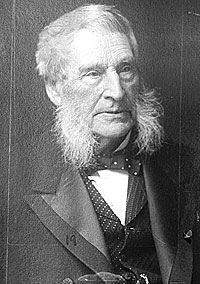

John Bigelow

John Bigelow

John Bigelow was “a gentleman of the highest personal character; a Republican throughout the war and long afterwards, and a man of spotless record,” editorialized the New York Tribune in 1876.1 Bigelow, once a Republican, was the Democratic candidate for Secretary of State in that year. Bigelow’s old paper, the New York Evening Post, editorialized: “Mr. Bigelow’s varied accomplishments, his wide experience in public affairs, his high personal character and his freedom from every sort of ‘entangling alliance’ which so often hampers men of good reputation when they enter into active political life, all mark him as preeminently fitted for the service of the people in a place of great responsibility.”2

Bigelow “was strong-willed, sometimes opinionated. His judgment of men was strongly colored by his personal relations with them. His judgment of institutions was occasionally shadowed by his religious views, most markedly evident in his intolerance of Catholicism. His dedication of himself to the cause of democracy did not prevent him from being, personally, an aristocrat. His shrewd ability to satisfy his modest wants blinded him to the hardships of the less fortunate. Yet with all that, he was a man of singularly balanced qualities of mind and spirit,” wrote biographer Margaret Clapp.3

John Bigelow “was a young man of rare accomplishments,” according to historian Allan Nevins. Bigelow was well-travelled, well-read, and well-cultured, he had special entre among England’s and Frances’ elite. For a dozen years before his diplomatic appointment, Bigelow had served as co-owner and editor of the New York Evening Post with a more famous colleague, poet William Cullen Bryant. Before that, he had been an attorney of uncertain prospects. But Bigelow was more pragmatic than the idealistic Bryant. In 1858, he had defended Republican boss Thurlow Wood against what Bigelow the “Anti-Republican conspiracy” of Weed opponents. “It was John Bigelow who exposed this movement, with a slashing attack upon it and a bold defense of Weed,” wrote Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen. “The assault upon Weed, said the Post‘s associate editor, was an assault upon the very principles of freedom and Republicanism. It was being carried on by men who were ‘not worthy to unloose the latchets of Weed’s shoes.’ Weed had his faults and had made mistakes, but in Bigelow’s opinion he still towered far about his assailants. ‘We desire no better fate for the Republican party,’ declared Bigelow, than that it may never have a less disinterested leader and guide, than the editor of the Evening Journal.”4

Unlike Bryant, Bigelow supported William H. Seward for President. In March 1860, Bigelow warned Bryant that the alternative to Seward was Missouri Whig Edward Bates — which he thought would be a disaster for “the cause of freedom.” Bigelow wrote: “Now if you see any way to prevent such a catastrophe except the nomination of Seward, you see a great deal farther than I can. My own conviction is that Seward will be nominated. I do not see how ay other person can be; and if not nominated, I do not see how any other person who can be can be elected, for he has a very strong party of followers who would resent the nomination of a Clay Whig, the worst kind of Whig known, and one of a class with which for years Seward has had a relentless enmity.”5 Mr. Lincoln did not figure into Bigelow’s presidential calculations.

Over a year later, John Bigelow was appointed Consul General to Paris by President Lincoln to direct Union propaganda aimed at keeping France and England from aiding the South. The first indication of Bigelow’s appointment came in the form of a letter from Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward: “Mr. Motley goes out in the Europa, from Boston, August 21. Can you go at the same time?”6 Bigelow had been in Washington the previous month, nosing about for a possible appointment. He later wrote in Retrospections of an Active Life:

On the following day I left for Washington to learn from President Lincoln and Secretary Seward why they were sending me out of the country, as I had expressed to no one, nor experience, any desire for public employment. Mr. Seward said that the Government had selected me for the Paris consulate not primarily for the discharge of consular duties, which were then trifling and every day diminishing, but to look after the press in France. Our legations and consulates had been filled largely, not to say exclusively, during the Administration of President [James] Buchanan, with men of more or less doubtful loyalty, and London and Paris were swarming with Confederate emissaries. The officials and unofficials were all equally active in propagating the impression that the insurgent States had been wronged and oppressed by the Washington Government; that Confederates were fighting only for their common-law rights, not for slavery; that disunion was inevitable and imminent, and that neither the Washington Government nor the people of the Loyal States in the impending quarrel had any just claim to the sympathies or respect of any foreign power. Mr. Seward said it was important to dispel these impressions without delay. For this purpose he was anxious that the official representatives of the new Administration should hasten to their posts, and he relied upon me to see that the people of France were enlightened as speedily as possible in regard to the nature and extent of our domestic troubles.”7

