Thurlow Weed was no saint. He was best known as a successful editor, a successful political leader and a successful businessman. But, Weed was also noted for his quiet philanthropy. In addition to helping their own military personnel, New Yorkers undertook altruistic enterprises in regard to British textile workers who suffered from the embargo on Southern cotton. In December 1862, Weed wrote businessman Robert B. Minturn, enclosing a check of $1,000:

I am happy to learn that the enterprise about which we conversed in New York on Tuesday last has been auspiciously inaugurated. The organization effected in New York will speedily aggregate the contributions of our citizens, and relief will soon be on its way to the suffering families of the cotton manufacturing districts of England.There can be no form of suffering which appeals with such emphasis to intelligent American benevolence. Our unavoidable civil war is the immediate through blameless occasion of the want of employment and food which pervades and desolates the manufacturing towns of England. Their distress, therefore, appeals as earnestly to our heads as to our hearts. Nor is the fact that our war leaves the laborers of Lancashire without employment, and their families without bread, their only claim upon us. They are our friends. While the sympathies of many of the commercial classes of England are with the insurgent States, while the cotton houses of Liverpool were furnishing ‘material aid’ to the Confederates, the operatives of the cotton districts and their representatives in Parliament resisted efforts to secure cooperation against our blockade and in favor of foreign intervention.1

The Civil War brought out a powerful combination of leadership from businessmen and clergy in New York. They joined journalists and politicians in giving New York City politics a special civic flavor. The lines among these occupations were not rigid. Democratic National Chairman August Belmont was a successful businessman and a co-owner of the New York World. Democratic Congressman Benjamin Wood, brother of erstwhile Mayor Fernando Wood, ran the New York Daily News. Edwin D. Morgan, New York’s governor and later senator, was one of the city’s most successful businessmen. George Templeton Strong, who has a member of United States Sanitary Commission, was an active member of the Vestry of Trinity Church and a dedicated trustee of Columbia College. The Sanitary Commission chairman, the Rev. Henry W. Bellows, spent more time tending to the physical welfare of Union soldiers than to the spiritual welfare of his Unitarian parishioners.

Leading clergy and businessmen shared charitable roles. Businessman Henry C. Bowen was a pillar, perhaps the pillar of Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church where Henry Ward Beecher was pastor. Bowen was also the owner of The Independent, which Beecher helped edit. And it was Bowen who acted as one of Mr. Lincoln’s hosts when he came to New York City in February 1860 to give his speech at Cooper Union. Beecher biographer Paxton Hibben wrote:

Whether civil war was to follow the election of Abraham Lincoln or not depended a vast deal on just such men as Henry Ward Beecher. Everybody knew where Garrison and Wendell Phillips and Theodore Tilton and others of the leftwing Abolitionists stood. But it was men like Greeley and Beecher, first on one side and then on the other, and great numbers of bewildered folk who read the Tribune and attended Plymouth church, who held the balance of decision. In Plymouth Church, ‘up to the time of the war, slavery was not made the subject of discussion more than once or twice a year,’ says Beecher.2

A paragraph in Joseph Howard’s biography of Henry Ward Beecher suggests the kinds of interrelationships between the fields of politics, religion and journalism that characterized New York in the 1860s: “In the early days of Mr. Beecher’s Brooklyn ministry, Theodore Tilton and Elizabeth Richards, young members of Plymouth Church, were married. Tilton was a reporter on the Tribune and reported Mr. Beecher for the Independent. When Beecher became editor of the Independent, Tilton was engaged as his assistant. They were warm friends, and interchanged visits, although those of Tilton were discouraged by Mrs. Beecher, who never fancied him. As time wore on, Tilton, encouraged and aided by the countenance of his pastor, essayed public speaking and, having adopted his anti-slavery ideas, was soon a favorite with extreme abolitionists. He succeeded Mr. Beecher when the latter left the Independent, and was persuaded by his friends that his pastor was the one man who stood between him and the chief place among the orators of the nation. So far as the outside public knew, the two men were like David and Jonathan….” 3

Although Beecher first sought concessions with the South when in the early days of secession, the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 made Beecher fighting mad and a firm advocate of slavery’s abolition. “Since war is upon us, let us have the courage to make war,” declared Beecher.4 And Beecher made war. According to biographer Hibben, “Henry Ward addressed recruiting meetings, blessed flags, preached warlike sermons and wrote warlike articles for The Independent. He was as busy as a Major General — and a good deal busier than some of the Major Generals at that juncture. He ran down to Washington to see why his son’s regiment was not sent to the front at once, helped to get boys into the army — or out of it — organized welfare work for the soldiers, and a hundred other things. But mostly he exercised the inalienable right of non-combatants in time of war to criticize the government.”5

Many businessmen followed the lead of New York City women in developing philanthropic enterprises during the Civil War. One of the products of their enterprise was the U.S. Sanitary Commission — which was driven by the combined leadership of physicians, clergy, attorneys, businessmen and a landscape architect named Frederick Law Olmsted. The country was unprepared for war and even more unprepared for how to deal with the casualties of war and the health, diet, and sanitary challenges of military encampments.

