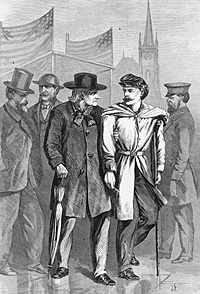

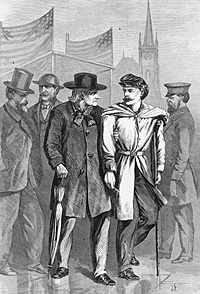

Bringing Invalid Soldiers to the Polls

Scene at the Polls in NY, the Veterans in 1812 and 1864.

Union Home and School for Soldier’s Children, 58th Street Near 8th Avenue

Soldier’s Depot, Dining Room (1st Floor)

Soldier’s Depot – Receiving Room (1st Floor)

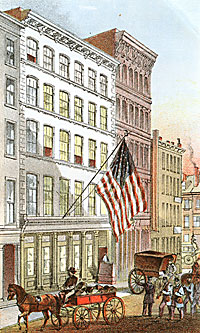

View of the NY State Soldier’s Depot, 50 & 52 Howard St.

Soldier’s Depot, Hospital (4th Floor)

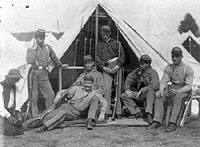

23rd New York Infantry

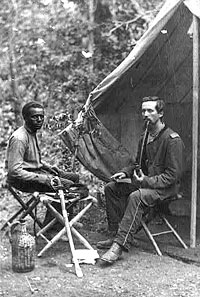

7th New York State Militia, Camp Cameron, D.C. 1861

Republicans perceived early that the soldier vote could be critical to victory in 1864. They proposed legislation in the spring of 1863 to allow Union soldiers to cast their votes through a proxy. New York Democrats understandably opposed this legislation. Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “The Democrats perceived that while they might safely fight this bill, it would be politically unwise to resist absolutely the giving of the ballot to the soldiers. Accordingly, when the Senate bill came up in the Assembly, Mr. Dean offered concurrent resolutions to amend the constitution so as to allow those in the federal military service to vote. Of course, such an amendment, requiring favorable action by two successive legislatures and ratification by the people would not permit the soldiers to vote until 1864.”1

The Democrats chose to delay but not destroy the proposal.

Even before the legislation came to a vote, Governor Horatio Seymour opposed the bill, telling the Legislature: “It is possible that the next Presidential election may be decided by the vote of a single State, and if votes by proxy are authorized, it is not impossible that such votes would, in such State, decide the election….It surely cannot be necessary to impress…the fearful danger which would attend the complication of the disastrous civil war…by the interposition of a well founded doubt as to the person rightfully entitled to the Presidential office.”2 However, after Attorney General Daniel S. Dickinson ruled that the legislation was constitutional, the bill passed the State Legislature. Governor Seymour vetoed it and the Assembly could not overrule his veto.

Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote: “Because Seymour had vetoed the bill giving the votes to soldiers absent in the field he entered the [1863] campaign under a cloud. The constitutional amendment on which he insisted did not authorize absentee voting until the election of 1864. As November approached, the Republicans besieged [Secretary of War Edwin M.] Stanton for furloughs which would permit soldiers to return to the state in order to cast their ballots there.”3 Mitchell quoted fellow historian Brummer who wrote: “The number of those who left Washington for middle an central New York was estimated at from sixteen thousand to eighteen thousand. The Democrats denounced this. TheTribune, in reply, defended it, saying that those furloughed were nearly all sick or wounded men, that the leaves of absence had been given without regard to party affiliations, and that the allegations that conditions of a political nature were attached to the furloughs were false.”4

