New York City and New York State played an important role in Mr. Lincoln’s accession to the Presidency and in his performance as President. But New York City was also a center of anti-Lincoln fervent and anti-slavery agitation during the Civil War. In the 1860 and 1864, the Republican ticket was trounced in New York City — although Republican sentiment elsewhere in the state gave Mr. Lincoln majorities in 1860 and 1864.

In 1860, New York City’s mercantile interests combined with the Democratic sentiments of the city’s many immigrants, especially Irish-Americans. Both groups were pro-Southern and some pro-slavery. “The secession crisis was reflected in a business panic,” wrote historian James A. Rawley. “The stock market fell, New York merchants found difficulty in collecting bills in the South, and gold began to flow to Southern ports. It was estimated that $3,500,00 in gold moved in ten days. New Yorkers engaged in Southern trade feared debt repudiation; by November 14 panic had set in and business failures began.”1 The fears of the less affluent were also economic but more racist. Historian Leslie M. Harris noted: “From the time of Lincoln’s election in 1860, the Democratic Party had warned New York’s Irish and German residents to prepare for the emancipation of slaves and the resultant labor competition when southern blacks would supposedly flee North.” 2

Governor Morgan wrote President-elect Lincoln on November 20: “Since the gratifying result of our Presidential contest we at the State Capital have been busy in watching the progress of the severe money panic in New York, which has been brought about by madness North and South. It has been severe, the depreciation in stocks large. The Banks and business men have been panic struck. I am of the opinion that the crisis has passed, that yesterday was ‘blue Monday in New York and the hardest day we shall have in 1860.'”3

The mood in New York City was more sympathetic to the South than in much of the rest of the North. Historian Seymour Mitchell noted: “The first ordinance of secession was passed on December 20, 1860. In the meantime the city of New York took alarm. Men who had supported the fusion electoral ticket against Lincoln felt that some expression of opinion from the North might avert or delay any action in South Carolina. Conservative citizens signed the resolutions which led to what is called the Pine Street Meeting on December 16. Charles O’Conor presided, and ten days later John A. Dix wrote Seymour that the committee appointed at the meeting ‘are very desirous that you should go to Washington with some other gentlemen, and if necessary to the South to induce if possible, our southern friends to pause in their secession movement til we can do something to restore harmony.” There is no evidence to show whether or not Seymour ever sent Dix the telegram for which he was asked.”4

New York’s initial political response to the Confederate secession was mixed — mixed up as it was with New York’s commercial interests. Historian John William Leonard wrote about how conservative Democrats reacted to the rebellion:

After South Carolina had declared itself out of the Union, conservative opinion in New York was divided,” wrote historian John William Leonard. “At one extreme were those who contemplated as a possibility that New York should become a free city, entirely independent of the State or National government, and in a position to maintain a policy of absolute neutrality in the event of the breaking up of the Union. These were represented by the mayor, Fernando Wood, who actually advocated that course in his message to the Common Council, January 7, 1861.There was another conservative wing, whose members still hoped to bring about a peaceful solution of the pending problems, and whose last effort was voiced in what became known as the Pine Street Meeting, held December 15, 1860. Among its promoters were leading citizens of New York: Charles O’Connor (who presided), John A. Dix, Samuel J. Tilden, William B. Astor, James W. Beekman, Edward Cooper, and many others. The meeting was largely attended, and resolutions were addressed to the people of the South, fraternal and conciliatory in tone, but firm in Union sentiment, as coming from men who had heretofore been known as friends of the South, and had voted with the Southern people upon matters involving Southern interests. A committee, headed by ex-President Millard Fillmore, was appointed, was appointed to present the resolutions to Jefferson Davis, and to the governors of South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama.5

On the Republican side, there were also disagreements. Prominent Republican conservatives — including many in business like Moses S. Grinnell — wrote President Lincoln at the end of January 1861 urging him to come to a compromise with the South:

Many of those who voted with the Republican party at the late election did so with no view of pronouncing definitely upon the question of Slavery in the territories; they were disgusted with the abuses which had grown up with the party which had for so many years been dominant and desired a change. Having confidence in your integrity and Statesmanship they cast their votes for you. This class of men shudder at the thought of risking the advantages of the Union, in all its integrity, on the territorial question.To show you how unimportant comparatively this point is considered in this State we hazard nothing in saying that if the question could to day be fairly submitted to the people of the city of New York upon a partition of the Territories at present belonging to the United States on the line proposed by the so called Crittenden compromise the vote against it would be less than Ten thousand while our vote in November was thirty three thousand and in the State, this compromise would be supported in our judgment, by a vote of over four hundred thousand.6

