Mary Todd Lincoln

Broadway, New York: South from the Park

Central-Park, Winter: The Skating Pond

Fifth Avenue Hotel

Fifth Avenue, 1859

Elizabeth Todd Grimsley

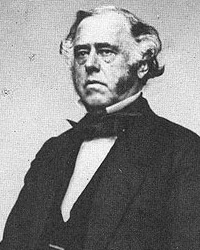

Benjamin Baker French

Elixabeth Keckley

Mary Todd Lincoln’s shopping trip to New York City in December 1860 was her second visit to the city. It was “her first excursion as a public figure with her own entourage,” wrote biographer Jennifer Fleischner. “The to-do made over Mary Lincoln by solicitous merchants, who were quite happy to extend credit to the future Mrs. President, was an undeniably thrilling experience, and Mary did not hang back from picking out whatever she wanted. But even better was the fawning welcome of the city’s leading citizens: powerful, wealthy, and sophisticated New Yorkers.”1

“Mary repeatedly made trips to New York and Philadelphia to order damask, wallpaper, carpets and curtain materials, most of which were brought over from Europe,” wrote Mary’s biographer, Ishbel Ross.2 By 1864, the bills for Mrs. Lincoln’s shopping trips, now more personal, were catching up with her and she was frightened. She complained to her black seamstress that if her husband were defeated for reelection, “I do not know what would become of us all. To me, to him, there is more at stake in this election that he dreams of.”3

Historian Margaret Leech wrote of Mary Todd Lincoln that “like a drug for her tortured nerves, she indulged in her orgies of buying things. She hoarded her old possessions in innumerable trunks and boxes, keeping even outmoded dresses and bonnets she had brought from Springfield. The charge accounts for her purchases mounted to appalling sums — things she could never use, for which she could never hope to pay. A Washington merchant sent in a bill for three hundred pairs of gloves ordered in four months. At A. T. Stewart’s New York department store, she bought furs, silks laces, jewelry, three thousand dollars for earrings and a pin; five thousand for a shawl.”4 Biographer Fleischner wrote: “If Mary had a psychological need to accumulate things to try to replace lost human love objects, her acquisitiveness was also cultural. Her childhood town and all her neighbors were simply steeped in commercialism; it was one of the reasons Mary loved New York, a giddily commercial city.”5

Although her shopping sprees drew criticism for their appropriateness during wartime, the New York Herald came to her defense, reporting that Mrs. Lincoln “came to the metropolis, visited the most modish stores, and — like the Empress Eugénie, who was as suddenly elevated in rank — displayed such exquisite taste in the selection of the materials she desired, and of the fashion of their make that all the fashionable ladies of New York were astir with wonder and surprise.”6

Not all of the criticism of Mrs. Lincoln’s shopping during the first year was warranted, according to another biographer, Jean Painter Randall. “Like flashes on a screen are the frequent newspapers items about her shopping trips to Philadelphia and New York that first year. The reporters sometimes showed excess of zeal. Mrs. [Elizabeth] Grimsley told of a pleasure trip to New York which she and Mrs. Lincoln made in May in which they ‘had not even driven by the stores.’ To their amazement after their return they read in the papers that they had been ‘on an extensive shopping trip with the names of the various stories visited, that ‘Mrs. Lincoln had bought, among other things, a three thousand dollar point lace shawl, and Mrs. Grimsley had also indulged, to the extent of one thousand, in a like purchase…’ Mrs. Grimsley remarked dryly that was the nearest she ever came to having such a shawl.”7

Most of Mrs. Lincoln’s purchases during that first year involved her planned redecoration of the White House, for which $20,000 had been appropriated by Congress. Biographer Ruth Painter Randall wrote: “Old receipted bills in the National Archives show the vast array of objects bought. There is every possible item of furniture for Victorian interiors: bedsteads, chairs, sofas, velvet hassocks, ‘Bell Pull Rosets & Cords,’ washstands, ‘Ewers & Basins,’ ‘Covered Chamber,’ ‘foot bath,’ and — to strike a modern note — ‘Patent Spring Mattresses.’ One almost wades through costly fabrics: damask, brocade, pink tarlatan, ‘French Brocatelles,’ ‘French Plushes,’ ‘French Satin DeLaine.’ There is even an item for ‘hanging 221 pieces of velvet paper.’ It took 508 yards of blue and white “Duck’ for the tent placed on the White House lawn for the use of the Marine Band in their Wednesday and Saturday concerts.”8

