Aerial View of New York 1867

View of Baxter (late Orange St.) betw. Hester & Grand St. 1861

Park Place

Ladies Union Aid Society, West 42 St East of 8th Ave.

New York City and environs, from the spire of Dr. Spring’s new brick church

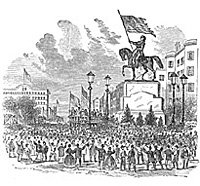

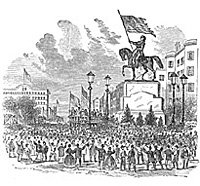

Union Square, New York, on April 20, 1861

West Point and the Highlands

Broadway at Exchange Place

While alive, Mr. Lincoln visited New York on six occasions. None of these visits was lengthy. The longest, in February 1860 lasted only three nights. On two of these visits — in September 1848 and June 1862, Mr. Lincoln merely lasted through the city on the way north. The June 1862 was the only visit Mr. Lincoln made to the city as President. He made another one as in February 1861 when the President-elect was received in a correct but cool manner by skeptical New Yorkers.

On his second visit to the city in July 1857 when he was see, there is virtually no record. In fact, the only known comment about the trip comes in a letter written by his wife, who was clearly captivated by New York City. Mrs. Lincoln returned once again on a shopping trip in December 1860 and on many subsequent shopping trips as the country’s First Lady. For Mrs. Lincoln, New York was a city of opportunity and power. For Mr. Lincoln, however, it was a city of power and opportunists.

Although President Lincoln seldom left Washington during the Civil War except to visit the war front, New York City was never far away — either in thoughts or visitors. Receiving visiting delegations was an occupational hazard of being President. For Mr. Lincoln, the hazards began even before he took the oath of office. According to Lucius E. Chittenden, a Vermonter who later became an official of the Treasury Department, there was a memorable exchange between President-elect Lincoln and New York representatives to the Peace Conference at the Willard Hotel.

It was reserved for the delegation from New York to call out from Mr. Lincoln his first expression touching the great controversy of the hour. He exchanged remarks with ex-Governor [John A.] King, Judge [Amaziah B.] James, William Curtis Noyes, and Francis Granger. William E. Dodge had stood, awaiting his turn. As soon as his opportunity came, he raised his voice enough to be heard by all present, and, addressing Mr. Lincoln, declared that the whole country in great anxiety was awaiting his inaugural address, and then added: ‘It is for you, sir, to say whether the whole nation shall be plunged into bankruptcy; whether the grass shall grow in the streets of our commercial cities.’

“Then I say it shall not,” he answered, with a merry twinkle of his eye. “If it depends upon me, the grass will not grow anywhere except in the fields and the meadows.”

“Then you will yield to the just demands of the South. You will leave her to control her own institutions. You will admit slave states into the Union on the same conditions as free states. You will not go to war on account of slavery!”

A sad but stern expression over Mr. Lincoln’s face. ‘I do not know that I understand your meaning, Mr. Dodge,” he said, without raising his voice, ‘Nor do I know what my acts or my opinions may be in the future, beyond this. If I shall ever come to the great office of President of the United States, I shall take an oath. I shall swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, of all the United States, and that I will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. This is a great and solemn duty. With the support of the people and the assistance of the Almighty I shall undertake to perform it. I have full faith that I shall perform it. It is not the Constitution as I would like to have it, but as it is, that is to be defended. The Constitution will not be preserved and defended until it is enforced and obeyed in every part of every one of the United States. It must be so respected, obeyed, enforced, and defended, let the grass grow where it may.

Not a word or a whisper broke the silence…Mr. Dodge attempted no reply…Some of the more ardent Southerners silently left the room….For the more conservative Southern delegates, the statesmen, Mr. Lincoln seemed to offer an attraction. They remained until he finally retired.1

Businessmen, politicians, clergy, and journalists all visited Washington to share their ideas for winning or ending the war. Artist Francis B. Carpenter wrote: “Among the numerous delegations which thronged Washington in the early part of the war was one from New York, which urged very strenuously the sending of a fleet to the southern cities, — Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah, — with the object of drawing off the rebel army from Washington. Mr. Lincoln said the project reminded him of the case of a girl in New Salem, who was greatly troubled with a ‘singing’ in her head. Various remedies were suggested by the neighbors, but nothing tried afford any relief. At last a man came along, — ‘a common-sense sort of man,’ said he, inclining his head towards the gentleman complimentarily, — ‘who was asked to prescribed for the difficulty. After due inquiry and examination, he said the cure was very simple. ‘What is it?’ was the anxious question. ‘Make a plaster of psalm-tunes, and apply to her feet, and draw the ‘singing’ down,’ was the rejoinder.”2

Carpenter wrote that a New York delegation visited the President to press for Emancipation. “During the interview the ‘chairman,’ the Rev. Dr. C — , made a characteristic and powerful appeal, largely made up of quotations from the Old Testament Scriptures. Mr. Lincoln received the ‘bombardment’ in silence. As the speaker concluded, he continued for a moment in thought, and then, drawing a long breath, responded: ‘Well, gentlemen, it is not often one is favored with a delegation direct from the Almighty!'”3

Lincoln biographer Alonzo Rothschild wrote: “Early in September, 1862, a committee of prominent New Yorkers, led by the venerable son of Alexander Hamilton, called upon Mr. Lincoln ostensibly to urge ‘a change of policy.’ They represented, according to their own statement, not only the views of the dissatisfied Republican element in the Empire State, but of five New England Governors as well, The animus of their criticisms soon became apparent to the President, who, in the midst of the heated discussion that ensued, angrily exclaimed: ‘You, gentlemen, to hang Mr. Seward, would destroy the government.'”4 According to historian Glyndon Van Deusen, James A. “Hamilton renewed the attack on Seward the following morning, but with as little effect, and the baffled committee made its way back to New York.”5 It was one of several delegations who visited Mr. Lincoln that summer — many to press their ideas on military and emancipation policy. Though he had already written his draft Emancipation Proclamation, Mr. Lincoln refused to reveal his policy prematurely.

Not all visits with New Yorkers were so serious. After Fort Sumter had been attacked in April 1861 and New York troops arrived in the Capital to help protect it from Confederate forces, presidential aide John G. Nicolay wrote in his diary: “We (I mean the President and four of five others of us from the White House) spent a very agreeable afternoon from about 3 to 6 o’clock P.M. yesterday. The 71st Regiment New York Volunteers are quartered at the Navy Yard, and having several good musicians in the ranks, and a fine regimental band, by way of pastime improved a regular concert…in one of the large storerooms in the Navy Yard, which they occupy as barracks. They had an elegant audience of some two or three hundred invited guests, and make the enterprise a great success.” He added that they later “saw the 71st Regiment on ‘dress parade,’ and then went home.”6

New York entertainers sometimes visited the White House. On one occasion in 1863, the Lincolns played host at the White House to newly-married General Tom Thumb and his wife Lavinia — both prominently associated with Barnum’s Circus. For President Lincoln, New York was a political circus from which he was not far removed.

Footnotes

- Lucius E. Chittenden, Recollections of President Lincoln and His Administration, p. 74-75.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 239.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 239.

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln: Master of Men: A Study in Character, p. 155.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 346.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 41-42 (May 10, 1861).