The New York leadership group rose to the challenge of how to assist in the war effort without putting on uniforms. Speaking of Dr. Henry W. Bellows, businessman William E. Dodge, Jr. recalled: “The question of his own personal duty in the coming crisis oppressed him. He knew how many homes must be desolated, how many brave men must leave every thing dear to them, to sustain so sacred a cause. And how could he urge others to go and himself remain behind? He felt himself unfitted for the life of the camp and surrounded by a complicated network of parish and professional duties, from which he saw no escape.” Dodge said: “I cannot forget the joy that brightened his face when he saw, in the formation of the ‘Women’s Central Association of Relief,’ an opening for all his powers and a sphere where his peculiar abilities could tell best for his country. In this field he could carry out the strongest impulse of his life, — the bringing comfort and help to others.”6

Civic duty and humanitarian concern propelled the commission’s leadership. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “A great clergyman and a great physician, Dr. Bellows and Dr. William H. Van Buren, labored frenziedly to create the Sanitary Commission. They obtained due powers from President Lincoln and Secretary of War [Simon] Cameron. They forced a weak Surgeon-General, Dr. [Clement A.] Finley, to abandon his opposition. They gathered a strong body of commissioners…They established a nation-wide machinery for collecting supplies and money.”7 As a result of their pressure, President Lincoln issued an “Order Establishing the Sanitary Commission” on June 9, 1861:

The Secretary of War has learned, with great satisfaction, that at the instance and in pursuance of the suggestion of the Medical Bureau, in a communication to this office, dated May 22, 1861, Henry W. Bellows, D.D., Prof. A.D. Bache, L.L.D., Prof. Jeffries Wyman, M.D., Prof. Wolcott Gibbs, M.D., Wm.H. Van Buren, M.D., Samuel G. Howe, M.D., R.C. Wood, Surgeon U.S.A., G.W. Cullum, U.S.A., Alexander E. Shiras, U.S.A., have mostly consented, in connection with others as they may choose to associate with them, to act as ‘A Commission of Inquiry and Advice in respect of the Sanitary Interests of the United States Forces,’ and without remuneration from the Government. The Secretary has submitted their patriotic proposal to the consideration of the President who directs the acceptance of the services thus generously offered.The Commission, in connection with a Surgeon of the U.S.A., to be designated by the Secretary, will direct its inquiries to the principles and practices connected with the inspection of recruits and enlisted men; the sanitary condition of the volunteers; to the means of preserving and restoring the health, and of securing the general comfort and efficiency of the troops; to the proper provision of cooks, nurses, and hospitals; and to other subjects of like nature.The Commission will frame such rules and regulations, in respect of the objects and modes of its inquiry, as may seem best adapted to the purpose of its constitution, which, when approved by the Secretary, will be established as general guides of its investigations and action.A room with necessary conveniences will be provided in the City of Washington for the use of the Commission, and the members will meet when and at such places as may be convenient to them for consultation, and for the determination of such questions as may come properly before the Commission.In the progress of its inquiries, the Commission will correspond freely with the Department and with the Medical Bureau, and will communicate to each, from time to time, such observations and results as it may deem expedient and important.The Commission will exist until the Secretary of War shall otherwise direct, unless sooner dissolved by its own action.8

Women played a key role in the real work of the commission. Historian John William Leonard wrote that the commission “began, as many organizations of mercy have begun, in the work of devoted women, who, soon after the Union Square meeting of April 20th [1861], organized the Woman’s Central Association of Relief for the Sick and Wounded of the Army. Upon the advice of Rev. Henry W. Bellows, D.D., a committee, representing the association and some medical relief associations of New York, went to Washington to confer with the authorities in War Department as the needs of the service and the best means of supplying them, and from the conference came the organization of the United States Sanitary Commission, which, under the general direction of Rev. Dr. Bellows, its president, became the most successful agency of help and comfort to sick and wounded soldiers the world had ever seen.”9

