Rev. Beecher Auctioning Pinky for Her Freedom

Plymouth Church Schoolroom, Brooklyn, Welcoming Back Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, Nov 17, 1863

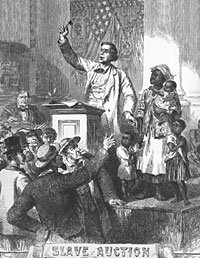

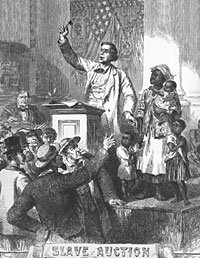

Mr. Beecher Selling a Beautiful Slave Girl in his Pulpit

Henry Ward Beecher was a fighter – and out of his Brooklyn pulpits. “One of the greatest and most remarkable orators of his time was Henry Ward Beecher. I never met his equal in readiness and versatility. His vitality was infectious. He was a big, healthy, vigorous man with the physique of an athlete, and his intellectual fire and vigor corresponded with his physical strength. There seemed to be no limit to his ideas, anecdotes, illustrations, and incidents. He had a fervid imagination and wonderful power of assimilation and reproduction and most observant of eyes. He was drawing material constantly from the forests, the flowers, the gardens, and the domestic animals in the fields and in the house, and using them most effectively in his sermons and speeches,” recalled Republican politician Chauncey M. Depew.1

As a speaker, wrote biographer Joseph R. Howard, Rev. Beecher was “always ready, hearty, sincere, with a purpose intelligently put, intelligently carried out.”2 Howard wrote: “He preached without notes and talked as if inspired. His prayers were poems. His illustrations were constant and always changing. He kept his people wide awake and made them feel his earnestness.” Howard, who was a member of Beecher’s Plymouth Church, literally observed: “His acting power was marvelous. Those who knew him well will remember that when talked he could with difficulty sit still. He almost invariably rose, and in the excitement of description or argument acted the entire subject as it struck him.”3

Henry Ward Beecher was “the most accomplished artist of them all if stump oratory was required from the pulpit,” wrote Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg.4 He was a prolific speaker and those speeches became the basis for published works. Among Beechers’ books were Lectures to Young Men and the Plymouth Collection of Hymns, Norwood, a Novel of New England Life, and Star Papers. Rhetorical expert Halford R. Ryan called Beecher “the North’s vox populi on slavery.”5 That was particularly the case when Beecher lectured in England in 1863 on behalf of the North’s cause.

Beecher had a strong independent streak and a strong commitment to political and social reform. Like his novelist sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Beecher had a dramatic flair. “In 1848 Henry Ward Beecher began the practise of selling slaves for liberty, first in the Tabernacle in New York and later from the pulpit of his own church. This he did not only to help individual slaves to win their liberty but to dramatize before the public the evils of slavery very much as did his sister in Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” wrote Lyman Beecher Stowe.6

“It was Mr. Beecher’s genius to create that public sentiment which underlies and gives force to political action in a democracy, and to give effective and eloquent expression to that sentiment when it had been created. To this work he gave himself with singleness of purpose, for he understood the mission to which he had been called better than any of his critics, better than some of his eulogists,” wrote Beecher biographer Lyman Abbott.7 Shortly before Mr. Lincoln visited Plymouth Church in February 1860, Beecher conducted one of his most publicized church services — auctioning off a 9-year-old slave girl nicknamed “Pinky,” who had been brought from Virginia to Brooklyn specifically so she could be sold off into freedom. Not only did Beecher raise the required $900 for freedom, but also an additional $1100 for the education of the girl, whose real name was Rose Ward Hart.

About two weeks later, the day before delivering the Cooper Union speech on February 27, Mr. Lincoln attended services at Beecher’s church. Henry Ward Beecher had a “flaming, demonstrative nature,” according biographer Paxton Hibben.8 Mr. Lincoln liked energetic preaching and had long admired Rev. Beecher. Mr. Lincoln’s law partner, William H. Herndon, often gave him speeches by Beecher and other abolitionist preachers. Artist Francis B. Carpenter wrote that President Lincoln “once remarked to the Rev. Henry M. Field [probably Henry W. Bellows], of New York, in my presence, that ‘he thought there was not upon record, in ancient or modern biography, so productive a mind, as had been exhibited in the career of Henry Ward Beecher!'”9

The Brooklyn pastor was a prominent political as well as polemical figure. He “always had one foot in heaven and the other in politics,” wrote Chase family chroniclers Thomas Graham Belden and Marva Robins Belden.10 Historian David Cheesebrough wrote: “The more popular a preacher, the more likely it is that he or she mirrors the hopes and fears of a significant number of people. Paxton Hibben has written that Henry Ward Beecher, the most popular preacher in the mid—nineteenth—century America, was ‘a barometer and record’ of his times. ‘He was not in advance of his day,’ wrote Hibben, ‘but precisely abreast of his day. Indeed, one can trace the development of Northern thought on slavery by observing the evolution of Beecher’s sermons on the same subject.”11 Abbott wrote that “it would be a mistake…to suppose their either Mr. Beecher or Plymouth Church was what is ordinarily called popular. If he was the most admired orator and the most beloved preacher of his time, he was also the most bitterly hated, excepting on Theodore Parker. No language was too bitter, no epithets too stinging to be applied to him.”12

