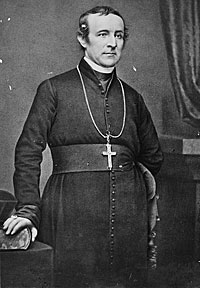

“It is an understatement to say that John Hughes was a complex character,” wrote Monsignor Thomas Shelley, who researched the life of New York’s first archbishop, John J. Hughes. “He was impetuous and authoritarian, a poor administrator and worse financial manager, indifferent to the non-Irish members of his flock, and prone to invent reality when it suited the purposes of his rhetoric. One of the Jesuit superiors at Fordham with whom he quarreled said, ‘He has an extraordinarily overbearing character; he has to dominate.'”1

“He was feared and love; misunderstood and idolized; misrepresented even to his ecclesiastical superiors in Rome, whose confidence in him, however, remained unshaken. Severe of manner, kindly of heart, he was not aggressive until assailed,” according to the Catholic Encyclopedia. “He was a forceful, impressive and convincing speaker; an able, resourceful and talented controversialist, a clear, logical and direct writer. His writing were usually hastily done, as occasion required, but commanded general attention from friend and opponent.”2

“Equally vigorous in disciplining lay trustees, in hitting back at nativists, and in setting up new churches, Hughes was particularly determined to reassert the traditional powers of the priesthood in church government,” wrote the authors of A History of New York State.3 Archbishop Hughes was a forceful speaker and domineering leader with special influence among Irish-Americans in New York City and special entree into the Lincoln Administration.

President Lincoln wrote that “having formed the Archbishop’s acquaintance in the earliest days of our country’s present troubles, his counsel and advice were gladly sought and continually received by the Government on those points which his position enabled him better than others to consider. At a conjuncture of deep interest to the country, the Archbishop, associated with others, went abroad, and did the nation a service there with all the loyalty, fidelity and practical wisdom which on so many other occasions illustrated his great ability for administration.”4

New York’s Catholic bishop had long fought anti-Catholic and nativist prejudice. Mr. Lincoln called on him to fight for the Union. Archbishop Hughes served as President Lincoln’s semiofficial envoy to the Vatican and to France in later 1861and early 1862. “The Archbishop was old, wise, and influential with foreign-born Catholics in America. A Whig in politics, he had been intimate with Weed and Seward for twenty years. Advancing age had not dulled the twinkle in his eye nor palsied the firmness of his step,” wrote Jay Monaghan in Diplomat in Carpet Slippers. “Before he embarked, Lincoln called him to Washington. Busybodies who saw the Archbishop enter Lincoln’s office speculated on the conference. The prelate came out with the mien of a man entrusted with a secret mission. He said that he was going to Europe — France, Spain, Italy — the Catholic countries. ‘Neither the North nor the South knew my mission,’ Hughes wrote a friend. ‘I alone knew it.”5

Seward was apparently more enthusiastic about sending Hughes on this mission than to include their mutual friend Thurlow Weed. Archbishop Hughes first declined to undertake the trip during a meeting with Seward in October 1861. But Archbishop Hughes insisted he would go only if he was accompanied by Weed. Secretary of State Seward was left with no choice. Weed recalled:

The secretary, after I came in, resumed the conversation and renewedly urged the Archbishop to accept. But he persisted in his declination, repeating, as I inferred, the reasons previously given for declining. The conversation was interrupted by a servant who ushered Baron von Gerolt, the Prussian minister, into the parlor. The Secretary seated himself with the baron upon a sofa in the ante-room, and I took advantage of the interruption to urge the Archbishop with great earnestness to withdraw his declination. He reiterated his reasons for declining. I told him that I had already listened attentively to all he had said, and that while I knew he always had good and sufficient reasons for whatever he did or declined to do, he had not yet chosen to state them; and that while I did not seek to know more than he thought proper to avow, I must again appeal to him as a loyal citizen, devoted to the Union, and capable of rendering great service at a crisis of imminent danger, not to persist in his refusal unless his reasons for doing so were insurmountable. After a long pause he placed his hand upon my shoulder, and, in his impressive manner and clear, distinct voice, said, “Will you go with me?” I replied, ‘I have once enjoyed the great happiness of a voyage to Europe in your company, and of a tour through Ireland, England, and France under your protection. It was a privilege and a pleasure which I shall never forget. I would cheerfully go with you now as your secretary or your valet, if that would give to the government the benefit of your services. And here the conversation rested until Baron von Gerolt took his leave. When Governor Seward returned the Archbishop rose and said, “Governor, I have changed my mind, and will accept the appointment with this condition, that he,” placing his hand again upon my shoulder, “goes with me as a colleague. And as you want us to sail next Wednesday, I shall leave for New York by the first tram in the morning. I lodge at the convent at Georgetown, and I will now take my leave. So good-night and good-by. I accompanied the Archbishop to his carriage where, after he was seated, he said with a significant gesture, ‘This programme is not be changed.”6

