George Templeton Strong was a conservative, establishment voice and force in New York City affairs. As a disciplined diarist, Strong’s voice are a window into Washington and New York politics and policies. He had little patience for those who did not share his priorities or act quickly enough achieve them. His “reactions to events illustrate the ebb and flow of confidence in the Union and its leaders. Strong, a wealthy New York City attorney and a member of numerous elite groups that supported the war, is perhaps the northern equivalent of South Carolina’s Mary Chesnut: quotable, opinionated, and a careful follower of events,” wrote historian Paula Baker. “He never trusted Lincoln’s competence, and he lost patience as his doubts deepened in 1862 after the second battle of Bull Run; Lincoln did not measure up to the job, and his only notable trait in Strong’s view was his ‘fertility of smutty stories.'”1

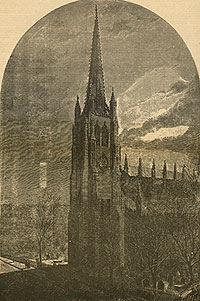

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that “it is evident that during the war few men in the country toiled harder than Strong, or with less thought of reward. Financier and lawyer in one, he kept his accounts with meticulous care.” He noted that “an all too typical day, Monday, February 6, 1864, found him working a long morning at his law office; seizing a hasty lunch; attending a meeting of the library committee of the Columbia trustees; catching a street car to 823 Broadway for a Sanitary Commission session; eating a quick supper; and then hurrying off to the Trinity vestry.”2

Strong was immediately caught up in the martial spirit and charitable causes of the Civil War. He became dedicated to the work of the United States Sanitary Commission. He wrote in August 1862: “Busy days. Sanitary Commission work, of course. Everything else is thrown overboard to my loss and damage. But I believe we are doing a considerable amount of service to the country and that we have saved more men than have been lost in any two days’ fighting since the war began. Thank God that a miserable, nearsighted cockney like myself can take part in any work that strengthens and helps on the national cause.”3

Strong’s energy was matched by that of his wife, Ellen Ruggles Strong, lobbying in Washington and serving as a chief nurse aboard Sanitary Commission hospital ships operating off the Southern coast. At one point during the Peninsula Campaign in July 1861, Strong wrote: “She writes in the best of spirits, undisturbed by all the rumpus and hurry about her, and thinking mainly of her work. She is a very great little woman!”4

The well-connected lawyer acted with a refreshing sense of modesty. “Fruitfully as he labored for Columbia [College], for Trinity [Church], for the Society Library, for the Philharmonic, and for the Sanitary Commission, he took care that only small groups of insiders should know how much he did,” wrote Nevins, who edited Strong’s diaries. “He was happiest withdrawn from the public gaze, living with his books, his music, his family, his religion, and his own rich nature. He sought only his own approval. As the diary shows, he had an almost morbid tendency to worry, a trait that he seems to have inherited from his father; and his worry sometimes produced severe fits of melancholia.”5

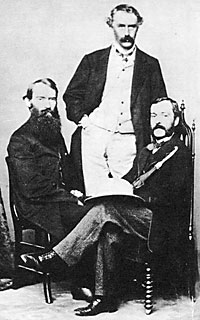

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Strong was a 41-year-old Columbia College graduate and attorney, specializing in real estate and probate law — in a firm that his father had founded. Historian James McPherson wrote that his “diary reflected the pulse of public opinion.”6 Historian Allan Nevins, who edited the published Strong’s diary, wrote: “His standards were exact, his sense of duty was high, and his punctiliousness was unfaltering. It would be hard to find an unfair note in the whole diary.”7

A few days after the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Strong wrote his diary: “Broadway packed full as I walked downtown and up again. The Sixty-ninth and Eighth Regiments marched down at about four. The former is the Irish regiment, Colonel Corcoran’s, and there were a large infusion of Biddies in the crowd ‘sobbing and sighing.’ Both regiments look as well as one has a right to expect of levies raised on such short notice. A large portion in citizen’s dress and without arms, but seemingly respectable material. The uniformed companies looked and marched well. At the corner of Rector Street and Broadway, I saw part of another regiment (I forget its number) raised by that notable aldermanic bully, Bill Wilson. They didn’t clearly know what regiment they were told they belonged to, but said they were ‘Billy Wilson’s crowd.’ A desperate-looking set. It’s said that when they were told they were to have not only the regulation arms but revolvers and bowie knives, too, they danced and yelled with delight: ‘We can fix that Baltimore crowd! Let ’em bring along their pavin’ stones; we boys is sociable with pavin’ stones!'”8

Strong’s focus soon shifted from military causes to charitable ones. After his appointment to the Sanitary Commission was announced in the New York World on June 14, Strong wrote in his diary that “I have heard nothing of my appointment from any other quarter, and never dreamed of any such thing. I can hardly believe this. So many scores of men are better qualified and more conspicuously fitted for the place and more likely to be thought of.”9 According to Nevins, “Some experienced officers, seeing the lack of sanitary facilities in most of the camps, predicted that fifty per cent of the volunteers would be killed or incapacitated by disease before the end of the summer.”10 11

