New York Senator Ira Harris was among President Lincoln’s “most frequent evening visitors,” wrote Lincoln biographer Benjamin Thomas.1 His frequent presence made him privy to the President’s patronage — so much so that the President once claimed that he looked underneath his bed each night to check if Senator Harris was there, seeking another patronage favor.2 David M. Jordan, biographer of the man who replaced Harris in the Senate in 1867, wrote that Harris “had served a nondescript, middling term through the most exciting period in American history.”3

Harris’s frequent presence at the White House gave him insight into President Lincoln’s past. Once, Senator Harris was present at the White House when President Lincoln admitted “It may seem somewhat strange to say, but I never read an entire novel in my life.” Harris asked: “Is it possible?” Replied the President, “Yes, it is a fact. I once commenced ‘Ivanhoe,’ but never finished it.”4 Harris’s visits also made him privy to President’s thinking. At the conclusion of the Cabinet crisis in December 1862. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase turned in his resignation — providing the necessary balance to [Secretary of State William H.] Seward’s earlier letter of withdrawal from the Cabinet. When Senator Ira Harris entered the office after the President received Chase’s letter, Mr. Lincoln told him: ‘Yes, Judge, I can ride now — I’ve got a pumpkin in each end of my bag.’5

Harris’s visits also made him a natural conduit of communication to the President. During the Peninsula campaign in the summer of 1863, General Erasmus D. Keyes wrote Harris that the Union “must have one line of operations and one army, under one general.” He added: “Please show this letter to the President.”6 Harris was one of the nine-member delegation of Senators that called on the President on December 18, 1862. According to Seward biographer John M. Taylor, “”The meeting then focused on Seward, who was roundly condemned by [Charles] Sumner, [James] Grimes and [Lyman] Trumbull. Sumner complained about Seward’s handling of foreign affairs, especially the letter to [U.S. Minister to France William] Dayton in which Seward had equated abolitionists with the rebels. Trumbull took Seward to task for his ‘little bell.’ Grimes insisted that he had ‘no confidence whatever’ in the secretary of state. But when Lincoln asked bluntly whether all present wanted Seward out of the cabinet, only [Samuel] Pomeroy of Kansas joined the trio of Sumner, Grimes and Trumbull. New York’s Ira Harris said that Seward’s influence in New York was such that his departure from the cabinet would injure the party, while the others were noncommittal.”7

Harris was close to Seward — to whose political machine Harris owed his election to the Senate. Prior to that, Harris had been a law professor and served for 13 years as a State Supreme Court judge at Albany. He had lectured at the Columbian College of Washington and served the American Baptist Missionary Union. In February 1861, he was selected as a compromise choice of Republicans to succeed Senator William Henry Seward. He wasn’t the first choice of New York Republicans — who were split at an Albany convention between attorney William M. Evarts, backed by New York Republican boss Thurlow Weed, and New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, backed by opponents of Weed. On the first ballot of the Republican caucus, Evarts and Greeley tied with 40 votes — twice the total which Harris polled.

According to Greeley biographer William Harlan Hale, “Weed, usually so amiable and serene as he moved through the lobbies with his stately gait and whitening hair, was worried this time. On the first ballots, Greeley was showing extraordinary strength. The boss retired to the Governor’s room and bit his cigar. Fearing that Evarts might not pull through Weed had given his blessings to a third entry in the race — the former antirenter, Judge Ira Harris — whom he kept in the background for possible emergency use.”8 Hale seems to overstate Weed’s role since Harris had been a candidate since the first ballot. “On the seventh caucus ballot, Greeley began pulling well ahead of Evarts, with the insignificant Harris trailing. Another ballot like this and Greeley might win against the whole machine. Hurriedly Weed issued his orders: all Evarts men were at once to switch their votes to Harris,” wrote historian Hale.9 Harris then defeated Greeley in the Caucus and went on to defeat Democrat Horatio Seymour in the full legislature.