Once the Republicans regained their hold on the Assembly in the 1863 elections, the scene was set for the Legislature to revisit the issue of soldier voting. According to historian Brummer: “The Unionists immediately took up the matter of the soldiers’ vote; for it was realized that dispatch was necessary if the volunteers were to vote at the ensuing presidential election. As the Democrats were committed to the constitutional amendment already passed by the previous legislature, and as any direct attempt on their part to block action on this subject would have merely created party capital for their opponents, there was no opposition to the second passage of the amendment; and thus it had gone through both houses without a dissenting vote before the session was a fortnight old. By the middle of February, a bill providing for a special election on March 8th, at which the amendment should be submitted to the people, was passed unanimously and signed.”5

Daniel H. Craig, president of the Associated Press, telegraphed President Lincoln on March 8, 1864: “New York City gives ninety five hundred (9500) majority for allowing soldiers to vote— Returns from interior show majorities same every where”6 Actually, the statewide margin was better than 5-1 for soldier voting. George Putnam recalled that President Lincoln subsequently wrote to General Ulysses S. Grant: “‘New York votes to give votes to soldiers. Tell the soldiers.’ The decision of New York in regard to the collection from the soldiers in each field of the votes for the coming Presidential election was in line with that arrived at by all of the States. The plan presented difficulties and, in connection with the work of the work of special commissioners, it involved also expense. It was, however, on every ground desirable that the men who were risking their lives in defence of the nation should be given the opportunity of taking part in the selection of the nation’s leader, who was also under the Constitution the commander-in-chief of the armies in the field. The votes of some four hundred thousand men constituted also an important factor in the election itself.”7

According to historian Brummer: “While some of the Democrats preferred the appointment of commissioners by the Governor and the Comptroller to visit the camps, fleets, and hospitals and collect the soldiers’ and sailors’ proxies, whereas the Unionists generally favored the plan of the bill vetoed by Seymour in 1863, the debates showed little partisan feeling. There was apparently on both sides a disposition to enact a measure which would leave no loopholes for frauds. In April, a bill providing that qualified voters in the service might transmit by mail their proxies to a friend or to the inspectors of election was passed, though with fifteen Democrats in the Assembly voting against it. There was some doubt whether Seymour would give his approval and whether he would not at least ask for changes. The Governor, however, finally signed the bill as passed, notwithstanding the fact that it was similar to the measure vetoed by him in 1863.”

Despite these maneuverings, the Democratic presidential game plan in 1864 also required the party’s candidate, General George B. McClellan, to do well among Union soldiers. McClellan’s closest advisors fully expected him to do so.8Unfortunately for this strategy, the Democrats adopted a peace platform at the same time that they were nominating McClellan at the end of August. The odd combination took the steam out of McClellan’s candidacy — especially from Democratic efforts to encourage soldier votes.

Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “Both parties appealed to the fighting men in their platforms, such a plank has become a standard fixture of most platforms since, but it was a new departure in 1864. A second significant development during the canvass of that year was the appearance of veterans’ organizations which were politically active. In September, a Democrat, fearing that the Unionists would not stop short of intimidation to force the soldiers to support Lincoln, urged McClellan to form a veterans’ society to offset this possibility. These clubs, he maintained, would generate enthusiasm, react upon the soldiers in the field, and contradict the assertion that all soldiers were for Lincoln. An organization known as the McClellan Legion grew out of this suggestion, and by October it was deeply involved in the campaign; to allay the possible accusation of treason, its officer made known that they did not accept Copperheads as members and repudiated the Chicago platform. The club, which soon had branches in the principal cities, held regular meetings and staged parades and rallies. The World reported that its influence was ‘tremendous.’ The Unionists were quick to realize the importance of capturing the veteran and soldier vote and retaliated by organizing the Veteran Union Club.9

Historian David E. Long wrote: “Among those who were reading these news stories were the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, and their reverence for their former commander began to diminish. The general feeling in the army was that his dismissal had been wrong and politically motivated, and that McClellan had good reason to be upset. However, his consorting with prominent Copperheads disappointed the troops he had nurtured and trained so devotedly. If he had any promise as a national political candidate, he had to retain the support of his army. The Army of the Potomac represented not merely the votes of 100,000 men, but also the votes of relatives and friends who relied on these men for news from the front. The soldiers were heroes to those they left behind and any action that hindered their effort was looked upon as disloyalty. Had McClellan been as astute a politician as he was a military organizer and theorist, he would have realized that the military vote represented his best chances of being elected and could have been more circumspect in his associations.” 10