First, bureaucratic inertia in Washington had to be overcome. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The Sanitary Commission had sprung into formal existence on June 9. Dr. [Robert C.] Wood, as head of the Medical Bureau of the Army, had at first taken a hostile attitude. But the able delegation which the several relief organizations of New York sent to Washington had irresistible arguments at their command. They pointed to the gross neglect of sanitation in the camps; the scandalous lack of materials and nurses to care for the wounded in any great battle; and the necessity of setting up some body to utilize the contributions which the people were anxious to make for the well-being of the troops. At first they hoped for a Sanitary Commission which (like the British commission in the Crimea) would have plenary power to carry its recommendations into effect. When Dr. Wood declared that his Medical Bureau would never consent to such a plan, they modified it. Wood then gave way, and on May 22 wrote a letter to Secretary of War Cameron asking for the appointment of ‘an intelligent and scientific commission’ to cooperate with the Bureau in applying the best modern doctrines with respect to the diet, hygiene, and hospital care of the troops. Much tedious negotiation followed. Finally, on June 9 Cameron appointed Bellows, Bache, Gibbs, Van Buren, Wood, and others to the Sanitary Commission. They organized June 12, choosing Dr. Bellows president, and at their second meeting they elected Strong to membership, appointing him treasurer of the Commission — an onerous post.”10

The Bellows group “had been deeply impressed by the appalling loss of life by disease during the Crimean War, and they were determined that the United States should profit by the experience which Great Britain had gained at such fearful cost,” wrote historian Margaret Leech. “They wanted to form a scientific board which should have power to enforce sanitary regulations in the camps. Their hopes were soon dashed by contact with the antiquated machinery of the Medical Bureau. The meddlesome civilians were received with coldness, and discouraged by evasion and delay. But they were prominent gentlemen, and persistent, and at last they were grudgingly granted permission to act as an advisory board.”11 They were relentless in overcoming opposition from the War Department and the President himself. Politically, they took the path of least resistance by asking that the government appoint the Sanitary Commission as an investigative and advisory body. In a letter to Columbia academic Francis Lieber in July 1862, George Templeton Strong set out the reasons why the Sanitary Commission had been needed:

1. The Old Medical Bureau was, by the universal consent of all but its own members, the most narrow, hidebound, fossilized, red-tape-y of all the departments in Washington. It was wholly incapable of caring for the army when the war broke out. It was without influence or weight with Government. Lincoln actually did not know last September who the surgeon-general was. He said so in my presence.2. The Bureau was reorganized to some extent by Congress last April and an energetic young vigorous ambitious man put at its head. He is working hard. But the appointment of the new officers and additional surgeons under this act had been most criminally delayed, and without them, the new surgeon-general is almost powerless.3. Government has heretofore relied on the Hospital Fund system — i.e., purchase of hospital stores with proceeds of commutation of rations. This has worked well with regulars, but our volunteer regiments have not had experience enough to get this system adopted among them very generally, or in good working order.4. In fact, I believe the sufferings on both sides during the last Italian war exceeded those of our men. They certainly did so in the Crimea.5. The social status, education, and so forth of our volunteer rank and file, the life they have been used to at home, the attention they expect in sickness, make things necessary for them, which would be extravagant luxuries to the rank and file of any foreign army, and which it is questionable whether Government ought to supply.6. It is out of the question for Government to do all that is to be done immediately after severe fighting. It cannot be done even with volunteer aid. For instance, a regiment 1,000 strong after a day’s fighting leaves say 250 wounded men scattered over a mile square. To attend to these there are a surgeon and assistant, perhaps a hospital steward, a couple of ambulances at most, and the band (if any) to take charge of them — all unskilled laborers except the surgeon and assistant. The medical stores are at some depot four miles off. Is it not clear that a day must often elapse before these men can all be brought in and even looked at by their surgeon? Of course Government can do something toward alleviating all this — for example, it can increase the supply of ambulances and can make the medical staff numerically stronger. Both these measures are being pushed with the utmost vigor by Surgeon-General Hammond. But even with four surgeons to a regiment it seems clear that there must be more work after a severe engagement than they can possibly perform. Government cannot establish and keep in pay such a force as will make its medical department fully equal to such an emergency. Hence the absolute necessity of volunteers during active operations.But Government is responsible for the most abominable neglect, and deserves the severest censure for allowing a state of things to exist among troops when at rest, when no fighting is going one, which renders volunteer aid necessary even then. That is should depend on private charity for supplies for its hospitals at Washington is a disgrace. That it should put 2,000 typhoid cases at Yorktown in charge of a surgeon who could say, in answer to a question from one of our agents whether he had stimulants enough, ‘Yes — that is, I have not got any now. They were used up very fast, they are all gone, and I have not made a requisition for any more. No, I thank you, you needn’t send me any from your stores. The men die as a general rule anyway’ — that it should allow such a man to remain in its service one hour is a national crime.12

