“The machinery for the Republican campaign of 1864 went into motion at noon on Washington’s birthday. [Republican National Chairman Edwin D.] Morgan called a meeting of the Union National Committee at his residence; the Committee sent out a call for a national convention to assemble at Baltimore June 7,” wrote Morgan biographer James A. Rawley.1 It was a convention at which were destined to play key roles: Morgan as the outgoing national chairman and convention convener; New York Times editor Henry J. Raymond as the chief author of the party platform and incoming party chairman; former Senator Preston King as chairman of the convention credentials committee; former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson as a possible candidate for Vice President; party boss Thurlow Weed as the chief defender of Secretary of State William H. Seward’s post in the Cabinet. In addition, noted historian Sidney David Brummer, George William Curtis “wrote the letter of notification to Lincoln” of his renomination.2

Although New York Republicans pulled together to back President Lincoln’s renomination in the spring of 1864, the differences continued and evidenced themselves in an attempt to promote a New York War Democrat as a candidate for Vice President — in order to knock Seward out of the Cabinet. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recorded in his diary on June 3 before the Baltimore Convention: “As the President is a Western man and will be renominated, the Convention will very likely feel inclined to go East and to renominate the Vice President also. Should New York be united on [John A.] Dix or [Daniel] Dickinson, the nomination would be conceded to the Empire State, but there can be no union in that State upon either of those men or any other.”3 Attorney General Edward Bates reported in his diary of July 17 after the Convention: “The Nat[iona]l. Intel[ligence]r. Of this morning contains a very sharp letter of Thurlow Weed, against the N.[ew] Y.[ork] Evening Post and the Radicals generally, and in favor of Mr. Seward[.]4

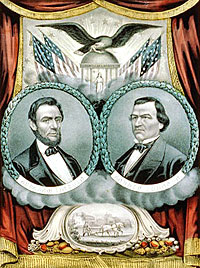

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The gathering met in the Front Street Theatre, festooned with flags and soon densely packed. At the outset, a rugged Kentucky parson, Dr. Robert J. Breckenridge of a ruling border-family, made a speech awesomely Radical in temper. Fortunately, few took him seriously when he said that the government must use all its powers to ‘exterminate’ the rebellion, and that the cement of free institutions was ‘the blood of traitors.’ Former Governor Morgan of New York called for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The platform, which received perhaps less note or discussion than usual, call upon the citizens to discard political differences and center their attention upon ‘quelling by force of arms the Rebellion now raging.’ No compromise must be made with Rebels and the demand was laid down for unconditional surrender of ‘their hostility and a return to their just allegiance…’ Slavery was the cause of the rebellion and thus there should be an amendment to the Constitution ending slavery. In addition to usual platitudes, harmony in national councils was called for Discrimination in the armies was to be ended, there was to be speedy construction of the Pacific Railroad; and of course, there was to be economy and responsibility by the Administration. Then came the ballot for President. Only Missouri voted for General Grant, and Lincoln received a renomination on the first ballot by a vote of 506 to 22. A Missourian moved that the nomination be made unanimous. Then, suffering fearfully from heat, humidity, and overcrowded hotels, the politicians concentrated their attention upon the one undetermined question — the Vice Presidency.”5

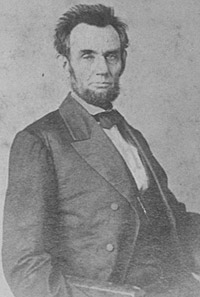

Morgan played a key role as a presidential agent. Before the convention, Morgan met with President Lincoln, who told him to advocate a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. Senator Morgan dutifully complied. He told the convention in his introductory speech: “It is not my duty nor my purpose to indicate any general course of action for this convention; but I trust I may be permitted to say that, in view of the dread realities of the past and of what is passing at this moment, and of the fact that the bones of our soldiers lie bleaching in every State of this Union, and with the knowledge of the further fact that this has all been caused by slavery, the party of which you, gentlemen, are the delegated and honored representatives, will fall far short of accomplishing its great mission, unless among its other resolves it shall declare for such an amendment of the Constitution as will positively prohibit African slavery in the United States.”6

According to Morgan biographer James A. Rawley wrote: “Morgan aimed to reconcile the two factions of the Union party. A few days before the Baltimore convention he was in correspondence with Horace Greeley, Radical spokesman. Greeley drafted four compromise resolves for incorporation in the platform. When the Tribune‘s editor learned that the conciliatory Morgan had sent the resolves to conservative Henry J. Raymond, editor of the Times and a mortal enemy, he blasted, ‘It is no use sending any thing I write to Raymond. He belongs to the party of eternal War, and his resolve on that point is as belligerent as possible.”7 Historian Sidney David Brummer noted: “The factional struggle in New York was…transferred to the Union National Convention.”8 Morgan, who was retiring as the Republican National Chairman after eight years in the post, spent little time at the convention. Raymond, who became new chairman of the Union National Committee, took on the chief role in crafting the platform.

