Patronage in New York was never simple. Not only were there competing Republican factions. There were competing Republican newspapers. And the battles between the political factions also became the battles between newspapers. Historians Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin wrote how the battles played out in June 1864: “For chairman of the Union National Committee, the Baltimore Convention selected Henry J. Raymond, New York member and editor of the New York Times. Raymond’s selection was a distinct victory for the conservative or Seward-Weed forces over the radical or pro-Chase faction among the Empire State Republicans. Raymond’s Times was the New York City mouthpiece of the Weed interest and as such opposed the radical anti-Lincoln organs, Greeley’s New York Tribune and William Cullen Bryant’s New York Evening Post. Hardly had the Baltimore Convention adjourned than a lively press battle opened between Weed and opponents.”1

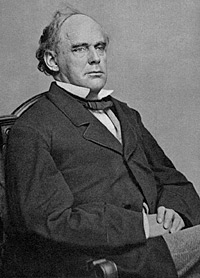

Patronage concerns in New York centered on the New York Custom House, where lucrative positions were controlled by persons loyal to Salmon P. Chase — but where charges of corruption made office-holders vulnerable to calls for their removal. Chase biographer John Niven noted: “The area of greatest concern to Chase was also the area of greatest political friction, the New York custom house, the theater wherein opposing forces within the Republican coalition vied for control of its patronage. Chase’s friend [Hiram] Barney was the collector, and another associate, Henry B. Stanton, was one of the many deputy collectors. The collector had broad powers over procedures, less over direct political patronage.”2 For three years, Thurlow Weed had stewed over the situation. By early January 1864, Barney himself was stewing and wrote President a spirited and detailed defense of his actions:

I have been trying for several weeks to go to Washington but ill health bad traveling and the business of the office have prevented. Now the discovery of the misconduct by my late confidential clerk and others, in connection with the bonding of shipments to neutral ports imposes upon me duties inconsistent with immediate absence from my post — I shall however go there as soon as further investigations shall enable me to dispose of these matters in a satisfactory manner.Mr. Stanton and his son were not permitted to remain in their places one hour after Mr Jordan’s investigations were communicated to me1 Mr [Albert] Hanscom , another Deputy Collector of great experience & capacity was immediately put in charge of Mr Stanton’s bureau with directions to allow no book or paper belonging to the office to be taken from it and to institute a rigid examination of all the files and books of the bureau, and a careful examination of the bonds in connection with the manifests of shipments with a view of determining if the bonds are valid and sufficient to cover all the shipments — There were many thousands of these bonds and Mr Hanscom has besides this examination the charge of the current business of two bureaus, both very important to the interests of the government He has nearly or quite finished the investigations but has not given me his report. I hope to get it on Monday or Tuesday the 12th inst. His labors have been so severe as to impair his health; but he has been relieved since Dec 31st by Mr. Runkle the successor of Mr Stanton. Mr Runkle the Deputy Collector of the 9th Division of the Customs is a lawyer of character & experience— He has charge of all suits and claims against the Government or my self as Collector and the taking of bonds for shipments of cargo. He keeps a register of all such suits and claims and of the proceedings in those and collects the facts and the points of law applicable to these cases for the use of the District Attorney. H He furnishes daily, to Mr Hanscom the Deputy Collector of the 10th Division who has charge of all cases of fines penalties and seizures and all other claims & suits in favor of the Government, a list of the bonds taken by him with a brief description of each— Mr Hanscom delivers that list to me the next day with each bond described therein checked with his initials showing that he has exam received & examined approved and filed the bonds— I do not see what better arrangement can be made to guard against errors or frauds — and hope that none will occur in the future. Mr [Albert] Palmer’s misconduct was discovered rather accidentally by an examination of the contents of Mr Benjamin’s safe— In Benjamin’s check book was found memoranda of checks given to Mr. Palmer and a note from Palmer to Benjamin requesting his check for $150— It was also discovered by Mr. Hanscom that Palmer had signed as surety one of Benjamin’s bonds of $500 for a shipment of Goods to Nassau. These discoveries were made on the 7th while I was absent from the office for a few hours on Special duty official duty— The Naval Officer and Marshal & Mr Hanscom came to my office to report the facts and in my absence on the advice of Mr a Special Agent of the Treasury Department now here aiding me in investigations of the affairs & business of the Custom House with references to important suggestions & recommendations which will when approved by the Secretary be laid before the appropriate Committee of Congress— He advised they laid the evidence before the General [John] Dix who ordered Palmer’s arrest— I was absent from half past one till 4. O’clock — when I returned Palmer had been arrested & was on his way to Fort Lafayette— I was much surprised and shocked by the discoveries and the consequent arrest— His integrity had been twice assailed by prominent political gentlemen and the matters alledged against him had been thoroughly investigated by very competent autho officers of the Treasury Department and he was completely exh onerated in both instances — in the latter case his accuser himself gave a written statement to the investigating officer retracting the charges & expressing his entire satisfaction of his innocence— He was afterwards made a member of the State Union Committee & placed by them on the Executive Committee of that body in which I understand he served efficiently at during the last State Election canvass— I was opposed to his going on the State Committee and refused permission for him to go to the State Convention and requested him to deny the use of his name for the Committee— I thought it unwise to advance so young a man to such a position especially as he was in close relations to me— I understood that he did what he could to prevent it— But he was appointed & his acceptance urged so that I finally yielded my consent to his attending the meetings of the Committee in this City. His connection with public & political matters has brought him into notice to his injury — & he contracted expensive habits— These I suppose led him to seek money outside of his Salary; hence he was induced to assist Benjamin in getting sales factory bonds bondsmen to complete bonds which Mr Stanton accepted— I have no evidence of any other failure in his duties— I had confidence in him up to the time when I left the office on the day of his arrest. But I have since learned of some associations of his which would have impaired my confidence in him & caused his dismissal if I had learned them before. I am now engaged in investigations which will show, I am sure, whether other persons in or outside of the Custom House have had improper connections with this bond business and you may rest assured that the proper punishment so far as my power goes will be meted out to all guilty parties— I regret most deeply these disgraceful transactions and I am mortified that I should have reposed confidence in unworthy persons But is it possible to avoid some mistakes of this character so long as the government officers are filled in the manner they are & subject to political influences as they must be to a considerable extent-The Custom House I am assured by those acquainted with its business & history for 20 or 30 years was never so well officered and its business never so well conducted as it has been during your administration— Of course I am incompetent to make a comparison; but I know it is incomparably better than I found it— And I hope to improve it so as to make it confessedly a credit and not a reproach to your administration— I have never allowed articles complimentary to myself to go into the newspapers when I could prevent it — nor have I authorised any defence of attacks made upon me by them— Perhaps I have undervalued the importance of publishing what is done in the way of correcting evils that have come down through former administrations— I may hereafter give information on these matters to the daily press — and it may save to silence their clamor, and satisfy their desire to publish something about the Custom House, continually— It is better they should publish truth than falsehood. If I have erred in imposing confidence in an unworthy person I suppose I am not the only public officer who has made such a mistake If a chief officer is to be held responsible for the fidelity of his Subordinates who is safe in the assumption of such responsibility or who would risk a fair character & position in the community by taking office? I have written you a long letter — when I began I intended only to write a note which should assure you that I am not unmindful of all your kindness to me & of my duty to the Country and yourself …”3