The Commission began by investigating conditions in Army encampments and preparing reports on how to improve living and health conditions. They also began to collect food and supplies through local organizations affiliated with the Commission. Commission inspectors were given lists of 180 criteria which they were to investigate and monitor for the Medical Bureau of the War Department. The mission of the Sanitary Commission would have seemed to have been commendable and straight-forward but it quickly ran into a series of obstacles, both personal and political. One was the old-line surgeon-general, R. C. Wood. Strong complained in his diary: “The old Surgeon-General has been making war on us through the Times. [Henry J.] Raymond is his personal friend. The attack has done us little harm. ‘Woe unto you when all men speak well of you.” If one’s attack on a hornet’s nest be really vigorous and useful, one must expect to be buzzed about, at least, if not severely stung.”13

The commission needed public as well as governmental support. Strong sought to mobilize newspaper opinion on the side of the commission. He wrote his diary: “Wasted two hours tonight with Dr. Peters in the Tribune, office, waiting to see [Charles] Dana — in vain. I want to enlist the Tribune against the Times, which continues to defend the imbecile Medical bureau by the dirtiest little suggestions of hostility to the Sanitary Commission. Raymond of the Times tells Dr. Agnew frankly and unblushingly that he is obliged to take this position because Dr. Finley is a friend of his. So it seems the Medical bureau will neither do its special duty and protect our soldiers nor allow a volunteer organization to make up for its shortcomings.” 14 A few months later, Strong recorded: “Much gratified by a letter from Raymond of the Times apologizing for the attacks that paper made on us last fall and winter, and sending us one hundred dollars as evidence of his conversion.”15 The commission also sought to recruit the assistance of a more powerful ally. On January 29, 1862, Strong reported:

Bellows and I called on the President yesterday to make the modest proposition that if any bill passed giving him power to appoint (doing away with the fatal principle of seniority), he would hear us before making any appointments. It was a cool thing. Lincoln looked rather puzzled and confounded by our impudence, but finally said, ‘Well, gentlemen, I guess there’s nothing wrong in promising that anybody shall be heered before anything’s done.’ We had the unusual good fortune to catch our Chief Magistrate disengaged, just after a Cabinet council, and enjoyed an hour’s free and easy talk with him. We were not boring him, for we made several demonstrations toward our exit, which he retarded severally by a little incident he remembered or a little anecdote he had ‘heered’ in Illinois. He is a barbarian, Scythian, yahoo, or gorilla, in respect of outside polish (for example, he uses ‘humans’ as English for homines), but a most sensible straightforward, honest old codger. The best President we have had since old Jackson’s time, at least, as I believe, for Zachary Taylor’s few days of official life can hardly be counted as a presidential term. His evident integrity and simplicity of purpose would compensate for worse grammar than his, and for even more intense provincialism and rusticity.

He told us a lot of stories. Something was said about the pressure of the extreme anti-slavery party in Congress and in the newspapers for legislation about the status of all slaves. ‘Wa-al,’ says Abe Lincoln, ‘that reminds me of a party of Methodist parsons that was travelling in Illinois when I was a boy thar, and had a branch to cross that was pretty bad — ugly to cross, ye know, because the waters was up. And they got considerin’ and discussin’ how they should git across it, and they talked about it for two hours, and one on ’em thought they had ought to cross one way when they got there, and another way, and they got quarrellin’ about it, till at last an old brother put in, and he says, says he, ‘Brethern, this here talk ain’t no use. I never cross a river until I come to it.'”16

The course of the Sanitary Commission’s progress was not easy. On February 18, 1862, Strong wrote: “Meeting of Executive Committee of Sanitary Commission at Dr. Bellows’s at two o’clock. Olmsted with us. We propose now to prepare, at least, to put our house in order, wind up our affairs, and resign. Government keeps no faith us. From last July till this time, there has been a series of promises unperformed. We got our hospitals erected, to be sure; General [Montgomery] Meigs kept his word with us. But that is the single exception. Mr. Secretary Cameron promised and repromised reforms, but nothing was done. McClellan has promised us general orders ‘this afternoon or tomorrow,’ begging us always to tell him what we thought necessary at once, but he has issued nary order on our suggestion. So with Lincoln. So with Stanton. It is nearly a month since he pledged himself, with apparent warmth, to decisive steps that have not been taken to this day. We cannot go on asking the community to sustain us with money as an advisory government organ after six months’ experience like this.”17 Bellows biographer Walter Kring noted “the more the members of the Sanitary Commission thought of disbanding the organization that had been put together with so much effort, the less it seemed to be the thing to do. The only thing that really hampered them were the finances.”18

