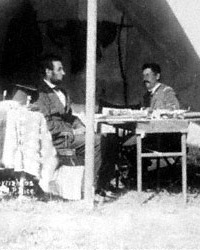

Abraham Lincoln and General George B. McClellan

Ticket Booths – Voters Procuring Tickets

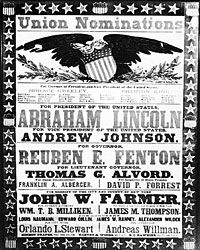

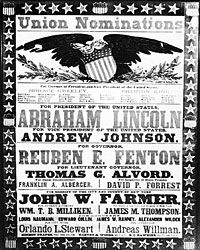

Poster from Lincoln’s 1864 campaign in New York

Map of the Presidential Election of 1864

I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest…

How Columbia receives McLellan’s Salutation from the Chicago Platform

Behind the scenes

Grand banner of the radical democracy, for 1864

Union and Liberty! and Union and Slavery!

The True Issue or ‘That’s What’s the Matter’

New York Congressman John Cochrane

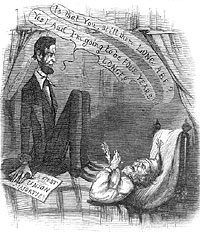

Jeff Davis’s November Nightmare

The artist portrays a President tormented by nightmares of defeat in the election of 1864

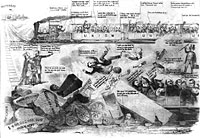

The Abolition Catastrophe, or the November smash-up

Lincoln Biographer Benjamin Thomas recalled “the cabinet member who, returning from New York, informed the President of the discouraging state of politics there. Pacing grimly back and forth across the room, Lincoln finally observed: ‘Well, it is the people’s business, — the election is in their hands. If they turn their backs to the fire and get scorched in the rear, they’ll find they have got to sit on the blister.”1 President Lincoln moved somewhat reluctantly when it came to his renomination and reelection. He told presidential aide John Hay in late October 1863: “I wish they would stop thrusting that subject of the Presidency into my face. I don’t want to hear anything about it. The Republicanof today has an offensive paragraph in regard to an alleged nomination of me by the mass meeting in New York last night.”2

Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase’s lieutenants, like John A. Stevens, Jr., were hard at work. But the same divisions among New York Republicans that afflicted President Lincoln also afflicted Chase. Historian Ernest A McKay wrote that “within this close group of New York dissidents there were jealousies and personal relations that required delicate handling. Stevens knew the value of [Horace] Greeley in helping him advance his political plans, but he also knew Greeley’s weaknesses. The editor was good on broad policy, Stevens told a Chase friend, but he was not a man for detail or executive management. He was also indiscreet and a poor judge of men, ‘the prey of political sharpers and innocent as a lamb.'”3 Historian William Frank Zornow wrote:

“When the [Union League] met in Washington early in December [1863], there was more than a little possibility that it would seek to dominate the coming presidential election. In New York, John Austin Stevens was working diligently to transform the powerful club there into a Chase society. Thurlow Weed discovered, or at least suspected, that the ‘Loyal Leagues…are fixing to control delegate appointments for Mr. Chase.’ The radical tendencies of the league had become well known, and it was generally felt that the meeting would be the signal for a general attack on Lincoln and his policies.

The assembly gathered in Washington on the appointed day. The President’s message had already been delivered and no effort had as yet been made to attack him. Perhaps the Unconditionals wished to consult together first at the league meeting before they opened their fusillade against Lincoln. The meeting was filled with Lincoln’s enemies; in glancing down the list of delegates, one cannot help feeling that he is raiding a roster of Chase supporters, many of whom were treasury agents. Though Unconditionals were present from every corner of the North, the attack on the President was milder than one would expect. After discussing fully the Missouri and reconstruction problems, the delegates adjourned to meet ‘at the same place and about the same time as the Republican National Convention.'”