The day after he received the telegram from Washington, Bigelow — accompanied by Secretary of State William H. Seward and New York Senator Preston King — met Mr. Lincoln for the first and last time in Bigelow’s life. President Lincoln “received us in his private room at an early hour of the morning; another gentleman was with him at the time, a member of the Senate, I believe. We were with him from a half to three-quarters of an hour. The conversation, in which I took little or no part turned upon the operations in the field. I observed no sign of weakness in anything the President said, neither did I hear anything that particularly impressed me, which, under the circumstances, was not surprising. What did impress me, however, was what I can only describe as a certain lack of sovereignty. He seemed to me, nor was it in the least strange that he did, like a man utterly unconscious of the space which the President of the United States occupied that day in the history of the human race, and of the vast power for the exercise of which he had become personally responsible. This impression was strengthened by Mr. Lincoln’s modest habit of disclaiming knowledge of affairs and familiarity with duties, and frequent avowals of ignorance, which, even where it exists, it is as well for a captain as far as possible to conceal from the public. The authority of an executive officer largely consists in what his constituents think it is. Up to that time Mr. Lincoln had had few opportunities of showing the nation the qualities which won all hearts and made him one of the most conspicuous and enduring historic characters of the century.”8

The fog which surrounded the appointment may have suggested the competition for the post. According to Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin in Lincoln and The Patronage, “The Paris consulate was eagerly sought after. John Bigelow, late part owner of the New York Evening Post, was a candidate for the place. For a time Seward and Thurlow Weed backed their journalistic ally, Henry J. Raymond, editor of the New York Times. Bigelow, in Washington, consulted with Weed, and the latter then informed him that ‘Seward…had intended it [the Paris consulship] for Raymond but the Times had behaved so it was impossible. Some one sent the Prest. [President] an article containing a savage attack on him. He read it, called Seward’s attention to it and made a remark which put it out of S’s power to mention Raymond’s name for anything to the Prest.’ Seward and Weed were partial to Bigelow, who, unlike the other partners of the Evening Post, Bryant and Parke Godwin, had supported Seward for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860 and had published a letter urging Seward for the Cabinet when the Chase men were trying to exclude him.”9

Bigelow’s position was particularly important because the new U.S. Minister William Dayton lacked the needed linguistic facility in French. Although President Lincoln appointed many Republican journalists to patronage positions at home and abroad, Bigelow was the most prominent New York journalist to be named to a diplomatic post and the most successful such appointment that Mr. Lincoln made. Ironically, the appointment was made by Secretary of State William H. Seward, a frequent editorial target of William Cullen Bryant. In his memoirs, Bigelow wrote that “with rather exceptional advantages for judging, I can think of no statesman then regarded as available for a Cabinet office in so many ways adapted for the conduct of our foreign affairs during the crises then impending as Mr. Seward.”10

Before the appointment Bigelow had already shifted his gears from journalism to other pursuits — selling his interest in the Evening Post in January 1861. “In the twelve years of John Bigelow’s connection with the Evening Post, beginning when he was a moneyless lawyer of thirty-one, he had become a man of considerably affluence. He owned a one-third interest in a property valued at $175,000 and had an annual income of about $25,000. With the paper increasing its advertising and circulation, he could look forward to becoming a wealthy man. But more important than the money had been his enjoyment of journalism. He never regretted taking the chance, when it was offered him of quitting the law to become a part owner of the Evening Post,” wrote Bryant biographer Charles H. Brown.11 Publicly, Bigelow indicated he intended to pursue writing projects. Privately, he hoped for an appointment though he was circumspect in seeking it. He had not been an enthusiastic supporter of candidate Lincoln, according to biographer Margaret Clapp:

In 1860 Bigelow could find no better reason for supporting him for the President [than party loyalty]….the ridiculous figure he cut, according to all accounts, his lack of background and the bawdy stories he told apparently without any awareness of the significance of the times or of his position, scarcely seemed to justify his election for the Presidency. However, Bigelow comforted himself, the candidate was probably unimportant; in the success of the party the stranglehold of slavery would be broken.12

Bigelow owed his appointment to Secretary of State William H. Seward and Seward’s political ally Thurlow Weed. and did not even meet Mr. Lincoln until after he learned of his appointment. After hearing from several sources — including an article in the New York Herald — that he was under consideration for Paris post, Bigelow went to Washington for several weeks in late June and early July 1861, but according to biographer Margaret Clapp, “he heard nothing more of the consulate. He met President Lincoln and was not impressed. He accepted [with] indifference the coolness of the Blairs and [Salmon P.] Chase, the result of his vigorous letter to the Post defending Seward’s conciliatory program and proclaiming the nation’s need of him as Secretary of State. He breakfasted and dined and drove with Seward. But no one except Weed mentioned a niche for him. Disgruntled, yet aware that a whole list of offices had to be settled, he went home…”13 During the 1860 campaign, Bigelow wrote an English friend:

Mr. Lincoln whom we have nominated for the Presidency is not precisely the sort of man who would be regarded as entirely a la mode at your splendid European courts, nor indeed is his general style and appearance beyond the reach of criticism in our Atlantic drawing rooms. He is essentially a Western man, he has passed most of his life beyond the Alleghenies, and owes few of the honors which his countrymen have conferred upon him, to the advantages of early education or of cultivated and refined associations. He is essentially a self made man and of a type to which Europe is as much a stranger as it is to the Mastodon. With great simplicity of manners and perhaps ignorance of the trans Atlantic world, he has a clear and eminently logical mind, a nice sense of truth and justice & a capacity of statement which extorted from Mr. Bryant the declaration that the address he delivered in this city last winter was the best political speech he ever heard in his life. I anticipate great advantages to the country from his election and by reflection I think that his administration will serve the cause of popular sovereignty throughout the world for I have no doubt that he will give it credit.14

Bigelow himself gave his government credit in his new post. Jay Monaghan wrote in Diplomat in Carpet Slippers: “A man with John Bigelow’s standing in the party might be expected to use his own discretion in carrying out orders from a chief whom he had bent to his own will. Soon people were saying that Bigelow’s appointment marked a change in the United States Government’s policy abroad. Diplomats never could be sure whether the guiding hand belonged to Lincoln, Seward or John Bigelow.”15

Bigelow had good connections in England and France. He “had traveled widely, read French fluently, and combined enterprise and insight with gracious manners. With [Edouard] Laboulaye in particular, he formed an alliance of great benefit to the North,” wrote Nevins.16 Laboulaye was a Sorbonne scholar who had read widely on American politics and culture — and later become one of the subjects of Bryant’s biographical works. Although Laboulaye was out of favor with Emperor Napoleon III, he was a valuable ally in the publicity wars which Bigelow waged in Paris. While still consul in 1863, Bigelow wrote Les Etats-Unis de’Amérique en 1863 to shift French public opinion toward the Union. After the Civil War, he chronicled France and the Confederate Navy.

Bigelow’s acquaintance with Britain and France was extensive. “He had been presented to Queen Victoria, knew the British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, and the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Lord John Russell. Bigelow was on friendly terms with such parliamentarians as [William F.] Gladstone, [Richard] Cobden and [John] Bright. Among English literary lights Bigelow was a welcome guest. He knew the latest gossip about Dickens’ love affairs and Mrs. Dickens’ jealousy. He had seen Thackeray in his cups, and was an old friend of war correspondent [William H.] Russell. Through the latter, Bigelow had met J. T. Delane, editor of the London Times. In addition to these qualifications, Bigelow was what might be called ‘a gentleman’ — very important to England in a war alleged to be between red republicanism and the older order of civilization.”17

Bigelow worked hard to move French newspapers toward more favorable attitudes regarding Union policies, but he had one blind policy spot. “Strenuously as Bigelow labored, however, he could not affect the course of the journals under government patronage and control,” wrote historian Nevins. “All of these semi-official sheets — the Constitutionel, Patrie, Pays — were advocating recognition throughout the spring of 1862. They harped upon the rigors of the blockade. To Bigelow, the blockade was a mistake. He did not believe it would do much if anything to end the war, feared that it might force cotton-hungry nations to intervene, and believed that as a matter of world policy, all blockades ought in the long run to be abolished. Had his wishes been met, one of the greatest weapons of the United States in gaining its victory over the Confederacy, and of the Allies in defeating Germany in 1918, would have been struck out of their hands.”18

Although Bigelow’s mentor, William Cullen Bryant, was a leader of the anti-Seward/anti-Weed faction of New York Republicans, Bigelow corresponded frequently with fellow journalist Thurlow Weed. At one point in early 1862, Bigelow wrote Weed, who was in London: “General [Winfield] Scott leaves for the United States to-morrow in the Arago. Every effort has been made to keep the departure a secret, and this will doubtless be the first notice you will have of it. The General was alarmed by the leading paragraph in the ‘Constitutionnel‘ this evening, purporting to give an account of a meeting held in Washington the 22nd [of December 1861] at which many members of Congress assisted. They are reported to have resolved that Mason and Slidell were lawful prizes, and that England has no claims for satisfaction. I told the General that that meeting signified nothing; that the whole tone of the American press gave no indication of a disposition to brave England in this matter; that no one defended the seizure in contemplation of its involving trouble with any foreign nation, and the fact that everybody argued the question at home was proof that there it was seen to have two sides, which was a tolerable security against any rash course of procedure. But the General was not in a humor to be convinced.”19 Later in the year, Bigelow was out of humor and pointedly inquired of Weed: “Why doesn’t Lincoln shoot somebody?”20