Historian Leech noted: “Two months after inauguration, she [Mary Lincoln] paid a visit to New York with Mrs. [Elizabeth] Grimsley, and purchased a solferino and gold dinner service, with the arms of the United States emblazoned on each piece. She also selected some handsome vases and mantel ornaments for the Blue and Green Rooms, and ordered a seven-hundred-piece set of Bohemian cut glass.” New York merchants welcomed these visits with open lines of credit.

Mrs. Lincoln’s redecorating exceeded the congressional appropriation by over $6000 — leading to one of the First Lady’s periodic pecuniary panics. Mrs. Lincoln sought help from Benjamin Brown French, federal Commissioner of Public Buildings: “About 7 [Friday, December 13] Mrs. Lincoln sent down for me to go up and see her on urgent business. I could not go, of course, but sent word I would be up by 9 A.M. Saturday. Although suffering with a severe headache I went & had an interview with her, and with the President, in relation to the overrunning of the appropriation for furnishing the house, which was done, but the law, ‘under the President.’ The money was actually expended by Mrs. Lincoln, & she was in much tribulation, the President declaring he would not approve the bills overrunning the $20,000 appropriated. Mrs. L. wanted me to see him & endeavour to persuade him to give his approval to the bills, but not to let him know that I had seen her! I accordingly saw him; but he was inexorable. He said it would stink in the land to have it said that an appropriation of $20,000 for furnishing the house had been overrun by the President when the poor freezing soldiers could not have blankets, & he swore he would never approve the bills for flub dubs for that damned old house! It was[,] he said[,] furnished well enough when they came — better than any house they had ever lived in — & rather than put his name to such a bill he would pay it out of his own pocket! So my mission did not succeed. It was not very pleasant to be sure, but a portion of it very amusing.”9

The expenses which most upset the President came not from New York merchants but a Philadelphia decorator named Carryl who had purchased wallpaper and carpets for the White House. When Mr. Lincoln reviewed Carryl’s bill for a $2500 carpet, he demanded “to know where a carpet worth $2,500 can be put.” When French suggested the East Room, Mr. Lincoln said, “No, that costs $10,000, a monstrous extravigance [sic].”10

“By 1864 Mary Lincoln had become a campaign issue herself,” wrote biographer Jean H. Baker. “Benjamin French reported ‘rumors that Democrats are getting up something in which they intend to show up Madame Lincoln.’ And Republicans from Philadelphia and New York worried that unpaid merchants would embarrass the President by revealing the cost of her clothes.”11 Mrs. Lincoln herself thought those Republicans should do more than worry. “The Republican politicians must pay my debts,” she said privately. “Hundreds of them are getting immensely rich off the patronage of my husband, and it is but fair that they should help me out of my embarrassment. I will make a demand of them, and when I tell them the facts they cannot refuse to advance whatever money I require.”12

In the middle of the campaign September 1864, Mrs. Lincoln wrote Abram Wakeman about criticism of her spending in the New York World: “With such an establishment to keep up, you may imagine we have not enriched ourselves. In truth, I have had to endeavor to be as economical as possible; more so than I have ever been before in my life. It would have been a great delight to me to have had the means to entertain, generally as should be done at the executive Mansion, it would have been my pride and pleasure, so when the World dares to insinuate aught against us, the public should taken them in hand.”13

Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress and friend, Elizabeth Keckley, later explained her spending: “Mrs Lincoln was extremely anxious that her husband should be re-elected President of the United States. In endeavoring to make a display becoming her exalted position she had to incur many expenses. Mr. Lincoln’s salary was inadequate to meet them, and she was forced to run in debt, hoping that good fortune would favor her, and enable her to extricate herself from an embarrassing situation. She bought the most expensive goods on credit, and in the summer of 1864 enormous unpaid bills stared her in the face.”14

