“The mayor of the city, George Opdyke, and Governor Horatio Seymour begged for help in every direction. Governor Seymour even sought help from Archbishop Hughes,” wrote historian Frank Klement.1 The unusual political alliance of Geo. Opdyke, Wm C. Bryant, Horace Greeley, Henry J. Raymond wrote President Lincoln: “We beg to urge upon you the adoption of the policy recommended in Mr Field’s letter of Sunday forwarded by Mr. Blake. That will indicate the authority and prestige of the Government while it will greatly lessen, if not entirely abate the opposition to the conscription”.2 “At noon Tuesday, Mayor Opdyke finally asked Secretary of War Stanton to send New York City what military force he could spare.”3

Several prominent New Yorkers including George Templeton Strong telegraphed the President: “Our City having given her Militia at your call is at the mercy of a mob which assembled this morning to resist the Draft & are now spreading fire & outrage— Several buildings in different wards are in flames & the “Times” & “Tribune” offices are at this moment threatened[.] New York looks to you for instant help in troops & an officer to Command them and to declare martial law[.] Telegraph wires cut in all directions[.]”4

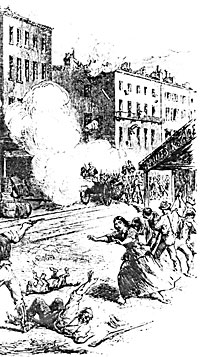

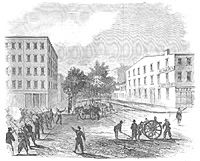

“The secretary of War ordered all the New York regiments to repair to New York, and on the evening of the 15th the Tenth and Fifty-sixth had arrived. Soon after came the Seventh, Eighth, Seventy-fourth and One Hundred and Sixty-second, and the Twenty-sixth Michigan. They had come none too soon, for destruction raged up to the moment of their arrival,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt.5 “Not until the Seventh New York Regiment arrived, early on Thursday morning, did the violence subside. Before the day was over, three more regiments brought the total number of troops in the city to 4,000. After a bloody confrontation between soldiers and rioters near Gramercy Park on the evening of July 16, the uprising collapsed,” wrote William K. Klingaman.6

President Lincoln’s friend, journalist Noah Brooks, wrote: “At first the President proposed to send General [Judson] Kilpatrick, a dashing cavalry officer, to the scene of the riot, thinking that his name would be a terror to the lawless gangs that had ravaged the city. Horatio Seymour, Governor of the State, harangued the mob in dulcet tones, addressing them as ‘My friends,’ and urging them to disperse. But sterner measures were soon required; troops were recalled from Pennsylvania, and after a demonstration of military force the riot was suppressed and order restored.”7 According to William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets, after the crowd gathered in front a City Hall in downtown Manhattan, “The Governor came out and stood at the top of the steps. Tweed was standing by his side….He is fat and pompous. But he is not afraid. Governor Seymour is afraid. You can tell by the whiteness of his face. And his hands shake. Tweed’s hands are steady. Sheep, all of them.”8

Historian William Hesseltine wrote: “In the city Seymour consulted Mayor Opdyke and issued a proclamation ordering the rioters to disperse. At the city hall he addressed the mob. ‘My friends,’ he began as he pleaded with them to cease destroying property. Republicans pounced with glee on the phrase, which proved Seymour’s affiliation with the rioters. But the rioters, friend or no, failed to disperse. Later in the day the Governor issued a second and more stringent order — and by that time troops had arrived and the mob dissolved.”9 Biographer Stewart Mitchell defended Seymour use of the introductory “My friends” by writing that “bloody-thirsty rioters, roaming through a city on a second day of evil deeds, are hardly likely to stop and listen to a speech.”10 Seymour was much criticized in following weeks and years for this phrase but Mitchell noted that he “always laughingly denied that he had called ‘rioters’ his ‘friends,’ because he could not remember that he had ever seen one.”11 Seymour told New Yorkers: “I come, not only for the purpose of maintaining law, but also from a kind regard for the interest and welfare of those who, under the influence of excitement and a feeling of supposed wrong, were in danger not only of inflicting serious blows to the good order of society, but to their own interests. I beg of you to listen to me as your friend and the friend of your families.”12

Sandburg wrote: “The draft…and the arrangement that any man have $300 could buy his release from military service, were the focal points of the mass drive of the mobs. Robert Nugent, assistant provost marshal in charge of conscription, received on the second day of the riots a telegram from his Washington chief, James B. Fry, directing him to suspend the draft. Governor Seymour and Mayor Opdyke clamored that he should publish this order. Nugent said he had no authority to, but he finally consented to sign his name to a notice: ‘The draft has been suspended in New York City and Brooklyn,’ which was published in newspapers. This had a marked quieting effect.”13