“Mr. Beecher was one of the few preachers who was both most effective in the pulpit and, if possible, more eloquent upon the platform,” recalled Republican politician Chauncey M. Depew. “When there was a moral issue involved he would address political audiences. In one campaign his speeches were more widely printed than those of any of the senators, members of the House, or governors who spoke. I remember one illustration about his dog, Noble, barking for hours at the hole from which a squirrel had departed, and was enjoying the music sitting calmly in the crotch of a tree. The illustration caught the fancy of the country and turned the laugh upon the opposition.”13

Beecher himself caught the popular imagination. Biographer Howard wrote: “He wore his hair long, no beard was permitted to grow, and a wide Byron collar was turned over a black silk stock, and his clothes were of conventional cut. His hair was thick and heavy. His eyes were large and very blue. His nose was straight, full and prominent. His mouth formed a perfect bow, and when the well-developed lips pared they disclosed the regular, well-set teeth. There was nothing clerical in his face, figure, dress or bearing. He was more like a street evangel — a man talking to men and standing on a common level.”14

Contemporary biographer Joseph Howard wrote that after the 1860 Republican National Convention, Beecher visited the offices of the New York Times and told editor Henry J. Raymond, a Seward supporter: “You man, I know the people of this country at heart better than you do. Your friend Seward has too much heard and too little heart too succeed in any such crisis as this.” To which Raymond replied, “And yours I fear, has too much heart and too little head for such a crisis as will assuredly be precipitated.” Rejoined Rev. Beecher: “Trust then in God and keep your powder dry…”15

Biographer Lyman Beecher Stowe wrote: “As soon as Lincoln was nominated Beecher campaigned for him just as he had for Fremont. After his election and after the outbreak of the war, Beecher, loyally supported by his church, consecrated his every resource to the winning of the war. He preached, he lectured, he wrote editorials. He had become the editor of The Independent. He told his wife to use for the cause his salary, by now an ample one, and all his income from his writings and lectures beyond their living necessities.”16

During Mr. Lincoln’s 1860 election campaign and 1861 transition to the President, wrote biographer Lyman Abbott, there is no evidence that “Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Beecher had any understanding or any correspondence with each other; but what Mr. Lincoln said in occasional private letters Mr. Beecher said with vigor from the pulpit, on the platform, and from the press. Mr. Beecher was not a diplomat; he had no skill in political arts; he did not know how to propose a scheme to blind the eyes of his opponents and to tide over a difficulty, — a scheme to be abandoned as soon as the crisis was passed.” Abbott wrote that he was unable “to find any historical evidence that [Beecher] was ever” an advisor to President Lincoln.17

Indeed, Beecher was often militant and sometimes derisive — occasionally at President Lincoln’s expense. According to biographer Halford R. Ryan, “Beecher was something of a self—appointed critic of the Lincoln administration throughout the war. His evaluations of the president’s administration mellowed especially after the Emancipation Proclamation. Representative of this kind of oratory was a lecture entitled a Visit to Washington During the War….Most of the lecture was of the self—congratulatory nature. Since Lincoln did not bother to see Beecher when he visited Washington in 1861, Beecher coyly allowed that he knelt on the grounds of the White House lawn and prayed for the president and the country.”18

Beecher’s admiration for President Lincoln continued to be intermittent during the Civil War. Historian Allan Nevins wrote that in 1861—1862 “Henry Ward Beecher, temporarily editing the Independent, told its great body of churchgoing readers that neither Lincoln nor the cabinet had furnished any kindling inspiration, for they had let Fear prove stronger than Faith. ‘Not a spark of genius has he [Lincoln]; not an element of leadership; not one particle of heroic enthusiasm.'”19 According to biographer Lyman Beecher Stowe: “like most of the President’s contemporary critics he had, and indeed could have, little conception of the all but insuperable difficulties with which he was faced. Beecher, rightly perceiving that slavery was the underlying cause of the war — in the sense that without slavery there would have been no war — demanded the emancipation of the slaves — so the war might openly and frankly be fought against slavery and for freedom.”20

Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote Beecher’s criticism had an impact: “Beecher’s reiterated low rating of Lincoln’s mental quality became proverbial in some quarters, made a peg upon which to hang deprecation or persiflage, the New York Herald offering: ‘President Lincoln gives unmistakable evidence that the small amount of intellect with which Henry Ward Beecher credits him (and what ‘loyal’ man ‘engaged in the interests of God and humanity’ will dispute the estimate of Beecher?) is gradually failing under the President’s anxiety for renomination.”21

Although sometimes he did not actively back President Lincoln, Beecher backed the war effort. Attorney George Templeton Strong wrote in late November 1863: “Last evening H. W. Beecher spoke again at our Academy of Music. Proceeds for benefit of Sanitary Commission. The tickets had been put too high, three dollars for reserved seats, and it was a vile rainy night — rebel weather — so the house was thin and our net proceeds will not exceed two thousand one hundred dollars, or about one—half what we counted on. The speech was admirable and well received. I adjourned with [Dr. William H.] Van Buren to Dr. [Henry W.] Bellows’s, where were the orator and some half—dozen others, including Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe, whom I found very bright and agreeable. Her brother is also a most interesting talker.”22