Weed had policy reasons to back up his political grievances. Contraband was apparently flowing through the port with the connivance of Stanton and his son, Daniel. Secretary Chase launched an investigation — through Edward Jordan, the solicitor of the Treasury Department — which found that the procedures requiring bonds of importers were not being followed. The results of his report were published in the New York World and New York Times and became a major issue in New York in late 1863. According to historian John Niven: “As much as Chase deplored Stanton’s guilt and its damage to his own reputation, he was far more concerned that his share of the custom-house patronage was weakening under direct attack from Weed, who was presumably acting in Lincoln’s interest.

Chase wanted to maintain his control — in part as a base for his presidential aspirations. The Customs Collector, Hiram Barney, was nominally a Chase man but not a strong one. He was also charged with condoning corruption in his office so Chase sent an aide, John F. Bailey, to investigate and to shore up his position against the patronage ambitions of New York political boss Thurlow Weed. Chase biographer John Niven noted that “Chase also called on William Orton, the internal revenue collector in the city, and Rufus Andrews, the surveyor in the custom house, for support against Weed, who was mounting a major assault on the New York radicals and was winning the battle.” According to Niven: “Complicating Chase’s problem was recurring evidence of corruption and mismanagement in the custom house. Yet Chase remained sublimely confident, belittling the political problems that were thickening around him.”4 For example, in late February, 1864, New York businessman Moses H. Grinnell sent President Lincoln a long letter in which he laid the case against Barney and for his friend Simeon Draper.

I have already sent you a letter signed by several leading business men, in relation to the Collectorship of New York— I address you again because I wish to communicate to you some veiws [sic] on that subject which could not well be included in the former communication— I regret extremely that I cannot see you — I would have called upon you but am suffering from lameness which renders travelling impracticableIt is impossible to overestimate the importance of immediate action with regard to the Custom house in this City— While the personal integrity of the present Collector is not impugned, there is felt universal and intense dissatisfaction with his Administration of affairs — the Commercial portion of this Community are thoroughly persuaded that he is incompetent and incapable of managing the office — they demand a change —Mercantile men cannot understand why an office which requires of its incumbent such thorough & practical knowledge of the principles of trade and commerce and all their applications should be held by a lawyer — a man whose professional training habits of thought and business methods are not only different from but inconsistent with those of merchants — They may be wrong in their view of it but the leading business men are firmly convinced that no lawyer can adequately fill the position —The party which in this City has rendered to your administration and to you personally the most efficient support, composed as it is of men representing a large portion of the wealth of the Country feels entitled to some consideration at your hands in a matter which affects not only their personal feelings and interests but the character and repute of the Commercial Metropolis of the Nation — the present management of the Custom House in their judgment is discreditable in the extreme — they desire such a change as will hold out to them some reasonable prospect of a reform —An appointment which would place the patronage of the office under the control of men who are known to have regard for nothing but their own aggrandizement would not only be a bitter disappointment to your reliable friends but would probably induce many of them who have heretofore warmly supported you to consider themselves at liberty to withdraw from any further action on your behalf and perhaps to adopt entirely different views with regard to the future from those they have hitherto entertained-You may not be aware of the fact that none of the socalled “regular” organizations in the State took any action whatever with regard to your re[-]nomination until after the publication of the proceedings of the Association formed in this City by gentlemen not belonging to or in any way connected with these organizations — they were unwilling to commit themselves and refrained as long as possible — they now, at the very outset of the Campaign while ostensibly supporting you discourage all efforts in your behalf and demand a price for their exertions —So far as I am informed all official influences are working against you and if more power is placed in the hands of mere place hunters you can have no reliable assurance that it will not be used to your detriment—Mr Draper is the unanimous choice of the Merchants of this City for the Collectorship — they have confidence in his abilities and integrity — he will not have to have the duties of the office and no appointment that could possibly be made would secure to you a stronger or more effective support in this community—We all feel that he has legitimate claims upon the Administration although he has never been willing to press them — No man in this State gave more freely of his means or his personal exertions to bring it into power or sustain and strengthen it since—His labors and sacrifices have received neither acknowledgement or return and although it cannot be claimed that they entitle him to position they should certainly be fully considered when he is proposed for a place for which he is eminently fitted and in which he could render the most important and valuable service —I have not considered it necessary to make any reference to recommendations which have been or may be laid before you bearing the signatures of members of the Legislature — signatures obtained before it was known that a change in the Collectorship was contemplated— Such recommendations can be easily traced to the influences in which they originated-This matter affects mainly, if not exclusively the Mercantile interests of New York — the representatives of that those interests have not only not been consulted but they have been entirely excluded from consideration by the gentlemen who have obtained the legislative endorsements referred to which indeed would have been given to any respectable republican who asked for them-I have written thus frankly and earnestly because I desire that your real friends here, who are sincerely devoted to your interests, should be assured of your cooperation with them and not be exposed to the danger of defeat by means which you yourself will have placed in the hands of professed friends but real adversaries-5