Although ensconced in Paris, Bigelow took an active interest in New York affairs. After the Republican Party’s 1862 defeat at the polls, he wrote that it was “the most fortunate event that has happened during the war, except the proclamation [of emancipation]….It will make the President and his advisers feel more than they have felt hitherto, the necessity of doing something (witness already McClellan’s decapitation) and it will give the Govt. a strong and watchful opposition for the want of which during the last two years the country has greatly suffered.”21 Bigelow wrote Senator Edwin D. Morgan after Morgan had been offered the position of Secretary of the Treasury in March 1865: “as your friend I am glad you declined it. The country is not yet ready to enter upon a systematic reform and reorganization of our financial policy. And until then woe is the man who, like Judas, carried the bag for Uncle Sam.”22

After the death of William Dayton in December 1864, Bigelow was appointed Minister to France, a job that he had already performed in all but name. However, certain complications had to be overcome. On December 21, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in his diary: “A numerous progeny has arisen at once to succeed him. John Bigelow, consul at Paris, has been appointed Chargé, and I doubt if any other person will be selected who is more fit. Raymond of the Times wants it, but Bigelow is infinitely his superior.”23

Former New York Senator Preston King wrote President Lincoln from Paris: “John Bigelow is our Counsul [sic] there — I know him well. He possesses the highest order of ability and all the best accomplishments of a gentleman[.] He has great learning as a Scholar and great common sense as a man[.] He knows and understands our Country at home. He has experience & knowledge of our affairs and relations in Europe and of public affairs and interests there — He possesses wisdom goodness and energy and I think him the best qualified man of our Country to fill the public place made vacant by the death of Mr Dayton[.] I earnestly recommend him to you and urge his appointment as minister to France.”24

The Minister’s job had been held out during the fall 1965campaign as a potential plum for New York Herald editor James Gordon Bennett, whose support President Lincoln desired in the 1864 election. Fortunately for France and the United States, Bennett rejected the job in March 1865. As Minister, Bigelow supervised the former secretaries of President Lincoln, John G. Nicolay and John Hay. Bigelow himself was replaced as consul by another New Yorker, General John A. Dix.

Upon his return to the New York, Bigelow spent most of his time writing books. However, he served as New York Secretary of State from 1876 to 1877 and became friendly with Democratic presidential aspirant Samuel J. Tilden. Had Tilden been inaugurated President in 1876, Bigelow probably would have named Bigelow as his Secretary of State. Instead, Bigelow became editor of the Tilden’s collected works. Bigelow’s special concentration, however, was the autobiography and writings of Benjamin Franklin, which he researched, edited and published. He also wrote a biography of his colleague, William Cullen Bryant, and his own memoirs, Retrospections of an Active Life. Bigelow’s interests extended to the building of the New York Public Library and the construction of the Panama Canal — both of which he actively promoted.

In his Retrospections, Bigelow wrote: “Lincoln’s greatness must be sought for in the constituents of his moral nature. He was so modest by nature that he was perfectly content to walk behind any man who wished to walk before him. I do not know what history has made a record of the attainment of any corresponding eminence by any other man who so habitually, so constitutionally, did to others as he would have them do to him. Without any pretensions to religious excellence, from the time he first was brought under the observation of the nation, he seemed like Milton, to have walked ‘as ever in his great Taskmasters’s eye.'”25

Bigelow concluded: “Looking back upon the Administration and upon all the blunders which, from a worldly point of view, Lincoln and his immediate advisers seemed to have made, and then pausing to consider the results of that Administration, so far exceeding in value and importance for the country anything which the most foresighted statesman had expected or conceived, we realize that we had what above all things we most needed, a President who walked by faith and not by sight; who did not rely upon his own compass, but followed a cloud by day and a fire by night, which he had learned to trust implicitly.”26

Footnotes

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 281 (New York Tribune).

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 281 (New York Evening Post).

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 341.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 236 (New York Evening Post, July 20, 1858).

- Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Volume I, p. 530 (Letter from John Bigelow to William Cullen Bryant, March 20, 1860).

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 364.

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 365.

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 366-367.

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 101-102.

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 290.

- Charles H. Brown, William Cullen Bryant, p. 426.

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 134.

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 146-147.

- Margaret Clapp, Forgotten First Citizen: John Bigelow, p. 136-137 (Letter from John Bigelow to William Hargreaves, July 30, 1860).

- Jay Monaghan, Diplomat in Carpet Slippers, p. 142-143.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 260.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, .

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 261-262.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 366 (Letter from John Bigelow to Thurlow Weed, February 1862).

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln, The War Years, Volume I, p. 590.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln, The War Years, Volume I, p. 609.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln, The War Years, Volume IV, p. 107.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 205 (December 21, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Preston King to Abraham Lincoln, December 21, 1864).

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 367.

- John Bigelow, Retrospections of an Active Life, Volume I, p. 368.