Beecher sometimes berated the President and sometimes backed him. “All of Henry Ward Beecher’s doubts of the authority of the central government constitutionally to abolish slavery by naked decree, which had kept him silent on the subject of slavery so many years, suddenly evaporated under the influence of immeasurable war,” wrote biographer Hibben. “On this he hammered away, week after week, in pulpit and out: the end of slavery must be decreed. Almost over night he became as radical as [William Lloyd] Garrison, and carried Universal Emancipation in capital letters in The Independent, as his program. “All men are born equal, and have certain inalienable rights — LIFE, Liberty, and PROPERTY,’ he declares. But the three billion dollars’ worth of slave property which constituted the principal wealth of the South could and should, he felt, be wiped out with a gesture.”23 Biographer Paxton Hibben noted that Beecher’s irritation was not limited to President Lincoln. “Henry Ward Beecher scarcely seemed content unless engaged in acrimonious controversy with some one, from William Cullen Bryant, of the New York Evening Post, to John Mitchell, the Irish patriot.”24

Beecher himself recalled: “I wrote a series of editorials addressed to the President (three or four), and as near as I can recollect they were in the nature of a mowing machine — they cut at every revolution — and I was told one day that the President had received them and read them through with very serious countenance, and that his only criticism was: ‘Is thy servant a dog?’ They bore down on him very hard.”25 Among Beecher’s published comments was one made in August 1862: “We have been made irresolute, indecisive and weak by the President’s attempt to unite impossibilities; to make war and keep the peace; to strike hard and not hurt; to invade sovereign States and not meddle with their sovereignty; to put down rebellion without touching its cause….”26

In 1864, Beecher observed of Mr. Lincoln in The Independent : “It would be difficult for a man to be born lower than he was. He is an unshapely man. He is a man that bears evidence of not having been educated in schools or in circles of refinement.”27 The weekly Independent had been purchased by a parishioner, Henry C. Bowen in 1860. Beecher had become editor, but most of the publication’s editorial work was done by his assistant, Theodore Tilton.

According to Andrew A. Freeman, “During the Civil War, there were rumors that Lincoln, when in a melancholy mood, would come to New York and at night surreptitiously slip over to Plymouth Church to receive the ministrations of Henry Ward Beecher. Of the origin of that myth, Sinclair Lewis wrote: ‘Beecher confided to many visitors that he was always glad to pray with Lincoln and to give him advice whenever the President sneaked over to Brooklyn in the ark.'”28 William J. Wolf reported in his study of Mr. Lincoln’s religious practices: “According to a grandson of Henry Ward Beecher who claimed to have heard it from Mrs. Beecher ‘in her old age,’ Lincoln after the disaster of Bull Run appeared at their Brooklyn door with his face hidden in a military cloak. Without giving his name he asked to see the famous preacher. The anxious Mrs. Beecher at her husband’s bidding admitted the suspicious character. Behind closed doors she heard their voices and the pacing of their feet until the mysterious visitor left about midnight. Shortly before Beecher’s death he is supposed to have revealed that his caller was Lincoln in disguise.

“Alone for hours that night, like Jacob of old, the two had wrestled together in prayer with the God of battles and the Watcher over the right until they had received the help which He had promised to those that seek his aid.”29

Biographer Lyman Beecher Stowe, a member of the Beecher family, reported: “This story has been affirmed and denied by an approximately equal number of reliable persons. Since it seems to be reasonably well established that at the time alleged the President was in New York conferring with some of his generals I am disposed to believe it. It seems to accord with both Lincoln’s informality and his shrewd sense that he should have sought opportunity for an undisclosed talk with such a powerful molder of public opinion. And certainly Beecher’s attitude toward the President and his policies grew from then on constantly more understanding until they came into complete agreement.”30 Historian John W. Starr, Jr., reviewed the evidence and noted that the main arguments against the joint prayer stories were:

First. According to the statement the story was never told by Mr. Beecher until more than twenty years had elapsed, this secrecy was incompatible with Mr. Beecher’s temperament.

Second. That not knowing whether the muffled visitor was ‘a lunatic, an acquaintance, a friend or a foe,’ the fact that it was alleged that Mr. Beecher asked that the stranger be ‘shown up’ militated against its acceptance….

Fourth. The allegations that Lincoln traveled alone’ ‘in disguise’ and ‘by night’ were not worthy of belief

And finally… William O. Stoddard, one of Lincoln’s secretaries then living, stated that ‘it was absolutely impossible for Lincoln to be absent six hours, or hardly one hour, day or night, without one of six persons knowing it, and any one of these would have told the others,’ and as he being one of the six had heard nothing concerning it, the story was ‘incredible, impossible.’31

Emanuel Hertz believed the story, writing in Abraham Lincoln: A New Portrait that it was understandable that Beecher did not speak of the incident. “How could he be expected to confide to any human being the struggle with the angel of light and leading, that he had succumbed, that he saw a new vision, which he had not seen, that God was beckoning and calling — and he had not seen, and he had not heard?” wrote Hertz. “No! Beecher could not be expected to talk of the supernatural happenings of that night.”32