The Catholic Church was called on to restrain its Irish-American flock in the crisis. Historian Frank Klement wrote: “Some Catholic priests went into the streets to restrain the rioters, often their own parishioners. One talked some looters into returning their plunder. One prevented the burning of a block of houses inhabited by Protestants. Another prevented an attack upon buildings making up Columbia College (now Columbia University). Still another succeeded in dispersing a mob in his neighborhood. But generally, neither the pleas of the priests nor the proclamations of the authorities could stay the whirlwind of destruction and death.”14

Historian Paula Baker wrote: “If the riot revealed massive conflicts among New Yorkers, so did efforts to deal with its consequences. Some of the early rioters, including the firemen, joined efforts to restore order as soon as Monday evening. Working-class Germans, too, participated in block watches to protect property. Divisions among elite New Yorkers also reemerged. Some Union League members hoped to see martial law declared, the rioters punished severely, and the city brought under military control — with luck under Benjamin Butler, a New England abolitionist and general famous for his ironfisted control of Union-occupied New Orleans. In the meantime Union Leaguers became the core of the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People Suffering from the Late Riot, which made a substantial amount of money available to African Americans to rebuild their lives in the city.”15

One historian wrote: “Archbishop Hughes, thus, had a hand in bringing the four-day antidraft riot to an end. There were other factors, of course. Troops had arrived in force and helped authorities to arrest many. Reasonable community leaders made their influence felt. Word that the draft had been suspended and postponed served as a sedative. The fires of resentment in the hearts of the rioters simply burned themselves out. The costs were high: 119 known dead, about 400 wounded or injured, and property damage approximating three million.”16 Historian Iver Bernstein wrote that “in the Hughes` episode, republican authorities had begun to act with some circumspection in their relations with conservative leaders. The conciliatory style was confirmed as the dominant mode of social relations in the city.”17

“The riots were brought to an end on the evening of Thursday, July 16, and the city immediately resumed its customary aspect, while the authorities proceeded to calculate the amount of damage that had been sustained. The exact number of rioters killed was never ascertained,” wrote Major T. P. McElrath.18 General John E. Wool, commander of the Eastern District, telegraphed General Henry W. Halleck on Friday morning, July 17: “I think we shall put down the riot in this city in the course of this day. We had a brush with them last night, and they were dispersed. In searching their houses, we found 70 carbines, revolvers, &c., and barrels of paving stones. The numbers of the rioters are very great, but scattered about in different parts of the city, where they plunder houses whenever the opportunity offers, in the absence of troops. The several regiments which arrived yesterday afternoon and evening will, I trust, enable us to crush all these parties in the course of this day. The gallant and distinguished Brigadier General [Judson] Kilpatrick reported himself to me this morning for service for a few days. I have placed him in command of the few cavalry I have.

Major McElrath wrote: “On July 17th, an unexpected order was received from the War Department relieving General Brown from the command of the city and harbor of New York, General [Edward R.] Canby being sent from Washington to assume the position. On the following day, General Wool was superseded by Major General John A. Dix. Old age and consequent infirmity rendered the removal of General Wool from so responsible a command a matter of perfect propriety, but the citizens of New York, conscious of the debt of gratitude they owed to General Brown, were very reluctant to see him so peremptorily supplanted at the very moment of his and their triumph. The orders in both cases were dated the 15th, and, doubtless had their origin in a supposition at the War Office that so extensive an outbreak must, in some degree, be attributed to the inefficiency of the commanding officers. To a certain extent such an impression was correct. The strong contrast presented throughout the riots by the conduct of the three generals between whom the command was nominally divided enabled observers, even during the height of the excitement, to recognize the difference between capacity and titled incompetency. General Wool, in his temporary office at the St. Nicholas Hotel, unconscious of the real condition of things, and issuing orders contrary to reason and to military precedent, and General [Charles W.] Sanford in citizens’ dress, jealously locking himself up for three days in the arsenal, collecting about him eagerly every soldier he could lay his hands upon, and in no single instance initiating a movement against the rioters of sufficient consequence to receive mention in the daily journals, were types of prejudiced inefficiency; while General Brown, on duty without intermission through four days and nights, covering the entire city of New York with a military force whose aggregate number was smaller than the bodies of rioters which any one of its detachments came into collision, co-operating generously with the sturdy Police Commissioners, and bending his whole energies to the single task of carrying out their plans for saving the city, was emphatically the man for the occasion.”19

Navy Secretary Welles wrote as early as July 15: “General Wool, unfitted by age for such duties, though patriotic and well-disposed, has been continued in command there at a time when a younger and more vigorous mind was required. In many respects General Butler would at this time have best filled that position….[Salmon P.] Chase tells me there will probably be a change and that General Dix will succeed General Wool. The selection is not a good one, but the influences that bring it about are evident. [Secretary of State William H.] Seward and [Secretary of War Edwin M.] Stanton have arranged it.”20

Historian Philip S. Paludan wrote: “The attention of the nation was riveted on events in the city, on the vast homefront violence — it was the most murderous urban riot in the nation’s history. And it raised a vitally important question: how dedicated was the administration to upholding the draft law, or the rule of law itself? The New York City Republican elite demanded a draconian response. Members of the Union League Club urged Lincoln to declare martial law and to send regiments to control the city — preferably headed by Ben ‘Beast’ Butler — and to hang or shoot not only rioters but conservative Democratic politicians and journalists.”21