Several weeks later, Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole visited New York and reported on the attitudes of Grinnell and others in a rambling letter to his governmental superior, Interior Secretary John Palmer Usher. Usher shared the letter with President Lincoln: “Last night I met at the Union Club Rooms some of the solid men of New York viz Mr Taylor Moses H Grinnell several of the Bank Presidents — and Bank cashiers — amongst them the Prest & Cashr of the Bank of Commerce Simeon Draper — &c &c They are unconditionaly [sic] for Mr Lincoln[.] But agreed in saying that all or nearly all of the patronage of the City was against them & for Sec Chase and that Mr Barney must go out or the City was Lost to us — all agree that Barney must go out & I believe that a majority perhaps a Large Majority agree that the present Post Master here should have the place — a few are for Mr Draper — he did not mention it to me[.] But the radicals & the Weed men agree in a great degree upon the Post Master — and as this is a compromise — I have no doubt that it is best. Wm A. Darling Prest of the 3d Ave R. R. and Late Lincoln Elector — called upon me with Mr Keifer Late recorder of this city— They agree that if the P. M. Mr Wakeman is at once put in the Collectors office that he can & will secure the City for Mr Lincoln and that without this it is at Least very doubtful— Of course all these sayings must be taken with some allowance[.] But it is clearly the opinion of the people here who want office that the way to get it is to be for Mr Chase and so soon & that idea is disapated [sic] these factions will be for Mr Lincoln and it may be that others than Mr Barney should go over I have been very careful in what I have said, think I have done good. The friends of Mr Lincoln thi[nk] so or say so at Least I have pointed out the dif[f]iculties in the way of the Prest doing all they ask & have I think convinced some of our friends that they are asking to much— all agree that Mr Lincoln can make no present change in his Cabinet or any promises for the future & yet they want to feel that it will be done— I have said to them that my understanding is that Mr Lincoln if reelected will be relieved of any embarrassment by the tender of resignations, by the principle office Holders at Washington & that he would of course reap[p]oint only such as should be satisfactory to himself & the country I know this is your view of what is proper & it is mine— 6

Grinnell ally Thurlow Weed was actively seeking a change. So was Weed’s political ally, New York Times Editor Henry J. Raymond. Raymond wrote President Lincoln in early March 1864: “If the Collectorship of this Port is to be vacated I beg leave to say that in my judgment Hon. A. Wakeman is the very best man for the succession. His ability, personal character, political experience, & general familiarity with the duties and responsibilities of such a position qualify him to fill it with complete success. His appointment, moreover, I think would contribute largely towards healing sundry domestic differences in the ranks of the Union party, and that too without any sacrifice of principle or any injustice to individuals.”7 Wakeman was then New York City’s postmaster. Eventually the weight of the Weed machine was placed behind businessman Simeon Draper as a replacement — but even that change had to wait until September 1864.

“The President [would] rather appoint Chase’s friends than to say no,” complained Senator Edwin D. Morgan to Thurlow Weed after Chase named John T. Hogeboom as Customs appraiser at large early in 1864.8 Hogeboom — along with Barney and George Opdyke — was part of the anti-Seward delegation of New York Republicans who had ventured to Springfield, Illinois in January 1861 to promote the interests of Salmon P. Chase. But Hogeboom’s major sin seemed to be that he was anti-Weed.

“I informed Mr. Lincoln, when I saw him in November, that the infamies of the Appraiser’s Office required the Removal of Hogeboom and Hunt, men whose appointments, originally, we in vain resisted….It is not alone that these men are against Mr. Lincoln, but they disgrace the office — a Department everywhere spoken of as a ‘Den of Thieves.’ Mr. Lincoln not only spurns his friends,” wrote Weed to Supreme Court Justice David Davis, “but Promotes an enemy who ought to be removed!”