Historian William C. Davis wrote: “McClellan’s supporters, and there were many, quickly found themselves on the defensive, thanks to the Chicago platform. When one man in the 144th New York declared, ‘Any man that supported the present administration and voted for Abe Lincoln this fall was a traitor to his country,’ his fellow privates spontaneously arrested him and confined him to the cook house.” 11

Such low-level politics had a high-level counterpart. “To get out the vote, the soldiers presented a special problem of the war-time election. Secretary of War Stanton took pains to stifle any flow of Democratic propaganda into the Army while opening the gates generously to equivalent Union Party materials. Even without this precaution, and despite the affection the Army of the Potomac felt for McClellan, the men in uniform were expected to favor Lincoln overwhelmingly. McClellan and the Democrats verged too close to threatening that the campaigns of the Army would become a waste,” wrote historian Russell F. Weigley. “Lincoln, in contrast, continued to offer substantive evidence of his concern for the Army and the soldiers, not only by vowing to see the war through to victory, but also by such a gesture as proceeding with a draft in September, the political risks notwithstanding, in order to keep the ranks of the Army filled. Thus Union Party workers saw the problem not as one of how the soldiers might vote but of whether they would be able to vote.” 12

New York State Republicans were fortunate that they had just elected in 1863 an energetic young Secretary of State, whose job included overseeing elections. In his memoirs, Secretary of State Chauncey M. Depew described New York’s outreach efforts: “In view of the approaching presidential election, the legislature passed a law, which was signed by the governor, providing machinery for the soldiers’ vote. New York had at that time between three and four hundred thousand soldiers in the field, who were scattered in companies, regiments, brigades, and divisions all over the South. This law made it the duty of the secretary of state to provide ballots, to see that they reached every unit of a company, to gather the votes and transmit them to the home of each soldier. The State government had no machinery by which this work could be done. I applied to the express companies, but all refused on the ground that they were not equipped. I then sent for old John Butterfield, who was the founder of the express business but had retired and was living on his farm near Utica. He was intensely patriotic and ashamed of the lack of enterprise shown by the express companies. He said to me: “If they cannot do this work they ought to retire.” He at once organized what was practically an express company, taking in all those in existence and adding many new features for the sole purpose of distributing the ballots and gathering the soldiers’ votes. It was a gigantic task and successfully executed by this patriotic old gentleman.”13

Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote that Depew was not cooperating with the Governor on soldier voting: “Seymour wrote the secretary twice but failed to receive an acknowledgement of either letter. Late in September he informed him: ‘I shall send a set of ballots to every regiment from New York. I will send them for both political parties, if you or any other person, will furnish me those for the candidates of the Republican party — or if you prefer to send them, I will give you any facility in my power. In a second letter dated October 1, the governor again called the management of the matter of the soldier vote to the attention of Depew, to whom the legislature had delegated the task of distributing Republican ballots:

Some days since I spoke with you, concerning the appointment by you and myself of joint Commissioners to proceed to the several United States Hospitals, and to visit the armies in the field, for the purpose of distributing ballots to our New York soldiers, now in the United States service, and to carry out the purposes of the law for soldiers voting.

As the day for the election approaches, every delay becomes injurious to our soldiers — and as I have heard nothing from you, with reference to a co-operation in making such appointments. I have selected several Commissioners to proceed to Washington and the Army of the Potomac to this end.

I shall be happy to add others if you will name them.