But according to religious historian Wolf, “The really decisive evidence against it was provided by Beecher himself. Along with others, he was asked to contribute reminiscences of Lincoln to the North American Review. He never described anything remotely resembling this Nicodemus visit and said he really did not know Lincoln very well personally.”33 Indeed, Beecher wrote: “My acquaintance with Lincoln could hardly be called an acquaintance. I was rather an observer. I followed him as I did every public character during the antislavery conflict. The first thing that really awakened my interest in him was his speeches parallel with Douglas in Illinois, and indeed it was that manifestation of ability that secured his nomination to the Presidency.”34

Beecher’s most important services for President Lincoln were more diplomatic than religious. “On May 30, 1863, he sailed for Europe for what was intended to be a well-earned vacation — but came to be the occasion of the most important single service he ever rendered to his country,” wrote biographer Abbott. Beecher “had overworked himself to the point that he was sent to Europe in the summer of 1863 by his congregation in order to regain his strength,” wrote Halford Ryan. “All authorities agree that his trip was not a covert cover, nor was it originally sanctioned or intended to be so by the Lincoln administration, for him to speak in behalf of the North or against slavery.”35

But that is what happened. Beecher wrote “I went to England in 1863, not directly or indirectly by request of Mr. Lincoln or of Mr. Seward, and was opposed to speaking there until I was dragged into it by things over there,” wrote Beecher later.36 He very reluctantly agreed to give speeches explaining the situation in America. “If by oratory we mean power to produce a real and enduring effect on a great audience, and if the greatest test of oratory is conquering a hostile audience and producing a permanent effect upon the hears in spite of their hostility, then Mr. Beecher’s five orations in England take deserved place among the great forensic triumphs of the world,” Abbott wrote.37 “He was hissed, interrupted, insulted, but his imperturbable good humor, readiness of wit, matchless moral courage, power of argument, and eloquence of speech, carried everything before him, enabling him to place before the English public a fair view of the situation in America, which, rightly presented, was such as to insure the heartiest sympathy and support for the North,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt.38

Beecher spoke at Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Liverpool and London to sometimes enthusiastic, sometimes raucous crowds. As was his usual practice, Beecher had been prepared to deal with hecklers and abuse. According to Lyman Beecher Stowe: “These five speeches were actually one speech delivered in five parts. In the first at Manchester he gave the history of slavery in America and developed his theory that the war was merely a violent phase of the incessant and inevitable struggle between slavery and freedom. In the second, at Glasgow, he showed how slavery brought labor into contempt and reduced the free working man by its ruinous competition to miserable poverty. In the third at Edinburgh, he explained how the nation had been ruled by the South in behalf of slavery, and when the Lincoln administration came in and they found they could no longer rule, they rebelled. In the fourth at Liverpool, he pointed out ‘that this attempt to cover the fairest portion of the earth with a slave population which buys nothing and a degraded white population that buys next to nothing, should array against it the sympathy of every true political economist and every thoughtful and farseeing manufacturer as tending to strike at the vital want of commerce — not the want of cotton, but the want of customers.'”39

“‘Why do Americans attack us and not France?’ many Englishmen asked H.W. Beecher on his visit in 1863,” wrote historian Allan Nevins. “‘Because,’ he replied, ‘we in our deepest hearts care for England, and not much for France.'”40 In his farewell speech in Liverpool England on October 30, 1863, Reverend Beecher said:

I will not dwell upon the moral power stored in the names of those young heroes that have fallen in this struggle. I cannot think of it but my eyes run over. They were dear to me, many of them, as if they had carried in their veins my own blood. How many families do I know, in which once was the voice of gladness, in which now father and mother sit childless! How many heirs of wealth, how many noble scions of old families, well cultured, the heirs to every apparent prosperity in time to come, flung themselves into their country’s cause, and died bravely fighting for it. And every such name has become a name of power, and whoever hears it hereafter shall feel a thrill in his heart — self—devotion, heroic patriotism, love of his kind, love of liberty, love of God. I cannot stop to speak of these things; I will turn myself from the past of England and of America to the future.

It is not a cunningly—devised trick of oratory that has led me to pray God and His people that the future of England and America shall be an undivided future and a cordially united one. I know my friend Punch thinks I have been serving out ‘soothing syrup’ to the British Lion. Very properly the picture represents me as putting a spoon into the lion’s ear instead of his mouth; and I don’t wonder that the great brute turns away so sternly from the plan of feeding. If it be an offence to have sought to enter your mind by your nobler sentiments and nobler faculties, then I am guilty.

I have sought to appeal to your reason and to your moral convictions.