Iver Bernstein wrote that “it was General Dix’s wartime reputation as a relentless opponent of treason as Commander of the Maryland Department that won him the job of preserving order in post-riot New York. President Lincoln was committed to enforcing the New York draft — this was the message that Samuel Barlow received from T.J. Barnett, his Hoosier informant inside the White House. Lincoln and Stanton knew that General Dix would carry out the draft in New York at all costs. They no doubt also realized that Dix commanded the respect of metropolitan elites of all political stripes and would succeed, if anyone could, in mobilizing conservatives behind conscription and the post-emancipation war effort.”22 He was able to get the cooperation of Tammany Democrats for the August drafts.

But unless the Lincoln Administration got cooperation for conscription in New York City, cooperation in other areas of the country would be threatened. “Across the North, political and business leaders anxiously awaited Washington’s full response to the New York upheaval,” wrote historian Bernstein. “Provost marshals in Des Moines wired the president on Wednesday the 15th, ‘Suspension of the draft in New York as suggested by Gov. Seymour will result disastrously in Iowa. A Wilkes-Barre Republican warned Secretary Seward, ‘Depend on it, sir, the draft cannot be enforced in this county if the Administration compromises with the rebels in New York. The loyal men here will not sustain the draft unless it is enforced in New York.'”23

President Lincoln was careful not to overreact to the riots. “Lincoln and other federal officials rejected a ham-fisted solution to the insurrection in New York City,” wrote Iverson. “While Republican governments imposed military rule on other draft riot districts, various Southern-sympathizing cities, and whole regions of the South during the sixties, martial law was never declared in New York. Nor did New Yorkers witness the impromptu sentencing and execution of draft rioters by military street tribunals and firing squads.”24 Presidential aide William O. Stoddard wrote: “Mr. Lincoln was bitterly but unjustly blamed for the occurrence of the Draft Riot. Men saw that its apparent cause and opportunity came from his action as Chief Magistrate of the nation, and many did not look much further. They failed to consider that he was as ignorant as they were that the wild beasts of Europe were so numerous in the dens of New York City.”25

“The New York draft riot had featured such horrible antiblack brutality that racist appeals were sullied by association. Backlash against the mutilations, burnings, and murders eroded the power of Democratic hatemongering,” wrote historian Philip S. Paludan.26 The riots also provided an excuse for anti-Irish, anti-Catholic prejudice. “More than any other group, the patrician elite viewed the draft riots as a pure Irish Catholic uprising. In his epitaph to the insurrection, Strong wrote, ‘For myself, personally, I would like to see war made on the Irish scum as in 1688.'”27

But Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell downplayed the magnitude of the riots. “In view of what actually happened on July 13 and 14, 1863, the magnifying of the reports may be thought mysterious. More than one person, however, had good reasons for exaggerating the extent and damage of these riots. The people for whom Horace Greeley was spokesman hoped that if Lincoln were only sufficiently alarmed, he would proclaim martial law, and then the city could be governed with ease. Troops were sent into New York to insure safety at the resumption of the draft in August. Governor Seymour and his friends, on the other hand, had no desire to minimize popular discontent with the quotas assigned to the six congressional districts of New York and Brooklyn. Lincoln, it was believed, might be persuaded to revise the demands — as, indeed, he did when confronted with the figures which Seymour submitted to him. The governor made another point, moreover; all the violence and disorder of the week had been put down by the metropolitan police with very little aid from the military. New York, it was implied, both city and state, was quite able to manage its own affairs. A third group of persons, if not most numerous, was most important in swelling the total of the casualties and damages. A very large group of citizens were not long in awaking to the fact that they could make money by making the most of the riots.”28

Footnotes

- Frank Klement, Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads of the North, p. 104.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 54.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 418.

- William K. Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865, p. 264.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from George Opdyke et al. to Abraham Lincoln, July 21, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from J. Jay, G. T. Strong, W. Gibbs, and J. Wadsworth to A. Lincoln, July 13, 1863).

- Noah Brooks, Abraham Lincoln: The Nation’s Leader in the Great Struggle Through Which was Maintained the Existence of the United States, p. 375.

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 136-137.

- William Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 299.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 324.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 327.

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 137.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume III, p. 362.

- Frank Klement, The Copperheads of the North, Lincoln’s Critics, p. 104.

- Milton M. Klein, editor, The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 436 (Paula Baker, “New York during the Civil War and Reconstruction”).

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 62-63.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 62-63.

- Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South, Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, p. 302 (T.P. McElrath, “The Draft Riots in New York”).

- Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South, Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, p. 302-303 (T.P. McElrath, “The Draft Riots in New York”).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 373 (July 15, 1863).

- Philip S. Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 213.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 62-63.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 59.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 60.

- William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln: The Man and the War President, p. 400.

- Philip S. Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 289.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 157.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 332.