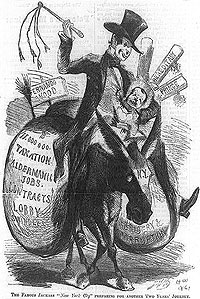

New York City politics was not for the faint of heart. “Our city legislators, with but few exceptions, are an unprincipled, illiterate, scheming set of cormorants, foisted upon the community through the machinery of primary elections, bribed election inspectors, ballot box stuffing, and numerous other illegal means,” editorialized the New York Herald in January 1860. “The consequence is that we have a class of municipal legislators forced upon us who have been educated in barroooms, brothers and political societies; and whose only aim in attaining power is to consummate schemes for their own aggrandizement and pecuniary gain.”1

The powerful Tammany Hall organization had broken apart in the 1850s over conflicts which originated in the corrupt government of Mayor Fernando Wood. Ironically, some of the problems developed in his first term in office which was relatively progressive and honest. Wood ordered enforcement of laws requiring that saloons be closed on Sunday and a crackdown on prostitution. According New York City historian Oliver E. Allen, Tammany Hall regulars never forgave “him for striking out against the saloons, and they were also irked because he had gone back on a number of promises made to party regulars for city offices — Tammany did not break its word. He was allowed to run again but received only lackluster support and went down to defeat [in 1857]. Indignant, he led his supporters out of Tammany and formed a rival known a Mozart Hall (for the building where it met). In 1859, with Tammany unable to come up with a strong candidate, Wood somehow made it back into City Hall under the Mozart aegis.”2

The split worsened during the 1860 Democratic presidential and state conventions when Mozart Hall challenged Tammany delegations for their convention seats — and adopted positions much more sympathetic to Southern Democrats and secessionists. Historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace wrote that Democratic divisions “cost their party the mayoralty in 1861, when Tammany’s C. Godfrey Gunther and Mozart’s Wood divided the Democratic vote, allowing Republican George Opdyke — a wealthy dry-goods importer, banker, and broker and a leader in the Union Defense Committee — to capture City Hall with barely more than one-third of the vote.”3 Opdyke was a Radical Republican whose anti-slavery views came under attack in the campaign.

Republicans blundered in October, according to historian Jerome Mushkat, when the Fifth Avenue Committee, the St. Nicholas Committee, the German League, and the Tax-Payers Committee [were] linked with the Republicans on a Unionist, reformist slate.”4 Their unity spurred Democratic unity as well. But the many reform groups were also symptomatic of their disunity. “Insurgents divided between such groups as Taxpayers Party, St. Nicholas Hotel, Fifth Avenue Hotel, German League, Cooper Institute Reform, and People’s Union. What each group generally stood for was self-aggrandizement, reform and lowering of the tax rate. The electioneering was typical of all New York politics — a fragmented nightmare,” wrote Leo Hershkowitz in Tweed’s New York: Another Look 5 Eventually, the Rent-Payers Association joined the others in supporting George Opdyke’s candidacy.

Meanwhile, wrote Tweed biographer Alexander B. Callow, Jr., Fernando “Wood slyly came forward with a compromise proposal couched in persuasive terms of party harmony. Mozart would call off the war with Tammany, if Tammany in turn would give its backing to Wood for Mayor. It was an adroit tactic. Tweed’s acceptance would have actually signalled his surrender, for if Wood regained the mayor’s office, he would be in a formidable position to destroy Tweed politically. While Tweed refused, he did make a sensible compromise regarding candidates for the State legislature and some unimportant city offices. He agreed that both Tammany and Mozart would share in offering candidates for these offices. Compromise on this level was realistic and necessary, because Wood’s Mozart Hall was powerful enough in 1861 to challenge Tammany.”6 Historian Mushkat wrote: “Both Halls cooperated, but only on an informal level, and selected independent slates although they substantially agreed on a number of common nominees. As to three vital offices, however, those of mayor, district attorney, and sheriff — confusion reigned.”7