Weed added: “After this outrage and insult I will cease to annoy him; and tho’ ever remembering how pleasant my acquaintance is with you, I will no more trouble with matters which make us both unhappy.”9

Several months later, President Lincoln wrote: “Much as I personally like Mr. Barney, it has been a great burden to me to retain him in his place, Barney, it has been a great burden to me to retain him in his place, when nearly all our friends in New-York, were directly or indirectly urging his removal. Then the appointment of Judge Hogeboom to be general Appraiser, brought me to and has ever since kept me at, the verge of open revolt.”10 New York was indeed in a perpetual state of patronage ferment which required Presidential attention. Willard L. King, biographer of Supreme Court Justice David Davis, wrote:

In January 1864, Lincoln asked Davis to send for his friend, Thurlow Weed. Ugly evidence of corruption, if not treason, in the New York Customs House was being aired in Congress; arms and contraband had escaped to the South by collusion of customs officers in New York. The President wished to consult Weed about a successor to Hiram Barney, the present Collector of Customs and Chase’s close friend. On his arrival in Washington, Weed declared that the change must be made but that he had no special candidate in mind for the post. Lincoln had already arranged to send Barney to Portugal as minister and thought he would appoint ex-Senator Preston King, a former Democrat but a good friend of Seward, as a Collector. Weed approved, but Chase, on hearing of the proposed change, threatened to resign if Barney were removed.”A month later, Weed wrote Davis that the Chase appointees in New York were blocking an endorsement of Lincoln in the New York legislature. When would the President remove Barney? Weed had heard that Lincoln now intended to appoint in Barney’s place Abram Wakeman, the Seward-Weed postmaster in New York. That appointment would be a good one, Weed admitted, but he asked to be informed if Wakeman were to be appointed. After his interview with the President, Weed had told Wakeman not to press his application because it would embarrass Lincoln“Responding to Weed’s letter, Davis asserted that Lincoln’s intention to remove Barney had never been abandoned, but the President was embarrassed by the many petitions for Wakeman’s appointment and could not act until he decided who should succeed. Davis believed that Preston King would be the man and thought that Lincoln would inform Davis before he acted, so that he could tell Weed.11

This agitations required presidential aide John G. Nicolay to make at least two trips to New York City in 1864 to try to pacify Weed and make changes in various posts. After meeting twice with Thurlow Weed on March 29 and 30, Nicolay wrote President Lincoln about the unhappiness of Weed and Senator Edwin D. Morgan:

Mr. Weed was here at the Astor House on my arrival last Saturday morning, and I gave him the note you sent him.He read it over, carefully once or twice and then said he did not quite understand it. He had written a letter to Judge [David] Davis which the Judge had probably shown you, but in that he had said nothing about Custom House matters.He said that all the solicitude he had was in your behalf. You had told him in January last that you thought you would make a change in the Collectorship here, but that thus far it had not been done. He had told you he himself had no personal preference as to the particular man who is to be his [the present Collector’s] successor. He did not think Mr. Barney a bad man but thought him a weak one. His four deputies are constantly intriguing against you. Andrews is doing the same. Changes are constantly being made among the subordinates in the Custom House, and men turned out, for no other reason than that they take active part in primary meetings &c. in behalf of your re-nomination.His only solicitude he said, was for yourself. He thought that if you were not strong enough to hold the Union men together through the next Presidential election, when it must necessarily undergo a great strain, the country was in the utmost danger of going to ruin.His desire was to strengthen you as much as possible, and that you should strengthen yourself. You were being weakened by the impression in the popular mind that you hold with ‘much tenacity to men once in office, although they prove themselves unworthy. This feeling among your friends also raises the question, as to whether, if re-elected, you would change your Cabinet. The present Cabinet is notoriously weak and inharmonious — no Cabinet at all — gives the President no support. Welles is a cipher, Bates a fogy, and Blair at best a dangerous friend.Something was needed to reassure the public mind and to strengthen yourself. Chase and Fremont, while they might not succeed in making themselves successful rivals, might yet form and lead dangerous factions. Chase was not formidable as a candidate in the field, but by the shrewd dodge of withdrawal is likely to turn up again with more strength than ever.He had received a letter from Judge Davis, in which the Judge wrote him that he had read his (Weed’s) letter to you, but that you did not seem ready to act in the appointment of a new Collector, and that he (the Judge) thought it was because of your apprehension that you would be merely getting out of ‘one muss into another.’A change in the Custom House was imperatively needed because one whose bureau in it had been engaged in treasonably aiding the rebellion.The ambition of his life had been, not to get office for himself, but to assist in putting good men in the right places. If he was good for anything, it was an outsider to give valuable suggestions to an administration that would give him its confidence. He feared he did not have your entire confidence — that you only regarded him with a certain degree of leniency…as being not quite so great a rascal as his enemies charged him with being.The above are substantially the points of quite a long conversation. This morning I had another interview with Mr. Weed.He had just received Governor Morgan’s letter informing him of the nomination of [Judge John] Hogeboom to fill McElrath’s place and seemed quite disheartened and disappointed. He said he did not know what to say. He had assured your friends here that when in your own good time you became ready to make changes, the new appointments would be from among your friends; but that this promotion of one of your most active and malignant enemies left him quite powerless. He had not yet told any one, but knew it would be received with general indignation, &c &c.12

Nicolay stayed in New York for a few more days. He wrote his fiancé, Therena Bates, on April 1: “I have been mainly occupied with seeing and talking with politicians in regard to the next Presidential election, about which there seems to be more diversity of views and interests here than anywhere else in the country, although the general fact that Lincoln’s re-nomination and re-election is considered almost a foregone conclusion even by those who are dissatisfied with that result and who therefore adopt the belief very reluctantly and unwillingly….”13

The controversy over Barney lingered for months. Chase biographer Albert Bushnell Hart wrote: “An unusual self-abnegation on Chase’s part might have prevented a rupture, but that self-abnegation he did not show, for even after the nomination he felt injured and sore. Another cloud now arose in the New York Custom House. On June 6, the President called on Chase, and pressed for the removal of Barney, to whom he had previously offered a diplomatic position. This personal conference removed the difficulty for the time being; there is some reason to suppose that Chase again threatened to resign, and that the President again gave way.”14