I have directed them to carry ballots for any parties that may see fit to put them into their hands.14

Apparently ignoring Governor Seymour, Secretary of State Depew enlisted other assistance. New York political boss Thurlow Weed wrote Secretary of State William H. Seward in mid September: “Our Secretary of State is alarmed about the Soldiers Vote. The Law is loosely drawn, and he says that they can, with Democratic Inspectors here, work in any number of Fraudulent Votes. This must be looked to, and yet it may be irremediable.”15 Secretary of War Stanton wasn’t completely cooperative in these efforts, according to Depew:

Of course, the first thing was to find out where the New York troops were, and for that purpose I went to Washington, remaining there for several months before the War Department would give me the information. The secretary of war was Edwin M. Stanton. It was perhaps fortunate that the secretary of war should not only possess extraordinary executive ability, but be also practically devoid of human weakness; that he should be a rigid disciplinarian and administer justice without mercy. It was thought at the time that these qualities were necessary to counteract, as far as possible, the tender heartedness of President Lincoln. If the boy condemned to be shot, or his mother or father, could reach the president in time, he was never executed. The military authorities thought that this was a mistaken charity and weakened discipline. I was at a dinner after the war with a number of generals who had been in command of armies. The question was asked one of the most famous of these generals: “How did you carry out the sentences of your courts martial and escape Lincoln’s pardons?” The grim old warrior answered: “I shot them first.”

I took my weary way every day to the War Department, but could get no results. The interviews were brief and disagreeable and the secretary of war very brusque. The time was getting short. I said to the secretary: “If the ballots are to be distributed in time I must have information at once.” He very angrily refused and said: “New York troops are in every army, all over the enemy’s territory. To state their location would be to give invaluable information to the enemy. How do I know if that information would be so safeguarded as not to get out?”

As I was walking down the long corridor, which was full of hurrying officers and soldiers returning from the field or departing for it, I met Elihu B. Washburne, who was a congressman from Illinois and an intimate friend of the president. He stopped me and said:

“Hello, Mr. Secretary, you seem very much troubled. Can I help you?” I told him my story.

“What are you going to do?” he asked. I answered: “To protect myself I must report to the people of New York that the provision for the soldiers’ voting cannot be carried out because the administration refuses to give information where the New York soldiers are located.”

“Why,” said Mr. Washburne, “that would beat Mr. Lincoln. You don’t know him. While he is a great statesman, he is also the keenest of politicians alive. If it could be done in no other way, the president would take a carpet bag and go around and collect those votes himself. You remain here until you hear from me. I will go at once and see the president.”

In about an hour a staff officer stepped up to me and asked: “Are you the secretary of state of New York?” I answered “Yes.” “The secretary of war wishes to see you at once,” he said. I found the secretary most cordial and charming.

“Mr. Secretary, what do you desire?” he asked. I stated the case as I had many times before, and he gave a peremptory order to one of his staff that I should receive the documents in time for me to leave Washington on the midnight train.

The magical transformation was the result of a personal visit of President Lincoln to the secretary of war. Mr. Lincoln carried the State of New York by a majority of only 6,749, and it was a soldiers’ vote that gave him the Empire State.

The compensations of my long delay in Washington trying to move the War Department were the opportunity it gave me to see Mr. Lincoln, to meet the members of the Cabinet, to become intimate with the New York delegation in Congress, and to hear the wonderful adventures and stories so numerous in Washington.16

Clearly, President Lincoln took an active interest in the soldier vote. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary in early October: “The President and Seward called on me this forenoon relative to New York voters in the Navy. Wanted one of our boats to be placed at the disposal of the New York commission to gather votes in the Mississippi Squadron. A Mr. Jones was referred to, who subsequently came to me with a line from the President, and wanted also to send to the blockading squadrons. Gave permission to go by the Circassian, and directed commanders to extend facilities to all voters,” wrote Navy Secretary Gideon Welles.17