Biographer Callow wrote: “The crux of the fight, however, lay in who would win the city— and county-wide offices. Here Tweed prepared for an all-out battle. He was ‘determined that Wood should be destroyed, even if it meant the sacrifice of every man on the regular Democratic city and county tickets….'” Callow noted that although Tweed lost his own campaign for sheriff, “it was a resounding victory for William Marcy Tweed, because the ultimate goal was achieved. Fernando Wood was beaten at the polls.”8

Gunther was a wealthy New York fur merchant whom Tammany hoped would attract German-American voters. But even if he did not win, Tammany Hall hoped he would defeat Mozart Hall and Wood, who had revived his Southern sympathies after a short-lived bout of Union patriotism in the spring of 1861. “Significantly, the attitude of the candidates toward the war was the chief issue of the campaign,” wrote Sidney David Brummer. “Wood declared that the contest was one of conservative nationalism against abolitionism; and claiming that he was the representative of the former, he devoted his speeches largely to denunciation of the latter. At a mass meeting of Germans, he was reported to have said:

They [the abolitionists] will prosecute it [the war] so long as there is a drop of Southern blood to be shed, provided they are removed from the scene of danger. They will get Irish and Germans to fill their regiments to ‘defend the country’ under the idea that they themselves will remain at home, and divide the plunder…They have conquered all the strongholds of the North, and they are now battling against the citadel of the Empire City…9

“When the South fired on Fort Sumter, Wood proved capable of reversing himself. He ordered Mozart Hall to organize a volunteer regiment and waved the flag of patriotism as fervently as anyone else did. But he never really seemed to favor active prosecution of the war, and the conflict marked the end of his career as Manhattan’s leading political figure. His ambivalence toward the Union tinged Mozart Hall with treason,” wrote CHECK in The Age of the Bosses.”10 The New York Herald reported: “The two principal features of the canvass were the anti-Wood cry and anti-abolition.”11 Historian Mushkat wrote that Wood had wanted to campaign on local issues, but because “Opdyke’s supporters had preempted reform, Wood abandoned his plans to conduct a vigorous, high-level, locally orientated campaign, and made Lincoln’s handling of the war the chief election issue. The mayor’s move was a major switch in tactics, for as late as November 2 he had pledged the Administration his support. But now that he was fighting for his political survival, Wood could no longer live in two worlds.”12

William Alan Bales wrote that Wood had his political back up against the wall: “Once, he said he could have committed a murder in his family and won election. But now he had stolen city money and even worse, the story was out.”13 Historian Brummer wrote: “In general, the supporters of Opdyke and of Gunther attacked the candidates of each other by sparingly, and turned their fire rather against the crafty Mozart chief. Whether to vote for Opdyke or for Gunther, was with many simply a question of which had the better chance of defeating Wood. Neither of the Democratic factions could afford to be beaten by the other. It was the closest triangular contest thus far fought in the City; the vote was very heavy, from fifteen to twenty thousand above that cast in the state election a month previous, and after making allowance for the number absent in the army, rivaling the presidential vote of 1860.”14

Wood made a critical mistake when he condemned the Lincoln Administration’s military and anti-slavery policies in a speech before the German Americans at the Volks Garten. “For once Wood’s political cynicism skewered him,” wrote historian Mushkat. “Totally oblivious to the emotions involved, he could not understand that the public took the war seriously and demanded consistency. Where New Yorkers could once forgive his drive for personal advancement, they could no longer accept his methods. Quite simply, they felt that saving the Union was far too worthy a cause for such cheap gamesmanship.”15

The election was tough, rough and close. Attorney George Templeton Strong wrote the day after the election: “Opdyke is mayor, Wood having failed of reelection by a chose shave. I have no sort of faith in Opdyke, but he is certainly not proven to be quite as bad as his predecessor.”16 The vote was very close. Opdyke received 25,380 votes while Gunther came second with 24,767 and Mayor Wood ran last with 24,167 votes.