Many of these businessmen were allied with Senator William H. Seward, the retiring New York Senator who was slated to be Mr. Lincoln’s Secretary of State. Seward tried during the early weeks of 1861 to reconcile the South to the North. “If Seward should get his way, the new government would deal with secession a manner far less firm and forceful than Lincoln was thinking of,” wrote historian Richard N. Current. “Secession he considered a kind of insanity that was soon to pass. ‘The question then is, what in these times — when people are laboring under the delusion that they are going out of the Union and going to set up for themselves — ought we to do in order to hold them in?’ The answer, Seward thought, was to follow the example of every good father in dealing with sulky members of his family. ‘That is, be patient, kind, paternal forbearing and wait until they come to reflect for themselves.'”7

This delusion of forbearance evaporated with the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. New York immediately rallied behind the Union cause. With the attack on Fort Sumter, even Democrats changed their political tune. New York attorney George Templeton Strong wrote in his diary two days after the assault: “From all I can learn, the effect of this on Democrats, heretofore Southern and quasi-treasonable in their talk, has fully justified the sacrifice. I hear of F. B. Cutting and Walter Cutting, [Abram S.] Hewitt, Lewis Rutherfurd, Judge [Aaron] Vanderpoel, and others of that type denouncing rebellion and declaring themselves ready to go all lengths in upholding government. If this class of men has been secured and converted to loyalty, the gain to the country is worth ten Sumters.”8

Two prominent Republican businessmen telegraphed President Lincoln on April 15: “Nothing can exceed the enthusiasm. A large meeting of men of both parties is to be held at two o’clock, at [Simeon] Draper’s office to respond to the Proclamation.”9 Draper was the Republican state chairman as well as a New York City businessman. Indeed, nothing united New York like the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett changed his pro-Southern tune. Even New York City Mayor Fernando Wood took up the Union cause — albeit under duress. “New Yorkers were ready to take up the gage of battle,” wrote historians David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman in A History of New York State.10

Patriotism sprouted virtually everywhere. “The series of great meetings held throughout the State testified to the fact that, for a while at least, party strife and recrimination were stilled,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “In the days immediately following the firing upon Fort Sumter thousands of Democrats, who subsequently refused to lay aside their party, united the Republicans in a noble demonstration in support of the administration. Perhaps some politicians were insincere and were swept along. The masses, however, were actuated by patriotic motives. In these meetings, Republicans, Douglas Democrats, Breckinridge Democrats, Tammany men, Mozart men, and Bell-Everttites all joined.”11

Governor Edwin D. Morgan appointed a special commission — of Richard M. Blatchford, William M. Evarts, Moses Grinnell and his cousin George D. Morgan — to work with the Lincoln Administration to recruit and supply troops. The New York State Legislature met on the Sunday after the bombardment and passed legislation to deal with the crisis. “A conference of the important state officials and the military and financial committees of both houses of the Legislature was immediately held at the Governor’s mansion,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “A committee of those present drew up a bill authorizing the Governor to enroll for two years thirty thousand volunteers, appropriating three million dollars, and providing a tax for these purposes. The bill was printed on the night of the 14th; and on the next day, with a provision establishing a state military board composed of the governor, lieutenant-governor, secretary of state, comptroller, and attorney-general, the measure was introduced, put through all stages, and passed in both houses.”12

Union fervor gripped Democrats as well as Republicans. “Bombardment of Fort Sumter obscured all minor issues in civil war. If New York had been loath to antagonize the South before Sumter, such a wave of patriotism now engulfed the State as to submerge these feelings for a time,” wrote historian James A. Rawley. “The war could not conceivably be long or costly. An easy victory for the Union cause, attended by martial glory and high adventure, invited participation by all spirited young men. Throughout the State patriotic meetings were held — Democrats joining in common cause with Republicans. From New York, center of pro-Southern sentiment, Moses Grinnell wired [Governor Edwin D.] Morgan: ‘The Legislature should take prompt action appropriate five millions & call for one hundred thousand men. This is the universal sentiment in the city.'”13

