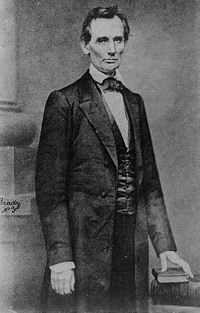

Abraham Lincoln: Before Delivering His Cooper Union Address

Washington Market, 1859

Cassius M. Clay

Joseph Medill

The Cooper Union speech offered Mr. Lincoln an opportunity to define himself before the Eastern mandarins of the Republican Party and to show them that a Westerner had the gravitas to be a presidential contender. “Precisely what Lincoln needed,” wrote Albert Shaw, was the opportunity to show himself before a New York audience of the highest intelligence in his real character as a thorough student of our constitutional history, as a master of diction perfect suited to his theme, and as a man of dignified personality, far removed from the grotesque mountebank about whose uncouthness there had been many rumors afloat.”1

Originally, the lecture invitation came from the lecture committee of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn where Henry Ward Beecher preached. According to Beecher biographer Lyman Abbot, “the Plymouth Church edifice was not idle throughout the week. It was the best auditorium in Brooklyn for public lectures, and was in frequent use. It served as a lecture-hall as well as meeting-house.”2 Andrew A. Freeman wrote in Abraham Lincoln Goes to New York, Henry “Bowen, a wealthy merchant who had founded Plymouth Church and persuaded Henry Ward Beecher to leave a pulpit in Indianapolis to be its pastor, was not a member of the committee that had arranged for Lincoln’s speech. The two men had not met, although Bowen had once retained Lincoln’s law firm to represent him in an Illinois litigation. Lincoln, however, knew The Independent which Bowen started in 1848.”3

Historian Reinhard H. Luthin cited a different source for the invitation: “In the fall of 1859 James A. Briggs, who was working for Chase and cooperating with the anti-Seward forces in New York, invited Lincoln to speak at the Reverend Dr. Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn.”4 Briggs, who served on the lecture committee for Plymouth Church and as a political ally of Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase, had telegraphed Mr. Lincoln on October 12, 1859: “Will you speak in Mr Beechers church Brooklyn on or about the twenty ninth (29) November on any subject you please pay two hundred (200) dollars”.5 What Mr. Lincoln may not have known at the time was that the invitation for the event came from the faction of New York Republicans opposed to the leadership of Senator William H. Seward. In inviting Mr. Lincoln, they were not only doing a service to him, they were attempting to do a disservice to Seward by promoting one of his potential Republican opponents.

Mr. Lincoln’s law partner, William H. Herndon recalled that one morning in October, Mr. Lincoln rushed into their office “with the letter from New York City, inviting him to deliver a lecture there, and asked my advice and that of other friends as to the subject and character of his address. We all recommended a speech on the political situation. Remembering his poor success as a lecturer himself, he adopted our suggestions. He accepted the invitation of the New York committee, at the same time notifying them that his speech would deal entirely with political questions, and fixing a day late in February as the most convenient time. Meanwhile he spent the intervening time in careful preparation. He searched through the dusty volumes of congressional proceedings in the State library, and dug deeply into political history. He was painstaking and thorough in the study of his subject, but when at last he left for New York we had many misgivings — and he not a few himself — of his suc[c]ess in the great metropolis.”6 In response to Mr. Lincoln’s proposal of a political speech, Briggs agreed, writing back:

Your letter was duly received; I handed it over to the Committee, & they will accept your Compromise. And you may Lecture the time you mention, & will pay you $200. I think they will arrange for a Lecture in N. Y. also, and will pay you $200 for that, with your consent. Thus you may kill two birds with one stone.

I understand the time between the 20th and last of February. Let me know about one week or so before the day fixed upon for the first Lecture.

The political cauldron is boiling here. New Jersey will elect Mr. [Charles S.] Olden [as Governor]. Her people are aroused & hard at work.

[Thomas] Corwin is here from Ohio, & he will stir them up to good works. Mr. W[illiam]. L. Dayton is on the stump in New Jersey, doing a Yeoman’s work.

Would that we could have the pleasure of listening to you, before the Campaign closes. I have no doubt of the success of the Republicans in this State. I think it is a mistake that Senator [William H.] Seward is not on his own battlefield, instead of being in Egypt surveying the route of an old Underground Rail Road, over which Moses took, one day, a whole nation, from bondage into Liberty. But, in his own time, he will be heard from, on the “Irrepressible conflict.”

