“It is difficult now to recreate the scenes of that campaign. The people had been greatly disheartened,” wrote Republican politician Chauncey Depew who took an active role in rallying New York State Republican voters. “Every family was in bereavement, with a son lost and others still in the service. Taxes were onerous and economic and business conditions very bad. Then came this reaction, which seemed to promise an early victory for the Union. The orator naturally picked up the phrase, “The war is a failure”; then he pictured [Admiral David] Farragut tied to the shrouds of his flag ship; then he portrayed [Ulysses S.] Grant’s victories in the Mississippi campaign, [Joseph] Hooker’s “battle above the clouds,” the advance of the Army of Cumberland; then he enthusiastically described [General Philip] Sheridan leaving the War Department hearing of the battle in Shenandoah Valley, speeding on and rallying his defeated troops, reforming and leading them to victory, and finished with reciting some of the stirring war poems.”1

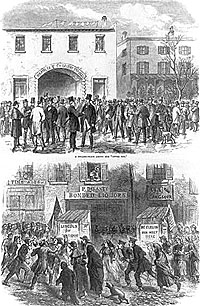

“The Presidential election of 1864 was another critical period in the history of the war, and full of threats against the peace and safety of New York City,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt. “There were serious expectations of both fraud and violence at the polls. General Dix, upon reliable information, warned the officials that agents of the Confederacy in Canada were plotting to colonize in the city, as in other places, large companies of refugees, deserters, and malcontents, who were to vote against Lincoln on election day; and prepared even to go to the extreme of subsequently ‘shooting down peaceable citizens and plundering private property’; a repetition of the work of 1863. Detectives were accordingly placed upon the watch. All arrivals in town were carefully scrutinized, and made to give an account of themselves.”2

General Dix issued orders on October 28, according to historian Sidney David Brummer “that he had received satisfactory information that reel agents in Canada designed to send into the United States large numbers of refugees, deserters and enemies of the government to vote at the approaching election, and that he was determined to guard the purity of the elective franchise against the threatened outrages; every such person was to be arrested, provost marshals were directed to exercise all possible vigilance, and all persons from the insurgent states were required forthwith to report themselves for registry. In a letter of October 29th, Senator [Edwin D.] Morgan wrote to Stanton both at the request of others and in accordance with his own judgment, desiring that three thousand troops be sent to New York immediately. Stanton had already urged on Grant the advisability of such a move.”3

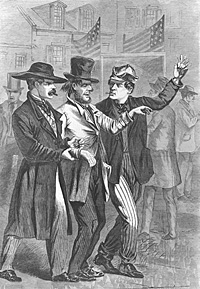

Dick Nolan, biographer of General Benjamin Butler wrote: “As military affairs settled down to routine, the Lincoln administration had one further chore for Butler to perform. There were rumors that Copperhead conspirators and rebel spies proposed to disrupt the election balloting in New York, so Butler was dispatched there with five thousand troops to keep the peace. This he did without difficulty or incident, aside from a number of assassination threats, which Butler ignored and which came to nothing. New York conducted the quietest election in its history so that even the most timid of Lincoln’s supporters found no excuse to stay away from the polls.”4 Butler wrote in his memoirs that he received a set of orders containing a report on the situation in New York City:

I carefully read the papers. They were the reports of his confidential agents and detectives, and of prominent loyal men in the city and State as to the condition of affairs there. They contained matter sufficiently alarming, but, as is always the case, exaggerated.In substance they stated that there was an organization of troops which was to be placed under command of Fitz John Porter; that there was to be inaugurated in New York a far more widely extended and far better organized riot than the draft riot in July, 1863; that the whole vote of the city of New York was to be deposited for [George B.] McClellan at the election to be held just one week from that date; that the Republicans were several thousand rebels in New York who were to aid in the movement; and that Brig.-Gen. John A. Green, who was known to be the confidential friend of the governor, was to be present, bringing some forces from the interior of the State to take part in the movement.The fact of such an organization was testified to over and over again. The number of troops on Governor’s Island under General [John A.] Dix, who commanded the Department of the East, was shown to be very small, indeed, and was counted on as unreliable, as they were a garrison of the regular army.5

Butler biographer Dick Nolan wrote: “There were rumors that Copperhead conspirators and rebel spies proposed to disrupt the election balloting in New York, so Butler was dispatched there with five thousand troops to keep the peace.’6 Butler wrote that Stanton ordered him to New York relieve General John A. Dix, a venerable New York politician, but that Butler suggested he instead be subordinate to Dix. “But,” protested Stanton, “Dix won’t do anything. Although brave enough, he is a very timid man about such matters, as he wants to be governor of New York himself one of these days.”7 Butler left Washington for New York, where he arranged to occupy a hotel as his headquarters. Butler wrote:

