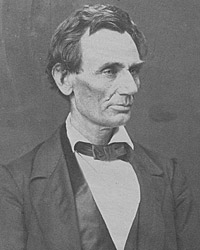

Abraham Lincoln

Jacob Collamer

Robert Todd Lincoln

“The effort was so dignified, and exhibited so much learning and such thorough mastery of the subject, that, coming from a source whence this kind of excellence was not expected, it was a surprise and revelation, and, therefore, made the greater impression. He awoke the next morning to find himself famous,” wrote contemporary biographer and friend, Isaac Arnold. Mr. Lincoln saw the newspaper reaction to his Cooper Union speech before he left New York City to visit his son Robert in Massachusetts. Along the way, Mr. Lincoln gave additional speeches in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Mr. Lincoln wrote Mrs. Lincoln few days into his trip:

When I wrote you before I was just starting on a little speech-making tour, taking the boys with me. On Thursday they went with me to Concord, where I spoke in day-light, and back to Manchester where I spoke at night. Friday we came down to Lawrence — the place of the Pemberton Mill tragedy — where we remained four hours awaiting the train back to Exeter. When it came, we went upon it to Exeter where the boys got off, and I went on to Dover and spoke there Friday evening. Saturday I came back to Exeter, reaching here about noon, and finding the boys all right, having caught up with their lessons. Bob had a letter from you saying Willie and Taddy were very sick the Saturday night after I left. Having no despach [sic] from you, and having one from Springfield, of Wednesday, from Mr. Fitzhugh, saying nothing about our family, I trust the dear little fellows are well again.

This is Sunday morning; and according to Bob’s orders, I am to go to church once to-day. Tomorrow I bid farewell to the boys, go to Hartford, Conn. and speak there in the evening; Tuesday at Meriden, Wednesday at New-Haven — and Thursday at Woonsocket R.I. Then I start home, and think I will not stop. I may be delayed in New York City an hour or two. I have been unable to escape this toil. If I had foreseen it I think I would not have come East at all. The speech at New-york, being within my calculation before I started, went off passably well, and gave me no trouble whatever. The difficulty was to make nine others, before reading audiences, who have already seen all my ideas in print.

If the trains do not lie over Sunday, of which I do not know, I hope to be home to-morrow week. Once started I shall come as quick as possible.

Kiss the dear boys for Father1

Several decades later, Robert Todd Lincoln noted: “After my father’s address in New York in February 1860, he made a trip to New England in order to visit me at Exeter, H.H., where I was then a student in the Phillips Academy. It had not been his plan to do any speaking in New England, but, as a result of the address in New York, he received several requests from New England friends for speeches….”2 Historian Reinhard H. Luthin wrote: “Lincoln calculated the states to visit and the states to avoid in New England, determined not to ruffle the sensitivities of supporters of other presidential contenders. Republican leaders in Massachusetts and Maine were nearly solid for Seward, and Vermont had its favorite son, Senator Jacob Collamer. So Lincoln did not enter these states.”3

Mr. Lincoln stopped in New York City on his way back to Illinois. Briggs said Mr. Lincoln told him: “When I was East, several gentlemen made about the same remark to me that you did today about the presidency; they thought my chances were about equal to the best.”4 Salmon Chase’s agent, James Briggs, wrote Chase: “Mr. Lincoln of Illinois told me that [he] had a very warm side towards you, for of all the prominent Republicans you were the only one who gave him aid and comfort. I urged him by all means to attend the convention. I was pleased with him, paid him all the attention I could, went with him to hear Mr. Beecher and Dr. Chapin. Mr. [Hiram] Barney went with him to the ‘House of Industry’ at the Five Points, and then took him home to tea. He was very much pleased with Mr. Barney.”5 (Barney’s reward was to come a year later when Mr. Lincoln named him to one of the top patronage posts in the country — Collector of Customs for the port of New York.) A teacher at the Five Points House of Industry recalled:

One Sunday morning I saw a tall, remarkable-looking man enter the room and take a seat among us. He listened with fixed attention to our exercises, and his countenance expressed such genuine interest that I approached him and suggested that he might be willing to say something to the children. He accepted the invitation with evident pleasure; and, coming forward, began a simple address, which at once fascinated every little hearer and hushed the room into silence. His language was strikingly beautiful, and his tones musical with intense feeling. The little faces would droop into sad conviction as he uttered sentences of warning, and would brighten into sunshine as he spoke cheerful words of promise. Once or twice he attempted to close his remarks, but the imperative shout of “Go on! Oh, do go on!” would compel him to resume. As I looked upon the gaunt and sinewy frame of the stranger, and marked his powerful head and determined features, now touched into softness by the impressions of the moment, I felt an irrepressible curiosity to learn something more about him, and while he was quietly leaving the room, I begged to know his name. He courteously replied: “It is Abraham Lincoln, from Illinois.”6