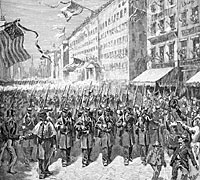

Historian John William Leonard wrote: “The Legislature appropriated $3,000,000; the New York City militia regiments volunteered; recruiting of new volunteer regiments rapidly went on, and the Common Council at once appropriated $1,000,000 for military equipment and outfit, for which $1,000,000 of Union Defense Fund Bonds were issued. The march of the New England troops through the city, April 18th, en route to Washington was an ovation of the most emphatic kind, the entire marching route being lined with dense masses of the people, shouting their joy with deafening cheer. The news later.”14

In Albany, the State Legislature was in session and went to work immediately to meet the crisis. Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “The attitude of the Democratic members, who but recently had opposed with practical unanimity the five hundred thousand dollars appropriation, showed how the news of Sumter’s fall broke down party lines, shattered the united front of the Democracy, and overthrew the platform formulated by the late Democratic convention [in February].”15

Wisconsin Republican leader Carl Schurz came to New York to raise a regiment of cavalry. He recalled in his memoirs:

I found the people of New York in the full blaze of the patriotic emotions excited by the firing upon Fort Sumter and the president’s call for volunteers. There were recruiting stations in all parts of the town. The formation of regiments proceeded rapidly. Wealthy merchants were vying with each other in lavish contributions of money for the fitting out of troops, and numberless women of all classes of society were busy stitching garments or bandages for the soldiers, or embroidering standards. There was hardly anything else talked about in public places, in the clubs, and in family circles. The whole town constantly resounded with patriotic speeches and martial music. Party spirit seemed to be fairly lifted off its feet by the national enthusiasm. Men who but yesterday had cursed every Republican as a ‘rank abolitionist’ and every abolitionist as an enemy of the country, and who had vociferously vowed that no armed body of men should be permitted to pass through the City of New York for the purpose of ‘making war upon a sovereign State,’ now, like Daniel E. Sickles in the East, and John A. Logan in the West, rushed to arms themselves.16

Tammany historian Jerome Mushkat wrote: “The attack on Fort Sumter changed the political game, but not its rules. In the first surge of patriotism, Tammany and the New Regency momentarily forgot party lines and joined the Republicans to form a solid front against the Confederacy. The General Committee and the Tammany Society formed a regiment, Grand Sachem William Kennedy volunteered to become its commanding officer, and they all dedicated themselves to fight for ‘democratic institutions and constitutional liberties.'”17

The martical spirit seemed infectious. Even cautious attorney George Templeton Strong got caught up in the fever: “Our ‘New York Rifles’ met at 7:30 at rooms hired for the evening, a loft at 814 Broadway. It was crowded, so two squads adjourned to the old club house at the corner of Astor Place, where we were drilled more than two hours. Everybody awkward, but earnest and diligent. Then we marched back. I was solemnly elected president of the association till our military commandant shall be chosen, and got through my duties decently well, I believe, keeping the mob of men in tolerable order, though all were on their feet, having nothing but the floor to sit on.”18

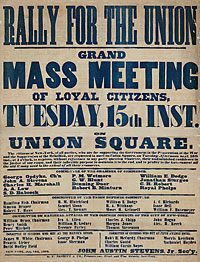

About a week after the surrender of Fort Sumter, a Saturday mass meeting was held in Union Square for an estimated 100,000 New Yorkers. Historian David Sidney Brummer wrote: “On Monday, the 15th of April, a number of prominent gentlemen held a preliminary conference. As a result of this and subsequent consultations, the citizens ‘without regard to previous political opinions’ were called upon to assemble at Union Square on the following Saturday at three o’clock, ‘to express their sentiment in the present crisis in our national affairs and their determination to upheld the government of their country and maintain the authority of its constitution and its laws.’ It also recommended that all places of business be closed at two o’clock.”19

Democrat John A. Dix, who had been Secretary of the Treasury for the last months of the Buchanan Administration, presided over the bipartisan gathering. Among the many politicians who spoke were Oregon Senator Edward D. Baker and former New York Senator Daniel S. Dickinson — along with businessman Simeon Draper and industrialist Peter Cooper. Soldiers who had defended Fort Sumter were present for the rally — along with politicians of all partisan stripes. Former Whig Governor Hamilton Fish said: “Thank God, I look now upon a multitude that knows no party divisions — no Whigs, no Democrats or Republicans.”20

John Jacob “Astor, [Cornelius] Vanderbilt, [William H.] Aspinwall, A.T. Stewart, [August] Belmont of the House of Rothschild, the millionaires who had been at the breakfast to Lincoln when he came through New York, they and their cohorts and lawyers were now for war,” wrote Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg.21 Even Mayor Fernando Wood was called upon to speak at the April 20 meeting — although he was apparently warned by [John A.] Dix that he better voice Union sentiments, not his usual pro-Southern rhetoric. The Herald reported that Wood said “he cared not what past political association might be severed. He was willing to give up all sympathies, and, if they pleased, all errors of judgment upon all national questions.”22 Attorney George Templeton Strong described the event in his diary:

Walked uptown at two. Broadway crowded and more crowded as one approached Union Square. Large companies of recruits in citizen’s dress parading up and down, cheered and cheering. Small mobs round the headquarters of the regiments that are going to Washington, starting at the sentinel on duty. Every other man, woman, and child bearing a flag or decorated with a cockade. Flags from almost every building. The city seems to have gone suddenly wild and crazy.The Union mass-meeting was an event. Few assemblages have equalled in it numbers and unanimity. Tonight’s extra says there were 250,000 present. That must be an exaggeration. But the multitude was enormous. All the area bounded by Fourteenth and Seventeenth Streets, Broadway and Fourth Avenue, was filled. In many places it was densely packed, and nowhere could one push his way without difficulty. This great amoeba (to speak microscopically) sent off its peudoods far down Broadway and Fourteenth Street and in every cross street. There were several stands for orators, and scores of little speechifying ganglia besides, from carts, windows, and front stoops. Anderson appeared and was greeted with roars that were tremendous to hear. The crowd, or some of them, and the ladies and gentlemen who occupied the windows and lined the housetops all round Union Square, sang ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ and the people generally hurrahed a voluntary after each verse.Mayor Wood, the sagacious scoundrel, committed himself by a straightforward speech. Reverend old Gardiner Spring, who opened one of the many centres of the meeting ‘with prayer,’ came out soundly and manfully in a little introductory allocution [sic]. In substance: ‘Many of you know my opinion about issues heretofore existing between the North and South. That opinion is unchanged. But the controversy is now between Government and Anarchy, Law and Rebellion.”23

Mobilization and recruiting went forward quickly. “Within a week the Seventh Regiment was on its way to the national capital, and four more states — Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia — seceded. On April 20 Major Robert Anderson, who had commanded the forces at Fort Sumter, arrived in New York City, and the occasion was marked by a stupendous demonstration. By July almost forty-seven thousand New Yorkers had enlisted for service in defense of the Union.” wrote the authors of A History of New York State.24

Union fervor swept up the city. “The overwhelming response to the speeches resulted in the appointment of a Union Defense Committee,” wrote Chester L. Barrows, biographer of William M. Evarts. The 21- member committee was headed by Democratic politician John A. Dix, chairman (soon succeeded by Hamilton Fish); Simeon Draper, vice chairman; attorney William M. Evarts, secretary; and Theodore Dehon, treasurer. It included John J. Cisco, Alexander Stewart, James S. Wadsworth, Moses H. Grinnell, and Edwards Pierrepont. Barrows wrote: “Its first meeting on the twenty-second, appointed a Committee of Correspondence, including Evarts, Fish, Pierrepont, and Cisco, to communicate with federal and state authorities. The Union Defense Committee was essentially an emergency organization to hurry troops and supplies to the battle area.”25

In the rush to respond, New Yorkers ran into a thicket of conflicting responsibilities, demands, duties, and authority. Dix quickly moved from one responsibility to another. “In his requisition of April 15, 1861, Cameron had authorized two major generals of militia for New York. Governor Morgan assigned John A. Dix and James Wadsworth to command volunteer organizations. The War Department refused to recognize Morgan’s authority to make the appointments. The difference between the State and Federal governments lay in theory, Morgan looking upon New York’s troops as militia being called into Federal service, Cameron holding them to be volunteers going directly into Federal service, bypassing a militia phase.”26 Eventually the impasse was resolved when President Lincoln appointed both Dix and Wadsworth as major generals. In order to enhance Governor Morgan’s authority in New York State, Morgan was appointed a major general by President Lincoln as well in September 1861.