When John Cisco resigned as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for New York, the President determined that the political wishes of Senator Morgan and his moderate Republican allies should be satisfied. Ironically, it was they who most objected to Chase’s habit of appointing Democrats like Cisco and Hogeboom. “Secretary Chase was determined that his supporter, Maunsell B. Field, should be appointed by Lincoln as Assistant Treasurer in the metropolis,” wrote historian Reinhard H. Luthin. “But the President, striving for party harmony to preserve the Union and strengthen his own chances for re-election, wanted no man who would be obnoxious to the Seward-Weed wing of the party in New York State. Too, Lincoln always was a firm advocate of what later became known as ‘Senatorial courtesy’ in the matter of appointments. He consulted with the two United States Senators from New York, Senators Morgan (affiliated with the Seward-Weed group) and Ira Harris. Morgan found Chase’s man, Field, personally obnoxious, and advised Lincoln against the appointment.”15

Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote that Maunsell “Field was endorsed by some of the most honorable business men of the metropolis, including Jonathan Sturgis, Peter Cooper, Phelps, Dodge and Company, as well as by ex-Governor John A. King, Greeley, and others; and he had been recommended by Cisco, under whom he had formerly served before becoming assistant secretary of the treasury. On the other hand, there is some evidence that Field, despite his talents, was not a suitable man for the office.”16

Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “Lincoln was rather astonished…when word came that Chase had fixed upon a gentleman by the name of Maunsell B. Field as his choice for the vacancy. That Mr. Field was Democrat, probably a radical, since Chase had selected him, was known, but these qualities had little importance in this case, for he was a man without political influence or following of any kind, and indeed, with no known interests or achievements in public life. For less than a year, he had been serving as Third Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, a position that Chase had created for his particular benefit; but his relation to Chase had a rather a personal than an official character. He was a man of ingratiating presence, good education, polished manners, and of some slight ability as a writer, but he had never figured in public life, even in a minor degree.”17

President Lincoln rejected Chase’s attempt to place the socially connected but professionally inept Maunsell B. Field in Cisco’s place: “Yours inclosing a blank nomination for Maunsell B. Field to be Assistant Treasurer at New-York was received yesterday. I can not, without much embarrassment, make this appointment, principally because of Senator Morgan’s very firm opposition to it. Senator Harris has not spoken to me on the subject, though I understand he is not averse to the appointment of Mr. Field; nor yet to any one of the three named by Senator Morgan, rather preferring, of them, however, Mr. Hillhouse. Gov Morgan tells me he has mentioned the three names to you, towit, R. M. Blatchford, Dudley S. Gregory, and Thomas Hillhouse. It will really oblige me if you will make choice among these three, or any other man that Senators Morgan and Harris will be satisfied with, and send me a nomination for him. 18

“The strifes and jars in the Republican Party at this time disturbed him more than anything else, but he avoided taking sides with any of the faction[s], with the dexterity that comes of simple honesty, which always finds the right road because it is looking for nothing else. I asked him why he did not take some pronounced position in one trying encounter between two very prominent Republicans,” said New York Secretary of State Chauncey Depew. The President Lincoln replied: “I learned a great many years ago, that in a fight between man and wife, a third party should never get between the woman’s skillet and the man’s ax-helve.”19

Much of the turmoil focused on the New York Customs office of the Treasury Department. “This dark granite building on Wall Street, between William and Hanover Streets, had long been the subject of intermittent breast-beatings decrying the graft and inefficiency surrounding it, and of course most of the charges were true,” wrote Roscoe Conkling biographer David M. Jordan. “The New York Custom House collected more revenue than all the other ports of entry to the United States combined, and its presiding officer, the collector, received under the unique system of compensation in effect, based largely on shares called ‘moieties’ of collected fines, a much larger annual income than his superior, the secretary of the treasury, larger even than that of the president.”20

Chase and his supporters were blamed for much of the discord, but he apparently paid some attention to local sentiment for Senator Ira Harris wrote President Lincoln in August 1862: “I have seen the list of appointments under the tax law prepared by the Secretary of the Treasury for the State of New York — They are with one or two exceptions entirely satisfactory.”21 But the Treasury appointments in New York City increasingly became a political battleground. Typical of the complaints was an August 1864 letter from Republican State Treasurer James Kelly, which Seward showed President Lincoln:

Chase availed himself of this fact and in place of awarding to you the patronage of your own State, (the only State that went solid for her candidate at Chicago) he grasped the whole patronage of the Country, and in this State he has brought out some or most of the dead political beats we had, men who had no claim to the positions they received and who were inadequate to the duties. Men received appointments who could not for want of experience and knowledge select the true men or those having capacity as well as political integrity, men whose claims were set aside or repudiated until many of our best men got disgusted and left them to run their race.Take our Custom House with Hiram Barney. I was on our Central Committee with him three years where I never knew him to offer a suggestion, support or oppose a resolution, in fact all must admit that he is a perfect negative man and possesses no knowledge of politics in any shape and makes no pretentions to such knowledge. When first appointed he stated it was war times and men should not be removed for their political opinions with such balderdash, yet we were constantly hearing of entire strangers receiving lucrative situations under the Collector, this man should be sent abroad for his Countrys good.Barney left the political working of the Custom House to R[ufus] F Andrews who was a political adventurer from the start, acting at one time with Americans at another with Whigs or Republicans or with any from whom he could get a nomination, he has been the bane to our success since he has been Surveyor acting in running opposition to the regular nominations of the party, at one time under the cognomen of the Peoples or Citizens party and at this time claiming to be running a Union party, which at one time meets at some rum shop again at Hope Chapel or the Medical Academy. at one time it is the Tucker Committee and then the Chas H Marshall Committee, and this man Andrews is suffered to remain and damage the Administration.Can it be possible that the President cannot open his eyes to the injury this sycophantic Andrews is doing the party. I have the kindest feeling towards Barney as I know him to be a gentleman and I am a member of a Loyal League Club with him and meet him frequently but consider him of no account politically,22