Presidential aide John G. Nicolay reported back to the White House: “Things are going off in best possible style. There is not even a shadow of opposition to the President outside the Mo. Radical delegation, and I think even they if they get seats will go for him. Blow is understood to say that he will not take his seat in the Convention but will support Mr. Lincoln if nominated.” According to Nicolay, writing on June 6, “Hamlin will in all probability be nominated V.P. New York does not want the nominee — hence neither Dix nor Dickinson have any backers. Andy Johnson seems to have no strength whatever; even Dr Breckenridge and the Kentuckians oppose him. Cameron received no encouragement outside of Pennsylvania, and he is evidently too shrewd to bear an empty bush. The disposition of all the delegates was to take any war Democrat, provided he would add strength to the ticket. None of the names suggested seemed to meet this requirement, and the feeling therefore is to avoid any weakness. It strikes everybody that Hamlin fills this bill, and Pennsylvania has this afternoon broken ground on the subject by resolving, on Cameron’s own motion to cast her vote for him. New York will probably follow suit tonight, which will virtually decide the contest[.]” Despite the looming vice presidential conflict, Nicolay wrote: “The delegations being so unanimous for Lincoln are in a great measure indifferent about the other matters. All the day, everybody has been asking advice — nobody making suggestions. The Convention is almost too passive to be interesting — certainly it is not at all [as] exciting as it was at Chicago…”9

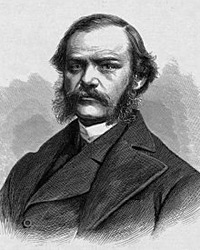

About few events in the Lincoln presidency are there so many contradictory stories as the replacement of Vice President Hannibal Hamlin of Maine with Tennessee Governor Andrew Johnson. The conflict as usual, involved New York. “At the national convention in Baltimore, there was less of a threat to Lincoln than to Seward,” wrote Seward biographer John M. Taylor. “A large segment of the party favored the replacement of Hannibal Hamlin as vice president — not because of any aversion to Hamlin but because of a general belief that the Union ticket could count on New England, and that Lincoln’s running mate should be someone with appeal outside traditional Republican states. Anti-Weed elements in the New York delegation were urging a conservative Democrat, Daniel Dickinson, for vice president. Weed recognized that the support for Dickinson was essentially a move against himself and Seward, because not even New York would be allowed to monopolize two positions as prestigious as those of vice president and secretary of state.”10

Although the Republican delegates had quickly unified behind President Lincoln’s renomination, they remained deeply split on the question of Vice President Hannibal Hamlin’s renomination. “The anti-Weed elements wanted Daniel S. Dickinson (Scripture Dick), a War Democrat whose honorable reputation and long record of public service gave him a formidable following beyond the boundaries of his native state. ‘Dickinson in, Seward out’ was the cry, the argument being that New York could not have both the Vice-President and the State Department,” wrote historian GlyndonVan Deusen.11 Historian Sidney David Brummer concluded that “the second place would probably have been conceded to the Empire State had the New York delegates reached an agreement. But they could not harmonize their differences. As a War Democrat and as a citizen of New York, Dickinson had desirable qualifications.”12 Historian James F. Glonek wrote:

On Monday morning, maneuvering for the vice-presidential nomination became more active. Senator [William P.] Fessenden, answering an urgent telegram from the Hamlin forces, came up from Washington to work among the New England delegations. Sumner tried to counteract his influence. After an informal caucus, several leaders of the Johnson movement decided to abandon him in favor of a New Yorker — Dix, Dickinson, Lyman Tremaine or Edwin D. Morgan. The Johnson movement faced defeat in their defection. If the entire New York delegation had united upon a single candidate, he would have received the support of many western delegations, and would probably have won the nomination.But the New York delegation, split between the War-Democratic faction backing Dickinson and the Weed-Seward element still favoring Hamlin, was unable to capitalize on this development. Instead, it divided still further as the Dickinson forces picked up supporters in the West, and the Seward faction, fearful that their leader would be forced out of the cabinet if New York received the vice-presidency, tried to launch a movement for General W.S. Hancock. Realizing that the New York stalemate was the pivotal point in the ultimate decision, many delegations withheld commitments until the Empire State delegates reached agreement.By Monday evening, as a result of the decline of the Johnson movement, the New York stalemate, and the activity of Morrill and Fessenden, Hamlin’s renomination seemed certain. Early that evening, Cameron personally declined the Pennsylvania delegation’s support in deference to Hamlin and the delegation unanimously concurred. Before ten o’clock, New Jersey, Kansas, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and the Radical delegation from Missouri also caucused in Hamlin’s favor. Massachusetts, the second most important source of Dickinson’s strength, appeared to be willing to swing to Hamlin’s support. In a ten o’clock New York caucus, Hamlin received 28 to 16 votes for Dickinson, 8 for Tremaine and 4 for Johnson. This balloting seemed to set the convention in Hamlin’s favor. Believing that Massachusetts and the rest of New England would come around, Morrill retired in full confidence of victory. 13

Historian Glonek added: “The Massachusetts ultimatum forced the Seward faction’s hand. In desperation, they dropped Hamlin and turned to Johnson. In a caucus held soon after the passage of the Massachusetts resolution. Johnson polled 32 votes to Dickinson’s 26 and Hamlin’s 8. When, after earnest discussion, a one-thirty caucus revealed the situation substantially unchanged, the delegation disbanded to prepare for an even more strenuous internal struggle the following day.”14

By keeping Dickinson off the vice presidential ballot, Weed succeeded in 1864 where he had failed in 1860 — in preserving the political future of William H. Seward. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Hannibal Hamlin, Joseph Holt, Ben Butler, Simon Cameron, John A. Dix, W.S. Hancock, Edwin D. Morgan, Andrew Curtin, and William S. Rosecrans all had advocates. Even the sixty-three-year-old War Democrat, Daniel S. Dickinson, who had done so much to rally New York after Sumter, was lustily supported by Middle State Radicals, and more slyly by Sumner and some New Englanders who saw that, if Dickinson were elected, Lincoln would have to drop Seward from the Cabinet. Sumner was in fact suspected of being a general marpot. he would rejoice if he could get Seward out of the Cabinet by the election of Andrew Johnson. At the same time, Seward, consistently filled with a desire to protect the rights of the freedmen, and in favor of a reorganization of parties that would attract the support of both Southerners and Northern Democrats, also showed a leaning toward Johnson. If the shelving of Hamlin resulted in his running against Fessenden for the Senate in Maine’s next Senatorial contest, Sumner would rejoin again, for he hated Fessenden. Seeing a plain threat to Seward, the latter’s friends vehemently opposed Dickinson. Hence, the situation became highly confused,” wrote historian Allan Nevins. 15

Thurlow “Weed would have been content to renominate Hamlin, and so thought a majority of the New York delegation, but the coolness of many New Englanders to the Vice-President and the outright opposition of Massachusetts made this impracticable.” wrote Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen.16 In particular, Charles Sumner, chairman of the Senate foreign relations committee and a rival with Seward for influence in foreign affairs, wanted the Secretary of State replaced. So Sumner rallied Massachusetts Republicans to replace Hamlin — not because he disliked Hamlin but in part because he preferred Hamlin to occupy the Maine Senate seat of William Pitt Fessenden, whom Sumner did dislike. Ironically, Fessenden did leave the Senate shortly thereafter — but to replace Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase at the beginning of July. The Baltimore event was more a grudge match than a convention.