Archbishop Hughes wrote Weed shortly thereafter that “I do hereby appoint you, with or without the consent of the Senate, to be my friend (as you always have been) and my companion in our brief visit to Europe. The more I reflect upon the subject the more I am convinced that whether successful or not, the purpose is marked, in actual circumstances, by large, enlightened, and very wise statesmanship.” Weed met up with Hughes in New York City two days before their departure where Secretary of State Seward read to them their instructions. Among the reasons for the choice of Archbishop Hughes for the mission “were doubtless the contacts with notables which he had made on previous European visits, and the prestige he had gained through his financial and moral support of the papal cause whenever the temporal sovereignty of the Pope was imperiled. However, his anglophobe tendencies, which he tried vainly to overcome or disguise, would have unfitted him for effective service in England,” wrote Rena Mazyck Andrews.7 But even the U.S. Minister to Paris, William Dayton, seemed uncooperative to the Irish-American prelate. According to biographer Andrews, Dayton “was in no mood to encourage the diplomatic activities of an unofficial agent, and declined to arrange for the Archbishop’s presentation at court. Hughes then took matters in his own hands, with the result that a few days later he was being received with marked courtesy by [Emperor] Napoleon and [Empress] Eugenie at the Tuileries.”

In November the Union delegation met in Paris with Minister to France William Dayton, Minister to Belgium Henry S. Sanford, and John Bigelow, the influential journalist who was U.S. Consul in Paris. “Several hours were spent in discussing the situation and maturing a plan of action. Mr. Sanford and been connected with the American Embassy at Paris. Both he and Mr. Bigelow had familiar access to the clubs and to men in power. They pressed upon Mr. Weed the discouraging conviction that the French people would universally condemn the arrest of Mason and Slidell, of which tidings had just reached Paris,” wrote Thurlow Weed Barnes. “Various contingencies were considered at this consultation. “It was finally agreed that the Archbishop should immediately seek an audience with the Emperor. Mr. Weed, after inducing General [Winfield] Scott to outline a public letter, which Mr. Bigelow volunteered to write, was to cross the Channel, confer with Bishop McIlvaine, and see what could be accomplished in England. These arrangements perfected Mr. Weed retired with his colleague, Archbishop Hughes, to their apartments in the Hôtel de l’Europe. Subsequently the Archbishop’s audience resulted in a long courteous, but inconclusive conversation with the Emperor, from which it was impossible to extract the slightest crumb of comfort.”8 Biographer Rena Mazyck Andrews wrote:

To his imperial hosts he urged two courses of action. One was to mediate in the event of a war between the United States and England. The other was to make France independent of southern cotton by encouraging its culture in Algeria. But the Emperor declined to commit himself to either proposition….So gracious was his reception that the Archbishop went away highly elated and convinced that recognition of the Confederacy was not likely soon to occur. However, if we take into account the varied forces that were to influence the ultimate decision of Napoleon, it would seem that the imperial audience had been for Hughes a personal, rather then a diplomatic, triumph, Yet, not altogether without significance was the fact that after being relieved of his last apprehension of intervention by the pacific tone of the Emperor’s address at the opening of the Corps Legislatif, Hughes could depart for Rome feeling assured that he left behind a much friendlier feeling for America on the part of the French people than he had found on his arrival.In Rome the Archbishop basked in the favor of the Pope and his ministers. Meeting pilgrims and high ecclesiastics from every Catholic country, he continued to create sentiment for the Union cause. Repeating the tactics he had used with Eugenie, he convinced the Spanish bishops that their country’s hold upon Cuba would be endangered if the Confederates won the war.9

Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote that “the Archbishop became one of the President’s personal agents with full powers to set forth the Union cause in Europe. The Archbishop had interviewed the French Emperor, attended a canonization of martyrs in Rome, laid the cornerstone of a new Catholic university in Dublin built partly from moneys collected in America. In this tour of eight months over Europe the Archbishop spoke the pro-Northern views which he gave in a published letter to the pro-Southern Archbishop of New Orleans.”10 Hughes’ expenses of $5200 were paid by the government, but the archbishop actually proposed a more extensive tour of the continent that would have cost $10,000. The Lincoln Administration declined to underwrite such expenses.

Hughes had become a close ally of then New York Governor William H. Seward when in 1840 he started a campaign to get state funding for Roman Catholic schools to compete with schools run by the Public School Society which denigrated the Catholic religion. The issue forged an alliance between the usually pro-Democratic Catholic Church and the usually anti-immigrant Whig Party. Biographer Andrews wrote: “A serious detriment, however, to his influence at home was the wide-spread belief that he was a politician. The origin of this idea may be traced to his interest in national affairs and to his close relations with Thurlow Weed and William H. Seward. Somehow, behind the scenes, he was supposed to be politically active in their behalf, even as they, in turn reciprocated by promoting Catholic interests.”11

Like Seward and Weed, Hughes took an interest in patronage. One patronage applicant wrote President Lincoln in August 1862: “I have the honor to advise You that the most Revd Arch Bishop Hughes has kindly notified me that he will be in the City this evening, and that he will Seek an opportunity to Call upon You in referance [sic] to my application for the position of Collector for the 8th District of New York.”12 President Lincoln also sought Hughes’ advice on appointing hospital chaplains:

I am sure you will pardon me if, in my ignorance, I do not address with technical correctness — I find no law authorizing the appointment of Chaplains for the our hospitals; and yet the services of chaplains are more needed, perhaps, in the hospitals, than with the healthy troops soldiers in the field — With this view, I have given a sort of quasi appointment, (a copy of which I inclose) to each of three protestant ministers, who have accepted, and entered upon the duties-If you perceive no objection, I will thank you to give me the name or names of one or more suitable persons of the Catholic Church, to whom I may properly with propriety, tender the same service-Many thanks for your kind, and judicious letters to Gov. Seward, and which he regularly allows me both the pleasure and the profit of seeing. perusing.13

Hughes had influence in the Lincoln Administration, but his views were very different from those of Seward and President Lincoln on slavery. Biographer Rena Mazyck Andrews wrote in the 1850s that “despite the fact that the attitude of the Roman Church to slavery was one of studied silence, Archbishop Hughes could not resist publishing a controversial article entitled ‘The Abolition views of Brownson Overthrown.’ Here his protest against the hysterical propaganda of the abolitionists was so vigorous as to leave the impression in many minds that he was a zealous defender of the ‘peculiar institution’ as it then existed in the Southern States, if not an apologist for the slave trade.”14

When the South seceded, however, Hughes’ loyalty to the Union was clear and he expressed his views forcefully, especially in letters to Secretary of State Seward. According to Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg, “Cheers and applause greeted the public reading of a letter of John Hughes, Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Church of New York, declaring for the Star Stripes: ‘This has been my flag and shall be till the end.’ At home and abroad, the Archbishop would have it wave ‘for a thousand years and afterward as long as Heaven permits, without limit, of duration.'”

Hughes’ support for the War effort brought him a new source of criticism — American Catholics without loyalty and admiration of the South. They were sharply critical and some of their criticism reached the Vatican. President Lincoln apparently attempted to counter that criticism by writing that he “would feel particular gratification in any honor which the Pope might have it in his power to confer upon him.”15 Vatican authorities failed to respond to the President’s hint that Hughes be elevated to Cardinal. It was on Hughes’ successor that the honor of becoming the first American Cardinal was bestowed.