According to historian Daniel Van Pelt, the Union Defense Committee’s “duties, as defined by the resolutions adopted at the Union Square mass meeting, were to collect funds and to aid or promote the movements of the Government so much as possible. To facilitate these objects and receive subscriptions, it sat at the house in Pine Street during the day, and at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in the evening. As a result of these efforts to raise money the gratifying statement is made that in the course of three months New York City alone raised $150,000,000 in aid of the Government.”27 According to historian John William Leonard, “It raised funds for arming, equipping and transporting troops, and did a vast number of things quickly, which the municipality could only have accomplished very slowly. It continued in operation for a year and before its final adjournment, April 30, 1862, had disbursed more than $1,000,000 for the benefit of New York volunteers, their widows and orphans.”28

These and other Union efforts in New York City were rallied by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, who had been at his home in Maine when the Civil War broke out. He soon left for New York City, where he had been urged to go to organize Union efforts and to be close to Washington in case something happened to President Lincoln. Hamlin biographer Mark Scroggins wrote: “Hamlin worked closely with the Union Defence Committee which had been organized to raise money for the Union cause. Hamlin also assisted major general John E. Wool. Despite the tremor in his hands and a tendency to repeat things he had said only a few minutes before, the seventy-seven year old General was a splendid military organizer. Upon his arrival in New York City on April 22, Wool worked tirelessly from his rooms at the St. Nicholas Hotel. The old general arranged for transportation and rations for soldiers bound for Washington, he chartered steamers and transports for troops, and he sent provisions to reinforce Fort Monroe. He also worked with John A. Dix, chairman of the Union Defense Committee, on a plan to relieve Washington. The committee (and Hamlin) commended Wool for his energy and ability and on April 31, passed a resolution praising his efforts.29

On April 26, 1861, Seward wrote his friend, Republican boss Thurlow Weed: “A week ago the [Union Defense] committee came here to offer and urge upon its fourteen regiments. It was agreed and ordered by the President and Secretary of War. We pray night and day for troops. New York neither sends nor lets us draw them from elsewhere. The Governor appealed from the President’s orders. The committee appealed to him, whereat he telegraphed both the Governor and the committee to come. Neither comes. How am I to reconcile? I don’t know the grounds or merits of the controversy, nor at what hazard I intervene. You ought to be able to reconcile the parties, for you are near both of them.”30

By the end of May 1861, New York had raised 30,000 men for the war effort. One of the first regiments was the New York Zouaves, led by President Lincoln’s young friend, Elmer E. Ellsworth. He was a New York State native from Mechanicsville who had moved to Illinois to earn his fortune. Attorney George Templeton Strong wrote in his diary: “On my way uptown saw the ‘Fire Brigade of Zouaves’ on their march to the steamer, escorted by the whole fire department. This is Colonel [Elmer] Ellsworth’s regiment, about 1,100 strong, armed with Sharp’s rifles and revolvers. They are a rugged set, a little above Bill Wilson’s corps in social status, generally men and boys who belong to target companies and are great in a plug-muss. They were coming down Chatham Street and hurrying up Broadway. At the Astor House they halted and received a flag. Mr. J. J. Astor had presented with another. I got on top of an omnibus and inspected them. The crowd was immense and the cheering uproarious. These young fellows march badly, but they will fight hard if judiciously handled. As a regiment of the line, they will be weak, but they are the very men to deal with the mob of Baltimore.”31

Strong reported how news of Ellsworth’s murder five days later was received in New York City: “A large force marched from Washington last night, secured Arlington Heights, and pushed on to Alexandria, which was occupied without serious resistance. Colonel Ellsworth’s Regiment of Firemen Zouaves headed the column. Ellsworth entered the principal hotel of the place, the ‘Marshall House,’ and himself hauled down the rebel flag flying over it, and was thereupon or soon thereafter shot by a concealed assassin, said to have been one Jackson the hotel-keeper. That flower of Sepoy chivalry was promptly knocked on the head. Colonel Ellsworth was a valuable man, but he could hardly have done such service as his assassin has rendered the country. His murder will stir the fire in every western state, and shows all Christendom with what kind of enemy we are contending.”32

Two days later, Strong wrote: “Today’s event was Colonel Ellsworth’s funeral; attended, I hear by a vast, grim, silent crowd. Beside the driver of the hearse sat Private Brownell of Ellsworth’s regiment (who shot down and bayonetted his commandant’s assassin), bearing his rifle with fixed bayonet and the rebel flag which Ellsworth had hauled down. This close juxtaposition of the murdered colonel with the bayonet that was red with his murderer’s lifeblood forty-eight hours ago was hardly appropriate to the solemn decencies of a funeral, but certainly picturesque and significant — a stern symbol of the feeling that begins to prevail from Maine to Minnesota.”33 Leo Hershkowitz wrote in Tweed’s New York that Ellsworth’s murder spurred recruitment and sympathy: “Money was raised to aid his parents and the body was brought to New York and a fine public funeral was held on May 26. Among the pallbearers was a large group of Fire Department officials including William Tweed, who had been named one of the Department commissioners effective as of May 28. Proclamations of sympathy were given by the council, as well as by public and private organizations. The death of Ellsworth underlined the ‘treachery’ of the South and hardened the resolve for the national cause.”34