Dogged efforts with both the executive and legislative branches were needed to achieve the commission’s goals. Margaret Leech wrote: “Indignant at being forced to continue the legitimate work of the Government, Mr. Olmsted and the other members of the commission determined that the Medical Bureau must be reformed. These gentlemen became vigorous lobbyists, and the medical bill which they assisted in preparing was passed by Congress in the spring of 1862 — too late to prevent he frightful neglect of the wounded in the campaigns of that season”.19

The Commission’s road continued to be rocky after it considered and rejecting dissolution in February 1862. But by April, Strong was able to report: “The Sanitary Commission is treated with profound respect by all Washington officials. Our relations with the government are now more intimate than they ever have been. We have carte blanche from the War Department as to hospitals at Yorktown.”20 Margaret Leech wrote: “For some time, the Sanitary Commission had been urging the appointment of Dr. William Alexander Hammond, an assistant surgeon who had attracted attention by his successful work in organizing hospitals and sanitary stations. On Finley’s resignation, the President was bombarded with petitions from doctors in favor of Hammond, and in late April, 1862, he was made Surgeon General.”21

The Commission’s difficulties never disappeared, however. Ten months later, Strong wrote: “Tonight the Executive Committee of Sanitary Commission met and supped at Dr. Van Buren’s. Talked mostly of the feud between [Edwin M.] Stanton and the Surgeon-General, and of measures to restore harmony between them, or to bring the case before the President or before the people. We came to no decision. Stanton seems trying to undermine Dr. [William A.] Hammond, refusing to let him send an inspector to the West or to go thither in person, and using the general complaint of inefficiency in the Western Department against him.”22 Dr. Hammond lasted 28 months until he was forced out by Stanton in 1864.

Although women were the driving impulse in New York’s assistance to servicemen, they were not always appreciated. Bellows biographer Walter D. Kring wrote that “the real work of making bandages and other comforts for the men at the fronts was carried on at The Women’s Central in Peter Cooper Institute and various other places. Anna Bellows says that ‘in All Soul’s Sunday school room…ladies met to prepare lint, bandages, havelocks, and the thousand and one things necessary for the comfort of the soldier, whether well or wounded. As the war went one, with all its horrors, the desire to save suffering increased, enthusiasm and zeal rose high. Hospitals, ambulances, doctors, surgeons, and nurses were needed to supplement those already on the battle-field.”23 New York women sewed 26,000 quilts for Union soldiers and like women across the North were key organizers of fund-raising events like the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair of March 1864 that raised $100,000 for the Commission. Women were also active in nursing and soldier care. Mayor George Opdyke’s wife organized the Ladies’ Home for Sick and Wounded Soldiers at 51st Street and Lexington Avenue.

The commission clashed with one fellow reform advocate — Dorothea Dix. After one meeting of the Sanitary Commission in July 1861, Strong reported: “We did a good deal of business. Extricated ourselves from an entanglement with that philanthropic lunatic, Miss [Dorothea L.] Dix, appointed four agents, or inspectors, Adopted Dr. Van Buren’s code of sanitary rules that is to be distributed among the volunteers and my draft of instructions to agents (without material alternation, strange to say), made sundry recommendations to Congress and the War Department, and so on.”24

But although the actions of Dorothea Dix might be scorned, the actions of women were not to be ignored, noted historian Paula Baker: “White women were not struggling against the bonds of slavery (although some were fond of such rhetoric), but some saw unparalleled opportunities in the war for advancing their causes and political influence. For Josephine Shaw Lowell, and no doubt other young, middle-class women with abolitionist ties, the early 1860s were ‘extraordinary times and splendid to live in. Such women seized the opportunity to press forward their political ideas. For the most radical — largely woman suffragists and abolitionists — there was the National Women’s Loyal League, founded in New York City in May 1863. Members ran petition drives aimed at pushing Lincoln further along an antislavery direction.”25

The bulk of the women’s work, however, was charitable — through leaders of the Woman’s Central Association of Relief such as Josephine Shaw Lowell, Louisa Lee Schuyler and Georgeanna Woolsey. They were organized, dedicated and committed to public health strategies that worked. Bellows’ friend William E. Dodge, Jr., wrote: “The noble women who led in this great work gathered from all the cities and villages and homes of the North needed supplies for the men in the field, and perfected an organization most perfect and wonderful. Their labor was exhaustive, wise, and far-reaching.”26