“Urging adequate protection of the national capital and a strict enforcement of the blockade, he urged even more the importance of opening the Mississippi,” noted biographer Rena Mazyck Andrews. “Among his own people he stimulated volunteer enlistments in the army and services of chaplains and nurses. One of his most inspiring appeals was addressed to the Catholic clergy of his province on ‘Duty to the Country.'”16 After his mission to Europe, Archbishop Hughes preached a sermon in which he urged that “volunteering continue and the draft be made; if 300,000 be not enough this week, next week make a draft of 300,000 more.”17

Although a supporter of the Union, Archbishop Hughes did not support President Lincoln on Emancipation and remained a supporter of the South’s right to maintain slavery. Historians Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace wrote: “Emancipation also alienated the Catholic Church hierarchy. Up till then Archbishop Hughes had been friendly with the administration, especially Secretary of State William H. Seward, his old ally on the education issue, and New York political boss Thurlow Weed.”18 Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg noted that President Lincoln “could not be oblivious to the viewpoint of which Seward as a friend of Archbishop John Hughes of New York was the spokesman, and Archbishop’s widely reprinted declaration in his official organ, the Metropolitan Record: ‘We, Catholics, and a vast majority of our brave troops in the field, have not the slightest idea of carrying on a war that costs so much blood and treasure just to gratify a clique of Abolitionists in the North.”19

Hughes’ was born in Ireland and ordained in Philadelphia. He became head of the New York diocese on the death of Bishop John Dubois in 1842 and archbishop of New York 1850 when New York was upgraded to an archdiocese. “When John Hughes came to New York in 1838, the diocese was 10 times the size of the present-day Archdiocese of New York,” wrote Monsignor Thomas J. Shelley. “It included all of New York state and the northern half of New Jersey, an area of 55,000 square miles, with about 200,000 Catholics. In that extensive diocese there were only 38 churches and 50 priests, two Catholic schools and a few orphan asylums. There was not a single Catholic College, seminary, rectory, hospital or other institution.”20

The next two and half decades were a time of tremendous growth for the city and the Catholic Church. According to Monsignor Shelley, “This rapidly growing Catholic population created an insatiable demand for more churches, schools and charitable institutions. In 1859 Archbishop Hughes boasted that he had dedicated 97 churches in the previous 20 years, an average of one new church every 10 weeks. In the area that remained part of the archdiocese, he established no fewer than 61 new parishes.”21 Archbishop Hughes was particularly active in attracting religious orders to set up charitable and educational organizations in New York. In August 1858, Archbishop Hughes laid the cornerstone for the current St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue — the most lasting monument to his ministry.

Archbishop Hughes was also a strong defender of Catholic rights against anti-immigration, Native American and Know-Nothing movements in the 1840s and 1850s. He packed Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in lower Manhattan in 1844 with his Catholic followers and prevented its destruction. Some of the enemies the Catholic prelate made were less easily intimidated. One fight in which Archbishop Hughes became engaged was with the owner of the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett. Bennett’s biographer, Don C. Seitz wrote: “As the Know-Nothing sentiment grew, the Archbishop became more virulent, thundering against Bennett in press and pulpit — rival editors being foolish enough to print his fulminations. He also, in effect, excommunicated the aggressive editor — all of which helped the Herald. Undauntedly the editor continued his crusade, and went so far as to demand the separation of the Catholic Church in America from the rule of Rome. He wanted an American church free from the overlordship of the hierarchy and argued at length.”22 Archbishop Hughes returned the enmity, calling Bennett “a very dangerous man.”23

When the draft riots hit New York City in July 1863, Governor Horatio Seymour asked a dying Archbishop Hughes to help restore order by speaking to his largely Irish flock from his Madison Avenue residence. Seymour wrote Hughes: “I do not wish to ask you anything inconsistent with your duties, but if you can with propriety aid the civil authorities at this crisis, I hope you will do so. Historian Frank Klement wrote: “Archbishop Hughes, in turn, wrote a letter and sent copies to the city’s newspapers, hoping that the letters would be published and his advice heeded. He asked all ‘Catholic rioters’ to ‘cease and desist’ from mob action and ‘unchristian practices,’ and return to peaceful pursuits and bring ‘the disorders’ to an end. Then he circulated (via a flyer) stating that he would give ‘a talk’ next morning (the sixteenth) from the steps of his residence.”24