George Templeton Strong did not wholly approve the job the committee did, recording in his diary on July 12, 1861: “This evening Mr. Ruggles, the Rev. Dr. Weston, George Allen, and half a dozen others met here to consider about organizing an association or committee to help the government provide for the material wants of the New York regiments at Old Point Comfort and elsewhere. We organized ourselves, and with some little prospect of doing good service. There is much money here that is impatient to burst out of private pockets into the hands of any honest body of trustees for the public good. But [Simeon] Draper & Co. have made the ‘Union Defense Committee’ to stink in the nostrils of all good citizens.”35

The process of recruiting, equipping and sending troops to the war front near Washington was complicated. New York raised too many troops — through too many authorities including the Governor, the Union Defence Committee and individuals such as Democratic Congressman Daniel J. Sickles. Governor Morgan alone sent 38 regiments to Washington by July 12. “The Military Board and the extreme confusion and inefficiency in Washington would seem to be sufficient handicaps to a ‘commander-in-chief.’ The Union Defence Committee, formed by patriotic citizens in New York City, became another impediment, vexing because it was so well-intentioned, yet at variance with the constitutional role of the governor,” wrote historian James A. Rawley. “A delegation from the Committee visited Lincoln, to whom it represented its desire to provide troops and the dissatisfaction in New York City with Washington’s sluggish acceptance of troops. Lincoln agreed to accept 14 regiments from the New Yorkers, who rode home gleefully in a special train provided by the Secretary of War.”36

New York always required a disproportionate amount of President Lincoln’s attention. Its large population was matched by the number of political disputes that Lincoln was required to handle. “The contributions of the Empire State to the war effort were massive and impressive. New York States was the leading state in population and wealth, and New York, provided the greatest number of soldiers, the great quantity of supplies, and the largest amount of money. In addition, New York’s citizens paid the most taxes, bought the great number of war bonds, and gave the most to relief organizations. Enlistment bounties alone cost the state over $43,000,000,” wrote David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman in A History of New York State.37

The authors wrote: “On the battlefields as well, citizens of New York distinguished themselves. More than forty generals hailed from New York, some in posts of great responsibility. The United States Navy naturally attracted many volunteers from the ocean and lake marine. Captain John Worden was in command of the Monitor, which sailed from Brooklyn to the famous engagement with the Merrimac. Altogether, New York sent 464,701 men into the army. Deaths, counting those who died after discharge from maladies contracted in the service, exceeded fifty thousand. These losses hit every section and every class in the state. The cities quickly recouped their population losses through immigration from Europe and from the countryside, but the towns, villages, and farms of New York recovered slowly from the blows of the war.”38

Panic, unfortunately, was sometimes mixed with patriotism in New York. Receiving visiting delegations was an occupational hazard of being President. For Mr. Lincoln, the hazards began even before he took the oath of office. According to Lucis E. Chittenden, a Vermonter who later became an official of the Treasury Department, there was a memorable exchange between President-elect Lincoln and New York representatives to the Peace Conference at the Willard Hotel.

It was reserved for the delegation from New York to call out from Mr. Lincoln his first expression touching the great controversy of the hour. He exchanged remarks with ex-Governor [John A.] King, Judge [Amaziah B.] James, William Curtis Noyes, and Francis Granger. William E. Dodge had stood, awaiting his turn. As soon as his opportunity came, he raised his voice enough to be heard by all present, and, addressing Mr. Lincoln, declared that the whole country in great anxiety was awaiting his inaugural address, and then added: ‘It is for you, sir, to say whether the whole nation shall be plunged into bankruptcy; whether the grass shall grow in the streets of our commercial cities.’“Then I say it shall not,” he answered, with a merry twinkle of his eye. “If it depends upon me, the grass will not grow anywhere except in the fields and the meadows.”“Then you will yield to the just demands of the South. You will leave her to control her own institutions. You will admit slave states into the Union on the same conditions as free states. You will not go to war on account of slavery!”A sad but stern expression over Mr. Lincoln’s face. ‘I do not know that I understand your meaning, Mr. Dodge,” he said, without raising his voice, ‘Nor do I know what my acts or my opinions may be in the future, beyond this. If I shall ever come to the great office of President of the United States. I shall take an oath. I shall swear that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, of all the United States, and that I will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. This is a great and solemn duty. With the support of the people and the assistance of the Almighty I shall undertake to perform it. I have full faith that I shall perform it. It is not the Constitution as I would like to have it, but as it is, that is to be defended. The Constitution will not be preserved and defended until it is enforced and obeyed in every part of every one of the United States. It must be so respected, obeyed, enforced, and defended, let the grass grow where it may.’Not a word or a whisper broke the silence…Mr. Dodge attempted no reply…Some of the more ardent Southerners silently left the room….For the more conservative Southern delegates, the statesmen, Mr. Lincoln seemed to offer an attraction. They remained until he finally retired.39