Early in the morning of the 4th of November I occupied my headquarters. As the first incident I learned that one Judge Henry Clay Dean, in utter ignorance that I was at that time in New York, had made a speech the night before in which, according to a newspaper report, he stated that if I should attempt to march up Broadway I would be hanged to a lamp-post, or words to that effect. Although I had no troops in New York then except my orderlies and aids, I sent my compliments to Judge Dean with the information that I would like to see him at my headquarters at the Hoffman House. He reported at once, and I received him. He seemed to be in a great fright. I greeted him and told him that such a speech had been brought to my attention, and as I was sure that a gentleman of his position never could have made it in the words reported, I desired to ascertain the facts from him.He said he had been wholly misrepresented.“Well,” I said, “I supposed so, and I rely upon you to correct that matter by having the report withdrawn, or, if that cannot be done, by making some explanatory statement.” He said he certainly would, and there the matter ended.I then reported to the commander of the Department of the East, General Dix, and he issued an order that I was in command of the troops sent to preserve the peace in the State of New York.I suggested to him that he should put me in command of the military district comprising the States of New York and New Jersey, as he had command of the whole department, but he expressed a disinclination so to do, and I, after a conference, yielded and said I would report to the Secretary of War for orders, but that I hope it would not be necessary. I asked him how many regulars could be spared from the garrison on Governor’s Island. He said he thought he could let me have five hundred men. I told him they might as well remain in the garrison as anywhere.8

The appointment had a psychological as well as military effect. “The assignment of Butler to the command of the federal soldiers stationed in New York State increased the ire of the Democrats,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer.9 As he prepared for Election Day, Butler wrote that he “issued my General Order No 1, in which I made it plain that there were several thousand secessionists in New York. They were there in such numbers as to impede the Union men getting lodgings and boarding-house accommodations, the landlords saying that they could let all the room they had to Southerners at their own prices. I took care that the Southerners should understand that means would be taken for their identification, and that whoever of them should vote would be dealt with in such a manner as to make them uncomfortable. That was sufficient, and substantially no Southerners voted at the polls on election day.”10

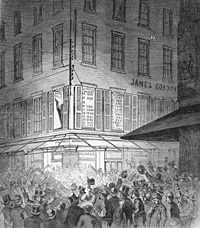

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Election Day was filled with anxiety and tension in the largest cities, especially in New York, where memories of riots mingled with warnings of coming incendiarism that Secretary Seward helped circulate. This incendiarism would become a reality on November 25-26, when eight men sent by Jacob Thompson, that egregiously unprincipled member of Buchanan’s cabinet now plotting in Canada, made a futile effort to state blazes in the St. Nicholas, Fifth Avenue, Metropolitan, St. James, and Belmont Hotels, the Astor House, and four others; their mixtures of camphene and phosphorous smoldering feebly and going out while firebells clanged. Barnum’s Museum had a fire and there were alarms in two theaters. But on November 8, fog and rain beset the long lines that waited patiently in the streets to deposit their ballots. The grog-shops were tightly closed, and disorder was unknown, save for a little street-fight in one ward. Hardly a soldier could be seen, and the police kept a quiet mien. General Dix, commanding the department, had of course taken full precautions. The Hudson and the East River were lined with vessels full of troops which could be landed at any point if needed, and the armories held detachments armed with bayonets. August Belmont’s vote was challenged on the ground that he had laid bets upon the election! When night fell people began thronging to the hotels and newspaper offices, still quiet and orderly.”11

Butler biographer Dick Nolan wrote that General Butler managed to keep the election peace “without difficulty or incident, aside from a number of assassination threats, which Butler ignored and which came to nothing. New York conducted the quietest election in its history, so that even the most timid of Lincoln’s supporters found no excuse to stay away from the polls.”12

Butler later wrote: “Early in the morning of the 8th, of November, election day, I despatched trusty officers to each point where dispositions had been made, to keep the peace and to meet violence, if necessary. I remained at my office to receive reports of the occurrences. The remainder of the day, until the polls closed, was monotonously quiet. The sixty lines of wire brought into the room adjoining my office such messages as these, repeated every hour without variation: ‘All quiet in No. 10;’ ‘All quiet in No. 25,’ and so on, as the case might be.” Wrote Butler: “That evening until a late hour was hilariously spent in listening to the good news of the election returns, and I went to bed with the reflection that loyalty to law and order had prevailed.”13

