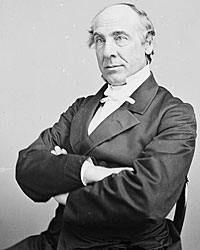

“The Doctor is alike eminent for eloquence, piety and a large acquaintance with the progress of the age in development of humanity,” wrote New York businessman Moses H. Grinnell in introducing the Rev. Dr. Henry W. Bellows to the President in May 1861.1 His First Congregational Church, located in Gramercy Park, included its congregation some of New York’s most prominent residents including Peter Cooper, Parke Godwin, and William Cullen Bryant. Henry W. Bellows was a well respected Unitarian clergyman, social mixer, and a born organizer.

The jewel of his organizing talents was the United States Sanitary Commission. George Templeton Strong, a New York lawyer who himself was a founding member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, wrote that Henry W. Bellows “has his foibles, and they lead many people to underrate him. Though public-spirited and unselfish, farsighted and wise (never foolish if he give himself time to take counsel with slower men, like [William H.] Van Buren, [Cornelius R.] Agnew, [Oliver W.] Gibbs, or myself), he is conceited and he likes to be conspicuous. But what a trifling drawback it is on the reputation of a man admitted to be sagacious, active, and willing to sacrifice personal interests in public service, to admit that he knows, after all, that he is doing the country good service, and that he likes to see his usefulness made manifest in newspapers.”2

Bellows’ work was great in scope and impact with the founding in April 1861 of what became the United States Sanitary Commission that would work for the health, nutrition, sanitation and hospital care of Union soldiers. “Bellows said afterward that when he and his associates founded the Sanitary Commission they had in mind, unconsciously at first, a wider objective than mercy for the suffering,” wrote Will Irwin, Earl Chapin May and Joseph Hotchkiss in A History of the Union League Club. The commission organizers sought to pull the nation together. “They expected northern sympathy with their point of view, and in the end they got more of it than was comfortable for the burdened Lincoln. This organization, uniting people of all states in a common purpose, could be and proved to be a powerful agent of propaganda for the nation as against the mere state.”.”3

Dr. Bellows was an active leader — inside and outside of the Unitarian Church of All Souls which he pastored for his entire ministerial life. He joined the church right after graduation in 1839 from Harvard Divinity School. The Church of All Souls itself was a major New York institution whose members included industrialist Peter Cooper, editor William Cullen Bryant, novelist Herman Melville, and nursing pioneer Louisa Lee Schuyler. Dr. Bellows was also a major unifying force among Unitarians — editing their publications, The Liberal Christian and the Christian Inquirer, and serving as president of the denomination.

The preacher was a moving force in the founding of Antioch College in Ohio and the Union League Club in New York. None of Dr. Bellow’s activities, however, put him in contact with Mr. Lincoln before the Civil War. Biographer Walter D. Kring observed: “The first indication that he was interested or knew about Abraham Lincoln is found in a letter to Mrs. George Schuyler in March 1860. He agreed with Eliza Schuyler in her estimate of a speech which William Seward had recently delivered, and then he wrote, ‘Did you read Mr. A. Lincoln’s — which in many ways is better? A more solid, statesmanlike Mss, we have not had, from any quarter. It proves what others simply grasp at, or abstract.'”4 He continued, however, to be a supporter of Secretary of State William H. Seward but cheered the election of Mr. Lincoln that November.

The Bellows’ family did develop an important connection to the Lincolns in early 1861. Son Russell was a Harvard classmate of Robert Todd Lincoln, who accompanied his father to Washington in February 1861. On his return to classes, Russell Bellows wrote that Bob was “as far as I can see, the same old sixpence. His father’s position doesn’t affect Bob’s manner at all. He has no airs or graces, & never will have the latter. He will probably ‘bleed’ his father’s pocket-book pretty extensively.”5 A few months later, Russell’s father wrote him: “Mrs. Lincoln, the President’s wife, consents to Bob’s going on & spending the vacation with you. Ask him in your own & my name & press it on him.” Dr. Bellows followed up that letter with a more explicit note to his son about his own political objectives concerning the President: “I am destined (I fear) to be more or less in Washington during the war, & it would facilitate my objects to have a connecting link with the President & his family. Enough said.”6