Two months later, after Fort Sumter had been attacked and New York troops arrived in the Capital to help protect it from Confederate forces, presidential aide John G. Nicolay wrote in his diary: “We (I mean the President and four of five others of us from the White House) spent a very agreeable afternoon from about 3 to 6 o’clock P.M. yesterday. The 71st Regiment New York Volunteers are quartered at the Navy Yard, and having several good musicians in the ranks, and a fine regimental band, by way of pastime improved a regular concert…in one of the large storerooms in the Navy Yard, which they occupy as barracks. They had an elegant audience of some two or three hundred invited guests, and make the enterprise a great success.” He added that they later “saw the 71st Regiment on ‘dress parade,’ and then went home.” 40

Artist Francis B. Carpenter wrote: “Among the numerous delegations which thronged Washington in the early part of the war was one from New York, which urged very strenuously the sending of a fleet to the southern cities, — Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah, — with the object of drawing off the rebel army from Washington. Mr. Lincoln said the project reminded him of the case of a girl in New Salem, who was greatly troubled with a ‘singing’ in her head. Various remedies were suggested by the neighbors, but nothing tried afforded any relief. At last a man came along, — ‘a common-sense sort of man,’ said he, inclining his head towards the gentleman complimentarily, — ‘who was asked to prescribed for the difficulty. After due inquiry and examination, he said the cure was very simple. ‘What is it?’ was the anxious question. ‘Make a plaster of psalm-tunes, and apply to her feet, and draw the ‘singing’ down,’ was the rejoinder.”41

New York even played a role in the revitalization of the Navy. Its leaders were particularly concerned about the port’s safety. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote about New York’s reaction to the Merrimack‘s sinking of Union ships in Virginia in March 1862 — as the Lincoln Cabinet met to consider its options:

Mr. [Salmon P.] Chase approved the suggestion, but thought it might be well to telegraph Governor [Edwin D.] Morgan and Mayor [George] Opdyke, at New York, that they might be on their guard. Stanton said he should warn the authorities in all chief cities. I questioned the propriety of sending abroad panic missives, or adding to the alarm that would naturally be felt, and said it was doubtful whether the vessel, so cut down and loaded with armor, would venture outside of the Capes; certainly, she could not, with her draught of water, get into the sounds of North Carolina to disturb Burnside and our forces there; nor was she omnipresent, to make general destruction at New York, Boston, Port Royal, etc., at the same time; that there would be general alarm created; and repeated that my dependence was on the ‘Monitor,’ and my confidence in her great. ‘What,’ asked Stanton, ‘is the size and strength of this ‘Monitor?’ How many guns does she carry?’ What I replied two, but of large calibre, he turned away with a look of mingled amazement, contempt, and distress, that was painfully ludicrous. Mr. Seward said that my remark concerning the draught of water which the “Merrimac’ drew, and the assurance that it was impossible for her to get at our forces under Burnside, afforded him the first moment of relief and real comfort he had received. It was his sensitive nature to be easily depressed, but yet to promptly rally and catch at hope. Turning to Stanton, he said we had, perhaps, given away too much to our apprehensions. He saw no alternative but to wait and hear what our new battery might accomplish.“Stanton left abruptly after Seward’s remark. The President ordered his carriage, and went to the Navy Yard to see what might be the views of the naval officers.42

The USS Monitor, built in Brooklyn in less than three months, arrived in time to create a standoff with the Merrimac,, but the worries and dissatisfaction of leading New Yorkers continued. Lincoln biographer Alonzo Rothschild wrote: “Early in September, 1862, a committee of prominent New Yorkers, led by the venerable son of Alexander Hamilton, called upon Mr. Lincoln ostensibly to urge ‘a change of policy.’ They represented, according to their own statement, not only the views of the dissatisfied Republican element in the Empire State, but of five New England Governors as well, The animus of their criticisms soon became apparent to the President, who, in the midst of the heated discussion that ensued, angrily exclaimed: ‘You, gentlemen, to hang Mr. Seward would destroy the government.'”43