It wasn’t just the votes that concerned Mr. Lincoln. There was a special bond between President Lincoln and soldiers. President Lincoln had a strong and almost mystical devotion to ordinary Americans, particularly soldiers. Writing to decline an invitation to speak at Cooper Institute on December 2, 1863, the President sent this message: “Honor to the Soldier, and Sailor everywhere, who bravely bear his country’s cause. Honor also to the citizen who cares for his brother in the field, and serves, as he best can, the same cause — honor to him, only less than to him, who braves, for the common good, the storms of heaven and the storms of battle.”18 Speaking ten months later to the 189th New York Volunteers, President Lincoln said:

SOLDIERS: I am exceedingly obliged to you for this mark of respect. It is said that we have the best Government the world ever knew, and I am glad to meet you, the supporters of that Government. To you who render the hardest work in its support should be given the greatest credit. Others who are connected with it, and who occupy higher positions, their duties can be dispensed with, but we cannot get along without your aid. While others differ with the Administration, and perhaps, honestly, the soldiers generally have sustained it; they have not only fought right, but, so far as could be judged from their actions, they have voted right, and I for one thank you for it. I know you are en route for the front, and therefore do not expect me to detain you long, and will therefore bid you good morning.”19

“No wonder,” wrote historian William C. Davis, “that, when a New York regiment marched up Broadway [in October 1864], and a spectator yelled out to ask whom they were going to vote for, nine of ten of them shouted back, ‘Old Abe.'”20 A letter in mid-September from President Lincoln to General William T. Sherman revealed the importance he — and Indiana Republicans — placed on soldier voting: “The State election of Indiana occurs on the 11th of October, and the loss of it, to the friends of the Government would go far toward losing the whole Union cause. The bad effect upon the November election, and especially the giving the State government to those who will oppose the war in every possible way, are too much to risk if it can be avoided. The draft proceeds, not withstanding its strong tendency to lose us the State. Indiana is the only important State voting in October whose soldiers cannot vote in the field. Anything you can safely do to let her soldiers, or any part of them, go home and vote at the State election will be greatly in point. They need not remain for the Presidential election, but may return to you at once. This is in no sense an order, but is merely intended to impress you with the importance to the Army itself of your doing all you safely can, yourself being the judge of what you can safely do.”21

These kinds of Republican efforts worried New York Democrats. David Black, biographer of Democratic National Chairman August Belmont, wrote: “As the election neared, August grew increasingly concerned about the possibility of voting fraud. The Lincoln administration appeared ready to use any method to win. August heard reports from Maryland that the Evening Post, the only Democratic newspaper published in Baltimore, had been closed by the commander of the Union troops in that area the day it printed the electoral ticket of the Democratic party. The chairman of the Democratic State Central Committee in Missouri told August that they were unable to campaign effectively because ‘soldiers will not allow a Democrat to open his mouth or even declare himself for McClellan, and the reign of terror prevails.'”22

Belmont wrote General McClellan in October: “General Grant is very favorably disposed & intends to see fair play & our rights protected.” Belmont detailed Henry Lansing to handle details of soldier voting.23 Historian Stephen W. Sears wrote: “McClellan devoted most of his campaign efforts to the army vote. Thirteen states had made some provision for their soldiers to vote, and it was expected that the general’s great popularity with the men in the ranks during his time in command would be reflected in the 1864 balloting. He sought out officers friendly to him to distribute Democratic campaign literature to the troops, and encouraged the formation of such military clubs as the McClellan Legion to rally ex-soldiers and men home on furlough and sick leave to his cause. Despite these efforts, however, no other segment of the electorate rejected his candidacy so strongly. In the final election count Lincoln would capture 55 percent of the vote; among the soldiers the president’s count was 78 percent. In spite of his acceptance letter, Northern soldiers perceived General McClellan as representing the party advocating peace at any price, and they turned against him by an overwhelming margin.”24