Historian Margaret Leech wrote: that “the Sanitary Commission might have remained little known to the general public, had it not been for the secondary phase of its activities — the distribution of supplies. By the sheer force of their patriotic benevolence, the ladies overwhelmed the scientific preoccupations of Dr. Bellows and Mr. Olmsted and their associates. Everywhere the war was bringing women out of the seclusion of domestic life. Timid ones grew bold as lions. Invalids arose from their sofas. To the astonishment of men, they were able to draft constitutions and bylaws, to serve on committees and presided at meetings; even to raise and handle money. From thousands of aid societies in all parts of the Union, a steady stream of stores flowed to the Sanitary Commission. Enriched by large donations, it established enormous storehouses, and administered them efficiently. It organized a relief service for hospitals and camps, and installed its own refreshment saloons. Trained agents, in charge of the commission’s wagonloads of supplies moved with every army. The name, which had been derived from an interest in preventive hygiene, became a household word; and everything sent to the soldiers, from current wine to Canton flannel drawers, went by the name of ‘sanitary stores.'”27

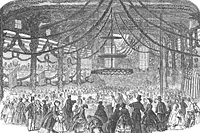

Historian John William Leonard wrote: “In the spring of 1864 the United States Sanitary Commission held a series of fairs in all the large cities, for the benefit of their work, and the most important of these was the great Metropolitan Fair, held in April, in two specially erected buildings, one in Fourteenth Street, near Sixth Avenue, and the other in Seventeenth Street, near Union Square. Many interesting booths were in both of the buildings, and the most beautiful and accomplished dams and young ladies of New York were in charge of the stalls. The fair netted $1,100,000 and a similar one, previously held in Brooklyn (in February), realized $300,000 for the commission.”28

Attention was also needed to the welfare of residents in New York City. “Neither the outbreak of war not the Emancipation Proclamation brought better times for the Negroes of New York. A free man in theory the Negro was actually a social and economic outcast. Segregation was the rule in New York City, in the schools and elsewhere. The unskilled laborers, largely Irish, heaped upon the colored people and their abolitionist friends the blame for inflation, the draft, high taxes, and casualties, Prejudice against the Negroes was common among most citizens of New York. For example, in 1860 the voters turned down by a wide margin an amendment granting the Negro the right to vote without meeting property qualifications. Mayor Fernando Wood of New York openly attacked the Negroes as inferior, and representatives of New York City in both the state and national legislatures undoubtedly reflected local opinion in opposing the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment,” wrote David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman in A History of New York State.29

Historian John Hope Franklin wrote: “The federal policy for relief of freedmen developed so slowly that private persons, both Negro and white, undertook to supplement it. As early as February, 1862, meetings were held in Boston, New York, and other Northern cities for the express purpose of rendering more effective aid to Southern Negroes. On February 22, the National Freedmen’s Relief Association was organized in New York…”30

Another organization that sought to assist black New Yorkers was the Union League. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “It was important to rally the loyal elements of the North in a demonstration of their strength, and Union meetings were held all over the country. In December 1862, a Union League Club had been organized in Philadelphia to lend support to the Administration; and now Strong was among the patriots who decided that a similar group must be formed in New York. Indeed, the Wolcott Gibbs, George F. Allen, and Professor Theodore W. Dwight were the leading spirits in founding the Club.”31 Historian Paula Baker wrote: “Some 350 men, appalled by the election of [Governor Horatio] Seymour and moved by a strong belief in the war, formed the club early in 1863. Their ambitions went well beyond a single election and even the war. Their concern was to promote nationalism over what they saw as narrow sectionalism and blind partisanship. The league, according to Frederick Law Olmsted — the landscape architect and former head of the United States Sanitary Commission — was a ‘true American aristocracy’ that could lead in building new institutions to bind a society divided by class, ethnicity, and race and create a powerful, centralized, Christian state. The members’ nationalism shaded into nativism. Publicly and privately some of them complained about the number and equality of immigrants entering the country, especially the Irish. They sought a paternalistic relationship with the working classes, in which honest, native-born laborers would sensibly follow elite guidance.”32

The Union League reflected the class structure of New York, according to historian Iver Bernstein: “The Union League Club disparaged arrivistes such as [financier August] Belmont and hoped to form itself around a core of ‘men of substance and established high position socially,’ in the words of founder Frederick Law Olmsted. It was ironic that Olmsted should designate himself spokesman for the city’s native aristocracy — he and his co-founder Henry Whitney Bellows were New Englanders who arrived in New York in the late thirties and early forties…..But there was indeed a cluster of long-established ‘leading merchants,’ as George Templeton Strong called them, who helped bring the Union League Club into being. The shipping merchant Robert Bowne Minturn and tea merchant George Griswold whom Strong repeatedly described as the socioeconomic nucleus of the Club were active members. Minturn was the Club’s first president. The Minturn and Griswold families had been prominent in New York City commerce since the eighteenth century, as had those of members William H. Aspinwall, John Austin Stevens, and future Club president John Jay.” Bernstein argued that the new organization was a deliberate counterpoint to the lawyers and businessmen in the “Belmont Circle” around Democratic National Chairman August Belmont.33 before the war, New York had been closely linked financially to the South – at least through the bankers who provided credit for cotton growers.