I have, of course, sought to come in on that side in which you were most good-natured. I knew it, and so did you, and I knew that you knew it; and I think that any man with common-sense would have attempted the same thing. I have sacrificed nothing, however, for the sake of your favor, and if you have permitted me to have any influence with you, it was because I stood apparently a man of strong convictions, but with generous impulses as well. I was because you believed that I was honest in my belief, and because I was kind in turn toward you. And now when I go back home I shall be just as faithful with our ‘young folks’ as I have been with the ‘old folks’ in England. I shall tell them the same things that I have said to their ancestors on this side. I shall plead for Union, for confidence. For the sake of civilization; for the sake of those glories of the Christian church on earth which are dearer to me than all that I know; for the sake of Him whose blood I bear about, a perpetual cleansing, a perpetual wine of strength and stimulation; for the sake of time and the glories of eternity, I shall plead that mother and daughter — England and America — be found one in heart and one in purpose, following the bright banner of salvation, as streaming abroad in the light of the morning it goes round and round the earth, carrying the prophecy and the fulfilment together, that ‘The earth shall be the Lord’s and that his glory shall fill it as the waters fill the sea.’41

Beecher’s British speeches had a profound impact. “These speeches of Mr. Beecher’s, a stranger in a strange country, to hostile audiences, were probably as extraordinary an evidence of oratorical power as was ever known. He captured audiences, he overcame the hostility of persistent disturbers of the meetings, and with his ready wit overwhelmed the heckler.” wrote friend Chauncey M. Depew.42 Lincoln biographer Emmanuel Hertz wrote that “after reading those speeches, five of them which Beecher delivered in England, [President Lincoln ] said to his Cabinet toward the end that if war was ever fought to a successful issue there would be but one man — Beecher — to raise the flag at Fort Sumter, for without Beecher in England there might have been no flag to raise.”43 And raise the flag Beecher eventually did on the day President Lincoln was assassinated.

Biographer Joseph R. Howard wrote”that when Henry Ward Beecher returned from England he could have claimed any reward in the gift of the government, but he preferred for his reward the gratitude of the nation and the affectionate demonstrations of his fellow—citizens. He simply resumed his work, in its several lines, and continued the success of his life. As the war wore on with his ups and downs, its triumphs and its infamies, the question of presidential candidates came up. He was outspoken in his advocacy of Mr. Lincoln’s re-nomination, and in the following campaign did much to secure the re-election of the man in whom he had supremest confidence from first to last.”44

Mr. Lincoln understood it was better to placate than to provoke Beecher. On August 23, 1864, President Lincoln pardoned the same biographer, Joseph R. Howard, the city editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Howard was well—known and unpleasantly known by Mr. Lincoln trouble. He was a reporter for the Republican New York Times when President—elect Lincoln snuck through Baltimore early in the morning of February 23, 1861, and erroneously reported that Mr. Lincoln ‘wore a Scotch plaid cap and a very long military cloak so that he was entirely unrecognizable.”45 Howard subsequently worked for the Democratic New York World where he fanned the anti-draft feelings in the city. Robert S. Harper wrote in Lincoln and the Press: “Howard was a baldish, pale, slender man about thirty-five years old. He was of medium height, had dark eyes, and wore a mustache. With a recognized talent for writing, he held a series of good jobs, first with the Boston Journal.” According Harper, Howard’s co-conspirator, Francis A. Mallison, confessed that “he and Howard met in a private home in Brooklyn on the night of May 17 and that he prepared the forged proclamation in Associated Press style from Howard’s dictation. He said they separated about eleven o’clock and that he took the copy to New York and directed its distribution to the newspapers.”46

On May 18, 1864, according to Lincoln biographer William E. Barton, “Howard “was a member of Plymouth Church and had reported many of the sermons of Henry Ward Beecher. He knew thoroughly the habits and customs of the newspaper offices in New York. He had suffered financial reverses, and he undertook this despicable plot in the assurance that it would cause a panic on Wall Street, from which there would be prompt recovery of prices when the truth was known. His relations with New York brokers were such that he hoped to make a future in a few hours.”47

When word of the fraud had reached Washington, the Lincoln Administration ordered the suppression of the Journal of Commerce and the World, the only two papers which published the phoney proclamation — both of which happened to be Democratic in orientation. Manton Marble, the editor of The World, bitterly complained about the suppression of his newspaper for a crime which had been committed by a Republican congregant of a Republican preacher. In words addressed to President Lincoln, Marble wrote that “Mr. Howard has been from his very childhood an intimate friend of the Republican clergyman, Henry Ward Beecher, and a member of his church. He has listened year in and year out to the droppings of the Plymouth sanctuary. The stump speeches which there follow prayer and precede the benediction he for years reported in the journal which is your devoted organ in this city….he represents himself a favorite visitor at the White House since your residence there.”48

Howard was imprisoned in New York harbor in Fort Lafayette from May to August 1864 — during which Howard remained unrepentant. From jail, he wrote critical and satirical articles about the Lincoln Administration. But Howard’s father was a good friend of Rev. Beecher so the minister extended his plea for Howard’s release in a letter he wrote to a mutual friend: “I feel e[ar]nestly desirous that this lesson should turn to young Howard[‘]s moral benefit. He needed some such prostration — and I am glad to perceive that the sting of his punishment, is the imputation of a treasonable intent. He was the tool of the man who turned states evidence and escaped; & Joe, had only the hope of making some money, by a stock brokers lie & had not foresight or consideration enough to perceive the relation of his act to the public welfare — You must excuse my earnestness. He has been brought up in my parish & under my eye and is the only spotted child of a large family.”49

Mr. Lincoln responded to Beecher’s plea and asked Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to order his release. Mr. Lincoln inquired of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton: “I very much wish to oblige Henry Ward Beecher, by releasing Howard; but I wish you to be satisfied when it is done. What say you?”50 To Mr. Lincoln’s inquiry, Stanton required, “I have no objection if you think it right and this a proper time.”51 Rev. Beecher wavered in his support of President Lincoln, but by the end of September 1864, according to historian Burton J. Hendrick, Beecher “waxed as fervent in praise as he had previously wailed in detraction.”52 Perhaps ironically, the day that President Lincoln authorized Howard’s release was also the day he apparently came to the conclusion that he would not be reelected; Mr. Lincoln had his Cabinet place their signatures on a memo pledging to finish the war before a new Administration took over.