Even before the convention, there were those who sought to replace Hamlin. According to historian William Frank Zornow: “Before the National Union Convention assembled at Baltimore on June 7, Lincoln showed his guiding hand once again in the selection of the Vice-Presidential candidate. In this matter he decided to make a concession to the radicals by offering the position to another of their favorites — Benjamin F. Butler. In 1892 Alexander McClure wrote that the President decided on Butler as his first choice as early as March 1864, and ‘reached the conclusion without specially consulting any of his friends. Simon Cameron, political boss of Pennsylvania, friend of Butler, and champion of Lincoln for re-election was chosen to be the emissary in this case. According to Butler’s account Cameron came to his headquarters and in the course of their conversation made the following offer:

‘The President, as you know, intends to be a candidate for re-election, and his friends indicate that Mr. Hamlin is no longer to be a candidate for Vice President, and as he is from New England, the President thinks that his place should be filled by some one from that section; and aside from reasons of personal friendship which would make it pleasant to have you with him, he believes that being the first prominent Democrat who volunteered for the war, your candidature would add strength to the ticket, especially with the war Democrats, and he hopes that you will allow your friends to co-operate with his to place you in that position.17

“When we arrived at the convention this interview with Mr. Seward made us a centre of absorbing interest and at once changed the current of opinion, which before that had been almost unanimously for Mr. Dickinson. It was finally left to the New York delegation,” recalled New York State Secretary of State Chauncey M. Depew. “The meeting of the delegates from New York was a stormy one and lasted until nearly morning. Mr. Dickinson had many warm friends, especially among those of previous democratic affiliation, and the State pride to have a vice-president was in his favor. Upon the final vote Andrew Johnson had one majority. The decision of New York was accepted by the convention and he was nominated for vice-president.”18 Historian James F. Glonek wrote:

“The critical situation within the Empire State delegation continued to wield a powerful influence on convention opinion. With the convention settled in favor of a War Democrat, and with no hope of New York’s reaching an agreement, numerous delegations held evening caucuses. Both Dickinson and Johnson profited from the extensive abandonment of Hamlin. Under the impetus of Weed’s promotion the waning Johnson movement was revitalized to surpass its original strength. Weed was confident that the Tennessean’s victory was inevitable. Late in the evening after turning the Seward faction’s leadership over to Raymond, the lobbyist left for New York,” wrote historian Glonek.“The political skirmishing continued after Weed’s departure. In a midnight caucus, Massachusetts, dissatisfied with the meager gains of the Dickinson movement, contemplated nominating General Butler. Although Connecticut and Iowa seemed receptive to his candidacy, the movement died in this midnight trial balloon. Meanwhile, the Seward faction sought further means to insure Johnson’s nomination. While Massachusetts was sponsoring the Butler movement, Raymond worked among a group of unrecognized delegations who were seeking admission to the convention. From Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the radical Blair element of Missouri, he secured a promise of support for Johnson if they were granted seats. With the assistance of Ohio and through the efforts of Preston King, chairman of the Committee on Credentials, all these delegations, with the exception of the Blair faction, were admitted to the convention.19

Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “There was also the New York delegation to consider for there was much support being given her native son Daniel S. Dickinson, who was the choice of the Unconditionals led by Lyman Tremain[e]. Before the convention Chauncey Depew and W. H. Robertson called on Seward who informed them Lincoln preferred the selection of Johnson. At the first meeting of the delegates, Hamlin and Dickinson had the greatest support. Weed was anxious to prevent the selection of Dickinson, for his election would have forced the resignation from the cabinet of William Seward, who was another New Yorker. Weed and Raymond had engineered the admission of the delegations from Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas in return for a promise to oppose Dickinson.

According to Zornow, “Raymond apparently was willing to see Hamlin renominated, but he swung over to Johnson when he learned that Massachusetts would not support Hamlin. Senator Sumner was trying to drive Seward from the cabinet by forcing the nomination of Dickinson and at the same time hoping to send Hamlin back to Maine to take the senatorial seat from Sumner’s old enemy William Fessenden. With Raymond’s help the Johnson movement gained headway in the New York delegation, and it was finally decided to give him thirty-two votes, Dickinson, twenty-eight, and Hamlin, six. (101).20 Historian Glonek wrote:

“The morning caucus of New York’s delegation revealed the basis of the imbroglio. Dickinson’s backers were carrying their state opposition to the Weed machine into national politics. They planned to win the vice-presidential nomination and thus force Seward out of the cabinet, since it was considered unfair for one state to have two representatives in the president’s official family. After the convention accepted the demand for a War Democratic nominee, the Seward faction, in order to protect the Secretary of State, were forced to drop Hamlin and support the nomination of a War Democrat capable of defeating Dickinson. In the three-hour morning caucus the Weed organization considered Judge Joseph Holt, General W. S. Hancock, and Andrew Johnson in turn. Preston King, a Seward supporter, pleaded with the delegation to favor a compromise Democrat from outside New York. George W. Curtis, a staunch Dickinson man, presented the real issue — if New York got the vice-presidential nomination it would prevent her from keeping her cabinet member, Seward. The caucus degenerated into a quarrelsome discussion of whether Seward or Dickinson should have a post in the national government. Both factions refused to forsake their cause. Thurlow Weed suggested Judge Holt as a compromise candidate, while Henry J. Raymond and Preston King favored Johnson. Since the Tennessee war governor possessed strength among various delegations, the Weed organization continued to back him. In spite of the fluctuation in Johnson’s support, he still offered the best chance for defeating Dickinson’s hopes. Late morning balloting in the delegation showed little change from the previous evening. The votes totaled 32 for Johnson, 28 for Dickinson, and 6 for Hamlin.21

Glonek added: “When the New Yorkers left their divided caucus for the convention floor, open antagonism among them continued. The Seward faction vehemently supported Johnson’s nomination. Weed, King, and Raymond continued to intimate that Lincoln trusted Johnson and warned that dissension would reign in their state if Dickinson was nominated. Dickinson’s backers, disgustedly viewing the later afternoon swing to Johnson, attempted to counteract the Seward influence by threatening to launch a movement in New York for General Grant for president. They threatened to wage an all-out battle in state politics if the Weed-Seward faction defeated their candidate’s aspirations.22

Weed biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “The New York leader then turned to Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, a War Democrat whose record compared favorably with that of Dickinson. Raymond agreed, as did a plurality of the new York delegation, and then Weed, Preston King and Raymond went to work on the convention. They emphasized Johnson’s humble origin, his war record, his pure character. The delegates were told of Lincoln’s trust in the tailor from Tennessee. It was pointed out that his nomination would eliminate the danger of political division in New York State. These arguments prevailed. Johnson was chosen on the first ballot. All was outwardly serene, and ‘Thad’ Stevens’s muttered comment about going down into ‘a damned rebel province’ for a candidate went unneeded.”23 Historian James F. Glonek wrote:

In the vice-presidential race ten candidates were in the field at the completion of the first ballot. At the balloting progressed it became evident that the contest was between Johnson, Hamlin, and Dickinson. None of the other seven candidates, Butler, [Joseph] Holt, General Lovell H. Rousseau, General Ambrose E. Burnside, Congressman Schuyler Colfax, ex-Governor David Tod of Ohio, or Preston King of New York had more than weak favorite son or complimentary vote support. On the roll call Johnson polled 200 votes to the vice-president’s 150, and 108 for the New York Democrat.During this roll call Cameron continued his calculated but futile efforts in behalf of Dickinson. The delegations of the Northeastern states, where the New Yorker’s support was strongest, had voted. While the remainder of the delegations were voting, Cameron, who had cast Pennsylvania’s 52 votes for Hamlin, conferred with the New York delegation. He promised to transfer Pennsylvania’s vote to Dickinson if the New Yorkers would united on him. Such action would have augmented Dickinson’s support by 90 Hamlin and Johnson votes. By bringing over other delegations which were under Weed-Raymond influence, it would have insured Dickinson’s nomination. Quite understandably, Seward’s New Yorkers refused Cameron’s offer.Johnson’s candidacy was saved. Immediately after the completion of the first ballot, Kentucky, Oregon, and the Kansas delegation, which had previously been split, cast their votes for Johnson. This gave the Tennessean a total of 231 votes, only 28 votes short of nomination. Then, over the protest of Thaddeus Stevens, Cameron threw Pennsylvania’s full vote to Johnson, thereby insuring his nomination. Subsequently it was made unanimous.This nomination by the Baltimore convention had not been produced by Abraham Lincoln. It was, instead, the product of curiously interrelated forces. Because of the general demand for a War Democrat, two strong candidates, Dickinson and Johnson, were able to organize extensive backing. Hamlin had substantial support but he failed because New England, his home section, failed to back him, and because Lincoln refused to act in his behalf. Although the president had been disappointed in Hamlin, who consistently supported Radical proposals during the war, he did not work to bring about the vice-president’s defeat. On the contrary, even when a deadlocked convention sought his advice, Lincoln remained consistently non-committal.”24