The Union League was speedily established in early 1863 with an initial headquarters at 26 East 17th Street at Broadway, facing Union Square. Civic activist George Templeton Strong wrote in his diary in mid-February: “I went to a meeting at Charles Butler’s, 15 East Fourteenth Street, to organize a Loyal Publication Association, in opposition to the surreptitious workings of the gang of Belmonts and Barlows and Tildens that met the other evening at Delmonico’s and were undermined, caught, and haled out into the light by the Post of Friday or Saturday evening.”34 At that meeting, the formation of a Union League was also discussed. Two days later, Strong wrote: “Wealthy shipping merchant “R[obert] B. Minturn called this morning, about the nascent ‘Union League.’ Long talk with him; he is an excellent man, but impracticable and timid. He sees this movement may possibly prove important and wants to be in it, but objects to ‘signing pledges,’ thinks we ought to be liberal and admit weak-backed and coldblooded men to brotherhood with a view to their invigoration and conversion, and wants to confer with W.H. Aspinwall and Hamilton Fish.”35

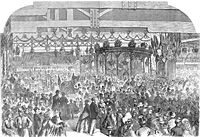

The League organizers made quick progress. Diarist Strong wrote on May 12, 1863: “The Union League Club House was thrown open tonight — ‘inaugurated,’ as the newspapers say. Each of our three hundred and fifty members had three tickets and there were invited guests beside, General [John E.]Wool and his staff, Dr. Vinton, and others. The house was very fairly filled, and was very appropriately and prettily decorated for the occasion under Richard Hunt’s artistic supervision. The assemblage was made up of nice people and included many very nice and pretty women. Several persons said it was ‘brilliant,’ but I do not precisely know what they meant. Ellie enjoyed the evening hugely. Our president, [R. B.] Minturn, made a little speech and introduced successively George Bancroft and Dr. Bellows, who made each a good and effective fifteen minute oration. The performance was decidedly successful. Only two Copperheads got in, to my knowledge, Ned Bell and W.H. Appleton, the bookseller….”36

Strong concluded: “Though this organization is not yet beyond a nascent state and has all the perils of infancy to encounter, it seems a promising Baby. If it thrive and grow, it will be useful. But much perseverance in hard work is still necessary to establish it the position which it aims to occupy. And there are loyal gentlemen in New York who ought to be with us, but are not; for example, Charles E. Strong and George C. Anthon both criticizing twopenny details, and blind, willfully blind, to the importance of the work.37

Given the strong Republican connections of Union League, it was not unexpected that it clashed with Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour, who opposed recruitment of black military units. Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell noted that the Union League “asked Seymour for permission to recruit a negro regiment in New York, but the governor refused the request. The club promptly appealed directly to Secretary Stanton, who was glad to give the members what they asked for. The regiment was raised, and eighteen thousand dollars were collected for its expenses. In due course the negro soldiers were paraded on Broadway and marched off to the front in January, 1864. Edward Channing called attention to the painful practice of rounding up black men as a means of filling quotas after the signing of the Enrollment Act on March 3, 1863. There is no reason to suppose that the ladies who presented the colors to that regiment and the gentlemen who paid its bills did not know that every negro in it counted to the credit of the quota of the state at Washington and diminished the drain on white men by just so much.”38

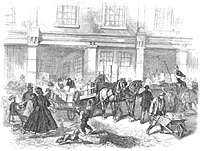

The 20th Regiment received its colors as a Union Square ceremony on March 5, 1864. Historian Iver Bernsteinn observed: “The discipline and loyalty of the Club’s new black regiment was thus for many merchants a vindication of the patrician outlook. The Union Leaguers did not completely discard paternalism but merely changed the color of its clientele. Through a paternalist cultivation of black ‘vrais ouvriers,’ the Union League Club sought to prove to Young America critics that an American working class could become a full partner in the new Christian state.”39 According to historian Paula Baker: “As a contrast to the immigrant working class, some Union League members acclaimed African Americans as models of patriotism and hard work. Inevitably, the league’s championing of African Americans further aroused the suspicions of much of the white working classes toward the organization and its agenda.”40 The league’s concerns with African-Americans took on a particular urgency in July 1863 after the Draft Riots split the city.