Even before he took up his charitable mission, Bellows preached the Union cause from the pulpit. Bellows biographer Walter D. Kring wrote: “As one of the leading spokesman of the day, Henry Bellows attempted to work out with as much clarity as he could his own moral support of the war…He believed that it was God’s will that men should ‘defend the sacred interests of society.’ A week later in another sermon Bellows developed his theme further. This time he claimed the church is concerned about the interests of the state. He defined the state as ‘nothing less than the great common life of a nation, organized in laws, customs, institutions, its total being incarnate in a political unity, having common organs and functions; a living body, with a head and a heart…with a common consciousness….The state is indeed divine, as being the great incarnation of a nation’s rights, privileges, honor and life…..'”7

“We have then, a holy war on our hands — a war in defence of the fundamental principles of this government — a war in defence of American nationality, the Constitution, the Union, the rights of legal majorities, the ballot-box, the law,” Rev. Bellows told his congregation nine days after Fort Sumter was bombarded in April 1861. “We must wage it in the name of civilization, morality, and religion, with unflinching earnestness, energy, and self-sacrifice.”8 Bellows was a dynamic speaker, noted friend George Templeton Strong who himself belonged to the Episcopalian Trinity Church: “Dr. Bellows has a most remarkable faculty of lucid, fluent, easy colloquial speech and sympathetic manner, with an intensely telling point every now and then, made without apparent effort.”9

At the end of April 1861, the Women’s Central Association was organized to help assist the war effort. More than 4,000 New York women showed up for its first meeting, which was attended by Rev. Bellows and Vice President Hannibal Hamlin. Facilities were provided by Peter Cooper, the industrialist who founded of Cooper Union. Although several doctors and other men such as Bellows were appointed to lead the organization, it was the women who did the work — such as Louisa Lee Schuyler who ran the association office.

It became obvious to the organizers that an official relationship to the federal forces was needed so Bellows went to Washington to meet with government officials. “Every door has opened at our bidding from the President down all the way through the cabinet to the bureaus — & it would almost seem as if we had only to speak our will & have it done,” the minister wrote his wife. “If you had seen your humble husband haranguing the President at the head of his committee, & then the Generalissimo of the Army, & then the Major Generals & the Brigadiers — (getting a colonel deposed for drunkenness, & one regiment out of rotten quarters into safe ones) — & then all the cabinet officers in turn, — you would really have fancied him suddenly promoted into the office of premier.”10

Dr. Bellows wrote that President Lincoln was “a good, sensible, honest man, utterly devoid of dignity — without that presence that assures confidence in his adequacy to his trying position.”11 The New York preacher admired Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase and distrusted Secretary of State William H. Seward. Secretary of War Simon Cameron was overwhelmed by his military duties — and had little concept of how to handle Bellows’ request. The minister continued to lobby strongly for appointment of a Sanitary Commission to assist in protecting the health and welfare of Union soldiers. Biographer Walter D. Kring wrote: “On 20 May Bellows talked with the President privately for half an hour in a ‘plain manner on the subject of my mission. He appeared much better than on the last interview, & I felt that he would probably grow upon acquaintance.’ He felt that the work was moving ahead. The next day Bellows gave up any idea of returning to New York in the immediate future. ‘I am so near a result that I do not dare to let go my hold.’ He believed that ‘the amount of sickness & suffering among the troops forbids my neglecting anything I can possibly do to bring the matter home to the government.’ [Chief Army Nurse] Dorothea Dix had begged him to remain, and ‘a powerful committee from New York is expected here tomorrow evening.'”12

The New York visitors — which included three physicians, Harris, W.H. Van Buren and Jacob Hansen — lobbied the War Department to build a public-private partnership to assist in developing living conditions. It was hard going, but by Bellows’ second trip to Washington in early June, he was able to claim success. The U.S. Sanitary Commission was officially appointed on June 9 with Bellows as its president and with advice its own real tool. Bellows was indefatigable over the next four years in his lobbying of the Lincoln Administration on behalf of the Commission — as this excerpt from George Templeton Strong’s diary entry in April 1862 shows:

This is all by way of prologue to Dr. Van Buren’s narrative. The Secretary of War telegraphed for him to come to Washington. (He did not send for Hammond.) Bellows went with him. Van Buren reported at the War Department, and the Secretary asked frankly what he should do with the Medical Bureau. “I have called you into a bad case.’ ‘What are the symptoms, Mr. Secretary?” “General imbecility.” They had more than one free discussion, and Van Buren submitted a list of names for the new offices with Dr. [William] Hammond at their head, and [Edward P.]Vollum and [Lewis] Edwards of the regular corps, and R. Lyman and Dr. [Meredith] Clymer of the volunteers, and so on, which the Secretary approved. Then it appeared that Lincoln had been subjected to political pressure and was, moreover, influenced by personal regard for our excellent old colleague, Dr. Wood, who hates Hammond. The medical staff judges of its members by their military record rather than by scientific or professional rank. Bellows tackled Lincoln while he was being shaven [the] next (Thursday) morning and seems to have talked to him most energetically and successfully. He was with the President again last night and was informed that Hammond was appointed. ‘Shouldn’t wonder if he was Surgeon-General already,’ said the President, and they shook hands upon it. I believed this, coming from Lincoln, but I wouldn’t believe it if it came from any other Washington official. “I hain’t been caught lying yet, and I don’t mean to be,” said Abe Lincoln, during their discussion, and such is probably the fact.”Another Lincoln [story]. Dr. Bellows, apropos of something he said, advised him to take his meals at regular hours. His health was so important to the country. Abe Lincoln loquitur, ‘Well, I cannot take my vittles regular. I kind o’ just browze round.’ He says, ‘Stanton’s one of my team, and they must pull together. I can’t have any one on ’em a-kicking out.'”13

The commission required the cooperation of the government to do its work, but frequently that cooperation was given grudgingly if at all. The Commission’s relations with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton were frequently contentious. After Dr. Bellows visited him in April 1863, Strong wrote: “Stanton said he had not intended to attack the Sanitary Commission and had not foreseen the injury his order would do the Commission, but that he did not want to revoke or retract anything at its request or to promote its objects. He was no friend of the Commission — disliked it, and in fact, detested it. ‘But why, Mr. Stanton, when it is notoriously doing so much good service, and when the Medical Department and the whole army confide in it and depend on it as you and I know they do?’ ‘Well,’ said the Secretary, ‘the fact is the Commission wanted [Dr. William A.] Hammond to be Surgeon-General and I did not. I did my best with the President and with the Military committee of the Senate, but the Commission beat me and got Hammond appointed. I’m not used to being beaten, and don’t like it, and therefore I am hostile to the Commission.”14

In the spring, Bellows took a trip aboard a hospital ship to the Jamestown Peninsula before returning to Washington to straighten out administrative matters. “Bellows had waited in Washington for the return of President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton because the government had been procrastinating in the appointment of the persons authorized by the Medical Bill,” wrote biographer Walter D. Kring. “Bellows cooled his heels and waited. Eventually it became necessary from the standpoint of the Sanitary commission which had worked so hard getting the bill framed and through Congress that he do something. He called on Stanton on the morning of 13 May. He had waited fifteen minutes and was starting down the stairs when Stanton came up.” Stanton was tired and out of sorts. “Amid obvious hostility Bellows pressed Stanton, expressing hope that the appointments under the new bill would be made as soon as possible. Stanton tested Bellows by asking what his concern was in all of this Bellows replied, ‘We know who the proper men are, and have presented them in a letter Dr. Van Buren has left with you. There may be other men as good — be we do not feel that there are. The service is suffering immensely for prompt action in this matter, and we cannot feel easy while this action is delayed, or willingly see it take a wrong direction.”15 Strong reported in his diary: “After dinner came in Bellows fresh from a row with the Secretary of War about appointments under the Medical Reform Bill, in which Stanton was petulant and insolent and then emollient and apologetic. Bellows thinks he has some cerebral disease.”16

The head of the Army’s medical department, known as the Surgeon General, was particularly important to the Sanitary Commission’s work. Artist Francis Carpenter spent several months working at the White House and later wrote:

“The Rev. Dr. Bellows, of New York, as President of the Sanitary Commission, backed by powerful influences, had pressed with great strenuousness upon the President the appointment of Dr. Hammond, as Surgeon-General. For some unexplained reason, there was an unaccountable delay in making the appointment. One stormy evening — the rain falling in torrents — Dr. Bellows, thinking few visitors likely to trouble the President in such a storm, determined to make a final appeal, and stepping into a carriage, he was driven to the White House. Upon entering the Executive Chamber, he found Mr. Lincoln alone, seated at the long table, busily engaged in signing a heap of congressional documents, which lay before him. He barely nodded to Dr. Bellows as he entered, having learned what to expect, and kept straight on with his work. Standing opposite to him, Dr. B, employed his most powerful arguments, for ten or fifteen minutes, to accomplish the end sought, the President keeping steadily on signing the documents before him. Pausing, at length, to take breath, the clergyman was greeted in the most unconcerned manner, the pen still at work, with, — ‘Shouldn’t wonder if Hammond was at this moment ‘Surgeon-General,’ and had been for some time.’“You don’t mean to say, Mr. President,’ asked Dr. B in surprise, that the appointment has been made?”“I may say to you,” returned Mr. Lincoln, for the first time looking up, ‘that it has; only you needn’t tell of it just yet.”17