“The eighth ballot showed a marked trend to Greeley,” wrote the authors of A History of New York State. “When the news reached Weed, he thrust a cigar in his mouth, completely unaware that he already had one between his lips, lighted it, and said excitedly to the messenger, ‘Tell the Evarts men to go right over to Harris — to Harris — to Harris!”10 When a Republican assemblyman rushed up to Weed during the proceedings to inquire if the boss knew candidate Harris, Weed replied: “Do I know him personally? I should rather think I do. I invented him.”11 For Greeley, who was in the West on a lecture tour during the caucus balloting, the loss was merely the latest battle in the long war between himself and the Seward-Weed machine.

Senator Harris was with Secretary of State William H. Seward on December 27, 1861 when he reviewed the resolution of the Trent Affair with England. “After an arduous day’s labor, Seward returned home early on the evening of December 27 to host a dinner for English novelist Anthony Trollope and several prominent United States senators. Afterward the secretary of state invited Senators Orville H. Browning, John J. Crittenden, Ira Harris, Preston King, and Charles Sumner to his library, where he read them the documents pertaining to the Trent affair which he was about to release to the newspapers. Included among those documents were the British ultimatum, his own reply thereto, Thouvenel’s dispatch on the subject, Seward’s reply to that, and, finally, the secretary’s conciliatory instruction regarding the seizure of Mason and Slidell which he had sent on November 30 to [Charles Francis] Adams at London. When Seward finished reading all these papers, the assembled senators apparently ‘all agreed with him’ that the captured Southern diplomats ‘should be given up.'”12

Harris was not one of the Senate’s great movers and shakers. He failed to win reelection after his first term. But he impressed William O. Stoddard, who claimed that Harris had promoted him for his job as a White House assistant. Stoddard returned the favor with at least four positive mentions in the newspaper column he wrote anonymously for the New York Examiner:

- June 6, 1861: “Senator Harris, of New-York, has been here for several days, and is looking in much better health than during the last session of Congress.”13

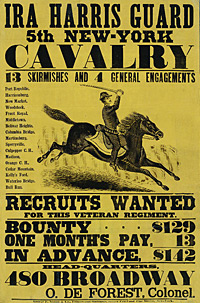

- December 8, 1861: “I wound up my day’s work by witnessing the presentation of a handsome flag to the ‘Harris Light Cavalry,’ by the distinguished Senator whose name the corps has adopted. The speech of Senator Harris was brief, dignified and earnest, worthy of him….”14

- February 3, 1862: “The expulsion of Senator Bright has hardly left a ripple of sensation. We are too busy with weightier matters to pause long over the disgrace of one man, right or wrong. The course of Senator Harris, of your State, has occasioned some remark. Few men would have ventured to take such a stand, even if sure that they were in the right; and no man can question the upright motives of the Senator from New York.’15

- March 31, 1862: “This afternoon, if nothing prevents, Senator Harris is to give his long-expected speech on the confiscation question, and the galleries will be crowded, for the course of the honorable Senator, thus far, has been such as to give an unusual weight to his counsel upon the great questions of the day.”16

Stoddard, a former Illinois editor, did not write of the controversy which Senator Harris created in February 1862 when he voted against the expulsion of Indiana’s John Bright from the Senate. In response, the New York State Legislature passed a resolution commending Bright’s expulsion and commending Senator Preston King for voting for it.

Although elected by the Seward-Weed machine, Harris did not always approve of it. Gideon Welles wrote in his diary during the 1864 campaign: “Senator Harris called on me. He is jubilant over [General Philip H.] Sheridan’s success, but much disturbed by the miserable intrigues of Weed and Seward in the city of New York. Says he has told the President frankly of his error, that he has only given a little vitality to Weed, whose influence has dwindled to nothing, and would have entirely perished but for the help which the President has given him. This he is aware has been effected through Seward, who is a part of Weed.”17

Not all of Harris’ interactions with the Lincoln family were happy. In late 1863, Mary Todd Lincoln’s widowed sister, Emilie Helm, was visiting the White House when Mrs. Lincoln requested that she meet some visitors. The Confederate Helm later wrote:

I went most reluctantly. It is painful to see friends and I do not feel like meeting strangers. I cannot bear their inquiring look at my deep crepe. It was General [Daniel] Sickles again, calling with Senator Harris. General Sickles said, “I told Senator Harris that you were at the White House, just from the South and could probably give him some news of his old friend General John C. Breckinridge.” I told Senator Harris that as I had not seen General Breckinridge for some time I could give him no news of the general’s health. He then asked me several pointed questions about the South and as politely as I could I gave him non-committal answers. Senator Harris said to me in a voice of triumph, “Well, we have whipped the rebels at Chattanooga and I hear, madam, that the scoundrels ran like scared rabbits.” “It was the example, senator Harris, that you set then at Bull Run and Manassas,” I answered with a choking throat. I was very nervous and I could see that Sister Mary was annoyed. She tactfully tried to change the subject, whereupon Senator Harris turned to her abruptly and with an unsmiling face asked sternly: “Why isn’t Robert in the Army? He is old enough to serve his country. He should have gone to the front some time ago.”

Sister Mary’s face turned white as death and I saw that she was making a desperate effort at self-control. She bit her lip, but answered quietly, ‘Robert is making his preparations now to enter the Army, Senator Harris; he is not a shirker as you seem to imply, for he had been anxious to go for a long time. If fault there be, it is mine. I have insisted that he should stay in college a little longer as I think an educated man can serve his country with more intelligent purpose than an ignoramus.” General [sic] Harris rose and said harshly and pointedly to Sister, “I have only one son and he is fighting for his country.” Turning to me and making a low bow, “and, Madam, if I had twenty sons they should all be fighting the rebels.” “And if I had twenty sons, General Harris,” I replied, “they should all be opposing yours.” I forgot where I was, I forgot that I was a guest of the President and Mrs. Lincoln at the White House. I was cold and trembling. I stumbled out of the room somehow, for I was blinded by tears and my heart was beating to suffocation. Before I reached the privacy of my room where unobserved I could give way to my grief, Sister Mary overtook me and put her arms around me. I felt somehow comforted to weep on her shoulder — her own tears were falling but she said no word of the occurrence and I understood that she was powerless to protect a guest at the White House from cruel rudeness.18

Despite the incident, Mrs. Lincoln remained on good terms with Senator Harris, writing a friend at the end of the congressional session in March 1865: “Judge Harris called last evening, to say, farewell. He has been so kind a friend that I am quite as attached to him as if he were a relative.”19

Harris’s son William was a colonel in the Army Ordnance Department. Harris’ daughter Clara and her fiancé Major Henry Rathbone, who was Harris’ stepson, were the Lincolns’ guests for the theater on the night of April 14, 1865. The Lincolns were late in picking up the couple at the Harris residence and late arriving at the theater. “The beautiful weather of the morning had given way to fog as the presidential carriage turned out of the White House gates,” wrote biographer Benjamin Thomas. “Gas jets on the street corners glimmered faintly through the mist. The sodden air muffled the horses’ hoofbeats. At half past eight Charles Forbes, the White House coachman, drew rein in front of Ford’s Theater.’20 The Lincolns were alone with their guests when John Wilkes Booth entered their box at the Ford Theater and assassinated the President. Clara Harris subsequently married Rathbone. Tragically, her husband later went insane and killed her.

Footnotes

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 476.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 264.

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 85.

- Francis Fisher Browne, The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 647.

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, .

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume I, p. 490.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward, p. 209.

- William Harlan Hale, Horace Greeley: Voice of the People, p. 238.

- William Harlan Hale, Horace Greeley: Voice of the People, p. 238.

- David M. Ellis, Jams A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 241.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 264.

- Ferris, The Trent Affair, p. 188.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 8 (June 6, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 47 (December 8, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 58 (February 3, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 72-73 (March 31, 1862).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 155 (September 21, 1864).

- Katherine Helm, The True Story of Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 228-230.

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 210 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Charles Sumner, March 23, 1865).

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 518.