Historian Don C. Seitz noted: “Beecher was one of Lincoln’s staunchest supporters and was much heard from during the campaign. He could be a parson and a politician at the same time, with equal success.”53 In this case, Beecher the parson hurt Beecher the politician. Critical journalists skewered Beecher’s relationship with Howard and his release. Biographer Hibben wrote: “Nevertheless, the incident was not without its value to Henry Ward. He had made and sealed his peace with Lincoln, and got into friendly touch once more with Washington. Theodore Tilton was on familiar terms with the President — Old Abe had kissed Tilton’s little daughter and unbosomed himself on the state of the country in an hour’s private conference with Theodore. Now Henry Ward felt that he too had the entrée to the White House, and when Congress was on the point of adopting the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, there he was, sure enough, congratulating the President just as the right moment to appear with Lincoln at the White House to share with the President the cheers of the crowd.”54

Without any evident irony, Howard wrote in his biography of Beecher several decades later: “On one occasion, when a friend of his had been arbitrarily arrested and confined without process of law, or trial, in a State where there was no necessity for martial law, and where no such thing existed, he went straight to Washington. The President and his Cabinet were in session; the presentation of his card secured an immediate audience. Flaming with indignation he arraigned the President and his Cabinet for their cowardice in permitting outrages in the North, where there was no occasion for interference with local law. Turning to him, with his caustic manner and severe tone, Mr. Seward said, ‘Mr. Beecher, your friend, and others like him, are fomenting disturbance in the North and upsetting all discipline.’ Quick as a flash Mr. Beecher retorted, ‘No, sir, it is you and your little bell that are subverting discipline and causing dissatisfaction in the North.'” Howard wrote:

This allusion to the ‘little bell,’ though not understood possibly now, was broad and pointed then, when the whim, caprice or necessity as the case might be, of a moment sent men, singly or in squads, as prisoners to the nation’s Bastiles upon the tinkle, as it were, of an official bell.

A heated discussion ensued, and late in the day, when dining together, the President said, ‘Mr. Beecher, I have not enjoyed a speech like that since I heard you years ago in old Plymouth. How would you like to be a chaplain to the Cabinet?’ Suffice it that Mr. Beecher gained his point, and abundant apology and compensation followed for the aggrieved party.55

After Howard’s release, Beecher turned his invective on President Lincoln’s Democratic opponent, George B. McClellan. In New York in October 1864, Beecher gave a speech in which he proclaimed: “Two years of war and we have conquered half the rebel territory, hold the keys of the whole, and have nearly destroyed the military strength of the Rebellion in the field. All this in two years of war.” He was interrupted by a heckler who shouted: “Four years you mean.” Beecher took the interruption in stride and responded: “No, I said two years of war. In the first two, General McClellan was in command.”56

Rev. Beecher visited President Lincoln at the White House in early 1865 after word leaked out that Francis P. Blair Sr. had gone to Richmond to visit Confederate President Jefferson Davis. As Beecher described President Lincoln, “His hair was ‘every way for Sunday.’ It looked as though it was an abandoned stubble—field. He had on slippers and his vest was what was called ‘going free.’ He looked wearied and when he sat down in a chair looked at though every limb wanted to drop off his body.”57 Rev. Beecher said to the President: “Mr. Lincoln, I come to you to know whether the public interest will permit you to explain to me what this Southern commission means.” President Lincoln “listened very patiently and looked up to the ceiling for a few moments and said: ‘Well, I am almost of a mind to show you all the documents.” And Mr. Lincoln proceeded to show him a small card that stated: “‘You will pass the bearer through the lines ‘(or something to that effect)” The President told him that “Blair thinks something can be done, but I don’t, but I have no objection to have him try his hand. He has no authority whatever but to go and see what he can do.”58 Beecher subsequently wrote President Lincoln a letter replete with Beecher’s peculiar notions of capitalization:

The interview and information which you gave me, not only relieved me then, but has, ever since, given me great faith. Even your unexpected visit to Ft Munroe, did not stagger me. It has been much criticised. The pride of the nation, is liable to be hurt. Anything that looks like the humiliation of our Government, would be bitterly felt.

But, I do not criticise it. Knowing the ground on which you stand, and the bases of any negotiation, I am more than willing that, as you will sacrifice no substantial Element you should wave any mere formality and So that the inside of the hand is solid bone, I am willing to have the outside flesh soft as velvet—

And I clearly perceive, that, whether you gained any point with the South or not, by going the very Extraordinary step, of the Head of a Nation, leaving the Capital, and going to the rebels, is an act of Condescension which will stop the mouths of northern Enemies.

No man on Earth, was Ever before so impregnably placed, as you are. Look at the facts.