But Democrats weren’t averse to devising their own frauds, according to Lincoln biographer James G. Randall: “Some of the Democrats were even more eager than Lincoln and Seward to get the New York soldier vote, so eager indeed that they were willing to steal it. According to the New York proxy system, a soldier in the field sealed up his ballot and sent it to his home county to be opened for him on election day. A couple of zealous Democratic workers in Washington intercepted large numbers of these ballots, unsealed the envelopes, put in ballots marked for the Democratic ticket, and sent them on. These ‘ballot-box stuffers’ were said to have had more than twenty men at work for them and to have been ‘sending off the ballots, as fabricated by them, in dry-goods boxes full.'”25 Historian David Sidney Brummer wrote:

At the end of October occurred the revelations of alleged frauds in connection with the soldiers’ ballots. Both sides sent agents to the camps in order to procure these votes. One Ferry, New York State agent at Baltimore, as well as Edward Donohue and two others, Democratic voting agents, were arrested by the provost marshal at that city on the charge of impersonating officers and soldiers in the army of the United States, and as such forging on ballots and on the required accompanying affidavits the names of those in that service. At the same time, Colonel Samuel North, New York State agent at Washington, as well as Major Levi Cohen and Edward Jones, two subordinate officials at the state agency, were arrested on similar charges. The office was closed, and the soldiers’ ballots ready to be deposited were seized. Ferry pleaded guilty confessing to have signed the names of a number of soldiers and accusing Donohue of affixing the required officer’s name. Donohue at first denied complicity, and telegraphed for aid to Peter Cagger and to Sanford E. Church. Later Donohue confessed to having signed blanks with the name of “C.S. Arthur, captain and aid-de-camp,” but claimed that no offence was committed inasmuch as there was no officer by that name in the service of New York State or of the United States. In the press dispatches, it was alleged that several dry-goods boxes of forged votes for the Democratic national and state tickets had been forwarded to New York. Further, the Unionists were worked up over the discovery of a letter from Donohue to General Farrell of Governor Seymour’s staff, which read: “I send you…a number of ballots for your county. I have made out a number from the list you sent me…I guess you have enough. Fearing that you might not, I enclose envelopes and powers of attorney sworn to; you can fill them up for Columbia or any other county.”

Of course, the Unionists sought to make the utmost party capital out of this incident. The Tribune contained long editorials against the alleged frauds under such captions as ‘The Crime against the People,’ ‘Democratic Balloting among the Dead Soldiers,’ ‘Call the Roll Instantly;’ and it advocated the immediate organization throughout the State of ‘Vigilance committees, composed of men of nerve and familiar with their districts.’ [Brooklyn preacher Henry Ward] Beecher called the frauds monstrous. The Union State Committee issued an address, giving the “details of this gigantic attempt at fraud,”…

The Democratic press and stump speakers were indignant at the arrests. It was all a “Lincoln Plot.” They claimed that the witnesses were perjured and that the stories were manufactured to prevent McClellan ballots from being cast. Counter charges of fraud were made and it was declared that unfair obstacles had been placed in the way of Democratic agents. The Argus matched the Tribune editorials with one headed, “The Great Crime against the Soldiers.” It asserted that men in the army were voting by tens of thousands for McClellan and Seymour when the administration seized the ballots and arrested the agents; and the voters of New York were urged “to vindicate the rights of the soldiers and the cause of Republican government.” “In the story of outrage and crime which make up the black chronicle of a Lincoln Administration,” said another editorial, “there is no darker deed than this! It reveals the terror and desperation of the Washington junto.”

Governor Seymour issued a proclamation appointing three prominent Democrats, Amasa J. Parker, William F. Allen, and William Kelly, commissioners on behalf of the State of New York to proceed to Washington, inquire into the facts and circumstances of the arrests and “take such action…as will vindicate the laws of the State and the rights and liberties of its citizens, to the end that …all attempts to prevent soldiers from this State in the service of the United States from voting, or to defraud them, or to coerce their action in voting, or to detain or alter the votes already cast by them…may be exposed and punished.”