Shortly after Kelly wrote this letter in August. Nicolay returned to New York and again sought meetings with top Republicans with the purpose of making key patronage changes. It was at a time of political turmoil for President Lincoln — when dissident New York City editors, some previously aligned with Chase, sought a change in the Republican ticket. Nicolay wrote President Lincoln on August 29:

I have seen no one yet but Mr. Raymond and Mr. Weed, and several influential men from the country, who were in Mr. Raymond’s office when I went there.Raymond is still of opinion that the change contemplated should be made at once, although he does not seem to have conferred with any one, except Weed, who joins him very decidedly in the same belief. I myself asked Mr. Weed the distinct question whether the change ought to be made now, or after the election, and he answered, now by all means.23

Republican National Chairman Henry J. Raymond himself had recently been in Washington to confer with the President about problems he foresaw with his candidacy. He wrote President Lincoln on August 30 to promote change — but to try to avoid a change which would install former Republican State Chairman Simeon Draper in the Collector’s job:

You asked me to write you after a day or two & to give you my impressions as to the wisdom of carrying into effect the changes you propose to make in our City officers, just now. Every person with whom I have conversed has been positive in saying that a change was absolutely necessary, & that the sooner it was made the better. As things now stand we get no strength from the Custom House. A change in the heads will stimulate every person in office to earn retention, — & excite in everybody outside the hope of earning an appointment. Of course it should be understood that there is to be no sweeping change of subordinates before the election.Some little embarassment [sic] has been caused by the indiscreet revelation to Mr. [Simeon] Draper of the change intended. He insists on being Collector — and is or course resolute against having anything less. I cannot think it would be wise in any aspect of the case to make him Collector and I feel sure that when he finds that hopeless, he will consider half a loaf a good deal better than no bread. At all events he will have no ground for complaint.On the whole I see nothing better than the programme you originally laid down, and I am of opinion that the sooner it is done the better. And it seems, furthermore, indispensable that something should be done at once.24

Nicolay continued his meetings with Raymond, Weed, Senator Morgan, attorney William Evarts and others. Nicolay wrote President Lincoln on August 30 that U.S. Attorney “Delafield Smith, and Mr. Evarts also concur with Weed. Gov. Morgan was here at the Astor House a little while this evening. I talked with him on the subject, and while he seemed to have no definite impressions as to what really was best to be done, he said he would stand by whatever you might do. I saw Greeley yesterday and today; I did not talk very fully with him on this matter but gathered from what he said, that while he did not see much good likely to result from changes, yet that Barney was not good for anything.”

On the whole I have concluded that I will endeavor to see Barney and Andrews as early as I can tomorrow, if they are in the City, and ask them for their resignations in accordance with your instructions.“Almost all those with whom I have consulted, however, unite in saying that, excepting the Collector and Surveyor, there should be very few, if any other changes in their subordinates. Those who are in should have the hope other changes in their subordinates. Those who are in should have the hope of being kept in as a motive for work, while those who are out should have the hope of being put in to prompt them. The new appointees of Collector and Surveyor should receive instructions from yourself on this point.“Mr. [William] Everts [sic] is very earnest that Draper should be made collector instead of Wakeman.Gov. [Edwin D.] Morgan and Senator Morrill have been through most of the New England States. They report an improved state of feeling in all respects, and say we will certainly [carry] Maine at the approaching September election, by a good majority.“In my conversation with Mr. Greeley I urged upon him the necessity of fighting in good earnest in this campaign. He said in reply ‘I shall fight like a savage in this campaign. I hate McClellan.’Mr. Weed and Gov Morgan concur in the opinion that Preston King will not take the Post Office in this city. Gov. Morgan suggests James Kelley instead.“I send this by Robert [Todd Lincoln]. If I get matters arranged satisfactorily I may start home tomorrow night — if not I will stay another day unless you telegraph for me.25

On August 31, Nicolay met with Barney, who sent his resignation to Secretary of the Treasury William Pitt Fessenden almost immediately. Nicolay wrote President Lincoln that Barney “at length acquiesced very cheerfully, saying that he should still do all he could for you and the cause, and should retain all his personal friendship and esteem for you.” Andrews was a harder case and protested the “personal ill-will” of Weed but later sent in his resignation as well.26

But President Lincoln was also subject to many conflicting pressures. For example, Senator Ira Harris telegraphed him on September 1: “I think it would be exceedingly unwise to remove Surveyor Andrews at this time.”27 General Daniel Sickles, a War Democrat, wrote President Lincoln from New York on the same subject on the same day: “I observe in the papers that you are said to contemplate a change in the Surveyors office— Unless there are imperative reasons for the removal of Andrews I am satisfied upon general grounds it would be inexpedient — he has a strong hold upon the political organization with which he is identified — has many devoted personal adherents of no mean influence and can be more useful to you probably than any new man entering office so near the election. The intimate professional and personal relations which have long existed between Andrews and myself and the disinterested and constant friendship he has manifested, give me the strongest solicitude for his reputation and welfare, and I shall ever regard it as a very marked personal kindness to myself if you will allow Mr Andrews to continue in his position — a course which I am sure will also prove to be most advantageous to your own interest, all things considered.”28 Ironically, Sickles did not in this letter promote the interests of Abram Wakeman — who had recently written President Lincoln suggested that Sickles was “idle”, politically “popular” and should be given a new command. He wrote: “Hancock & [Joseph] Hooker are really great generals, but in this business, in this State, Sickles would surpass either of them”.29