Mark Howard was enthusiastic about the outcome of the league session at Washington. He felt confident the delegates preferred Chase for the Presidency, and he wrote to the Secretary that ‘the spirit of our Grand Council was fully in harmony with yours. Another treasury agent at the meeting reported that a radical spirit prevailed at the meeting and among the league in general. The league would ‘make the sentiment which would at least define the character of the nominee,’ he confided. Lincoln was not up to their stand,’ and ‘they appreciated the demand of the future for a government and would not be satisfied with our [and he used a pet Chasism] administration of Departments.'”4

Horace Greeley biographer James M. Trietsch wrote: “With the possibility that both the regular and the bolting Republicans would drop their candidates in favor of another man, the hopes of Chase and his followers rose once more. News arrived in the middle of August, at probably the most despairing moment of the war, that a movement had been launched to persuade Lincoln voluntarily to abdicate his nomination, or, if he refused, to eject him forcibly from the contest. The insurrection possessed a far more formidable sponsorship than such a proceeding would seem to have deserved. Its leader was David Dudley Field of New York whose brother, Stephen J. Field, Lincoln had a short time before appointed to the United States Supreme Court. Furthermore, Field’s most active co-worker was that same George Opdyke whose name has several times appeared here as one of the chieftains of the anti-Weed-Seward faction of Republicans in New York State.”5

Chase, however, did not control the New York Republican organization. On January 23, 1864 the Union Central Committee of New York recommended renomination of Mr. Lincoln without objection. By February 3, Gideon Welles recorded in his diary: “Almost daily we have some indications of Presidential aspirations and incipient operations for the campaign. The President does not conceal the interest he takes, and yet I perceive nothing unfair or intrusive.”6

Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole wrote Interior Secretary John P. Usher in late February : “I have been looking over the political field here very industriously since my arrival — and find that there is considerable of opposition to Mr Lincoln The Indipendent [sic] folks except [Henry Ward] Beecher are for Chase[.] [Theodore] Tilden the Editor says he is not against Mr Lincoln But prefers Mr Chase as more likely to push forward the war & abolish slavery — says he will not engage in any fight against the President & is for his nomination next to Chase— The next in importance is Ex Mayor Opdyke — he is openly for Chase and active in his support— At a Dinner yesterday — when ten or twelve were present they were divided as follows for Chase — Ex Mayor [George] Opdyke Judge White, Waldo Hutchins & Senator Wardsworth [sic] — for Mr Lincoln Jas T. Brady Judge Tyler — Raymond of the Times, Henry M. Tabor, L. W. Jannie & a Mr Riggs — non committal two or three— Those that were for the President — wanted the Cabinet — reorganized but would wait untill [sic] 4th March 1864 — provided they were assured that it would then be done”7

Dole, who frequently passed on political intelligence to President Lincoln, added in his characteristically rambling style : “Last night I met at the Union Club Rooms some of the solid men of New York viz Mr Taylor Moses H Grinnell several of the Bank Presidents — and Bank cashiers — amongst them the Prest & Cashr of the Bank of Commerce Simeon Draper — &c &c They are unconditional[l]y for Mr Lincoln But agreed in saying that all or nearly all of the patronage of the City was against them & for Sec Chase and that Mr Barney must go out or the City was Lost to us — all agree that Barney must go out & I believe that a majority perhaps a Large Majority agree that the present Post Master here should have the place — a few are for Mr Draper — he did not mention it to me But the radicals & the Weed men agree in a great degree upon the Post Master — and as this is a compromise — I have no doubt that it is best. Wm A. Darling Prest of the 3d Ave R. R. and Late Lincoln Elector — called upon me with Mr Keifer Late recorder of this city— They agree that if the P. M. Mr Wakeman is at once put in the Collectors office that he can & will secure the City for Mr Lincoln and that without this it is at Least very doubtful— Of course all these sayings must be taken with some allowance But it is clearly the opinion of the people here who want office that the way to get it is to be for Mr Chase and so soon & that idea is disapated [sic] these factions will be for Mr Lincoln and it may be that others than Mr Barney should go over I have been very careful in what I have said, think I have done good. The friends of Mr Lincoln thi[nk] so or say so at Least I have pointed out the dificulties [sic] in the way of the Prest doing all they ask & have I think convinced some of our friends that they are asking to much— all agree that Mr Lincoln can make no present change in his Cabinet or any promises for the future & yet they want to feel that it will be done— I have said to them that my understanding is that Mr Lincoln if reelected will be relieved of any embarrassment by the tender of resignations, by the principle office Holders at Washington & that he would of course reap[p]oint only such as should be satisfactory to himself & the country I know this is your view of what is proper & it is mine-“8