Strong frequently visited Washington on Sanitary Commission business. He wrote of a meeting in May 1864 with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton: “I was amazed by the discovery of our importance and that the Secretary of War keeps himself thoroughly posted as to our movements and our doings. Whenever he referred to any publication, he rang in his messenger, and said, ‘Ben! Get me so and so of the Sanitary Commission,’ which the faithful but seedy creature did with admirable accuracy and promptitude.” Strong continued, “On the whole this interview was a good thing, though without direct tangible results. We drew Stanton’s fire and can estimate the weight of the metal. It is not very heavy. He hates us cordially and would destroy us if he dared, but he fears our constituency. Public favor is the breath of his nostrils. He is not a first-rate man morally or intellectually.” Strong also reported: “Pending our conference, the long, lean, lank figure of Uncle Abraham suddenly appeared at the door. Agnew and I rose, Stanton didn’t. Lincoln uttered no word, but beckoned to Stanton in a ghostly manner with one sepulchral forefinger, and they disappeared together for a few minutes, going into a side room and locking the door behind them. We saw Abe Lincoln in the telegraph room as we entered the office, waiting for despatches, and no doubt, sickening with anxiety — poor old codger! But it’s shameful so to designate a man who has so well filled so great a place during times so trying.”12

In addition to his work in New York and Washington, Strong also visited military facilities. He reported in his diary in mid-October 1863: “”Visited the convalescent camp near Alexandria Thursday afternoon. A lovely drive. From beneath the ruins of the old Virginny civilization, as manifested in desolate old houses and barns stripped of half their wood for fuel and shantybuilding, the germs of the New Order are springing up. There are ‘government farms’ nicely fenced and worked by gangs of contrabands, good roads newly cut, substantial bridges, and other.”13

Strong’s opinion of President Lincoln ebbed and flowed. By September 13, 1862 Strong voiced his disillusion with the Lincoln Administration: “Disgust with our present government is certainly universal. Even Lincoln himself has gone down at last, like all our popular idols of the last eighteen months. This honest old codger was the last to fall, but he has fallen. Nobody believes in him any more. I do not, though I still maintain him. I cannot bear to admit the country has no man to believe in, and that honest Abe Lincoln is not the style of goods we want just now. But it is impossible to resist the conviction that he is unequal to his place.”14 Strong wrote in his diary in 1862 that “we have been and are in a depressed, dismal, asthenic state of anxiety and irritability…permeated by disgust, saturated with gloomy thinking. I find it hard to maintain my lively faith in the triumph of the nation and the law….We begin to lose faith in Uncle Abe.”15

Strong went to Washington on April 18, 1865 to attend President Lincoln’s funeral with fellow commission members — Henry Bellows and Louisa Schuyler. “We entered Washington on time, for a wonder. Everywhere like insignia of sorrow. I got a breezy room high up among the higher ranges of Willard’s by special favor, for the city is very full. Sanitary Commission met in F Street at eight P.M. Jenkins was plainly unhappy, nervous, and unstrung; he had no quarterly report. He had tried to write his report, but had been in a state mental torpor that made it impossible. Three ladies attended our session. Miss [Louisa] Schuyler and Miss [Catherine] Nash of New York, and Miss Abby May of Boston.”16 The next day, commission members went to the Treasury Department where they met up with member of the U.S. Christian Commission. “They were an ugly-looking set, most of the Maw-worm and Chadband type. Some were unctuous to behold, and others vinegary, a bad lot. A little before twelve we marched to the White House through the grounds that separate it from the Treasury, were shewn into the East Room and took our appointed placed on the raised steps that occupied three of its sides — the catafalque with its black canopy and open coffin occupying the centre. I had a last glimpse of the honest face of our great and good President as we passed by. It was darker than in life, otherwise little changed. Personages and delegations were severally marshalled to their places quietly and in good order; the diplomatic corps in fullest glory of buttons and gold lace; Johnson and the Cabinet, Chief Justice [Salmon P.] Chase, many senators and notables, generals and admirals, [Ulysses S.] Grant, [David] Farragut, [Ambrose] Burnside (in plain clothes), [Charles H.] Davis, [David Dixon] Porter, [Louis] Goldsbourgh, and others. About 650 in all.” That was the highlight for Strong, who found the service itself “vile and vulgar.”17 As usual, things were not up to Strong’s high standards.

Footnotes

- Milton M. Klein, editor, The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 429 (Paula Baker, “New York during the Civil War and Reconstruction”).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. xl.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 244-246 (August 16, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 236 (July 1, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. xliii.

- James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam, p. 49.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. xliii.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 132 (April 23, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 159 (June 14, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 131.

- Duane Schultz, The Most Glorious Fourth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg, July 4th, 1863, p. 380-381.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 442 (May 8, 1864).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 362 (October 11, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 256.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, .

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 589 (April 18, 1864).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 589 (April 19, 1865).