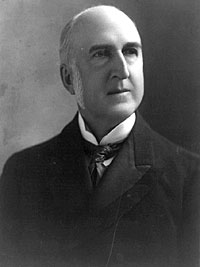

Had Chauncey M. Depew “devoted himself to politics exclusively there is no office in the United States he might not legitimately aspire to,” wrote Lincoln chronicler Allen Thorndike Rice. “He is one of the foremost orators in the country, and as an after-dinner speaker is unrivaled. He charms a cultivated audience by his subtle humor, and a general audience by his flowing wit; is, in fact, so flexible that he can readily and easily adapt himself to circumstances.”1

The young Yale graduate and lawyer was first elected to the New York Assembly in 1861. In the 1863 legislative session, Chauncey Depew was a likely candidate for speaker of the State Assembly, but the body was evenly split between Republicans and Democrats. A Democratic assemblyman offered Depew a deal in which the Assemblyman, T.C. Callicot of Brooklyn, would get the speakership in exchange for assuring that outgoing Governor Edwin D. Morgan was elected Senator by a joint session of the two houses. Two other Democrats offered a counter proposal by which Depew would be elected speaker. Depew chose the Callicot alternative because “the government at Washington needed an experienced senator of its own party, like Edwin D Morgan, who had been one of the ablest and most efficient of war governors, both in furnishing troops and helping the credit of the country. I finally decided to surrender the speakership for myself to gain the senatorship for my party. I had difficulty in persuading my associates, but they finally agreed. Callicot was elected speaker and Edwin D. Morgan United States senator.”2

It was a highly contentious contest in which Democrats repeatedly tried to block a vote — coming near to violence at some points. According to historian Sidney David Brummer, Callicot was accused of having entered into a corrupt agreement with the Chairman of the Republican-Union State Committee and another member of that body, by which Callicot was to vote with that party in effecting an organization of the House and in the election of a United States senator in return for his own election as speaker and for an amount of money sufficient to enable him to pay certain private debts….”3

Depew’s good nature and oratorical prowess stood him in good stead in the Civil War. He had risen rapidly in politics after graduation from Yale. Depew served one and a half terms in the State Assembly before he seeking statewide office in 1863. Depew cut a deal whereby a Democrat was elected Speaker of the Assembly in February 1863 — and a Republican, Edwin D. Morgan, was elected to the Senate. By himself, he collected political IOUs for the future. Depew’s friend Wayne MacVeagh convinced him to campaign for the Republican ticket in Pennsylvania, where the vote was held in early October, before campaigning for his own election as New York Secretary of State in November. “When I returned to New York to enter my own canvass, the State and national committees imposed upon me a heavy burden. Speakers of State reputation were few, while the people were clamoring for meetings,” wrote Depew. “The programme laid out called upon me to speak on an average between six and seven hours a day. The speeches were from ten to thirty minutes at different railway stations, and wound up with at least two meetings at some important towns in the evening, and each meeting demanded about an hour. These meetings were so arranged that they covered the whole State. It took about four weeks, but the result of the campaign, due to the efforts of the orators and other favorable conditions, ended in the reversal of the Democratic victory of the year before, a Republican majority of thirty thousand and control of the legislature.4

As Secretary of State Depew was in a position to make political connections and help other Republicans. He was in a position to do a favor for Utica Republican Roscoe Conkling, who wanted to seek his old congressional seat in 1864 but was afraid of Republicans allied with the Seward-Weed machine:

When I was elected secretary of state I received a note from Mr. Conkling, asking if I would meet him. I answered: “Yes, immediately, and at Albany.” He came there with Ward Hunt, afterwards one of the associate justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. He delivered an intense attack upon machine methods and machine politics, and said they would end in the elimination of all independent thought, in the crushing of all ambition in promising young men, and ultimate infinite damage to the State and nation. “You,” he said, “are a very young man for your present position, but you will soon be marked for destruction.”