A different complaint came from New York businessman Moses H. Grinnell, an influential Republican leader. He wanted to make sure that Draper got the Collector’s post — as indeed he eventually did: “The proposal to make Mr. Wakeman Collector does not meet with the popular wish, He holds a good Office, our party has fallen to a mere cypher, while he has held the position of representing the Administration and certainly nothing can warrant one man holding two prominent offices, and placing such a man as Mr Draper Subordinate to him. Mr Drapers friends…unite as one man in approving of his decision which is to decline the office of Surveyor, The Collectorship is due to him and his friends, and it is the best political disposition of the office.”30

But Wakeman had supporters. Union League Vice President C.W. Goddard wrote: “It is said here to day, that Mr Draper, demands to be Collector, instead of Wakeman— This I regret much, for it may be embarrassing, yet I hope not — It is well understood throughout the State, if a change takes place, Wakeman, is to succeed Barney & the disappointment will be great, if it is otherwise— ” He invoked the influence of the President’s supporters in the Union League: “As a League, we have never but once lent our power for the purposes of assisting any one to office but the necessity for this change seemed so great that our Executive did endorse Mr Wakeman, believing him to be the best man in the State, everything considered, for the place, & especially now when so much is to be done, pray do not disappoint us— We do not want him Surveyor, where he can have no power, we want him Collector, where he can render us, the material, aid it would then, be in his power to give the Cause— It would be letting him down from where he is now, to give him the position of Surveyor, for now he has 400 men, under his controll [sic], but there he would have comparatively few— I repeat again what I said to you the other day, that if Wakeman was Collector, it would make several thousand votes, in our favor, the coming Canvass, & we may, need them”.31

President Lincoln embarked on phase two of his political pacification program in New York when he arranged the dismissal of the radical Collector of the Port of New York, Hiram Barney, and his replacement with the more moderate Simeon Draper, an ally of Thurlow Weed and his political friends.

John G. Nicolay was President Lincoln designated envoy to arrange for resignations and replacements. Draper got the Collectorship but Wakeman was named Surveyor. James Kelly got Wakeman’s old job as Postmaster.

John G. Nicolay was President Lincoln designated envoy to arrange for resignations and replacements. Draper got the Collectorship but Wakeman was named Surveyor. James Kelly got Wakeman’s old job as Postmaster.

Raymond was right about one observation. Changing two top jobs shook the Republican organization into action. Historians Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin wrote that in the wake of the dismissal of Barney and Andrews: “There were, indeed, some removals of deputy collectors, weighers, inspectors, and debenture officers immediately upon the appointment of Draper. These few dismissals seem to have been sufficient to bring all into line. ‘It is remarkable to note,’ one New York reporter observed, ‘the change which has taken place in the political sentiments of some of these gentlemen with the last forty-eight hours — in fact, an anti-Lincoln man could not be found in any of the departments yesterday.”32 The historians wrote “The appointment of Draper as collector, Wakeman as surveyor, and Kelly as postmaster of New York City indicated that Lincoln fully realized that the Seward-Weed faction of Republicans must be awarded more recognition if the Empire State was to be made sure for Lincoln in November.”33 Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “Draper, Wakeman and Kelly were all good Weed men; and thus this important patronage, which Weed and his followers and so long coveted, was at last captured from his adversaries.”34

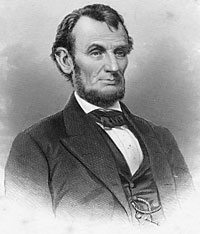

It was a nasty and brutish campaign, though blessedly short as a result of the Democrats’ late convention. President “Lincoln was using the patronage to build the Republicans into a national party with himself at its head. Lincoln kept control of the patronage, subjecting himself to the ordeal of listening to office-seekers and doling out the appointments,” wrote William B. Hesseltine. “And even when he did not personally take the responsibility, he set the policy. The policy was national. He consulted congressmen on appointments in their districts — even on commissioners in the army.”35

One reason that Republicans wanted to control the patronage — was that they could control fund-raising from the patronage appointees. Historian Allan Nevins wrote : “In raising money for speakers, pamphlets, and a thousand other purposes, the Republicans fell back upon the well-established process of assessing Federal officeholders for contributions. With some exertion Raymond obtained the assistance of the War Department, Treasury, and Post Office, but the Navy under the stern moralist Gideon Welles remained impregnable. Regarding Raymond as a journalistic mercenary, Welles was disgusted by his attempt to use navy yards to elect candidates instead of build ships. He stigmatized the collectors of assessments as harpies who put into their own pockets much of the money they extorted. Nevertheless, Raymond finally succeeded in getting the Brooklyn navy yard to dismiss men because they supported McClellan. He collected money so brazenly in the New York Post Office and (after Hiram Barney left) the Custom House, that the Herald and Worldemitted indignant growls. When Phelps, Dodge, the metal dealers gave him $3000, and he tightened the screws on other contractors, the World snorted that every man who sold the government a pound of pork or bottle of quinine was expected to walk into the National Committee offices and plank down his greenbacks.”36

Nevins wrote: “Welles was the only cabinet member who objected to the general levy upon officeholders, five percent being the accepted amount. A committee under Senator James Harlan of Iowa looked after this shabby screw-tightening. Montgomery Blair had given $500 to the campaign fund, and when workers in the New York post office objected to paying tribute, his successor William Dennison told them he thought the levy was right. Lincoln had a hard-headed sense of the importance of parties and elections, but also a hard-headed conviction that party demands must not pervert the standards of honesty and efficiency in government. He took no position on assessments except to refuse to permit coercive pressures on officeholders.”37

