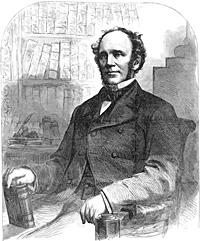

Horatio Seymour was “tall, fine-looking, of an imposing figure with a good though colorless face, bright, dark eyes, a high, commanding forehead, dark-reddish hair, and slightly bald. He had a clear, ringing voice, with a slight imperfection in his speech, and he was in the main an attractive and effective speaker, and a capital presiding officer. His opening address, which was very calm and cool, was not well received by the crowd, who evidently wanted something more heart-firing,” wrote journalist Noah Brooks of Seymour’s role as presiding office of the 1864 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.1

Seymour had his attractive qualities. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Even the abolitionist Gerrit Smith admitted that he was a gentleman of wide reading, winning manners, and pure life. Essentially a moderate, before the war he had opposed nativism and prohibition, and had denounced Northern and Southern firebrands with equal fervor. He was hard-working, conscientious, and talented. But he was fiercely hostile to the more advanced Administration measures: to attacks on slavery, the confiscation laws, the draft, and all restrictions upon civil rights.”2 Historian William B. Hesseltine described Seymour as “a lawyer, dairy-farmer, speculator in Wisconsin timber lands, and politician of the ‘Marcy’ wing of the New York Democracy. Seymour was gentle in speech, moderate in manner, temperate in his judgments as in his habits. He had more than an amateur’s interest in science, keeping a ‘polar microscope,’ a telescope, and sundry scientific apparatus in the front parlor of his Utica home.”3

Well-read and charming, opinionated but indecisive, Seymour did not really enjoy the political wars. Historian William B. Hesseltine wrote that “his personality inspired confidence: he seldom smoked, rarely drank wine, yet was no puritan. He was a cultured Christian gentleman — a type rare in politics, and a godsend to a Democratic opposition that sorely needed respectable leadership. Yet, as it turned out, Seymour’s dignity, culture, personality, integrity, and oratory would not prevail against the shrewd and persistent ‘smear’ tactics of the administration.”4

English journalist William Howard Russell, who met Seymour in March 1861, observed in his diary: “Mr. Seymour is a man of compromise, but his views go farther than those which were entertained by his party ten years ago. Although Secession would produce revolution, it was, nevertheless, ‘a right,’ founded on abstract principles, which could scarcely be abrogated consistently with due regard to the original compact.”5 Russell wrote: “I do not think that any of the guests sought to turn the channel of talk upon politics, but the occasion offered itself to Mr. Horatio Seymour to give me his views of the Constitution of the United States, and by degrees the theme spread over the table. I had bought the ‘Constitution’ for three cents in Broadway in the forenoon, and had read it carefully, but I could not find that it was self-expounding; it referred itself to the Supreme Court, but what was to support the Supreme Court in a contest with armed power, either of Government or people? There was not a man who maintained the Government had any power to coerce the people of a State, or to force a State to remain in the Union, or under the action of the Federal Government; in other words, the symbol of power at Washington is not at all analogous to that which represents an established Government in other countries. Although they admitted the Southern leaders had mediated the treason against the Union’ years ago, they could not bring themselves to allow their old opponents, the Republicans now in power to dispose of the armed force of the Union against their brother democrats in the Southern States.”6

When Seymour was nominated for Governor in 1862, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote that he “has smartness, but not firm, rigid principles. He is an inveterate partisan, place-hunter, fond of office and not always choice of means in obtaining it. More of a party man than patriot. Is of the Marcy school rather than of the Silas Wright school, — a distinction well understood in New York.”7 Seymour trained in the legal and military arts but practiced neither, instead serving first as an aide to Governor William Marcy and then as legislator from upstate New York.

Seymour’s sister was married to Republican Congressman Roscoe Conkling. Conkling biographer David M. Jordan wrote: “Horatio was the antithesis of the young Republican his little sister brought into the family; he was dignified, possessed of an easy culture, courteous, and gracious; he was nineteen years older than Conkling, and he was to find his brother-in-law a constant, even ostentatious, opponent. Seymour was strongly opposed to his sister’s marriage; later developments show how much wiser Julia would have been to listen to the governor’s advice.”8 (Conkling wouuld engage in a notorious affair with Katherine Chase Sprague, daughter of Lincoln’s first Secretary of the Treasury.)

“Governor Seymour was a patriot, but not a statesman of the higher type. It is true that he did not fulfill the direst predictions of his opponents by refusing support to the national government. He did not resort to violence in protecting state rights. But he was perilously near to that,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer.9 Biographer Stewart Mitchell was more admiring. Historian James G. Randall wrote: “In the excellent biography by Stewart Mitchell [Seymour] stands forth as a consistent personality and a man of distinction — a conservative Democrat whose service went back to the ‘Albany Regency’ days of Van Buren, eminently respectable, believing in the Democratic party, content with the ‘good life,’ distrustful of reformers, devoted to the Burkian concept of the expedient as the guiding rule of statesmen. This, together with his temperament, explained why he had never joined the crusade against slavery.”10

According to Randall, “Amid the divisive tendencies of the New York Democrats — to say nothing of their opponents, the Whigs and later the Republicans — Seymour had adhered to the ‘Hunker’ (or less democratic) wing of the party, and had served his state as assemblyman, speaker of the house, and governor in prewar years. In 1860 he had enough prominent mention in connection with the Charleston convention (which he did not attend) to enable his biographer to speculate as to the possibility that he might then have become the nominee of a united Democratic party. Though this should not be taken too seriously, it is presented as one of those fascinating ‘ifs’: ‘a two-man contest between Abraham Lincoln and Horatio Seymour might have changed the course of American history.’ 2 In that campaign Seymour favored Douglas and in the election of that year he honestly regretted the minority-won success of a sectional party.”11