In part because of past corruption, New York mayors had little power. The State Legislature had limited the damage could do over two years. Furthermore, the mayor’s “power over the city patronage,” wrote Sidney David Brummer, “was checked by a hostile common council which again and again rejected his nominations: the heads of the street cleaning and city inspector’s departments, under which lay the bulk of the municipal spoils, had yet a year of office, and they, as well as other heads of departments except the controller and the corporation counsel, both of whom were elected, were irremovable except with the consent of the board of alderman and for cause; the police were wholly without the mayor’s power and were governed by a metropolitan police board; finally the board of supervisors, a bi-partisan body, exercised legislative and executive functions over county matters.”17

Having won the mayor’s office, the Republicans exhibited Democrat-like jealousy between their Thurlow Weed wing and anti-Weed wing. The battle took place in the State Assembly, where Henry J. Raymond, editor of the New York Times and Weed ally, was speaker. After Wood was defeated in 1861, Mayor Opdyke sought to restore some of the office’s powers. “In order to hit Fernando Wood, the mayor of the metropolis had been reduced almost to a figurehead,” noted historian Brummer. “But many thought there was no longer any reason for this, now that Wood was out of office. Despite the fact that Raymond had been supported by Opdyke in the speakership contest, the former, it was said, had arranged the committee on cities so that all the Republicans on it belonged to the Weed wing. Opdyke went up to Albany to oppose the metropolitan health bill. Thereupon, the Times, Raymond’s paper, came out with the remark, ‘The public will hear with amazement that Mr. Opdyke has been at Albany opposing this bill.’ The Tribune took up the cudgels in Opdyke’s behalf. The Times then turned its guns upon the Tribune. ‘The Tribune,’ it said, ‘betrays its own motive…Its determination is to defeat this bill unless it can secure for the Mayor and his immediate friends, the political power which it attributes to the bill. We regard this…as sacrificing every consideration of the public good to the base malignity of a faction.’ In the end Opdyke, the Tribune, and their adherents succeeded in partially accomplishing their purpose, for the Senate so changed the control of the patronage involved in the bill, that the original supporters of the measure dropped it. But on the other hand, no amendment to the charter of New York City was passed and Opdyke obtained no increase of power.”18

By 1863, a new faction had entered the ranks of New York City Democrats — one lead by John Keon. According to historian Mushkat, “After the [1863 Draft] riot, an odd collection of anti-Wood Peace Democrats, reform-minded businessmen, independent Irishmen, and disappointed office-seekers coalesced around John McKeon’s leadership. With this inter— and intra-party fusion, the McKeonites demanded that the state party give them sole local recognition at the coming convention.”19 He picked up the 1861 Tammany candidate for mayor, C. Godfrey Gunther. The McKeonites had been stymied at the Democratic State Convention in September when Tammany Hall and Mozart Hill combined to block their delegates from being seated. Meanwhile, Mozart Hall began to splinter — one group joined the new McKeon faction and one group stuck with Wood.

Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “Determined efforts were made to nominate General Dix for mayor, but he refused to allow his name to be used in that connection.”20 President Lincoln also refused to be drawn into the campaign. In early November 1863, Mr. Lincoln wrote to John J. Astor, Jr., Robert B. Rosevelt, and Nathaniel Sands, who sought his aid in recruiting General Dix: “Upon the subject of your letter I have to say that it is beyond my province to interfere with New York City politics; that I am very grateful to Gen. Dix for the zealous and able Military, and quasi civil support he has given the government during the war; and that if the people of New York should tender him the Mayoralty, and he accept it, nothing on that subject could be more satisfactory to me— In this I must not be understood as saying ought against any one, or as attempting the least degree of dictation in the matter. To state it in another way, if Gen. Dix’ present relation to the general government lays any restraint upon him in this matter, I wish to remove that restraint.”21

