President Lincoln briefly visited New York in late June 1862 when he visited General Winfield Scott at West Point to discuss the military strategy of General George B. McClellan. “The president sought his counsel on the important question of whether to risk weakening Washington’s defenses to reinforce McClellan,” wrote Scott biographer Timothy D. Johnson. “The general’s opinion, as he reiterated later in writing, was that ‘the defeat of the rebels, as Richmond, or their forced retreat, thence,…would be a virtual end of the rebellion.”1

McClellan had failed to order sufficient forces to protect the capital when he left the Washington area for the Jamestown Peninsula in order to attack Richmond. When President Lincoln learned of the deception from General James Wadsworth, he ordered that the corps led by General Irvin McDowell held in the Washington area. On May 24, 1862, President Lincoln wired General McClellan: “In consequence of Gen. Banks’ critical position I have been compelled to suspend Gen. McDowell’s movement to join you. The enemy are making a desperate push upon Harper’s Ferry, and we are trying to throw Fremont’s force & part of McDowell’s in their rear.” McDowell’s 40,000-man force was used in the campaign President Lincoln launched against Confederate General Stonewall Jackson — to little effect. McClellan, who always believed he was outnumbered by the enemy, was infuriated by President Lincoln’s actions and believed it crippled his military plans. At West Point, President Lincoln talked to Scott of sending McDowell’s force to McClellan’s aid, and Scott endorsed the move.

Popular opinion came up with other explanations for the President’s trip to West Point — which was necessitated by the ill-health of the corpulent general. Even when he had been the general-in-chief of the army, Scott’s weight and illness sometimes prevented him from getting out of his carriage at the White House. New York attorney George Templeton Strong: “Faint-heartedness still prevails. The President’s visit to General Scott at West Point has stimulated the production of most authentic reports and reliable statements, mostly ‘asthenic’ and unfavorable. Today’s crop has been erroneous; for example, ‘McClellan is dead.’ ‘He is not dead yet, but dying of dysentery with typhoid symptoms.’ ‘A.B. was told by C.D. that he has a letter from his cousin, Major X.Y. on General Z.’s staff, stating that our McClellan has lost his mind and gone crazy with anxiety and excitement.’ ‘Lincoln wants Scott’s advice about McClellan’s successor.'”2 Much later, relatives of Rev. Henry Ward Beecher suggested President Lincoln was in the habit of visiting the Brooklyn preacher at night — and that this one such occasion (an impossibility given the timing of the visit).

According to Scott biographer John S. D. Eisenhower, it was Scott who took the initiative on the issue. “During this visit by the President, Scott seized the opportunity to recommend that Major General Henry W. Halleck be appointed general-in-chief of the Army to replace McClellan, the field commander. Lincoln assented, and shortly afterward brought Halleck to Washington with that title. Lincoln may not have been satisfied with Halleck’s later performance. In addition, his own self-confidence in his role as commander-in-chief was growing. In any case, Lincoln did not seek Scott’s advice again; indeed, this was the last time Scott would ever see Lincoln alive.”3 Within days, President Lincoln recalled Halleck from his western command and installed him as general-in-chief of the army — a position which McClellan had held from November 1861 to March 1862.

There was an air of mystery about the President’s journey as reported in the New York Tribune, June 24,1862: “It is stated on the authority of passengers from West Point today that President Lincoln and General [John] Pope arrived at Cozzens Hotel, West Point, at an early hour this morning, and the fact that a special train passed over the Hudson River Railroad after midnight leaves little reason to doubt the truth of the report. As General Scott is now residing at West Point it is to be presumed that the President and General Pope have gone to consult him in regards to affairs of the army. From another source we learn that the President, accompanied by Colonel D.C. McCallum, military superintendent of railroads, left Washington at 4:10 P.M. yesterday, arriving here at 1:30 A.M. Leaving at 2 A.M. by the Hudson River Railroad, he reached West Point at 3:10.”4

Pennsylvania Republican Alexander K. McClure often visited the White House and spoke to Mr. Lincoln about political and military matters, but he later wrote that President Lincoln’s “visit to West Point startled the country and quite as much startled the Cabinet, as not a single member of it had any intimation of his intended journey. What passed at the interview between Lincoln and Scott was never known to any, so far as I have been able to learn, and I believe that no one has pretended to have had knowledge of it. It is enough to know that [General John] Pope was summoned to the command of a new army, called the Army of Virginia, embracing the commands of [John C.] Fremont, [Nathaniel] Banks, and [Irvin] McDowell, and that Halleck was made General-in-Chief.”5