But Seymour was scarcely consistent. “It was Horatio Seymour, it appears, who drew up the call for the famous convention held at Tweddle Hall in Albany early in 1861. The Crittenden Compromise having failed in the Congress, the resort to this convention of moderate men was his second definite move to do what he could to check secession and avert the Civil War. His speech at that gathering on January 31, 1861, is a plea directed to the North rather than the South,” wrote biographer Stewart Mitchell.12 “Seymour ended his address at Tweddle Hall by asking for ‘an appeal to the Republicans and to the Legislature of this State, to submit the proposition of Senator Crittenden to the vote of the people of New York.'”13

At a convention of State Democrats in early February 1861, Seymour spoke on behalf of the South: “All virtue, patriotism, and intelligence seem to have fled from our National Capitol; it has been well likened to a conflagration of an asylum for madmen — some look on with idiotic imbecility, some in sullen silence, and some scatter the firebrands which consume the fabric above them, and bring upon all a common destruction.”14 He added that Southerners were justified in at “their most bitter and unscrupulous assailants.”15

“Shortly after his speech for conciliation at Tweddle Hall in Albany, Seymour accepted the empty honor of standing as the candidate of the Democratic caucus for senator,” wrote biographer Mitchell.16 The Senate seat being vacated by William H. Seward went instead to Ira Harris, who was the compromise case of Republicans unable to choose between William Evarts, who was the candidate of Republican boss Thurlow Weed, and Horace Greeley, who was the anti-Weed candidate. Later in 1861, Seymour ran for Attorney General as a Democrat and lost to a War Democrat running on the Union ticket, Daniel S. Dickinson.

“Seymour always refused to consider any aspect of slavery a paramount issue: whether or not it was to be maintained, extended, or exterminated were questions subordinate to the peace and welfare of the whole people,” noted Mitchell.17“Possibly there was still another reason why Seymour never joined the crusade against slavery. His admiration for [Edmund] Burke had taught him to prize and to praise the expedient: he distrusted grand notions as thoroughly as he disliked big words.”18 Seymour spoke at the Democratic State Convention in Syracuse in September 1861. According Mitchell, Seymour maintained that slavery “was not the cause of the Civil War, or slavery had always existed in the land; it was present when the Union was formed, and the people had prospered before it became a matter of dispute. Causes and subjects of contention were frequently distinct: the main cause of the war was the agitation and arguments over slavery. At this point Seymour made a statement which was often to be used against him thereafter, for he hit the nail on the head and nicely: ‘If it is time that slavery must be abolished to save this Union then the people of the South should be allowed to withdraw themselves from that government which cannot give them the protection guaranteed by its terms.'”19 Seymour told the convention:

I shall not attempt to foreshadow the consequences of this war. I do not claim a spirit of prophecy. We have had too much of the irreverence that treats the finger of God like the fingers upon the guide-posts, and makes it pont to the paths which men wish to have pursued. But I believe that we are either to be restored to our former position, with the constitution unweakened, and the powers of the States unimpaired, and the fireside rights of our citizens duly protected, or that our whole system of government is to fail. If this contest is to end in a revolution; if a more arbitrary government is to grow out of its ruins, I do not believe that even then the wishes of ultra and violent men will be gratified. Let them remember the teachings of history. Despotic governments do not love the agitators that call them into existence. When Cromwell drove out from Parliament the latter-day saints and higher-law men of his day, and ‘bade them cease their vain babblings’; and when Napoleon scattered at the point of the bayonet the Council of Five Hundred, and crushed revolution beneath his iron heel, they taught a lesson which should be heeded this day by men who are animated by a vindictive piety or a malignant philanthropy.20

The 1862 campaign was in many ways a referendum on the Lincoln Administration’s war policies. General James Wadsworth was the Republican candidate against Seymour for the post Governor Edwin Morgan was vacating. The next year “Seymour’s speech to the convention at Albany accepting the [gubernatorial] nomination the day it was made was the first big gun of the campaign in New York State,” wrote biographer Stewart Mitchell. “Referring to his visit to Washington in the spring of 1862, he declared that every one who visited the capital ‘could see and feel we were upon the verge of disaster.’ Only in the camp of the soldiers could he find ‘devotion to our Constitution, and love’ of the flag. This was not time, in his opinion to let government continue unchecked by intelligent and active opposition. ‘Let the two great parties be honest and honorable enough to meet in fair and open discussion with well-defined principles and politics. Then each will serve our country as well out of power as in power. The vigilance kept alive by party contest guards against corruption or oppression.’ The Democrats he promised, had no desire to embarrass President Lincoln; they protested, in fact, against insubordinate and disrespectful abuse of him.”21

“From the mere party point of view, Seymour’s nomination was, perhaps, the strongest that could have been made then,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. His character, bearing, and antecedents were well suited to harmonize the various elements of the party, his veto of the Maine liquor bill during his previous term as governor brought to him the support of a most powerful interest, he was one of the most effective Democratic orators in the State, and he had the strength which naturally comes to a strict partisan with some political accomplishments. The Albany Evening Journal acknowledged that Seymour’s personal character was untarnished, and that the other Democratic candidates were personally unexceptional, having been hitherto in the public service without any serious fault being found with them. Thus, the Democrats entered upon the campaign with good prospects of success.”22 According to historian Allan Nevins, “The platform on which Seymour stood gave comfort to all enemies of the Administration and most sympathizers with the South, for it re-emphasized the Crittenden Resolution, and while pledging a hearty effort to suppress the rebellion, declared that the Democrats would endeavor to restore the Union as it was, and maintain the Constitution as it is.’ One plank denounced arbitrary arrests. Seymour, who was present, assailed emancipation as ‘a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, and of arson and murder, which would invoke the interference of civilized Europe.”23