In the spring of 1863, New York panicked over the Union defeat at Chancellorsville and the draft quotas imposed on New York. Both Peace Democrats and War Democrats were aroused and held rallies. “New York was aroused by this and other signs of grown Copperheadism. Accordingly, a number of demonstrations were held to disprove any suspicions of New York City’s loyalty and to stir anew the patriotism of the people to meet the back fire.,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer. “At the end of March a great mass-meeting resulted in the formation of a second organization of patriotic citizens, the Loyal National League.”44 It held a mass rally in Union Square on the second anniversary of the bombardment of Fort Sumter. The first such organization, the Loyal Union League, soon held a similar rally at Madison Square. Democrats countered with their own rallies. When Draft riots broke out in July 1863, New Yorkers panicked again.

Less than two years later, New Yorkers celebrated. George Templeton Strong in his diary on April 3, 1865 — after news reached New York of the fall of Richmond to Union troops: “New York has seen no such day in our time nor in the old time before us. The jubilations of the Revolution War and the War of 1812 were those of a second-rate seaport town. This has been metropolitan and worthy an event of the first national important to a continental nation and a cosmopolitan city.” He reported walking down Wall Street when he learned the news. An impromptu rally was organized by Customs Director Simeon Draper at the Custom House: “An enormous crowd soon blocked that part of Wall Street, and speeches began. Draper and the Hon. Moses Odell and [William M.] Evarts and Dean (a proselyte from Copperheadism) and the inevitable [Prosper M] Wetmore, and others, severally had their say, and the meeting organized at about twelve, did not break, I hear, till four P.M. Never before did I hear cheering that came straight from the heart, that was given because people felt relieved by cheering and hallooing. All the cheers I ever listened to were tame in comparison, because seemingly inspired only by a design to shew enthusiasm. The were spontaneous and involuntary and of vast ‘magnetizing’ power. They sang ‘Old Hundred,’ the Doxology, ‘John Brown,’ and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ repeating the last two lines of Key’s song over and over, with a massive roar from the crowd and a unanimous wave of hats at the end of each repetition. I think I shall never lose the impression made by this rude, many-voiced chorale. It seemed a revelation of profound national feeling, underlying all our vulgarisms and corruptions, and vouchsafed to us in their very focus and centre, in Wall Street itself.”45

Footnotes

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 120.

- Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863, p. 279.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 121 (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Abraham Lincoln, November 20, 1860).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 210.

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1909, p. 369.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from New York Republicans to Abraham Lincoln, January 29, 1861).

- Richard N. Current, Lincoln and the First Shot, p. 22-23.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 120 (April 14, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Richard M. Blatchford and Moses H. Grinnell to Abraham Lincoln, April 15, 1861).

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 242.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 143.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 141.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, .

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1900, p. 370.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 141.

- Carl Schurz, The Autobiography of Carl Schurz, p. 174 (Abridgment by Wayne Andrews).

- Jerome Mushkat, Tammany: The Evolution of a Political Machine, 1789-1865, .

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 134 (April 24, 1861).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 144-145.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 146 (New York Herald, April 21, 1861).

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume I, p. 217-218.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 146 (New York Herald, April 21, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 127-128 (April 20, 1861).

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrelt, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 242.

- Chester L. Barrows, William M. Evarts: Lawyer, Diplomat, Statesman, p. 102-103.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 151.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, p. 402.

- John William Leonard, History of the City of New York, 1609-1909, p. 372.

- Mark Scroggins, Hannibal: The Life of Abraham Lincoln’s First Vice President, p. 170.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 333 (Letter from William H. Seward to Thurlow Weed, April 26, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 137 (April 29, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 146 (May 24, 1861).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 147 (May 26, 1861).

- Leo Hershkowitz, Tweed’s New York: Another Look, p. 82.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 158 (June 12, 1861).

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 146-147.

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 338.

- David M. Ellis, James A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 338.

- Lucius E. Chittenden, Recollections of President Lincoln and His Administration, p. 74-75.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 41-42 (May 10, 1861).

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 239.

- Alexander McClure, editor, The Annals of War: Written by Leading Participants North and South, p. 25 (Gideon Welles, ).

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln, Master of Men: A Study in Character, p. 155.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 297-298.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, 574-575, (April 3, 1865).