I hope for complete & glorious success in 1860. We must succeed & rescue the Government from its present plunderers.7

On November 13, Mr. Lincoln wrote Briggs about the Brooklyn invitation: “I will be on hand; and in due time, will notify you of the exact day. I believe, after all, I shall make a political speech of it. You have no objection? I would like to know, in advance, whether I am also to speak, or lecture, in New-York.”8 Mr. Lincoln went to work preparing for the lecture for three months, according to law partner Herndon: “Mr. Lincoln obtained most of the facts of his Cooper Institute speech from Elliot’s ‘Debates on the Federal Constitution.’ There were six volumes, which he gave to me when he went to Washington in 1861.”9 Biographer Benjamin Thomas noted that Mr. Lincoln put “in hour after hour at the State Library, where he examined the Annals of Congress and the Congressional Globe and turned interminable pages of old, dusty newspapers as he sat hunched over a table, running his long fingers through his coarse black hair.”10

“No previous effort of his life cost him so much hard work as did that Cooper Institute speech,” wrote William O. Stoddard, an Illinois journalist who worked for President Lincoln in the White House. “When finished, it was a masterly review of the history of the slavery question from the foundation of the government, with a clear, bold, statesmanlike presentation of the then present attitude of parties and of sections. It exhibited a careful research, a thorough knowledge and understanding of political movements and developments, that staggered even the most laborious and painstaking students. It showed a grasp, a breadth, a mental training, and a depth of penetration which compelled the admiration of critical scholars.”11

Meanwhile, plans of the lecture sponsors changed. “In New York, the Young Men’s Central Republican Union, organized for improvement and propaganda, inaugurated a series of lectures at the hall built by Peter Cooper, the New York philanthropist, in the triangle where Third and Fourth avenues form a junction with the Bowery. The famous hall, below the street level and in a deep basement, is very commodious, though dismal,” wrote Historian Don C. Seitz in Lincoln the Politician. “The club was bent on securing high-powered talent and engaged Frank P. Blair of Missouri, Cassius M. Clay of Kentucky, who had made a specialty of defying slavery there, and Abraham Lincoln. The two first had been heard when Lincoln came to the platform on the evening of February 27, 1860, to deliver the ‘lecture’ which, with the Douglas debates and the vote he had received for Vice President four years before at the Philadelphia convention….”12

Republican leaders decided to give Mr. Lincoln a more political forum and on February 9, Mr. Lincoln received a second invitation. Charles C. Nott, who was on the executive committee of the Young Men’s Republican Union, addressed a letter of invitation to Mr. Lincoln on February 9 from the Young Men’s Central Republican Union to deliver “what I may term a political lecture.” Nott wrote: “You are I believe, an entire stranger to your Republican brethern here; but they have for you the highest esteem, and your celebrated contest with Judge Douglas awoke their warmest sympathy and admiration. Those of us who are in the ranks would regard your presence as of very material aid and as an honor and pleasure which I cannot sufficiently express.”13

On February 15, Briggs again wrote Mr. Lincoln: “Your letter was duly recd. The Committee will advertise you for the Evening of the 27th inst. Hope you will be in good health & spirits, as you will meet here in this great Commercial Metropolis a right cordial welcome. The noble [Cassius M.] Clay speaks here to-night. The good cause goes on.”14

Republican expectations for the speech were high, but Springfield’s Democratic newspaper reported a different set of expectations in Mr. Lincoln’s hometown on the eve of his February 23 departure from the Illinois capital: “Significant: The Hon. Abraham Lincoln departs today for Brooklyn under an engagement to deliver a lecture before the Young Men’s Association in that city in Beecher’s church. Subject: not known. Consideration: $200 and expenses. Object: presidential capital. Effect: disappointment.15