However, it wasn’t until July 17, 1863, six days after the riots started, that Hughes gave the requested speech. The previous day he circulated a poster which said: “Men! I am not able, owing to the rheumatism in my limbs to visit you, but that is not a reason why you should not pay me a visit in your whole strength. Come, then, tomorrow, Friday at 2 o’clock to my residence, northwest corner of Madison Avenue and Thirty-sixth Street. There is abundant space for the meeting, around my house. I can address you from the corner balcony. If I should not be able to stand during its delivery, you will permit me to address you sitting; my voice is much stronger than my limbs. I take upon myself the responsibility of assuring you, that in paying me this visit or in retiring from it, you shall not be disturbed by any exhibition of municipal or military presence. You who are Catholics, or as many of you as are, having a right to visit your bishop without molestation.”25

Historian Iver Bernstein wrote: “On Friday, Archbishop John Hughes, who believed slavery should be tolerated, gave a speech outside his residence in which he urged that change be made through legal means.” Historian Frank Klement wrote that “a crowd estimated at 5,000 assembled in front of Archbishop Hughes’ residence. Suffering from rheumatism and a recent illness, and enfeebled with age, the revered churchman appeared, wearing the insignia of office. He addressed his flock as ‘my friends,’ saying that some had gone ‘astray.’ They were Catholics, he said, and so was he. They were Irish and so was he. The ‘disturbances’ must stop for the sake of their religion and for the sake of Ireland. ‘Violence begets violence.’ There was more. In closing, he asked ‘all’ to return peacefully to their homes and avoid mobs ‘where immortal souls are launched into eternity.’ After waving farewell, he limped back to his quarters. The crowd dispersed; its members returned peacefully and quietly to their houses and shacks.26 One Union officer, who worked to suppress the riot, later complained: “Such an effort, if made four days earlier, would have prevented incalculable suffering and loss.”27 Hughes delivered what historian William Alan Bales called “a good speech. But it came too late….The arrival of the military had made his talk academic” Hughes told the crowd:

Every man has a right to defend his home or his shanty at the risk of life. The cause, however, must be just. It must not be aggressive or offensive. Do you want my advice? Well, I have been hurt by the report that you were rioters. You cannot imagine that I could hear these things without being grievously pained. Is there not some way by which you can stop these proceedings and support the laws, none of which have been enacted against you as Irishmen and Catholics? You have suffered already. No government can save itself unless it protects its citizens. Military force will be let loose upon you. The innocent will be shot down and the guilty will be likely to escape.28

According to biographer Rena Mazyck Andrews, “While it may be that the insurrection had very nearly spent its force before Hughes made his appeal, and that military coercion and the promise of suspension of the daft were the most effective of arguments, yet the rambling speech of the fast-aging prelate was not without significance. Like his August sermon, the Archbishop’s message to the rioters was designed to reach a wider audience than his immediate hearers. It was a critical point in time and place, Hughes exerted his powerful influence to steady an allegiance that was wavering.”29

In The Great Riots of New York City, John Tyler Headley asked: “Why Archbishop Hughes took no more active part than he did in quelling this insurrection, when there was scarcely a man in it except members of his own flock, seems strange. It is true he had published an address to them, urging them to keep the peace; but it was prefaced by a long, undignified, and angry attack on Mr. Greeley, of the Tribune, and showed that he was in sympathy with the rioters, at least in their condemnation of the draft. The pretence that it would be unsafe for him to pass through the streets, is absurd; for on three different occasions common priests had mingled with the mob, not only with impunity, but with good effect. He could not therefore, have thought himself to be in any great danger. One thing, at any rate, is evident: had an Irish mob threatened to burn down a Roman Catholic church, or a Roman Catholic orphan asylum, or threatened any of the institutions or property of the Roman Church, he would have shown no such backwardness or fear. The mob would have been confronted with the most terrible anathemas of the church, and those lawless bands quailed before the maledictions of the representative of ‘God’s viceregent on earth.'”30