It was a rough campaign — although General Wadsworth was away on military duties in Washington. Historian Nevins wrote of Seymour: “When nominated, he expected to meet defeat, but hoped to demonstrate the existence of a strong party which would oppose the forcible subversion of the white South and a reign of intolerance in the North. ‘I enjoy abuse at this time,’ he wrote his sister, ‘for I mean to indulge in it.’ Certainly his acceptance speech was abusive of the Administration. His unique combination of cultivated manners and acrid partisanship, of candor and casuistry, was always to make his course hard to understand.”24 Seymour wrote his family: “I do not care about my election. That is not probable. But I want the opponents of the bad men who have brought our country into its present deplorable condition to be so much aroused as to make themselves felt and respected. If this is done, we shall have a strong, compact party that can defy violence and keep fanatics in check. We live in a fighting world, and in times like these, they are most safe who take strong grounds and call around them strong friends.”25

According to Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell, “The campaign which followed was full of sound and fury. Once Richmond had dictated his act of sacrifice, Seymour threw himself into the fight for office with unusual vigor. He stumped the state from one end to the other — not a common practice in those days — declaring that the Union must be restored and the Constitution respected.”26 But Republican attacks on his patriotism took its toll. “The charges of the Republican-Unionists evidently told and put the Democrats on the defensive,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “Seymour devoted quite some attention to refuting some accusations. He affirmed that he was earnestly for the war. At the great Cooper Institute ratification meeting on October 13th, he asked why ‘those who supported their country’s cause were branded as traitors?’ He then defended his own record, saying that ‘he had addressed more meetings in support of the war than he would address in support of the ticket on which his name stood.”27

Civil liberties and the suspension of habeas corpus became a central campaign issue. “Horatio Seymour and other Democratic leaders hence met a large response from independent voters when they made the arrests a major issue of the fall campaign,” wrote historian Allan Nevins.28 Historian Stewart Mitchell noted: “In the autumn of 1862 the Democrats of New York City were united for the moment because their defeat in the mayoralty election of 1861 had robbed them of patronage, the perennial reason for their quarrels. As often as they held office they fell into feuds over the spoils. In 1862, however, the two great factions in the city composed their differences and put up a fusion ticket, backed by Nelson J. Waterbury of Tammany, and Fernando Wood of Mozart Hall. As a consequence of this truce Wood went to Washington as a representative in the Congress, and Seymour carried the city for governor by 31,309.”29 Seymour carried the state by approximately 10,700 votes.

Republican Chauncey M. Depew recalled that “Horatio Seymour made a brilliant canvass. He had no equal in the State in either party in charm of personality and attractive oratory. He united his party and brought to its ranks all the elements of unrest and dissatisfaction with conditions, military and financial. While General Wadsworth was an ideal candidate, he failed to get the cordial and united support of his party.”30 But it was not an unalloyed victory. Seymour himself wrote his sister: “I wish my troubles ended with the election. The result is very gratifying but I dread going to Albany again. I was about getting myself into comfortable home habits.”31 The Governor-elect wrote friend Samuel Tilden: “Now that you and others have got me into this scrape, I wish you would tell me what to do.”32

Biographer Mitchell wrote: “Seymour took his spectacular victory with decorum. Those who heard and read his speech at Utica on November 6 knew that he realized the darkness of the day which lay before him and the heavy responsibility which he would have to shoulder during the next two years. His task was the same as that of Lincoln — he must take care lest he perish between the two extremes of opinion. He would live and work at the centre of a triangle of hostile abolitionists, secessionists, and Copperheads.”33 Suddenly Seymour was the most important Democrat in the country — a fact immediately recognized by President Lincoln

In December 1862, Thurlow Weed was at the White House when President Lincoln asked him to deliver a message to Governor Horatio Seymour of New York: “Governor Seymour has greater power just now for good than any other man in the country. He can wheel the Democratic party into line, put down rebellion, and preserve the government. Tell him for me that if he will render this service to his country, I shall cheerfully make way for him as my successor.”34 Thurlow Weed said he went to Albany and repeated the conversation to Governor Seymour.35 Seymour, however, said he wanted to act “as an irreconcilable and conscientious partisan,” reported biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay, who thought Weed exaggerated President Lincoln’s intent.36 Moreover, the two Lincoln aides were not Seymour admirers.

According to historian Hesseltine, “Seymour heard the emissary in silence, giving no indication of his intended course. He did, however, look about for an adjutant general who would act in harmony with the national government. But he neither listened to Weed nor consulted Lincoln about his inaugural address. Instead, he sought advice from fellow Democrats and heeded their counsels to make his initial speech a ringing denunciation of the tendencies of the day. He would, he said in his first official utterance, strive ‘to maintain and defend the sovereignty and jurisdiction’ of New York.”37 Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “occupying a chair which before and after has served as a stepping-stone to the presidency, Seymour’s inaugural address and his message to the Legislature were naturally awaited with interest, not only in New York but also without. Would he render a hearty support to the war? Would he bring the State into conflict with the national administration?”38 Seymour tried in his inaugural to both advocate New York State’s rights and profess support for the federal government. According to biographer Stewart Mitchell, “When Seymour took office for the second time, he placed significant emphasis on the fact that he was taking two oaths on one and the same day: the first, to support the Constitution of the United States; and the second, to maintain the constitution of New York. To a ‘strict-construction’ Democrat, this double aspect of the office was important.”39 The new Governor said:

Fellow-citizens: In your presence I have solemnly sworn to support the Constitution of the United States with all its grants, restrictions and guarantees, and I shall support it. I have also sworn to support another Constitution — the constitution of the State of New York — with all its power and rights. I shall uphold it. I have sworn faithfully to perform the duties of the office of the Governor of this State, and with your aid they shall be faithfully performed. These constitutions and laws are meant for the guidance of official conduct and for your protection and welfare. The first I find recorded for my observation is that which declares it shall be the duty of the Governor to maintain and defend thesovereignty and jurisdiction of this State — and the most marked injunction of the Constitution to the Executive that he shall take care that the laws are faithfully executed.These Constitutions do not conflict; the line of separation between the responsibilities and obligations which each imposes is well defined. They do not embarrass us in the performance of our duties as citizens and officials.I shall not, on this occasion, dwell upon the condition of our country. The power and the position of our own State had been happily alluded to by my predecessor. My views upon this subject will be laid before you in a few days in my Message to the Legislature.This occasion, fellow-citizens, when official power is so courteously transferred from the hands of one political organization to those of another holding opposite sentiments upon public affairs, is not only a striking exemplification of the spirit of our institutions, but highly honorable to the minority party. Had our misguided fellow-citizens of the South acted as the minority of the citizens of our own State (a minority but little inferior in numbers to the majority) are now acting in this surrender of power the nation would not now be involved in Civil War.While fully aware that I shall have but little control of public affairs in the position to which I have been called and can not do much to shape events, I yet venture to trust that before the end of my term of service, the country will again be great, glorious and united as it once was; and in conclusion, I now offer to Almighty God my fervent prayer that the clouds which overhang us may be scattered, and that the close of my official term may find our people united in peace and fraternal affection, and the Union restored to what it was while we listened to the advice of our fathers.”40

This inaugural was brief but reflected Seymour’s persistent attempts to give conflicting messages to multiple audiences. His message a few days later to the Legislature was more expansive. Historian Sidney David Brummer noted that “little more than a quarter of the document was devoted to affairs relating to this State. The rest formed a complete manifesto for the Democratic party. If the Governor recognized that he could have but little direct influence on the policy pursued at Washington, he nevertheless thought his message a fitting vehicle to convey his ideas in full even upon subjects which did not directly touch New York. Of that part of the message dealing with the State, the most interesting passage, in view of subsequent events was that relating to the draft. The Governor stated that New York still owed almost 31,000 men to fill its quota, unless the national authorities would give the State credit for the excess sent before July, 1862. He urged that the Legislature give its ‘immediate attention to the inequality and injustice of the laws under which it is proposed to draft soldiers.”41 Among the points which Seymour made in setting himself up in opposition to federal military authorities:

- “We must accept the condition of affairs as they stand. At this moment the fortunes of our country are influenced by the results of battles. Our armies in the field must be supported; all constitutional demands of our General Government must be promptly responded to. But war alone will not save the Union. The rule of action which is used to put down an ordinary insurrection is not applicable to a wide-spread armed resistance of great communities. It is weakness and folly to shut our eyes to the truth.”42

- “While the War Department sets aside the authority of the Judiciary and overrides the laws of the States, the Governors of the States meet to shape the policy of the General Government, the National Legislature appoints committees to interfere with the military conduct of the war, and Senators combine to dictate the Executive choice of constitutional advisers. The natural results of meddling and intrigue have followed…the heroic valor of our soldiers and the skill of our generals are thwarted and paralyzed.”43

- “It is a high crime to abduct a citizen of this State. It is made my duty by the Constitution to see that the laws are enforced. I shall investigate every alleged violation of our statutes, and see that offenders are brought to justice. Sheriffs and district attorneys are admonished that it is their duty to take care that no person within their respective counties is imprisoned, or carried by force beyond their limits, without due process or legal authority.”44

- “I shall not inquire what rights States in rebellion have forfeited, but I deny that this rebellion can suspend a single right of the citizens of loyal States. I denounce the doctrine that civil war in the South takes away from the loyal North the benefits of one principle of civil liberty….”45

- “‘Martial law’ defines itself to be a law where war is. It limits is own jurisdiction by its very term. But this new and strange doctrine holds the loyal North lost their constitutional rights when the South rebelled, and all are now governed by a military dictation. Loyalty is thus less secure than rebellion, for it stands without means to resist outrages or to resent tyranny.”46

“The Tribune spoke of the message as exhibiting ‘the dexterous dishonesty, the impudent though adroit sophistry of the demagogue,'” wrote historian Brummer. “But Seymour was neither dishonest nor a demagogue, even though he may have been an adroit and dexterous politician. Though the manifesto seemed to portend a collision with the government at Washington and thus was encouraging to certain disloyal elements of the party, yet the fact that Seymour came out in favor of sustaining the prosecution of the war, even though he did not do it a very zealous manner, was creditable to him.”47Meanwhile, noted biographer Stewart Mitchell, Seymour had been a lightening rod for vicious criticism: “[Daniel S.] Dickinson and [Horace] Greeley persisted in calling Seymour a Copperhead, for it was easier to lump critics and traitors together than to try to do the right thing the right way. It is highly unlikely that either the orator or the editor looked for any evidence on which to convict Seymour of treason.”48

Seeking northern unity in prosecuting the war, President Lincoln reached out repeatedly to Governor Seymour. As chief executive of the Union’s most populous state, Seymour was in a position to assume the leadership of states’ rights. He could not be ignored. “Abraham Lincoln beheld the rise of Horatio Seymour will well-placed apprehension,” wrote historian William B. Hesseltine.49 On March 23, 1863,President Lincoln reached out to Seymour by letter:

You and I are substantially strangers; and I write this chiefly that we may become better acquainted. I, for the time being, am at the head of a nation which is in great peril; and you are at the head of the greatest State of that nation. As to maintaining the nation’s life, and integrity, I assume, and believe, there can not be a difference of purpose between you and me. If we should differ as to the means, it is important such difference should be as small as possible—that it should not be enhanced by unjust suspicions on one side or the other. In the performance of my duty, the co-operation of your State, as that of others, is needed—in fact, is indispensable. This alone is a sufficient reason why I should wish to be at a good understanding with you. Please write me at lest as long a letter as this—of course, saying in it, just what you think fit.50

Republican Chauncey M. Depew asserted: “Governor Seymour made no reply. He and the other Democratic leaders thought the president, uncouth, unlettered, and very weak. The phrase ‘please write me at least as long a letter as this’ produced an impression upon the scholarly, cultured, cautious, and diplomatic Seymour which was most unfavorable to its author. Seymour acknowledged the receipt of the letter and promised to make a reply, but never did.”51 As historian Sidney David Brummer observed, Seymour was essentially “not a bold enough man.”52 Actually on April 14, Governor Seymour actually did reply to President Lincoln:

I have delayed answering your letter for some days with a view of preparing a paper in which I wished to state clearly the aspect of public affairs from the stand point I occupy I do not claim any superior wisdom, but I am confident the opinion I hold are entertained by one half of the population of the Northern States I have been prevented from giving my views in the manner I intended by a pressure of official duties which at the present stage of the Legislative session of this State confines me to the Executive Chamber until each midnight…In the mean while I assure you that no political resentments, or no personal objects will turn me aside from the pathway I have marked out for myself — I intend to show to those charged with the administration of public affairs a due deference and respect and to yield them a just and generous support in all measures they may adopt within the scope of their constitutional powers. For the preservation of this Union I am ready to make every sacrifice of interest passion or prejudice….53

The Governor’s brother, John F. Seymour, became a key contact between the two leaders. John Seymour reported to his brother that he told Mr. Lincoln that “you had no aspirations forthe Presidency; that when you were here with me several years ago you said you did not envy the occupant of the White House; that there was too much trouble and responsibility, and no peace there; that you, and those who believed with you, were determined to sustain and maintain this Government and keep the country unbroken, and considered the ballot box the only remedy for evils; that you contended for respect for those in authority, and that while holding him responsible, you would sustain him against any unconstitutional attempts against his administration from any quarter; that these were the doctrines of your message. He said he would read it. I also said although you did not indulge in loud denunciation of the rebellion as that was not your manner, yet it was a very great grief to you; that you were especially vexed at some of the Republican party who claimed to have a patent right for all the patriotism.”54

At this point, Governor Seymour appeared to want to conciliate but not be coopted by President Lincoln. “Seymour believed that emancipation, conscription and the suspension of habeas corpus were completely unsound policies,” wrote biographer Stewart Mitchell.55 Historian William Hesseltine wrote: “In Horatio Seymour, it was evident, the forces of national concentration had met a foeman worthy of their steel. Lincoln, as usual, approached his antagonist cautiously. He listened respectfully when John Seymour appeared at the White House as his brother’s personal ambassador. The President explained with pointed patience that he had the same interest as the Governor in the life of the country. He pointed out that unless the Union were saved, there would be no next president of the United States. He pointed out that most of the officers in the army were Democrats — and he succeeded, in talking to Brother John, in keeping all discussion of Seymour’s policies on a partisan level. Not once did he admit that the New York Governor had other objectives than the Presidency. Brother John could only sputter that Brother Horatio had no ambitions to be president. Abraham Lincoln probably smiled understandingly.”56

Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote: “In the light of our knowledge of the private and personal means of communication between the governor and the President, much of the criticism of Seymour’s delay in acknowledging Lincoln’s letter of March 23 and of the tone of that acknowledgment is idle. The content of the letter he sent to Washington is concise, and the import of the words he used in that letter is clear. He has been accused of failed to send a second letter as he promised, but an examination of the text of what he wrote shows that he stated merely that he would ‘give’ the President his opinions and purposes with regard to the condition of ‘our unhappy country.’ There is no reason to suppose that he did not keep that promise by word of mouth.”57

“But out of that interview grew the technique for handling Seymour — the Governor was never to be regarded as more than an ambitious schemer for power,” wrote historian William B. Hesseltine. “Moreover, the very exigencies of the situation put Seymour at a disadvantage. His words — however scholarly — could not stand against Lincoln’s Union-saving sentiments or the radicals’ humanitarian gabble. Knowing this, Seymour sought to avoid letter-writing and conduct business with Washington through personal messengers. But therein again he played into Lincoln’s hands. The President was master of a literary style that Seymour, for all his oratory, could not match. And Lincoln, seeing that Seymour would not write, awaited an opportunity to put the Governor at a disadvantage.”58

“Against so charming and disarming an appeal the Governor had no weapons. Defeated before he started, Seymour could only send another messenger. But he wrote a note saying he would reply, and promising support for any constitutional acts of the administration. Lincoln ignored the fact that Brother John again appeared to talk of arbitrary arrests. This was no letter as long as his, and, having waited a reasonable time, he gave his own letter to the press. In the situation, Seymour, champion of states’ rights, was definitely worsted,” wrote historian Hesseltine.59

Colonel Silas W. Burt, a military aide to Governor Seymour, wrote that he delivered a dispatch from Seymour to the President at the Soldiers’ Home on May 26, 1863:

After the servant returned and announced that the President would receive us, we sat for some time in painful silence. At length we heard slow, shuffling steps come down the carpeted stairs, and the President entered the room as we respectfully rose from our seats. That pathetic figure has ever remained indelible in my memory. His tall form was bowed, his hair disheveled; he wore no necktie or collar, and his large feet were partly incased in very loose, heel-less slippers. It was very evident that he had got up from his bed or had been very nearly ready to get into it when were announced, and had hastily put on some clothing and those slippers that made the flip-flap sounds on the stairs.It was the face that, in every line, told the story of anxiety and weariness. The drooping eyelids, looking almost swollen; the dark bags beneath the eyes; the deep marks about the large and expressive mouth; the flaccid muscles of the jaws, were all so majestically pitiful that I could almost have fallen on my knees and begged pardon for my part in the cruel presumption and impudence that had thus invaded his repose. As we were severally introduced, the President shook hands with us, and then took his seat on a haircloth-covered sofa beside the Major, while we others sat on chairs in front of him. Colonel Van Buren, in fitting words, conveyed the message from Governor Seymour…..60

Governor Seymour and President Lincoln had come into conflict in mid-May when Seymour criticized handling by General Ambrose Burnside of the arrest of former Congressman Clement Vallindigham — which has led to orders from President Lincoln of his expulsion through Union lines into the Confederacy. “I do not hesitate to denounce the whole transaction as cowardly, brutal, and infamous. Unless the case shall assume some new aspect, I shall take an early public occasion to express my views upon the subject.”61 Seymour sent a message to the Democratic mass meeting that was called in Albany to protest the Vallandigham case. In a letter read at the rally, Seymour said: “I cannot attend the meeting at the capitol this evening, but I wish to state my opinion in regard to the arrest of Mr. Vallandigham. It is an act which has brought dishonor upon our country. It is full of danger to our persons and our homes. It bears upon its front a conscious violation of law and justice.”62 The meeting produced a series of resolutions which were transmitted to President Lincoln by Congressman Erastus Corning. Mr. Lincoln’s reply is considered one of his most distinguished state papers.

Seymour was clearly positioning himself as a leader of anti-Administration Democrats. Historian Mark E. Neely, Jr., wrote: “Governor Horatio Seymour …tailored his state messages and pronouncements to a national audience. Like many other democrats, Seymour thought conscription unconstitutional, and he expected the courts soon to declare it so. Indeed, Chief Justice Taney had already written a decision declaring the draft unconstitutional and had it sitting in his desk drawer awaiting a case to come before the court. Democratic workingmen in New York expected their governor and party to protect them from the draft. When the draft commenced as scheduled, a protest against it soon degenerated into wild racial and partisan rage against the Republicans and against innocent blacks, assumed to be favored beneficiaries of Republican policies; victims were sometimes beaten beyond physical recognition by the furious mob.”63

Historian James G. Randall contended that Seymour “was all in all a loyal Democrat. He believed, however, that the South had rights, distrusted an abolitionist war, was vexed at the Republican party’s claim to a ‘patent right for all the patriotism,’ favored adherence to constitutional methods, considered conscription unconstitutional as well as unnecessary, and felt confident that recruitment, which he actively promoted in New York, would accomplish the purpose. He was not the politician type. The people of New York had elected him knowing his views, thereby rejecting Wadsworth who upheld Lincoln, and he felt that acquiescence in certain of the doubtful measures of the administration would be a kind of desertion from his party’s and his people’s standard. His opposition to Lincoln was genuine; it was not that of the demagogue; yet in the controversy between them Lincoln came through with the better showing. Perhaps it should be added that the nature of the contest gave Lincoln the advantage. To oppose conscription in time of gigantic and desperate war, and to do it with an unavoidable suspicion of party motive, is no easy task. When Lincoln wrote a frank and conciliatory letter asking cooperation, the governor sent a cold and guarded reply, but it cannot be said that he showed actual non-cooperation with the Washington government in the more vital mattes. Lincoln’s approach was to treat the situation as if no difference or controversy existed, or at least to relegate disputes to the background. He addressed the governor with respect, spoke generously in conference with the governor’s brother, showed readiness for reasonable adjustment, and in the outcome was successful in upholding the draft law.”64

Biographer Stewart Mitchell also defended Seymour: “For two years, and in the very midst of civil war, Governor Seymour tried to maintain the integrity of the Constitution according to his honest understanding of it. This effort brought him into collision with the hasty and arrogant men in the service of Abraham Lincoln. The points of policy in dispute, moreover, were emancipation, conscription, and arbitrary arrest. There is no good reason for believing that either leader was not sincere.”65

Presidential aide John Nicolay had a much less favorable view of Seymour’s actions. “Among a considerable number of individual violations of the [conscription] act, in which prompt punishment prevented a repetition, only two prominent incidents arose which had what may be called a national significance. In the State of New York the partial political reaction of 1862 had caused the election of Horatio Seymour, a Democrat, as governor. A man of high character and great ability, he, nevertheless, permitted his partizan feeling to warp and color his executive functions to a dangerous extent. The spirit of his antagonism shown in a phrase of his fourth-of-July oration: ‘The Democratic organization look upon this administration as hostile to their rights and liberties: they look upon their opponents as men who would do them wrong in regard to their most sacred franchises,” wrote presidential aide John G. Nicolay in his biography of President Lincoln.66 Nicolay viewed Seymour’s actions during the four-day draft riots in July 1863 even less favorably: “Governor Seymour gave but little help in the disorder, and left a stain on the record of his courage by addressing a portion of the mob as ‘my friends.'”67