After Indiana nominated Andrew Johnson, according to contemporary journalist Noah Brooks, “Simon Cameron nominated Hamlin without any speech; Kentucky presented General [Lovell H.] Rousseau; and Lyman Tremaine, in behalf of a portion of the New York delegation, presented the name of Daniel S. Dickinson. The popular demand for a War Democrat had induced some of the New Yorkers to present Dickinson’s name, but it was well known that most of the New York delegates favored Hamlin, and their argument was that if Seward was to remain in the cabinet it could hardly be expected that a New York would be made Vice-President. There was much buttonholing and wirepulling while the vote was being taken, and before it was officially announced: but of the 520 votes cast Andrew Johnson had 202, Hannibal Hamlin 150, Daniel S. Dickinson 109, Benjamin F. Butler 289, and 31 votes were scattering; so there was not choice.”25 Thereafter, delegation after delegation fell in line behind Johnson.

Chauncey Depew recalled: “The candidacy of Daniel S. Dickinson, of New York had been so ably managed that he was far and away the favorite. He had been all his life, up to the breaking out of the Civil War, one of the most pronounced extreme and radical Democrats in the State of New York. Mr. Seward took Judge Robertson and me into his confidence. He was hostile to the nomination of Mr. Dickinson, and said that the situation demanded the nomination for vice-president of a representative from the border States, whose loyalty had been demonstrated during the war. He eulogized Andrew Johnson, of Tennessee, and gave a glowing description of the courage and patriotism with which Johnson, at the risk of his life, had advocated the cause of the Union and kept his State partially loyal. He said to us: ‘You can quote me to the delegates, and they will believe I express the opinion of the president. While the president wishes to take no part in the nomination for vice-president, yet he favors Mr. Johnson.'”26 Depew added:

When we arrived at the convention from New York was a stormy one and lasted until nearly morning. Mr. Dickinson had many warm friends, especially among those of previous democratic affiliation, and the State pride to have a vice-president was in his favor. Upon the final vote Andrew Johnson had one majority. The decision of New York was accepted by the convention and he was nominated for vice-president.27

Noted Seward biographer John M. Taylor: “The upshot was that Weed, working closely with Henry Raymond of the New York Times, rallied behind the vice-presidential candidacy of a border-state Unionist whose main qualification was that he was not from New York. The delegates at Baltimore concurred, and Andrew Johnson was chosen at Lincoln’s running mate. Lincoln himself appears to have played little part in the bargaining that resulted in Johnson’s nomination.”28

Footnotes

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 198.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 383.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 44-45 (June 3, 1864).

- Howard K. Beale, editor, The Diary of Edward Bates, p. 377 (June 17,1864).

- Allan Nevins, The War for Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 74-77.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 199.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 198.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 381.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 145 (Letter to John Hay, June 6, 1864).

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward, p. 231-32.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Thurlow Weed: Wizard of the Lobby, p. 307.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 381-382.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 263-265.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 263-265.

- Allan Nevins, The War for Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 75-76.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Horace Greeley: Nineteenth-Century Crusader, p. 308.

- Charles M. Hubbard, Thomas R. Turner and Steven K. Rogstad, The Many Faces of Lincoln: Selected Articles from the Lincoln Herald, p. 100 (William Zornow, “Lincoln’s Influence in the Election of 1864”).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 61.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 268-269.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 101-102.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 266-267.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 267-268.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, Horace Greeley: Nineteenth-Century Crusader, p. 308.

- James F. Glonek, “Lincoln, Johnson, and the Baltimore Ticket”, The Abraham Lincoln Quarterly, Vol. VI, No. 5, March 1951, p. 269-271.

- Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, p. 147.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 60-61.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 61.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward, p. 232.

Visit

Chauncey M. Depew

Daniel S. Dickinson

John A. Dix

John A. Dix (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Hannibal Hamlin (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Joseph Holt (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Andrew Johnson (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Alexander K. McClure (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Edwin D. Morgan

Edwin D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Henry J. Raymond

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Thurlow Weed

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Chauncey M. Depew

Daniel S. Dickinson

John A. Dix

John A. Dix (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Hannibal Hamlin (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Joseph Holt (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Andrew Johnson (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Alexander K. McClure (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Edwin D. Morgan

Edwin D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Henry J. Raymond

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Thurlow Weed

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)