New York being New York, sometimes Republicans got along better with other Democrats than with Republicans. “The course of Thurlow Weed and some New York politicians has been singular,” wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles in his diary on May 11. Montgomery “Blair took from his pocket a letter from [S.L.M.] Barlow of New York, a Copperhead leader, with whom, he informs me, he has corresponded for some weeks past. Barlow is thick with General [George B.] McClellan, and Blair, who has clung also to McC., not giving him up until his Woodward letter betrayed his weakness and ambition, still thought he might have military service, provided he gave up his political aspirations. It was this feeling that had led to the correspondence.”

Continued Welles: “I do not admire the idea of corresponding with such a man as Barlow, who is an intense partisan, and Blair himself would distrust almost any one who should be in political communication with him. Blair had written Barlow that he would try to get McC. an appointment to the army, giving up party politics. Barlow replied that no party can give up their principles, and quotes a letter which he says was written by a distinguished member of Mr. Lincoln’s Cabinet last September, urging the organization of a conservative party on the basis of the Crittenden compromise. This extract shocks Blair. He says it must have been written by [William H.] Seward. I incline to the same opinion, though [Interior Secretary John P.] Usher crossed my mind, and I so remarked to Blair. Last September U.’s position was more equivocal than Seward’s, and he might have written such a letter without black perfidy. Seward could not.”9

The situation in New York was complicated by the nomination of John C. Fremont for President on a ticket with former New York congressman John Cochrane as his vice presidential running mate.

Navy Secretary Welles described Cochrane as “wayward and erratic. A Democrat, a Barnburner, a conservative, an Abolitionist, an Anti-abolitionist, a Democratic Republican, and now a radical Republican. He has some, but not eminent, ability; can never make a mark as a statesman.”10 Navy Secretary Welles described Fremont’s supporters as “a heterogeneous mixture of weak and wicked men. They would jeopard[ize] and hazard the Republican and Union cause, and many of them would defeat it and give success to the Copperheads. He is blamed for not being more energetic and because he is despotic in the same breath. He is censured for being too mild and gentle towards the Rebels and for being tyrannical and intolerant. There is no doubt he has a difficult part to perform in order to satisfy all and do right.”11

In New York it was one thing to arrange the candidate, it was another to arrange the patronage. It was still another to arrange for the patronage employees to contribute to the campaign’s coffers. The rough style of the campaign fund-raising had not improved a much by the end of August, 1864. Welles wrote that New York Postmaster Abram Wakeman “has called upon me several times in relation to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He is sent by [Henry J.] Raymond, by Humphrey, by [Robert.] Campbell and others, and I presume Seward and Weed have also been cognizant of and advising in the matter. Raymond is shy of me. He evidently is convinced that we should not harmonize. Wakeman believes that all is fair and proper in party operations which can secure by any means certain success, and supposes that every one else is the same. Raymond knows that there are men of different opinion, but considers them slow, incumbrances [sic], stubborn and stupid, who cannot understand and will not be managed by the really ready and sharp fellows like himself who have resources to accomplish almost anything. Wakeman has been prompted and put forward to deal with me. He says we must have the whole power and influence of the government this coming fall, and if each department will put forth its whole strength and energy in our favor we shall be successful. He had just called on Mr. Stanton at the request of our friends, and all was satisfactorily arranged with him. Had seen Mr. [William P.] Fessenden and was to have another interview, and things were working well at Treasury. Now the Navy Department was quite as important as either, and he, a Connecticut man, had been requested to see me. There were things in the Navy Yard to be corrected, or our friends would not be satisfied, and the election in New York and the country might by remissness be endangered. This must be prevented, and he knew I would use all the means at my disposal to prevent it. He then read from a paper what he wanted should be done. It was a transcript of a document that had been sent me by Seward as coming from Raymond for the management of the yard, and he complained of some proceedings that had given offense. Mr. Halleck, one of the masters, had gathered two or three hundred workmen together, and was organizing them with a view to raise funds and get them on the right track, but Admiral Paulding had interfered, broken up the meetings, and prohibited them from assembling in the Navy Yard in the future.”12