But the appointment merely exacerbated Stanton’s enmity. Strong wrote in his diary in April 1863: “Bellows just returned from Washington and General Hooker’s headquarters, and told me part of his experiences this afternoon. The War Department has issued an order (No. 87, I think) about the transportation of medical and sanitary stores that seriously curtails the privileges government gives us. I think it was issued inadvertently and in no unfriendly spirit, but Dr. Bellows declares he will resign and make open war on Stanton unless it is resolved or corrected by an explanatory order. He discussed the matter with the solicitor of the War Department (Whiting), an old college friend of his; and in confidential relations with Stanton, Whiting brought the matter before his chief.”18

According to Strong, Secretary of State William H. “Seward told Dr. Bellows that the President and the Cabinet were strong in approval of the Commission; that they had consented to recognize an outside agency and give it a semi-official position very reluctantly, and only because they could not properly say no, and that they had taken it for granted the Commission would collapse and die a natural death within a year after its appointment at latest. But ‘the Commission has made itself a necessity, and it has done its very difficult and delicate work with so much discretion, tact and ability, that’ — and so forth.”19

Just as President Lincoln’s support for the commission increased over time, so did Bellows’ support for President Lincoln increase with time. According to biographer Walter D. Kring, Bellows observed “that it was not only the men who were active in politics this year but the women, who, although they had not vote, made it a point to attend the campaign meetings. For six months in mid 1864, Bellows was absent from New York. He traveled to California in the spring of 1864, remaining for six months and preaching in San Francisco — while raising funds for the Sanitary Commission. Bellows returned to New York City in time to address 3,000 people at the Cooper Institute and had talked for an hour and a quarter ‘at one of the most successful campaign meetings.'”20

Bellows colleague William E. Dodge, Jr. recalled: “There are times when to invent a happy phrase is equal to the winning of a martial victory. As Mr. Seward’s phrase’ the irrepressible conflict’ formulated the situation which preceded and developed the war, so Dr. Bellows’ phrase ‘Unconditional Loyalty’ formulated the necessity of the time when war had actually begun. This phrase brought into existence the New York Union League, the child of the Sanitary Commission, the details of whose organization were worked out by Dr. Bellows and two other officers of the Sanitary Commission on a night-journey from Washington to New York. The government did well to circulate 10,000 copies of Dr. Bellows’ sermon on ‘Unconditional Loyalty’ among the officers of the army and navy.”21

Although he attended President Lincoln’s funeral on April 1865, Dr. Bellows was not impressed by it. He wrote that “a little before twelve we marched to the White House through the grounds that separate it from the Treasury, were shown into the East Room and took our appointed places on the raised steps that occupied three of the sides — the catafalque with its black canopy and open coffin occupying the center. I had a last glimpse of the honest face of our great and good President as we passed by. It was darker than in life, otherwise little changed…”22 Bellows wrote that “the actual service was common-place, & did not voice the occasion, but it could not belittle or stifle it. It was in itself too great & too speaking for that. The grief was genuine profound & all pervading.”23 Of the President’s death itself, Bellows asked his congregation: “May we not have needed this loss to sober our hearts in the midst of our national triumph, lest in the excess of our joy and pride we should overstep the bounds of that prudence and the limits of that earnest seriousness which our affairs demand?”24

Footnotes

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 231.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 425 (April 4, 1864).

- Will Irwin, Earl Chapin May and Joseph Hotchkiss , A History of the Union League Club , p. 8.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 216.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 221.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 234.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 221.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 226.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 277 (December 11, 1862).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 232 (Letter from Henry W. Bellows to Eliza Bellows).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 233.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 233.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 218 (April 19, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 314 (April 25, 1863).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 250-251.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 226 (May 15, 1862).

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 274-275.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 313-314 (April 25, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 314-315 (April 25, 1863).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 300.

- In Memoriam, Henry Whitney Bellows, D.D., G.P. Putnam’s New York, April 13, 1882, p. 17-18 (William E. Dodge Jr.).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 323.

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 323.

- David B. Chesebrough, No Sorrow Like Our Sorrow: Northern Protestant Ministers and the Assassination of Lincoln, p. 75.

Visit

Moses H. Grinnell

Frederick Law Olmsted

William H. Seward

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Edwin M. Stanton (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Edwin M. Stanton (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

George Templeton Strong

Ministers

Biography (members.tripod.com)