Then he stated what he wanted, saying: “I was defeated by the machine in the last election. They can defeat me now only by using one man of great talent and popularity in my district. I want you to make that man your deputy secretary of state. It is the best office in your gift, and he will be entirely satisfied.”

I answered him: “I have already received from the chiefs of the State organization designations for every place in my office, and especially for that one, but the appointment is yours and you may announce it at once.”

Mr. Conkling arose as if addressing an audience, and as he stood there in the little parlor of Congress Hall in Albany he was certainly a majestic figure. He said: “Sir, a thing that is quickly done is doubly done.” Hereafter, as long as you and I both live, there never will be a deposit in any bank, personally, politically, or financially to my credit which will not be subject to your draft.”5

Depew learned early how to reconcile political differences. He recalled in his memoirs: “Mr. Lincoln told me of an experience he had in his early practice when he was defending a man who had been accused of a vicious assault upon a neighbor. There were no witnesses, and under the laws of evidence at that time the accused could not testify. So the complainant had it all his own way. The only opportunity Mr. Lincoln had to help his client was to break down the accuser on a cross examination. Mr. Lincoln said he saw that the accuser was a boastful and bumptious man, and so asked him: ‘How much ground was there over which you and my client fought?’ The witness answered proudly: ‘Six acres, Mr. Lincoln.”Well,’ said Lincoln, ‘don’t you think this was a mighty small crop of fight to raise on such a large farm?’ Mr. Lincoln said the judge laughed and so did the district attorney and the jury, and his client was acquitted.”6

“I saw Mr. Lincoln a number of times during the canvass for his second election,” Depew later wrote. “The characteristic which struck me most was his superabundance of common sense. His power of managing men, of deciding and avoiding difficult questions, surpassed that of any man I ever met. A keen insight of human nature had been cultivated by the trials and struggles of his early life. He knew the people and how to reach them better than any man of his time. I heard him tell a great many stories, many of which would not do exactly for the drawing-room; but for the person he wished to reach, and the object he desired to accomplish with the individual, the story did more than any argument could have done.”7

Depew noted: “Every one wanted something and wanted it very bad. The patient president, wearied as he was with cares of state, with the situation on several hostile fronts, with the exigencies in Congress and jealousies in his Cabinet, patiently and sympathetically listened to these tales of want and woe. My position was unique. I was the only one in Washington who personally did not want anything, my mission being purely in the public interest.”8

Depew, who was allied with the Seward-Weed-Morgan wing of the party, played an important role in heading off at an attempt to undermine Secretary of State William H. Seward at the 1864 Republican Convention in Baltimore. According to historian William Zornow, “In order to assure the nomination of [Andrew] Johnson the support of New York was also needed. The Empire State had its own favorite son, Daniel S. Dickinson, who was being supported for the Vice-Presidency. William H. Seward, apparently aware of the President’s desires, took Chauncey Depew and Judge Robertson of the New York delegation aside at the convention and told them, ‘You can quote me to the delegates, and they will believe I express the opinion of the President. While the President wishes to take no part in the nomination for Vice-President yet he favors Mr. Johnson. Depew and Robertson carried this message to the delegates who acted accordingly and supported Johnson. The nomination of Johnson was a triumph of Lincoln’s political skill, for Hannibal Hamlin was very popular with the delegates.”9

After leaving the office of Secretary of State, Depew resumed his law practice and began legal work for the New York & Harlem Railroad — eventually rising to president and chairman of the board of the New York Central Hudson River Railroad Company. His attempts to win political office were unsuccessful — including one attempt to become the Republican candidate for president — until he was elected to the Senate in 1899. He represented New York State there until 1911 and subsequently returned to law and business.

Footnotes

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 637.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 25.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 270.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 33.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 82.

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 326-327.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 427 (Chauncey M. Depew).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 55-56.

- William Zornow, The Many Faces of Lincoln, p. 101-102.