“My mother is on one subject not mentally responsible,” Robert Todd Lincoln wrote fiancée Mary Harlan in 1867.15 When Mrs. Keckley asked her employer about her debts, Mrs. Lincoln replied: “They consist chiefly of store bills. I owe altogether about twenty-seven thousand dollars; the principal portion at Stewart’s, in New York.”16 In other words, Mrs. Lincoln had rung up debts in excess of the spending on redecorating the White House which had so enraged the President in 1861. Supreme Court Justice David Davis, who was executor of President Lincoln’s estate, had breakfast with another friend of Mr. Lincoln, Orville H. Browning, in July 1873. Browning wrote in his diary: “He told me that after Mr Lincoln’s death a bill was presented to him as adm[inistrator of the president’s estate] by a merchant of New York for $2,000, for a dress for the last inauguration; a very large bill for furs, the amount of which I do not remember, and a bill by Mr Perry, a merchant of Washington for 300 pairs of kid gloves, purchase by her between the first of January and the death of Mr Lincoln, all of which he refused to pay; and that the only bill which had been proven against the estate, and which he had paid, was one for $10 for a country newspaper, somewhere in Illinois. He also told me that Simeon Draper had paid her $20,000 for his appointment as cotton agent in the city of New York.”17

Mrs. Lincoln went on: “You understand, Lizabeth, that Mr. Lincoln has but little idea of the expense of a woman’s wardrobe. He glances at my rich dresses and is happy to believe that the few hundred dollars that I obtain from him supply all my wants I must dress in costly materials. The people scrutinize every article that I wear with critical curiosity. The very fact of having grown up in the West, subjects me to more searching observation. To keep up appearances, I must have money — more than Mr. Lincoln can spare for me. He is too honest to make a penny outside of his salary; consequently I had, and still have, no alternative but to run in debt.” This debt had been contracted despite the fact that Mrs. Lincoln had worn nothing but black from the death of her son Willie in February 1862 until January 1, 1864.

Mrs. Lincoln had kept her husband in strict ignorance of her spending. “God, no!” replied Mrs. Lincoln when Mrs. Keckley asked if Mr. Lincoln knew how much she owed. “If he knew that his wife was involved to the extent that she is, the knowledge would drive him mad. He is so sincere and straightforward himself, that he is shocked by the duplicity of others. He does not know a thing about any debts, and I value his happiness, not to speak of my own, too much to allow him to know anything. This is what troubles me so much. If he is elected, I can keep him in ignorance of my affairs, but if he is defeated, then the bills will be sent in, and he will know all.”18

Biographer Ruth Painter Randall wrote: “Mrs. Lincoln also confided her troubles about her debts to Isaac Newton, Commissioner of Agriculture. John Hay several years later called on ‘Father Newton,’ as he called him, and the gossipy old fellow began to talk about Mrs. Lincoln. ‘Oh,’ he said (according to Hay) ‘that lady has set here on this here sofy [sic] and shed tears by the pint and begging me to pay her debts which was unbeknown to the President.”19

After Mr. Lincoln’s assassination, Mrs. Lincoln tried a series of increasingly desperate methods to pay off her debts — including enlisting Mrs. Keckley in 1867 in a bizarre attempt to sell her clothes anonymously in New York City.

Footnotes

- Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave, p. 197 (Although Keckly’s name has traditionally been spelled “Keckley,” Fleischner contends that “Keckly” was the spelling that Mrs. Lincoln’s seamstress and friend herself used.).

- Ishbel Ross, The President’s Wife: Mary Todd Lincoln, p. 126.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 149.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 309-310.

- Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship Between a First Lady and a Former Slave, p. 219.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 291 (New York Herald).

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biographer, p. 232.

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biographer, p. 232.

- Donald B. Cole and John J. McDonough, editor, Witness to the Young Republican: A Yankee’s Journal, 1828-1870, Benjamin Brown French, p. 382.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 294.

- Jean H. Baker, Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biographer, p. 235.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 151.

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 180-181 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Abram Wakeman, September 23, 1864).

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 147.

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 299.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 149.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings, p. 187.

- Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, p. 149-150.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 311.