Seymour committed several errors that hurt him politically. By beginning his speech with the words “My friends,” recalled Republican politician Chauncey M. Depew, “The governor’s object was to quiet the mob and send them to their homes. So instead of saying ‘fellow citizens’ he used the fatal words ‘my friends.’ No two words were ever used against a public man with fatal effect. Every newspaper opposed to the governor and every orator would describe the horrors, murders, and destruction of property by the mob and then say: ‘These are the people whom Governor Seymour in his speech from the steps of the City Hall address as ‘my friends.'”68 It was a mistake that Republican partisans never let Seymour forget. In one speech in nearly City Hall Park in the fall campaign, Unionist Lyman Tremaine declaimed: “Here was a scene for the painter! The Governor of this powerful State standing before a mob whose hands were red with the blood of their murdered victims, alarmed at the storm which had been raised, promising to do what he could to give them the victory over law — sanctioning by implication the miserable notion that the law discriminated between the rich and the poor, and pledging himself to raise money to relieve them from the effects of the law!”69

Historian David Sidney Brummer observed that “if these words of salutation did not make Seymour the traitorous governor that some of the newspapers described, his sympathetic attitude toward the alleged grievances of the rioters deserves condemnation. It appears very probable that the Governor’s mildness did little good. His course was perfectly consistent with his character; by no means disloyal, but showing gentleness where vigor and determination were requisite; censuring unlawful deeds, but haggling over constitutional rights at a most inopportune time.”70

Seymour continued to fight conscription in principle and practice — in a series of letters exchanged between himself and President Lincoln in early August 1863. On August 7, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary: “The President read to us a letter received from Horatio Seymour, Governor of New York, on the subject of the draft, which he asks may be postponed. The letter is a party, political document, filled with perverted statements, and apologizing for, and diverting attention from, his mob. The President also read his reply, which is manly, vigorous, and decisive. He did not permit himself to be drawn away on frivolous and remote issues, which was obviously the intent of Seymour.71

Seymour’s opposition to conscription carried over to another area of military recruitment in 1863. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “All the more discreditable was the conduct of Northerners who, like Horatio Seymour, continued to oppose any military use of colored men. The full story of Seymour’s obstructiveness is full of drama. New York was one of the two Northern States which could send a really strong contingent of its own free Negroes to the front. As fighting ended at Chancellorsville a meeting was held in the metropolis to take measures for enlisting large numbers of colored volunteers, and a deputation immediately afterward waited on Lincoln, who told them that the national government could not support the undertaking until it was assured of the governor’s cooperation. Memorials were thereupon laid before Seymour, who ignored them. A pertinacious citizen of Albany, asking that a well-known colonel be empowered to raise one colored regiment, finally got a curt reply: ‘I do not deem it advisable to give such authorization, and I have therefore declined to do it.’ Prominent citizens of New York rallied to the battle. Peter Cooper, Henry J. Raymond, William E. Dodge, and others formed an association, and applied themselves anew to Lincoln and Stanton. The newly formed Union League Club joined the fray. Still Governor Seymour, making fresh excuses, was a lion in the path. If he could help it, New York would never arm a Negro.”72

Historian James G. Randall wrote: “In the pages of Nicolay and Hay, the governor is made to appear in a very bad light. By their account, he denounced enrollment, demanded that Federal authorities submit to state control, asked to have the draft suspended, showed sympathy for the rioters, accused draft officials of frauds, directed ‘insulting charges against Lincoln, and showed himself a partisan in his hostility to the execution of the law. He and his friends, say Nicolay and Hay, made the proceedings of the government ‘the object of special and vehement attack.'”73 Historian Randall observed: “With all the immense and many-sided burdens of 1863, the President treated Seymour with great respect, patiently answered his complaints, and sought continually for a working adjustment of conflicting views. During these months of controversy the nation was going through severe ordeals as it watched the military news while also, in the states, the political pot was boiling in state elections spread out over a tiresome period from spring until late fall.”74

In his first year in office, Seymour had created a variety of reason to oppose his reelection. Biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote, “By the autumn of 1863 Seymour had been governor for less than a year but he had raised up enemies on every side. His pressure for recruiting disappointed the comparatively small Copperhead element in the state; his opposition to the draft and its enforcement led many men to class him with the lukewarm friends of the Union. He had blocked, with his veto, the bill giving votes to soldiers, insisting that the constitution of the state must be amended for that express purpose. He forced the legislature to pay foreign creditors of New York in gold, and easy-money men denounced him as a tool of the bankers. Bennett, of the powerfulHerald, had failed to plant a friend on the metropolitan board of police; Greeley, of the Tribune, accused him of conspiracy in the riots of July. Tammany had lost a valuable traction franchise by his veto….The drafts of August and October proved that the governor’s opposition to the hated policy of conscription was ineffective, and Stanton’s special commission would not vindicate Seymour’s claim for a correction of the figures until long after election day.”75

“In New York, though it was not a national election, nor for governor, the 1863 contest had unmistakable national significance,” wrote historian James G. Randall. “In the large it was a question of supporting either the administration of Lincoln or that of Seymour. The people were to vote for state officials other than governor — such as secretary of state, comptroller, and attorney general — but the declarations of the two parties spoke the language of Federal affairs. The Democrats favored united support of the national government for suppressing the rebellion and restoring the Union. They declared secession a false of doctrine. At the same time they denounced conscription, favored conciliation, objected to infringement of state rights, assailed what were called illegal and unconstitutional arrests, and expressed highest approval of the administration of Governor Seymour.”76