As the date of the event neared, the New York Tribune proclaimed: “Abraham Lincoln of Illinois will, for the first time, speak in this Emporium, at Cooper Institute, on Monday evening. He will speak in exposition and defense of the Republican faith; and we urge earnest Republicans to induce their friends and neighbors of adverse views to accompany them to his lecture. The Association which has taken the responsibility of drawing Mr. Lincoln from his Western home and business, to give our citizens this gratification and the Republican cause this aid have deserved well of their compatriots, and we shall wisely encourage them to similar efforts in the future…” The Tribune noted: “In 1858, he was unanimously designated by the Republican State convention to succeed Mr. Douglas in the Senate, and thereupon canvassed the State against Mr. D. With remarkable ability. Mr. Douglas secured a majority of the Legislature and was elected, but Mr. Lincoln had the larger popular vote….” The Tribune described Mr. Lincoln as “emphatically a man of the People, a champion of Free Labor, of diversified and prosperous Industry and of that policy which leads through peaceful progress to universal intelligence, virtue and freedom. The distinguishing characteristics of his political addresses are clearness and candor of statement, a chivalrous courtesy to opponents, and a broad, genial humor. Let us crowd the Cooper Institute to hear him on Monday night.”16

Mr. Lincoln sought some advice along the way from Springfield to New York City. “In connection with this address at Cooper Institute, Joseph Medill has told how Lincoln had visited the Chicago Tribune before the trip to New York, and had asked him and Charles Ray, editor, to look over the manuscript of his speech and submit to him any notes as to changes of verbiage they thought desirable,” wrote William E. Lilly. “Medill adds, describing their methods and the result: ‘One read slowly while the other listened attentively, and the reading was frequently interrupted to consider suggested improvements of diction, the insertion of synonyms, or points to render the text smoother or stronger, as it seemed to us. Thus we toiled for some hours, till the revision was completed to our satisfaction, and we returned to the office early next morning to re-examine our work before Lincoln would call for the revised and improved manuscript. When he came in we handed him our numerous notes with reference places carefully marked on the margins of the pages where each emendation was to be inserted. We turned over the address to him with a self-satisfied feeling that we had considerably bettered the document, and enabled it to pass the critical ordeal more triumphantly than otherwise it would. Lincoln thanked us cordially for our trouble, glanced at our notes, told us a funny story or two of which the circumstances reminded him, and took his leave.'”17

A few days before his leaving for the Cooper Institute address, the Chicago Tribune had printed an editorial declaring for Lincoln for President. Naturally then, Medill and Ray were elated when the New York papers arrived at their office filled with Lincoln’s speech and the words of praise which all carried. For both there was the added pleasure of having had some part in putting the final touches on the now famous speech. Medill adds: ‘Ray and I plunged eagerly into the report, feeling quite satisfied with the successful effect of the polish we had applied to the address. We both got done reading at the same time. With a sickly sort of a smile, Dr. Ray looked at me and remarked, ‘Medill, Old Abe must have lost out of the window of the car all our precious notes, for I don’t find a trace of one of them in his published talk here.’ I tried to laugh and said, ‘This must have been one of his waggish jokes.'”18

Along the way to New York, Mr. Lincoln met Kentucky abolitionist Cassius M. Clay, who had given an address in New York on February 15. Clay wrote that Mr. Lincoln “was invited to speak in New York by the young Whigs and Liberals, and I met him again for the second time, and had on the [railroad] cars a long talk with him on my favorite policy. Lincoln as usual was a good listener; and when I had accumulated all my arguments in favor of liberation he said: ‘Clay, I always thought the man who made the corn should eat the corn.’ This homely illustration of his sentiments has lingered ever in my memory as one of the most eminent arguments against slavery.”19

Footnotes

- Albert Shaw, Abraham Lincoln: The Path to the Presidency, p. 252.

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 220.

- Andrew A. Freeman, Abraham Lincoln Goes to New York, p. 15.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 79.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James A. Briggs to Abraham Lincoln, October 12, 1859).

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 367.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James A. Briggs to Abraham Lincoln, November 1, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 494 (Letter to James A. Briggs, November 13, 1859).

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 368.

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 202.

- William O. Stoddard, Abraham Lincoln: The Man and the War President, p. 174-175.

- Don C. Seitz, Lincoln the Politician, p. 138.

- Albert Shaw, Abraham Lincoln: The Path to the Presidency, p. 251.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James A. Briggs to Abraham Lincoln, February 15, 1860).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 80 (Springfield State Register, February 23, 1860).

- Harlan Hoyt Horner, Lincoln and Greeley, p. 165-166.

- William E. Lilly, Set My People Free, p. 234-235.

- William E. Lilly, Set My People Free, p. 235.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 297 (Cassius M. Clay).