“The movement to aid black riot victims began,” according to historian Iver Bernstein, “at the urging of Times editor Henry Raymond and through the informal charity of the Protestant clergy and merchant families who protected black domestic servants. At the end of the riot week, a committee was formed under Union League Club officer Jonathan Sturges to open a subscription list to aid the devastated black community. Over one hundred merchants met to begin distributing relief to black victims, assisting blacks in making claims against the city, and protecting those driven from their homes and jobs. Over the next month and a half the ‘Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People’ paid out almost $40,000 to nearly 2500 black claimants. Most of the money was administered under the supervision of black clergymen, with some assistance from the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor.”41

Like businessmen, clergy were drawn to the civic and political work of the Civil War. Like businessmen, their ministries extended to diplomacy as well. Dr. Henry Bellows did his in Washington. Roman Catholic Archbishop John Hughes did his in France, Italy and Ireland — and the steps of his residence in 1863. Brooklyn’s Henry Ward Beecher did his in England in 1863. Along with Bishop Matthew Simpson, the New York trio probably ranked as the North’s most prominent clergymen in the Civil War.

All this work was done under the shadow of a horrific war. But noted the authors of A History of New York State, “The Civil War affected the religious, political and economic life of New York in many ways, disorganizing many social institutions. In general, the humanitarian movement lost in scope as most reformers concentrated all their energies on the war and on emancipation of the slaves.”42 Care of returning soldiers was an important mission of the civic groups that grew up in New York. At the Soldiers’ Depot in lower Manhattan, soldiers got food and shelter as well as recreation. A supply depot for goods needed by the commission was set up near Union square.

President Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 evoked fulsome eulogies from New York pulpits. At the Episcopalian St. Paul’s Church, Dr. John McClintock said: “All over the world men will weep the death of Mr. Lincoln. Why? Because of the grandeur of his intellect? No! No! And yet the speaker has no sympathy with much that was said about his intellect; possibly it might in some degree be lost sight of in the ineffable sublimity of that moral power which overshadowed all, but of the intellectual power he had a great deal.” Dr. McClintock continued: “Yet it was not for the intellect but for the moral qualities of the man that we loved him. It is a wise order of Providence that it is so that men are drawn. WE never love cold intellect. We may admire it, we may wonder at it, sometimes we may even worship it, but we never love it. The hearts of men leap out only after the image of god in man and the image of God is love.”43

In Brooklyn, Rev. William Ives Buddington preached at the Clinton Avenue Congregational Church: “There are times when the death of a good man will do more than his life. Suffering wrong with patient love will sometimes triumph when everything else fails. God needed for his purposes the death of his Son, so imperatively needed it that not even the prayer of that Son, so imperatively needed it that not even the prayer of that Son. Whom his Father had always heard, could avail to make the cup pass from him. God needed the blood of martyrs in their day to corroborate and sanctify His gospel. God needed likewise the blood of Abraham Lincoln. We can see already that it is doing what his life and best services were powerless to accomplish.”44

Footnotes

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 423-424.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 153.

- Joseph R. Howard, Life of Henry Ward Beecher: The Eminent Pulpit and Platform Orator, p. 437-438.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 155.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 155.

- In Memoriam, Henry Whitney Bellows, D.D., G.P. Putnam’s New York, April 13, 1882, p. 24 (William E. Dodge, Jr.).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. xxxvii.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, First Supplement, p. 76-77 (June 9, 1861).

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1909, p. 373.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 159.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 212.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 604 (Letter from George Templeton Strong to Francis Lieber, July 12, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 196 (December 14, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 197 (December 19, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 226 (May 15, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 204-205 (January 29, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 207 (February 18, 1862).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 247.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 215.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 218 (April 19, 1862).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 215.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 306 (March 17, 1863).

- Walter D. Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows, p. 238-239.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 165 (July 15, 1861).

- Milton M. Klein, editor, The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 432 (Paula Baker, “New York during the Civil War and Reconstruction”).

- In Memoriam, Henry Whitney Bellows, D.D., G.P. Putnam’s New York, April 13, 1882, p. 24 (William E. Dodge, Jr.).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 213-214.

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1909, p. 379.

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 342.

- John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans, p. 275.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 286.

- Milton M. Klein, editor, The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 434 (Paula Baker, “New York during the Civil War and Reconstruction”).

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 129-130.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 297 (February 14, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 299 (February 16, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 321 (May 12, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 321 (May 12, 1863).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 300.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 160.

- Milton M. Klein, editor, The Empire State: A History of New York, p. 434 (Paula Baker, “New York during the Civil War and Reconstruction”).

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, p. 56.

- David M. Ellis, Jams A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 343.

- Morgan Dix, “The Death of President Lincoln, April 19, 1865 (Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1865). .

- Lloyd Lewis, Myths After Lincoln, p. 100..