1. The South is exhausted are and defeated. The military result is sure.

2. Every step which you have, one by one taken, toward emancipation & national liberty, are is now confirmed beyond all change

3. You have brought the most dangerous and Extraordinary rebellion in history, not only to a successful End, but, have done it without sacrificing republican Gover[n]ment Even in its forms. It is wonderful, and a sign of Divine help, that democratic institutions & feelings, are stronger today, — after four years of War, and military administration not less as Enlarged than as when all Europe was one Camp, — than when you began.

The north is renovated, Heresy is purged out, Treason is wounded to the death. The Constitution has felt the hand of God laid upon it, as He said, “Be thee clean” & the leprosy is departed[.] You have now done all that your Enemies, Even, could ask to shew your desire for peace, & more than many of your friends could wish.— Your position is Eminent & impregnable. I am only anxious that you should not lose that place. I do not believe that you will. But it is more dangerous to make peace than to make War.

Why then do I write to you?

1. Because, it seemed to me, that a man in public office, seeing chiefly political & official people, might be cheered to hear from a private citizen, seeking no office, and having no political ends, except such as all good Citizens have.

2. Because, I wish to suggest, that these rumors of peace, and this feverish suspense about Commissioners & negotiations, is injurious, in so far as replenishing the Army is concerned, — It takes off the sense of responsibility. It leads men to think that things are so nearly Ended that it will make no difference whether the Army is recruited or not—

Would it not be well if the Country could be told, deffinitely [sic] how the case stands.? One address to the Army, or to the nation, declaring that peace can come only by Arms, if in your judgement the fact is so, would end these feverish uncertainties & give the Spring Campaign renewed Vigor—

My dear Mr. Lincoln, I have written to you, as a friend to a friend. I am grateful to God, for raising you up. I believe that you are in His hand. That he may guide you is my daily & almost hourly prayer—

I hope that it will not seem intrusive in me to write to you.— If I add nothing to your wisdom, I might I hope, sometimes cheer you under your great cares59

Beecher had a talent for public relations as well as for personal self-aggrandizement. Biographer Hibben wrote that “when the President acknowledged two of these voluminous communications with a brief courteous note, Henry Ward spoke in Plymouth Church of ‘the last letter I received from him’ as if it were part of an intimate and highly confidential relationship.”60 What a slender reed Beecher was leaning on is revealed by President Lincoln’s letter: “Yours of the 4th and the 21st reached me together only two days ago. I now thank you for both. Since you wrote the former the whole matter of the negotiations, if it can be so called, has been published, and you, doubtless, have seen it. When you were with me on the evening of the 1st I had no thought of going in person to meet the Richmond gentlemen.”61

Family biographer Lyman Beecher Stowe wrote: “During the closing weeks of the war, Secretary Stanton wired Beecher after every important development. On Sunday morning, April 2, 1865, in Plymouth Church, just after the sermon, a telegram from Secretary Stanton was handed to Beecher in the pulpit announcing decisive Union victories after three days of hard fighting. After reading it aloud Beecher asked the thousands present to turn to America. [in their hymn books]. The great company, realizing that the war was practically over, sang the noble anthem with stream eyes.”62 A few days later, Rev. Beecher sailed for Charleston, South Carolina with General Robert Anderson, the Army officer who had commanded Fort Sumter before its surrender on April 14, 1861. On April 14, 1865, the day President Lincoln was assassinated, Beecher and Anderson were in Charleston to commemorate the war’s beginning and end.

Eight days after President Lincoln’s death, Beecher delivered a funeral oration which biographer William E. Barton called “one of the most eloquent of all perorations in the history of modern funeral oratory.” According to biographer Halford R. Ryan, “Beecher appropriately chose a text from Deuteronomy that related how Moses was led by God to the top of Mount Pisgah. From there, God allowed Moses to see the Promised Land in the distance but was not permitted to enter it. That passage served as an analogy for the slain sixteenth president. Beecher portrayed the irony of the war that Lincoln was not allowed to witness the great moral and political victory of his presidency to save the Union.”63

Beecher shifted quickly with the mood of the country. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote that Beecher “threw himself with a wild—flowing vitality into the occasion. Nothing now of that remark of his in Charleston a few days earlier that Johnson’s little finger was stronger than Lincoln’s lions. The nation, in grief over the unburied one whose funeral procession was yet to move, wanted consolation, psalms of praise for the dead, and dirges of woe for the sorrowing.”64

And now the martyr is moving in triumphal march, mightier than when alive. The nation rises up at every stage at his coming. Cities and states are his pall—bearers, and the cannon speaks the hours with solemn progress. Dead, dead, dead, he yet speaketh. Is Washington dead? Is Hampden dead? Is any man that was ever fit to live dead? Disenthralled of flesh, risen to the unobstructed sphere where passion never comes, he begins his illimitable work. His life is now grafted upon the infinite, and will be fruitful as no earthly life can be. Pass on, thou that has overcome! Your sorrows, oh people are his peace! Yours bells, and bands, and muffled drums, sound triumph in his ear. Wail and weep here; God makes it echo joy and triumph there. Pass on!