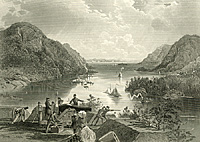

Lincoln chronicler Ralph Gary wrote that Mr. Lincoln traveled up the East Side of the Hudson River after taking the ferry from Jersey City to New York City. At Garrison, he took another ferry west across the river to West Point: “Lincoln inspected guns at Storm King Mountain on the Hudson River near West Point. The inventor Colonel Robert P. Parrott fired across the river. Lincoln was not impressed and said, ‘I’m confident you can hit that mountain over there, so suppose we get something to eat. I’m hungry.” He also visited cadets at Fort Clinton, and met with ten whom he had appointed after becoming president.”6

Gary wrote: “The conference with Scott lasted about five hours, after which Lincoln inspected the apartments, barracks, and West Point foundry opposite the academy. A dinner party was held at the hotel in the afternoon. The president charmed all the ladies with his conversational powers and affability at a reception at the hotel that night. All along the route back to New York City the next day, people gathered to get a glimpse of the president. In spite of pleas for a speech, ‘the president could not see it.’ But after he had been ferried to Jersey City for the train back to Washington, the president consented to make a few informal remarks.”7 President Lincoln said:

When birds and animals are looked at through a fog they are seen to disadvantage, and so it might be with you if I were to attempt to tell you why I went to see Gen Scott. I can only say that my visit to West Point did not have the importance has been attached it; but it conceived [concerned] matters that you understand quite as well as if I were to tell you all about them. Now, I can only remark that it had nothing whatever to do with making or unmaking any General in the country. [Laughter and applause.] The Secretary of War, you know, holds a pretty tight rein on the Press, so that they shall not tell more than they ought to, and I’m afraid that if I blab too much he might draw a tight rein on me.”8

On June 25, the New York Tribune reported: “President Lincoln left West Point by special train on the Hudson River Railroad about 9 A.M. Arriving at the Thirty-first Street Station at 10 A.M. he was met by Colonel McCallum and conveyed in a carriage to the Jersey City Ferry, where he took a special train at 11 o’clock for Washington over the New Jersey Central Railroad.”9 The visit was a quick one — Mr. Lincoln arrived back in Washington on June 25 — two days after he had left. Meanwhile, Scott himself had prepared a brief memorandum of his ideas:

The President having stated to me, orally, the present numbers & positions of our forces in front of the rebel armies, south & South west of the Potomack, has done me honor to ask my views, in writing, as to the further dispositions now to be made, of the former, towards the suppression of the rebellion, & particularly of the army under McDowell, towards the suppression of the rebellion.Premising that, altho’ the statements of the President were quite full & most distinct & lucid — yet from my distance from the scenes of operation, & not having recently followed them up, with closeness — many details are still wanted to give professional value to my suggestions— I shall, nevertheless, with great deference, proceed to offer such as most readily occur to me — each of which has been anticipated by the President.I consider the numbers & positions of [John C.] Fremont & [Nathaniel] Banks, adequate to the protection of Washington against any force the enemy can bring by the way of the Upper Potomack, & the troops, at Manassas junction, with the garrisons of the fort on the Potomack & of Washington, equally adequate to its protection on the South.The force at Fredericksburg seems entirely out of position, & it cannot be called up, directly & in time, by McClellan, from the want of rail-road transportation, or an adequate supply train, moved by animals. If, however, there be a sufficient number of vessels, at hand, that force might reach the head of York river, by water, in time to aid in the operations against Richmond, or in the very improbable case of disaster, there, to serve as a valuable reinforcement to McClellan.The defeat of the rebels, at Richmond, or their forced retreat, thence, combined with our previous victories, would be a virtual end of the rebellion, & soon restore entire Virginia to the Union.The next remaining important points to be occupied, by us, are — Mobile, Charleston, Chattanooga. These must soon come into our hands.McDowell’s force, at Manassas, might be ordered to Richmond, by the Potomack & York rivers, it & be replaced, at Manassas, by King’s brigade, if there be adequate transports at, or near Alexandria.10

Footnotes

- Timothy D. Johnson, Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory, p. 240.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 233 (June 25, 1862).

- John S. D. Eisenhower, Agent of Destiny: The Life and Times of General Winfield Scott, p. 403.

- John W. Starr, Jr., “Did Lincoln and Beecher Pray Together?”, p. 4 (Reprinted from Christian Advocate, April 22, 1926).

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 183-184.

- Ralph Gary, Following in Lincoln’s Footsteps: A Complete Annotated Reference to Hundreds of Historical Sites Visited by Abraham Lincoln, p. 273.

- Ralph Gary, Following in Lincoln’s Footsteps: A Complete Annotated Reference to Hundreds of Historical Sites Visited by Abraham Lincoln, p. 273.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume V, p. 284 (June 24, 1862).

- John W. Starr, Jr., “Did Lincoln and Beecher Pray Together?”, p. 4 (Reprinted from Christian Advocate, April 22, 1926).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Winfield Scott to Abraham Lincoln, June 24, 1862).