“I told him I approved of Paulding’s course; that there ought to be no gathering of workmen in working hours and while under government pay for party schemes; and there must be no such gatherings within the limits of the yard at any time. That I would not do an at myself that I would condemn in an opponent. That such gatherings in the government yard were not right, and what was not right I could not do,” wrote Welles.13

Although Welles himself was not representative of what the Republican organization was doing, Welles was an invaluable chronicler of what the organization was doing. A few weeks later, Welles was still complaining to his diary of Raymond’s actions: “This fellow, trained in the vicious New York school of politics, is Chairman of the Republican National Committee; is spending much of his time in Washington, working upon the President secretly, trying to poison his mind and induce him to take steps that would forever injure. Weed, worse than Seward, is Raymond’s prompter, and the debaucher of New York politics.”14 The next day, a delegation led by the Illinois State Republican Chairman, called on Welles, “complaining in general terms that the employés of the Brooklyn Navy Yard were, a majority of the, opposed to the Administration.” As usual, Welles defended the administration of the Navy Yard and its isolation from political pressures.15

“The victory of [Philip H.] Sheridan has a party-political influence,” wrote Gideon Welles of Sheridan’s victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek in the Shenandoah Valley on October 19, 1864. “It is not gratifying to the opponents of the Administration. Some who want to rejoice in it feel it difficult to do so, because they are conscious that it strengthens the Administration, to which they are opposed. The partisan feeling begins to show itself strongly among men of whom it was not expected. In New York there has been more of this than elsewhere.”16

Welles returned to his complaints about New York on October 13: “The President is greatly importuned and pressed by cunning intrigues just at this time. Thurlow Weed and Raymond are abusing his confidence and good nature badly. Hay says they are annoying the President sadly. This he tells Mr. Fox, who informs me. They want, Hay says, to control the Navy Yard but dislike to come to me, for I give them no favorable response. They claim that every mechanic or laborer who does not support the Administration should be turned out of employment.”17 Prospects of employment, patronage and victory seemed to pull the New York Republican Party together.

New York Secretary of State Chauncey M. Depew later wrote: “It is difficult now to recreate the scenes of that campaign. The people had been greatly disheartened. Every family was in bereavement, with a son lost and others still in the service. Taxes were onerous and economic and business conditions very bad. Then came this reaction, which seemed to promise an early victory for the Union. The orator naturally picked up the phrase, “The war is a failure”; then he pictured Farragut tied to the shrouds of his flag ship; then he portrayed Grant’s victories in the Mississippi campaign, Hooker’s “battle above the clouds,” the advance of the Army of Cumberland; then he enthusiastically described [General Philip H.] Sheridan leaving the War Department hearing of the battle in Shenandoah Valley, speeding on and rallying his defeated troops, reforming and leading them to victory, and finished with reciting some of the stirring war poems.”18

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, “Lincoln’s Humor” and Other Essays of Benjamin Thomas, p. 13.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 104 (October 30, 1863).

- Ernest A. McKay, The Civil War and New York City, p. 235-236.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 32-33.

- James M. Trietsch, The Printer and the Prince, p. 275.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 521 (February 2, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 28-29 (May 11, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 43 (June 1, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 43 (June 1, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 122-123 (August 27, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 122 (August 27, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 142 (September 13, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 143 (September 14, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 153 (September 20, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William P. Dole to John P. Usher, February 20, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William P. Dole to John P. Usher, February 20, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 175 (October 13, 1864).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 64-65.

Visit

Samuel L. M. Barlow

James Gordon Bennett

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William Cullen Bryant

Salmon P. Chase (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

David Dudley Field

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George Opdyke

Henry J. Raymond

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Abram Wakeman

Thurlow Weed

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Gideon Welles (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)