Dix wrote President Lincoln the next day: “Your letter in regard to the Mayoralty of this City reached me after I had declined the nomination. There were many insurmountable objections of a personal character to my acceptance; but I was also of the opinion that I could be more useful to Your administration where I am, and many of Your most discreet friends coincide with me. I did not understand Your letter as expressing any opinion or wish on the Subject, but merely as an intimation that, so far as depended on You, obstacles would be removed, should I deem an acceptance advisable. If I could have a few minutes’ conversation with You, I know You would be satisfied that my decision is right. I am only anxious to be where You think I can be most useful to the Country.”22

Brummer wrote: “The Unionists then selected Orison Blunt for their candidate. The McKeon Democracy, a reform movement hoping to cleanse the party of its corrupt influences, had already put forth C. Godfrey Gunther, a businessman and volunteer fire company activist who had been the Tammany nominee for the same office two years before. It was led by John McKeon, who had served in numerous political positions from Assembly to Congress, from District Attorney to U.S. Attorney Tammany and Mozart united on Francis I.A. Boole, a leading figure in the aldermanic ring.”23 Blunt was a Radical Republican and civic activist who served as chairman of the New York County Volunteer Committee that encouraged enrollment of troops from the city. The campaign was in contrast with others of this period in that national issues once more were subordinated to local matters. Although the McKeonites had been shut out from the last state convention and had polled only about four thousand votes in November, Gunther was elected by about 6,500 plurality. The result was interpreted as a repudiation of the Tammany and Mozart machines and as a vote against government by bargain and in favor of an honest judiciary.”24

“Tweed did not panic,” wrote Jerome Mushkat. “His major concern was to achieve a final consolidation of power by dominating the mayoralty, and he had sacrificed the state ticket in order to do so. In a way, prospects looked bright. The Republicans, after failing to coax General John Dix into the race, settled on a poor choice, Weedite Orson Blunt, a man Greeley had helped defeat for Congress two years before.”25 Tammany candidate Boole “had recently gained immense public approval by reforming some obnoxious slaughterhouse practices and making popular changes in the city’s methods of garbage collection. A War Democrat, Boole won the Herald‘s endorsement,” wrote Mushkat.26

The 1863 election exposed Tammany Hall’s continued woes” in poor areas like Five Points, wrote Tyler Anbinder. “The Irish-American explained Gunther’s victory by observing that ‘the people, who, for a long while, have not been content with the manner in which the political ‘machines’ have been run for the exclusive profit of a score or two of political dictators, voted for the only candidate who appeared to be running without any machinery at all, and elected him.”27 Although it was a defeat for the Democratic political bosses, it was not a victory for President Lincoln. Gunther was a Peace Democrat and no friend of the President or his policies. After his murder, Gunther’s reaction was distinctly cooler than was that of other New York politicians; he vetoed publication of the records of the Committee on Arrangements for Mr. Lincoln’s funeral.

Nevertheless, state and national conflicts were played out on the Republican side in the 1863 race. Historian John Niven wrote: “Chase continued to back Barney, even after he learned that the collector’s private secretary, Albert Palmer, his chief patronage dispenser and political organizer, was secretly acting for Weed and was directly responsible for the defeat of the radical ticket in the New York city mayoralty contest.”

Footnotes

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 237.

- Oliver E. Allen, New York, New York: A History of the World’s Most Exhilarating and Challenging City, p. 162.

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, p. 885.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 331.

- Leo Hershkowitz, Tweed’s New York: Another Look, p. 84.

- Alexander B. Callow, Jr., The Tweed Ring, p. 26-27.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 332.

- Alexander B. Callow, Jr., The Tweed Ring, p. 26-27.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 176.

- The Age of the Bosses, p. 100.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 177 (New York Herald, December 8, 1861).

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 333.

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 113.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 177.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 334.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 196 (December 14, 1861).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 32-33.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 190-191.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 353.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 354.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to John J. Astor Jr., Nathaniel Sands, and Robert B. Roosevelt, November 9, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. November 10, 1863.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 354.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 354.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 354.

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, p. 354.

- Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum, p. 318.