The commissioners, on arriving at Washington, protested against the jurisdiction assumed by the United States in the case. They obtained the seized ballots, but they failed to secure the release of North, Cohen, and Jones, or even the postponement of their trial until after the election. The commissioners’ report, published in the press two days before the election, declared that while there might have been irregularities, they had found no evidence that any frauds had been committed by any person connected with the New York agency. The document also contained a harrowing account of the treatment of the prisoners, which must have fed Democratic indignation against the arbitrary actions of the administration.26

Historian Stewart Mitchell’s review of this incident is more favorable to Seymour’s commissioners: “These commissioners saw Secretary Stanton and visited Colonel North, who was under lock and key together with an assistant named Cohn, in the Old Capitol Prison, which then stood on the site of the new Supreme Court Building. After talking with North the commissioners demanded the release of the two prisoners, but Judge [Joseph] Holt countered with a flat refusal. Then they appealed to Lincoln, who was cordial but would give them no satisfaction: the arrested agents must await their trial. Parker and his associates returned to Albany. Long after the election — on January 6, 1865 — North, Cohn, and a third agent, by the name of Jones were brought up for trial before a military commission. All three prisoners were acquitted and turned loose. An apologist for this proceeding acknowledges that the state law was both ‘complicated and foolish’ and ‘full of opportunities for mistake and fraud.’ The same author asserts that Colonel North was a man of high character and may fairly be believed to have been innocent of any wrong-doing whatever. He had merely spent a little more than two months in one of Stanton’s jails.”27

Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “Newspapers on both sides maintained that the soldiers would support their candidates. Union papers filled columns with letters from soldiers to relatives and friends emphasizing the army’s hatred for Democrats, while the Democrats replied with myriads of letters denouncing Lincoln. The Union party performed its work of propaganda so effectively that on election eve the army seemed to have been completely Lincolnized.”28

It wasn’t just patriotism and propaganda that affected soldier votes. Historian Philip S. Paludan wrote: “Soldiers may have been influential in the voting in a more subtle way. Commanders with Lincoln’s permission sent troops to places where trouble was expected because of the dubious loyalty of the neighborhoods. New York City draft riots gave the army an excuse to police the polls in that city and to provide, according to General [Benjamin] Butler, the first honest election in decades.”29 Historian William C. Davis wrote: “Lincoln and Stanton had feared that there would be attempts to disrupt the voting in New York, and actually had [Ulysses] Grant ship a few regiments north to the city to provide security. In fact there was no outbreak, and the soldiers, being New York regiments, had to be kept on their barges all day on the New Jersey side of the Hudson so that they were not technically in their home state; otherwise the ballots they had cast in the field would have been nullified.”30

Historian James McPherson wrote: “In none of the states with separately tabulated soldier ballots did this vote change the outcome of the presidential contest — Lincoln would have carried all of them except Kentucky in any case. But in two close states where soldier votes were lumped with the rest, New York and Connecticut, these votes may have provided the margin of Lincoln’s victory.”31 According to historian William C. Davis, “Certainly soldiers’ votes may have decided some vital and otherwise close state contests, especially New York, Indiana, and Illinois, for the kinds of Lincoln majorities in the regiments that soldiers from those states recorded in their diaries revealed that they were voting overwhelmingly for Lincoln. Nevertheless, the loss even of such powerful states could not have dented Lincoln’s sure electoral victory, but only reduced his majority and his mandate.”32 Historian William Frank Zornow wrote:

“In determining the outcome of the presidential election, the soldier vote was not a decisive factor. Of the total vote cast in the field, Lincoln received 119,754 to McClellan’s 34,291. In such states where soldiers had to return home to vote, definite results are more difficult to obtain. In Connecticut, where Lincoln won by a scant 2,406 votes, the fighting men cast 2,898 for him, thus assuring him victory in that state. Governor Cannon of Delaware insisted that it was the failure to get troops to vote which cost the Union party a victory in his state. The close results of the October elections convinced Lincoln and his managers that they might not carry Pennsylvania. McClure estimated that he might win by a scant 6,000, but suggested that to play safe 30,000 troops should be sent home from Grant’s and Sheridan’s armies. Lincoln was hesitant to make such a request from the hard-pressed Grant, but at length troops were obtained from [George] Meade and [Philip H.] Sheridan. They could have been better employed at the front, for Lincoln carried the state by 5,712 home votes, but the boys in blue contributed an additional 14,363 to make the victory more conclusive. New York had adopted a law permitting voting in the field. Depew went to the capital to see Stanton to learn the whereabouts of certain regiments from his state so that ballots could be distributed. The Secretary would not impart this information. When he heard of this, Washburne exclaimed: ‘Why that would beat Mr. Lincoln. You don’t know him. While he is a great statesman, he is also the keenest of politicians alive. If it could be done in no other way, the president would take a carpet bag and go around and collect those votes himself.’ Lincoln paid a personal visit to Stanton after being informed of the incident, and Depew returned to New York with his precious information. ‘It was the soldiers’ vote,’ said Depew that gave him the Empire State.’

Only in Connecticut and New York did the soldiers’ vote affect the outcome of the election, but even then Lincoln would have carried the popular and electoral vote of the North. Several congressmen owed their seats to the army voters, but even had they not been chosen, the Union party would still have controlled the Thirty-ninth Congress.”33

By a 3-1 margin, soldiers who voted in the field rejected their former commander and supported their commander-in-chief. Historian William C. Davis wrote: “Soldiers left no doubt that they saw in the outcome something greater than just an election result, and they shared this vision with Lincoln, who had helped them to see it. A New York sergeant called it ‘a grand moral victory gained over the combined forces of slavery, disunion, treason, tyranny.'”34Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote that the closeness of the vote led the Albany Argus to charge repeatedly “that soldiers’ ballots for the Democratic candidates were being systematically detained, and that the State had been carried for the administration by fraud.”35

Of course, one group of soldiers wasn’t encouraged to participate in this democratic exercise. Historian John Hope Franklin wrote: “In New York [in 1861] they formed a military club and drilled regularly until the police stopped them.”36 Despite the opposition of Governor Horatio Seymour, interest in raising a black regiment revived in 1863. According to historian Allan Nevins, “In the end the angry citizens persuaded the War Department to take the units they organized into the army under national, not State, authority. The Twentieth New York, departing for the front, was given an ovation which in heartfelt enthusiasm equaled that tendered the Seventh New York in the first days of war. Two more colored regiments followed. But Seymour had hopelessly delayed the effort of the Empire State, which should have outstripped that of Massachusetts.”37

Footnotes

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 279.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 281.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 347.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 351-352.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 360.

- George Haven Putnam, Abraham Lincoln; the People’s Leader in the Struggle for National Existence, p. 153.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 369.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 199.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, p. 57.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men: How President Lincoln Became Father to an Army and a Nation, p. 208.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Daniel H. Craig to Abraham Lincoln1, March 8, 1864).

- Russell F. Weigley, A Great Civil War, p. 380.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 52-53.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 377-378.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Thurlow Weed to William H. Seward, September 18 [1864]).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 53-55.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 175 (October 7, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 32 (Letter to George Opdyke, Joseph Sutherland, Benjamin F. Manierre, Prosper M. Wetmore and Spencer Kirby).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 75 (October 24, 1864).

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men: How President Lincoln Became Father to an Army and a Nation, p. 215.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 11 (Letter to General William T. Sherman. September 19, 1864).

- David Black, The King of Fifth Avenue, p. 255.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 614 (Letter from August Belmont to George B. McClellan, October 11, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 588-589.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 256.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 432-433.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 380.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 200-201.

- Philip S. Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 289.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men: How President Lincoln Became Father to an Army and a Nation, p. 218.

- James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 804-805.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men: How President Lincoln Became Father to an Army and a Nation, p. 224.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 201-202.

- William C. Davis, Lincoln’s Men: How President Lincoln Became Father to an Army and a Nation, p. 225.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 439.

- John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans, p. 272.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, p. 525.