Four years ago, oh, Illinois, we took from your midst an untried man, and from among your people. We return him to you a mighty conqueror. Not thine any more, but the nation’s; not ours, but the world’s. Give him place, oh, ye prairies! In Midst of this great continent his dust shall rest, a sacred treasure to myriads who shall pilgrim to that shrine to kindle anew their zeal and patriotism. Ye winds that move over the mighty places of the West, chant his requiem! Ye people, behold the martyr whose blood, as so many articular words, pleads for fidelity, for law, for liberty.”65

Years later, Beecher concluded that “the nomination of Lincoln was, to begin with, the revelation of the hand of God. He was, in the most significant way, a man that embodied all the best qualities of unspoiled, middle—class men. He had the homely common sense; he had honesty with sagacity; and he had sympathetic nature that prepared him to accept any stormy times.”66

Beecher gave up his Independent editorship in 1864 and subsequently became the editor of The Christian Union. His reputation in later years was marred by his support for President Andrew Johnson, his retreat on the rights of freed slaves, and a scandal initiated by Theodore Tilton, a parishioner who succeeded Beecher as editor of the Independent. Tilton went off on his own journalistically — and off the deep end editorially and personally.

The younger Tilton, who advocated a sort of 19th century version of free love, eventually accused Beecher of seducing his wife, with whom Beecher had spent considerable time when her own husband was out of town. The scandal became public in large part because Beecher attacked Victoria Woodhull, Tennessee Claflin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who were friends and allies of Tilton. Biographer Joseph R. Howard wrote: “It was not long before the Tilton story found its way to the public press, and then it appeared that Tilton charged Beecher with the ruin of his wife, the details of which, he said, he gave. The most extraordinary letters, purporting to be from Beecher to Tilton, or Moulton, were published, and ere long it appeared as if the social structure of Brooklyn in general, and Plymouth Church in particular, had been for years upon the crest of a boiling volcano.”67

“Beecher’s famous trial on charges made by Theodore Tilton against him on relations with Tilton’s wife engrossed the attention of the world. The charge was a shock to the religious and moral sense of countless millions of people. When the trial was over the public was practically convinced of Mr. Beecher’s innocence,” later wrote Republican attorney Chauncey M. Depew.68 Depew’s friendship perhaps skewed his judgment of the 1875 trial. Beecher biographer Paxton Hibben concluded that the “If a jury of his neighbors could not agree that Henry Ward Beecher was not an adulterer, the rest of the country may be forgiven for not being quite certain about it, either.”69 Public faith in Beecher, however, had been shattered. His reputation never recovered.

Beecher’s wife once complained that “a woman who marries a popular favorite must be ready to divide him with the public. It keeps getting worse, though, every year. When I married him I merely had to share him with the congregation, but since then…he has married the Platform and the Press and the Goddess of Liberty, and I miss him a good deal.”70

Footnotes

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 324.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 463.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 92.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 364.

- Halford Ross Ryan, Henry Ward Beecher: Peripatetic Preacher, p. 44.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 278.

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 229.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 144.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 135.

- Thomas Graham Belden and Marva Robins Belden, So Fell the Angels, p. 217.

- David B. Chesebrough, No Sorrow Like Our Sorrow: Northern Protestant Ministers and the Assassination of Lincoln, p. xi.

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 220.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 327-328.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, 134, .

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 270.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 285.

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 228-229.

- Halford Ross Ryan, Henry Ward Beecher: Peripatetic Preacher, p. 38-39.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 301.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 286.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume II, p. 578.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 373 (November 26, 1863).

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 159.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 129.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 249 (Henry Ward Beecher).

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 286.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 184.

- Andrew A. Freeman, Abraham Lincoln Goes to New York, p. 149.

- William J. Wolf, The Almost Chosen People: A Study of the Religion of Abraham Lincoln, p. 26-27.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 287.

- John W. Starr, Jr., “Did Lincoln and Beecher Pray Together?”, p. 1-2 (Reprinted from Christian Advocate, April 22, 1926).

- Emmanuel Hertz, Abraham Lincoln: A New Portrait, p. 105.

- William J. Wolf, The Almost Chosen People: A Study of the Religion of Abraham Lincoln, p. 27.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 247 (Henry Ward Beecher).

- Halford Ross Ryan, Henry Ward Beecher: Peripatetic Preacher, p. 36.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 249 (Henry Ward Beecher).

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 262.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 412.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 289-290.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, 1862-1863, p. 303.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 343-345.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 324-325.

- Emmanuel Hertz, Abraham Lincoln: A New Portrait, p. 106.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 384.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 295.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 296.

- William E. Barton, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 287.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 300 (The World, May 23, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry Ward Beecher to John D. Defrees1, August 2, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 512 (Letter to Edwin M. Stanton, August 22, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 513 (Letter to Edwin M. Stanton, August 22, 1864).

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 456.

- Don C. Seitz, Lincoln the Politician, p. 433.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 168-169.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 351.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 428 (New York Tribune, October 25, 1861).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 249-250 (Henry Ward Beecher).

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 294-295.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry Ward Beecher to Abraham Lincoln, February 4, 1865).

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 169.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Henry Ward Beecher [Copy], February 27, 1865).

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 295.

- Halford Ross Ryan, Henry Ward Beecher: Peripatetic Preacher, p. 43.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 364.

- William E. Barton, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 359.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 247-248 (Henry Ward Beecher).

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 444.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 326.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, .