“Living conditions in Five Points had improved markedly by the eve of the Civil War, but Lincoln nonetheless found the neighborhood’s abject poverty shocking,” wrote Tyler Anbinder in Five Points. “When he arrived at the House of Industry, Lincoln was undoubtedly given a full tour of the organization’s new six-story brick headquarters, which towered over the surrounding wooden hovels on the north side of Paradise Square just west of the Five Points intersection. It had spacious dormitories where dozens of abused, neglected, or homeless boys and girls lived until they found adoptive parents. His hosts would also have shown him the large chapel where religious services were held and the workshops where neighborhood teens and adults learned a variety of trades.”7

On this return visit to New York, Mr. Lincoln also apparently returned to Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. Artist Francis B. Carpenter wrote that the “church was packed, as usual, and the services had proceeded to the announcement of the text, when the gallery door at the right of the organ-loft opened, and the tall figure of Mr. Lincoln entered, alone. Again in the city over Sunday, he started out by himself to find the church, which he reached considerably behind time. Every seat was occupied; but the gentlemanly usher [Nelson Sizer] at once surrendered his own, and, stepping back, became much interested in watching the effect of the sermon upon the western orator. As Mr. Beecher developed his line of argument, Mr. Lincoln’s body swayed forward, his lips parted, and he seemed at length entirely unconscious of his surroundings, — frequently giving vent to his satisfaction, at a well-put point or illustration, with a kind of involuntary Indian exclamation, — ‘ugh!’ — not audible beyond his immediate presence, but very expressive!”8

When he got home, Mr. Lincoln learned that not everyone greeted his Cooper Union speech with enthusiasm. He felt it necessary to write friend Cornelius Mitchell in early April: ”

Reaching home yesterday, I found yours of 23d. March, inclosing a slip from the Middleport Press. It is not true that I ever charged anything for a political speech in my life — but this much is true: Last October I was requested, by letter, to deliver some sort of speech in Mr. Beechers church in Brooklyn, $200 being offered in the first letter. I wrote that I could do it in February, provided they would take a political speech, if I could find time to get up no other. They agreed, and subsequently I informed them the speech would have to be a political one. When I reached New York, I, for the first [time], learned that the place was changed to ‘Cooper Institute.’ I made the speech, and left for New Hampshire, where I have a son at school, neither asking for pay nor having any offered me. Three days after, a check for $200 — was sent to me, at N.H., and I took it, and did not know it was wrong. My understanding now is, though I knew nothing of it at the time, that they did charge for admittance, at the Cooper Institute, and that they took more than $200.

I have made this explanation to you as a friend; but I wish no explanation made to our enemies. What they want is a squabble and a fuss; and that they can have if we explain; and they can not have if we don’t.

When I returned through New York from New England I was told by the gentlemen who sent me the check, that a drunken vagabond in the Club, having learned something about the $200, made the exhibition out of which The Herald manufactured the articled quoted by The Press of your town.

My judgment is, and therefore my request is, that you give no denial, and no explanations.9

But the good news of the trip as well as the criticism had been spread by Republican newspapers in Illinois. The

Menard Index reported: “Mr. Lincoln’s recent tour through the eastern States has given him a wonderful popularity there. From every place where he has spoken he has received the most flattering encomiums. The enthusiasm which his presence raised in the east is an earnest of that which would be excited by his nomination for the Presidency. There seems to be a strong feeling in favor of nominating Mr. Lincoln in case Douglas is the strongest candidate against Douglas. We believe the same thing is true against any possible nominee, and that he should be nominated in any event. Considering the matter in a local point of view, we look upon the nomination of Mr. Lincoln as securing the State of Illinois to the Republicans for the future, so long as the issues remain the same that they are now. He will most surely carry the State, and with him the State ticket will be elected, the Legislature secured and Senator Trumbull re-elected to his seat in the Senate. While we intend to accomplish this result anyhow, we can in no way be so sure of doing it as by having our ticket headed by Abraham Lincoln for President. In view of the importance of this election to the future supremacy of the Republican party in thus [this] State; we hold that every friend of the party in this State should use every effort to accomplish Mr. Lincoln’s nomination.”

10,/div>

Footnotes

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, First Supplement, p. 49-50 (Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln, March 4. 1860).

- George Haven Putnam, Abraham Lincoln: The People’s Leader in the Struggle for National Existence, p. 48.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 210.

- Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, The Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 39-40 (from James A. Briggs to the New York Post, August 16, 1867).

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, p. 188.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 133-134.

- Tyler Anbinder, Five Points: The 19th-Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum, p. 236.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 134-135.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 38 (Letter to Cornelius F. Mcneill, April 6, 1860).

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Lincoln as They Saw Him, p. 161 (Menard Index reprinted in Illinois State Journal, March 28, 1860).