Butler wasn’t alone in his satisfaction. “So this momentous day is over, and the battle lost and won. We shall know more of the result tomorrow. Present signs are not unfavorable. Wet weather, which did not prevent a very heavy vote. I stood in queue nearly two hours waiting my turn,” wrote New York attorney George Templeton Strong. “This election has been quiet beyond precedent. Few arrests, if any, have been made for disorderly conduct. There has been no military force visible. It is said that portions of the city militia regiments were on guard at their armies, and that some 6,000 United States troops were at Governor’s Island and other points outside the city, but no one could have guessed from the appearance of the streets that so momentous an issue was sub judice….” Strong ended his diary entry: “VICTORIA! Te Deum laudamus. Te Dominum confitemur.”14

Despite all the energy which Mr. Lincoln put into New York, the results were disappointing. Historians John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo noted: “Lincoln received only 33.22% of the vote in New York City, although he earned 50.46% in the state as a whole. Most striking is the fact that of the nineteen major cities in the North, only Milwaukee (31.59%) gave a smaller percentage of its votes to Lincoln.”15 Mr. Lincoln clearly needed the support of Union soldiers for his Union ticket. “Although those in the federal military service voted this year, Lincoln won New York by less than 7,000 and Fenton by less than 9,000,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “The astonishingly large Democratic vote was probably due in part to the very numerous pre-election naturalizations in New York City; and perhaps, the Tribune‘s accusations of wholesale frauds in the lower wards were not unfounded. Nevertheless, that the administration had lost strength in 1864 over that in 1860, while the Democratic vote for McClellan was about 60,000 more than that cast for the fusion electors in 1860.”16

Nevertheless, historian David E. Long concluded: “The Empire State was probably the most pleasant surprise for Unionists in 1864. Though it had voted Republican in 1860 by more than 48,000, the tremendous influx of Irish immigrants had added a sizable Democratic voting bloc by 1864. Lincoln fared poorest in the largest cities. New York City went against him two to one, and in Kings, Albany, and Erie Counties, he trailed McClellan by 8,000. The soldier ballots from New York were not tabulated separately, but with more than 70,000 soldiers casting absentee ballots, they had to give him well in excess of his 6,750-vote margin of victory. Lincoln’s coattails proved long in New York as Union candidates won every state office.”17

General Butler was subsequently treated by grateful New Yorkers to a celebratory dinner that fed rumors about his own presidential ambitions. It was the zenith of Butler’s military career. Butler blamed his problems with Grant and eventual removal from Army command to this banquet at which Butler’s name was proposed for President in 1868. He wrote in his memoirs: “The fact that at a meeting at the Fifth Avenue Hotel which was represented to him as having been gotten up by my friends for that very purpose, I had been nominated for the presidency, was impressed upon General Grant’s mind by officers of his staff, as showing that I was there afterwards a positive rival. Nothing could have been further from the truth. But still it had an effect upon his mind, and from that hour until after he was President no kindly word of friendship ever passed from his lips to my ear.”‘18

Butler said a few days after the election that former Secretary of War Simon Cameron visited him in New York after the election to ask if he would be willing to replace Secretary of War Stanton. Butler told him that he wanted to stay in a military command. “Mr. Cameron said he had had a personal conversation with the President upon this subject, and that he was very sure that he would regret my determination.”19 Butler himself may have regretted his decision — by early 1865, he had been completely removed from any Union military command by General Grant.

Footnotes

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 64-65.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, (419).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 436-437.

- Dick Nolan, Benjamin Franklin Butler: The Damnedest Yankee, p. 310.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 753.

- Dick Nolan, Benjamin Franklin Butler: The Damnedest Yankee, p. 310.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 756.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 756-759.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 438.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 758.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory 1864-1865, p. 138-139.

- Dick Nolan, Benjamin Franklin Butler: The Damnedest Yankee, p. 310.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 770.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 510 (November 8, 1864).

- John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo, “The President and the Press: Lincoln, James Gordon Bennett and the Election of 1864”, The Lincoln Herald, Summer 1974, p. 68.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 439-440.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, p. 257.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 850.

- Benjamin F. Butler, Butler’s Book, Volume II, p. 769.

Visit

Benjamin Butler (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John A. Dix

John A. Dix (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Ulysses S. Grant (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Ulysses S. Grant (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)