The resolution of the draft quota conflict somewhat sustained Seymour’s position, according to historian Sidney David Brummer: “By the subsequent adjudication of a commission appointed by the President, New York State was credited with more than thirteen thousand men. For this, Seymour received the unanimous thanks of the Assembly of 1864, a majority of whom were politically opposed to him. He certainly saved the State and also the local districts a large sum which otherwise would have been spent in bounties. But it should be noted that two of the three members of the commission were Democrats, one being William F. Allen, his party’s nominee for judge of the Court of Appeals in this very year and for lieutenant-governor in 1860, and an intimate friend of Seymour. Moreover, in arriving at the decision, the terms of the law, as to the adjustment of quotas were absolutely ignored.”77 The conflict with the Administration hardened Seymour’s opposition to the draft. Attorney George Templeton Strong wrote in early January 1864, “Governor Seymour’s message is understood to be a most copper-heady manifesto. Very likely. He seems strangely blind to the signs of the times. I supposed him sagacious and politic, though utterly base and selfish and incapable of any patriotic national impulse. But the manifestations of his malignity are those of a boor and not of a subtle politician.”78

“Seymour saw the approach of the presidential election of 1864 with almost as much anxiety as did Lincoln,” wrote biographer Stewart Mitchell. “The schemes of these Republicans to replace Lincoln at the head of affairs were as unwelcome to the governor as to the President himself. Nevertheless, when Seymour urged his party to put up a civilian, and a conservative civilian, his enemies accused him of talking for himself.”79

August Belmont observed in early August that Seymour “blows hot & cold…professes not to be a candidate & will be none if I can help it.”80 What Seymour did not want, according to biographer Stewart Mitchell was for George B. McClellan to be nominated for President — instead “urging the choice of a civilian on the national convention over which he presided at Chicago. He seems never quite to have trusted the military mind: Jefferson was more to his liking than Jackson.”81 Mitchell wrote: “Seymour faced a dilemma. His interest in blocking the policy of one man and heading off the nomination of the other drew attention to the difficult position of his party in 1864. It put up a man who complained that he had not been allowed to conduct the war properly on the platform of another man who believed that the war should end at once. McClellan, in the eyes of Seymour, had been guilty of arbitrary acts in Maryland in 1862; Vallandigham was a visionary.”82

At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in late August, Seymour played a prominent role. He declined, however, to be considered as a candidate for President — despite the support Mozart Hall’s Fernando Wood. “Horatio Seymour was proposed by the Committee on Permanent Organization as the convention’s permanent chairman. It was an expected tribute. As the New York State delegation traveled West, Seymour had met with continuous ovations, especially in Detroit, where ‘crowds, cheers, speeches and salvos of fire-arms greeted him.’ The convention action was but another attestation of this general party esteem,” wrote historian George Fort Milton. “The Governor of New York was given an ovation as he went to the chair. This was his opportunity. Such was the storm of cheers and the wild huzzas that if he had given the word, he could have been the nominee — and, what was more important, he could have written the platform and save the party from one of the blackest markets ever put upon its record. But he took no step, sent no word, gave no sign of willingness.”83

August Belmont had other ideas. He wanted to nominate General George B. McClellan for President and have Seymour run again for Governor. In truth, Seymour wanted to run for neither office. August Belmont biographer Irving Katz wrote: “Belmont was instrumental in persuading an unwilling Governor Seymour to become a candidate for reelection. His convincing argument, seconded by Marble, [Samuel] Tilden, and [Dean] Richmond, centered on Seymour’s earlier opposition to McClellan’s candidacy. The fact of this opposition, coupled with the governor’s refusal to run, could be regarded by voters as evidence that Seymour had no confidence in the general’s ability to carry the country in November. Seymour yielded to party pressure.”84

Aided by President Lincoln, Republican Congressmen Reuben E. Fenton of Chautauqua County defeated Seymour by a narrow margin of about 7,000 votes. Biographer Stewart Mitchell contended: “In spite of the common belief that Seymour was defeated for governor in 1864 because of what was supposed to be his attitude toward Lincoln and the Civil War, it is probably that his failure to secure a third term was owing chiefly, if not wholly, to his having alienated powerful support within his party by certain acts connected with state policy.”85 Mitchell cited as contributing causes the intra-party feuding over the New York City police board and railroad franchises in the city.

Footnotes

- Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, p. 166-167.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 302-303.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 268.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 297.

- William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South, p. 9-10.

- William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South, p. 9.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 154 (September 27, 1862).

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 14.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 445.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Midstream, p. 292.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Midstream, p. 292-293.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 224.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 225.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 117.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 118.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 231.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 228.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 229.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 239.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 240.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 249.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 217-218.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 302.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 303.

- George Fort Milton, Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column, p. 119.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 248.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 235.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 317.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 283-284.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 23.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 256.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 257.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 259.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 428.

- Don E. And Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 464 (from Albany Atlas and Argus, April 16, 1864).

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VII, p. 12-13.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 282.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 255-256.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 262-263.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 264-265.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 258.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 268.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 259.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 260.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 271.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 271.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 261.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 298.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 282.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 145-46 (Letter to Horatio Seymour, March 23, 1863).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 27-28.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 263.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Horatio Seymour to Abraham Lincoln, April 14, 1863).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 276.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 278.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 285.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 277.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 286.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 286.

- Rufus Rockwell Wilson, editor, Lincoln Among His Friends, p. 331-333.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 293.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 293.

- Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Last Best Hope on Earth, p. 127-128.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume II, p. 295-296.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 295.

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, p. 356.

- John Hay and John G. Nicolay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, p. 357.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 29.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 347.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 322.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 395 (August 7, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 525.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume II, (295).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Midstream, p. 293.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 351.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Midstream, p. 278.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 330-331.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 390 (January 5, 1864).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 337.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 372.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 260.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 362.

- George Fort Milton, Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column, p. 223.

- Irving Katz, August Belmont: A Political Biography, p. 118.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 283.