Although Lincoln remained publicly above the campaign, the Republican Party which had nearly dissolved in consternation and trepidation in August, solidified into a strong and effective campaign organization in the fall under the leadership of Henry Raymond. He squeezed political appointees for political contributions under the aegis of Sen. James Harlan. The President tacitly approved the operation although he was careful to oppose it when the screws were tightened too tightly or too obviously as they were at the Philadelphia Post Office. Historian James G. Randall wrote: “The fund-raisers did not confine themselves to Federal employees but also turned to individuals and firms doing business with the government. Raymond sent out a circular appealing to war contractors, and from one of them alone — Phelps, Dodge and Company, New York dealers in metals — he received at least $3,000.”38

After the chaos that afflicted the New York Republican Party in August, September proved to be a welcome change to organization and direction. On September 27, wrote historian James G. Randall, “at the Cooper Institute in New York, the Federal officials in that city turned almost en masse, ‘according to the New York World, which listened the names of many of them. And, according to the Indianapolis Daily State Sentinel, a hundred government clerks were kept busy in congressional committee rooms with mailing out Lincoln propaganda. They ‘continue to draw their salaries while engaged in re-electing Abraham Lincoln. They neglect the business of the country, for which only they ought to be paid.'”39

One of the biggest patronage positions opened during the campaign — when Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died. Most Republicans rallied behind former Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase. Weed tried one last major patronage effort. When Chief Justice Roger B. Taney died in October 1864, Weed promoted the candidacy of attorney William M. Evarts, whom he had backed for the U.S. Senate in 1861. Evarts himself wanted the post. “The Chief Justiceship is, it seems to me, for the next two years a place of great political importance over and above its simple judicial authority,” Evarts wrote a friend. “A good deal of interest has been spontaneously shown here to me in the place on public grounds, by persons of highest political influence….Aside from Gov. Chase I am justified in thinking that many things concur to make me a very prominent, if not the most prominent candidate.”40

But Evarts deceived himself. He was without national prominence or a personal relationship with President Lincoln. Many other potential candidates — such as former Postmaster General Montgomery Blair or former Senator Orville H. Browning — had greater claim on the President’s patronage. Although Evarts had support among judges in both New York and Washington, he lacked broad-based political support. Ultimately, President Lincoln chose former Treasury Secretary Chase.

“Had Lincoln led a united party he might have utilized his time and effort somewhat different,” wrote historians Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin. “His wise use of the patronage in holding the party together was a necessary antecedent to the formulation of any statesmanlike policy concerning the nation. Many Lincoln admirers find it distasteful — perhaps unbelievable — to recognize in their hero the shrewd practical politician that he was. But to witness how, as a politician, he utilized the patronage in holding together diverse conflicting factions in common purposes — the preservation of the Union, the success of his administration, and the rewarding of the party faithful — is only to enhance the greatness of Lincoln. Essentially a practical man, reared in the realism of the frontier and educated in the old school of Whig politics, Lincoln recognized the necessity of patronage as a weapon in party leadership under the American system. In being a competent politician, he became a statesman. Had he not displayed his ability as a politician with such signal success, it is doubtful whether he would be regarded today as a statesman. Had he not wielded the patronage so skillfully — something that his predecessor James Buchanan and his successor Andrew Johnson did not do — probably his administration would not have been successful. Certainly his task of holding the Union together would have been more difficult.”41

Footnotes

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Hiram Barney to Abraham Lincoln, January 9, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Moses H. Grinnell to Abraham Lincoln, February 23, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William P. Dole to John P. Usher, February 20, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry J. Raymond to Abraham Lincoln, March 10, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 413 (Letter to Salmon P. Chase, June 28, 1864).

- Willard L. King, Lincoln’s Manager: David Davis, p. 214 (Letter from Thurlow Weed to David Davis, February 9, 1864 and letter from David Davis to Thurlow Weed, February 12, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 132-133 (Letter to President Lincoln, March 30, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 132-133 (Letter to Therena Bates, April 1, 1864).

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon Portland Chase, p. 315.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 517.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 392.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 444-445.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 412-413 (Letter to Salmon P. Chase, June 28, 1864).

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 448-449 (Chauncey M. Depew).

- David M. Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice of the Senate, p. 93.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Ira Harris to Abraham Lincoln, September, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James Kelly to William H. Seward, August, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 154 (Letter to President Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry J. Raymond to Abraham Lincoln, August 30, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 155 (Letter to President Lincoln, August 30, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 156 (Letter to President Lincoln, August 31, 1864).

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 262-263.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 351.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 345.

- Ernest A. McKay, The Civil War and New York City, p. 237.

- Willard L. King, David Davis, p. 216-217 (Letter from Thurlow Weed to David Davis, March 29, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Ira Harris to Abraham Lincoln, September 1, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Daniel E. Sickles to Abraham Lincoln, September 1, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abram Wakeman to Abraham Lincoln, August 12, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Moses H. Grinnell to Abraham Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from C. W. Godard to Abraham Lincoln, August 31, 1864).

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 280 (New York Herald, September 7, 1864).

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 280-281.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, .

- James A. Rawley, editor, Lincoln and Civil War Politics, (From William B. Hesseltine, “Abraham Lincoln and the Politicians, Civil War History, Volume VI, March 1960).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 110.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory 1864-1865, p. 110-111.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 252.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 250.

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 316 (Letter from William M. Evarts to Richard Henry Dana).

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 336.

Visit

Hiram Barney

James Gordon Bennett

Simeon Draper

Reuben E. Fenton

Ira Harris

George G. Hoskins

Preston King

Edwin D. Morgan

Edwin D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George Opdyke

Abram Wakeman

Thurlow Weed

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)