Historian Bales wrote that the Riots were “neither a Catholic insurrection nor a Catholic plot. The rioters being mostly Irish immigrants were, of course, Catholic. But they were not bent on Catholic errands, although they were themselves sometimes confused and so some of the violence was done in the name of protection against heretics. But most of the police were Irish, too, and Catholic, and no police have ever worked harder or stood more resolute in the face of danger or showed more courage or devotion to duty than the police during those first three terrible days.”31

Over the next five months, Hughes’ health continued to fail. His funeral in early January 1864 was a major public event in Civil War New York. Not everyone mourned. New York attorney and active Episcopalian lay leader, George Templeton Strong may have reflected elite WASP opinion: “Archbishop Hughes is dead. Pity he survived last June and committed the imbecility of his address to the rioters last July. That speech blotted and spoiled a record which the Vatican must have held respectable, and against which Protestants had nothing to say, except, of course, ‘Babylon,’ ‘Scarlet Woman,’ and ‘anti-christ.'”32

According to Carl Sandburg, the death of Archbishop Hughes took a political twist: Treasury Secretary Salmon P. “Chase took it on himself to see that the powers at Rome should, if possible, choose a proper prelate for the vacancy. And Chase wrote to the Most Reverend Archbishop Purcell of Cincinnati on February 1 letting that high official of the church know that he, Chase, was not idle: ‘Deeply impressed with the importance of having a successor to Archbishop Hughes, of clear intellect and earnest sympathy with the poor, the oppressed, and enslaved, I ventured, without consulting you, to ask Governor [William] Dennison, when here some time ago, to name the subject to the President. He did so, as he informed me at the time. Subsequently, I spoke to the President myself. He mentioned that Governor Dennison had spoken to him — seemed pleased with the suggestion — and referred me to Mr. Seward. Today I have had a conversation with Mr. Seward, who expresses himself in relation to the subject, as I would wish.”33

Footnotes

- Thomas J. Shelley, “Archbishop John Hughes and the Church in New York”, Catholic New York, (http://cny.org/archive/ft/ft070600.htm).

- Catholic Encyclopedia, (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07516a.htm).

- David M. Ellis, Jams A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 241.

- Mazyck Andrews, John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 15 (Letter from President Lincoln to the Very Rev. William Starr, Administrator of the Diocese of New York, January 13, 1864).

- Jay Monaghan, Diplomat in Carpet Slippers, p. 155-156.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, p. 635-636.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 6-7.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 350-351.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 7-8.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume II, p. 508.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 14.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John Foley to Abraham Lincoln, August 21, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to John Hughes [Draft], October 21, 1861).

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 4.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 10.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 5-6.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 10 (August 23, 1862).

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, p. 885.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume I, p. 568.

- Thomas J. Shelley, Archbishop John Hughes and the Church in New York, Catholic New York, (http://cny.org/archive/ft/ft070600.htm).

- Thomas J. Shelley, “Archbishop John Hughes and the Church in New York”, Catholic New York, (http://cny.org/archive/ft/ft070600.htm).

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 108.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume I, p. 355.

- Frank Klement, Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads of the North, p. 105.

- John Tyler Headley, The Great Riots of New York City, p. 254.

- Frank Klement, Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads of the North, p. 105.

- “Annals of the War Written by Leading Participants North and South”, Originally Published in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, p. 302 (T.P. McElrath, “The Draft Riots in New York”).

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 147.

- Rena Mazyck Andrews, Archbishop John Hughes and the Civil War, p. 4.

- John Tyler Headley, The Great Riots of New York City, p. 256-257.

- William Alan Bales, Tiger in the Streets: A City in a Time of Trouble, p. 147.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 390 (January 5, 1860).

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume II, p. 634.

Visit

James Gordon Bennett

John Bigelow

Winfield Scott (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William H. Seward

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Horatio Seymour

Thurlow Weed

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Thurlow Weed (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

New York Draft Riots