana said he could be he would be ready in twenty minutes to take a train with a cavalry escort to find Grant. But when Dana boarded the train, he was recalled to the White House where the President said: “I have been thinking about this, Dana, and I don’t like to to send you down there.” The reason was the President’s fears for Dana’s safety. Dana replied: “Mr President, I have a cavalry guard ready and a good horse myself. If we are attacked, we are probably strong enough to fight. If we are not strong enough to fight, and it comes to the worst, we are equipped to run. It’s getting late, and I want to get down to the Rappahannock by daylight. I think I’ll start.”24

Dana performed signal functions for Stanton and Mr. Lincoln in addition to filing his detailed reports. He damned the character and career of General John A. McClernand and praised and protected the career of General Ulysses S. Grant. Indeed, with Congressman Elihu Washburne, Dana became one of the two foremost “experts” on the elusive Civil War commander. Such expertise was necessary because Grant did not even visit Washington until March 1864. Dana wrote Washburne: “My impressions concerning Grant do not differ from yours. I tell everybody that he is the most modest, the most disinterested, and the most honest man I have ever known. I have met hundreds of prominent and influential men to whom I have said that and other things in the same directions. To the question they all ask, ‘Doesn’t he drink?’ I have been able from my own knowledge, to give a decided negative.”25 Dana, however, was less than impressed by General George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac.

It wasn’t until 1864 that Dana finally got his promotion to Assistant Secretary of War — where President Lincoln occasionally used him to implement orders when the recalcitrant Stanton was out of the office. One task to which Dana was delegated was the collection of all Confederate records in Richmond. He left Washington on April 3, 1865 — accompanied by friend Roscoe Conkling, who had recently been reelected to Congress. Dana arrived in Richmond a day after President Lincoln had toured the city and began the collection of Confederate records. James Harrison Wilson wrote: “During his stay at Richmond Dana saw much of the President, and was in constant conference with him in reference to the conditions which they found prevailing about them, the questions which were coming up for solution, and the measures of government which it might be advisable to adopt. With both Lincoln and Andrew Johnson the Vice-President, on the ground to see for themselves, and with Grant in hot pursuit of Lee some sixty or seventy miles to the southwest, there was but little of important that the Assistant Secretary could send to the Secretary of War at Washington; but he was, as usual, alert and industrious. He sent a number of despatches which will be found in the Official Records. It was always a source of regret to him, however, that his attendance on the president had made it impracticable for him to join Grant in time to be present at the surrender.”26

Although he returned to journalism after the war, Dana did not lose interest in political appointments. According to biographer Janet Steele, three decades after President Lincoln’s death, Dana gave a speech in which he “seemed to suggest that he had been promised the [New York City Treasury] collectorship by Lincoln and that [Andrew] Johnson had reneged. Dana broached the issue by devoting a disproportionate amount of time to a seemingly obscure incident. He described in detail how, to obtain the House votes necessary to pass the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, Lincoln had authorized Dana to promise one New Jersey Democrat and two from New York whatever was necessary to obtain their support. Dana recalled:

I sent for the men and saw them one by one. I found that they were afraid of their party….Two of them wanted internal revenue collectors appointed. ‘You shall have it,’ I said. Another one wanted a very important appointment about the Custom House of New York. I knew the man well whom he wanted to have appointed. He was a Republican, though the Congressman was a Democrat. I had served with him in the Republican Party County Committee of New York.

According to biographer Steele, “The unnamed Republican whom the Democratic Congressman wanted appointed seems to have been Dana himself.”27 Dana never got his desired appointment — although he tried to get the post under both President Johnson and Grant. Dana served briefly and unsuccessfully as editor of the Chicago Republican. More successfully, in 1867, he became publisher and editor of New York Sun. In that position, Dana exercised a strong influence on broadening the thrust of post-war journalism.

Footnotes

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 344-345.

- Jeter Allen Isely, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 6-7.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 30.

- Charles J. Rosebault, When Dana Was the Sun: A Story of Personal Journalism, p. 50.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. xi.

- Harry J. Maihaifer, The General and the Journalists: Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Charles Dana, p. 144-145.

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 463.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. xi-xii.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 161.

- Don C. Seitz, Horace Greeley: Founder of the New York Tribune, p. 207-208.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 41.

- Jeter Allen Isely, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 324.

- James M. Perry, The Bohemian Brigade, p. 48.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 334.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 324.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 45.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 25.

- Harry J. Maihaifer, The General and the Journalists: Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley, and Charles Dana, p. 134.

- William S. McFeeley, Grant: A Biography, p. 123.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 146 (April 6, 1863).

- Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822-1865, p. 179.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 53.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 53.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 114-115.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 55 (Letter from Charles A. Dana to Elihu Washburne, August 29, 1863).

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 357.

- Janet E. Steele, The Sun Shines for All: Journalism and Ideology in the Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 72.