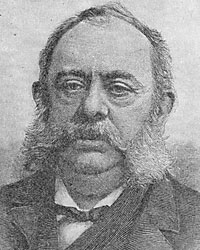

Samuel Latham Mitchell Barlow, wrote historian Stephen W. Sears “was a rising young corporation lawyer in Wall Street” when he met George B. McClellan in 1854. Both men were then twenty-eight. “Active in Democratic politics as well as in business circles, he specialized in railroad affairs. He was a cultivated bon vivant, with a taste for fine paintings and first editions, and he and McClellan became lifelong friends.”1 Barlow helped McClellan get his first job on leaving the Army in 1856 — as an executive of the Illinois Central Railroad. “They had first met two years earlier, when McClellan was investigating railroad construction methods for [then Secretary of War] Jefferson Davis. Barlow’s motives in this case were not entirely altruistic, for through McClellan he hoped to forge a link between the Illinois Central and the Ohio and Mississippi, a road in which he held a substantial interest,” wrote Sears.2

Barlow had a keen instinct where money was concerned and became one of the wealthiest lawyers in the country. McClellan had a keen instinct for power and when he saw civil war on the horizon in 1858, he asked for Barlow’s help in getting back into the army: “The plain truth of the matter is, that the war horse can’t stand quietly by, when he hears the sound of the trumpet.”3

“Barlow is a lover of luxury,” wrote Paul R. Cleveland in the year before Barlow died. “His home is the double-brown-stone house, at Madison and Forty-third street, and is filled with pictures, engravings, bric-a-bac, bronzes, books and other fine things which men of culture and taste and wealth enjoy.” Cleveland wrote that Barlow was “often spoken of as an Englishman, perhaps because he has many English friends and affects various English ways. He has a good mind, much diligence, great energy, and, early in his practice, was engaged in several very important railway cases, to which he has mainly confined himself.”4 Barlow’s New York Times‘ obituary stated: “The act of which he gained his widest fame was the lawsuit which expelled Jay Gould from the control of the Erie Railway after the death of James Fisk Jr. The English and other ill-used stockholders of the railroad had long been looking for an opportunity to oust the manipulator into whose hands the property had fallen.”5

The Times noted “Mr. Barlow was a Democrat in politics, and was so during and before the war, when he was an apologist for slavery.”6 General McClellan’s friendship with Barlow helped define him politically — as a conservative Democrat. But Barlow’s friendship with McClellan targeted him for scrutiny by the War Department. Historian Sears wrote: “In March [1863] T. J. Barnett had written Samuel Barlow from Washington to warn him that Stanton’s detectives considered Barlow and other Democratic leaders ‘fit subjects for summary acts.’ Barnett urged him to be cautious, and added, ‘A noble chivalric fellow near you — beg him to be prudent.'”7

McClellan often unburdened himself of his problems, protestations, and prejudices to Barlow. In early November 1861 shortly after McClellan had been named general-in-chief, he wrote: “I feel however that the issue of this struggle is to be decided by the next great battle, & that I owe it to my country & myself not to advance until I have reasonable chances in my favor. The strength of the Army of the Potomac has been vastly overrated in the public opinion. It is now strong enough & well disciplined enough to hold Washington against any attack — I care not in what numbers. But, leaving the necessary garrisons here, at Baltimore etc — I cannot yet move in force equal to that which the enemy probably has in my front.”8

That same month, Barlow had played an unusual role in bringing McClellan together with Democratic attorney Edwin M. Stanton when McClellan sought advice about the legal implications of the “Trent Affair.” He introduced McClellan to Stanton the “same evening…which was the beginning of their acquaintance.”9 The correspondence between the two suggested that they were trying to position McClellan politically. Barlow wrote Stanton on November 21: “I am glad to learn by the papers of to-day that there has been a collision of sentiment between [Secretary of War Simon] Cameron and [Secretary of the Interior Caleb B.] Smith. Such quarrels should be fostered in every proper way, though the General [McClellan] must, if possible, keep entirely free of. Since my return home I have met hundreds of our most prominent citizens, and my ability to speak with confidence as to the power of our army, and especially my entire belief in McClellan, have enabled me, I think, to be of real service. I have been of course very careful not in any way to undertake to represent McClellan’s views in any respect, while the fact that I saw so much of McClellan most effectually closes my mouth on the subject of his movements, though in fact I really know nothing.”10 It apparently was public knowledge that fellow Cabinet members Cameron and Smith had gotten into a heated argument about the use of black soldiers.

Stanton biographer Frank Abial Flower wrote: “The foregoing Barlow letter discloses that the politicians of the party to which McClellan belonged were already engaged in an effort to hamper and break down the administration by promoting quarrels among its members, the beneficiary of which was to be free from them.”11 Stanton was more careful. He replied two days later: “I think the General’s true course is to mind his own Department and win a victory. After that all other things will be of easy settlement.”12 Less than two months later in January 1862, Stanton was to replace Cameron as Secretary of War and become one of McClellan’s fiercest critics. The Cabinet appointment effectively torpedoed the plans of Stanton and Barlow to become law partners in New York City and eventually torpedoed their friendship.13 Barlow tried, however, to stay loyal to Stanton, whom he called “a firm, consistent Union man, but as firm a Democrat as I know….I know he is all right & he is withal a man of strong mind & will have his own way.”14

Barlow had managed to ingratiate himself even more thoroughly with McClellan by January. The general, who had been bedridden for several weeks, wrote: “I owe you replies to about a dozen notes & thanks for at least the same number of acts of kindness, not forgetting these boots! Let me thank you in a lump & assure you that my thanks are none the less sincere for being crowded together in this style. I am quite well now but still weak — the trouble is that they don’t give me time to recover — but allow me not one minute of rest when I need it most.”15

Although McClellan’s supporters were quick to envisage his political candidacy, McClellan himself was more reticent. New York Customs Collector Hiram Barney told the Lincoln Cabinet in early 1862 about “a conversation he had with Barlow some months since. Barlow… had been to Washington to attend one of McClellan’s grand reviews when he lay here inactive on the Potomac. McClellan had specially invited Barlow to be present, and during this visit opened his mind, said he did not wish the Presidency, would rather have his place at the head of the army, etc., etc., intimating he had no political views of aspirations.”

Barlow contributed to McClellan’s problems with Stanton by arranging for transmission by the Associated Press of an article which manufactured fulsome praise of McClellan by Stanton at a meeting of railroad managers in late February 1862. Stanton told New York Tribune Managing Editor Charles A. Dana: “The paragraph to which you call my attention is a ridiculous and impudent effort to puff the General by a false publication of words I never uttered. Sam Barlow of New York, one of the secretaries of the meeting, was its author, as I have been informed.”16

McClellan’s venom for Stanton shown through in a June 1862 letter to Barlow: “I have only time to thank you for your kind letter of the 17th, as well for the great kindness Mrs B & you have shown to my wife. By a recent arrival from Washington I hear that Chase & Stanton have parted company, & that [General Irvin] McDowell has attached himself to Stanton! They have got themselves into a nice scrape with their White House business — I have written to Frank Blair requesting him to call for my letter to the Secty on the topic. Never was there a more groundless slander & never a malicious lie more thoroughly exposed than this than this will be when all is known about it. The worst of it is that Stanton knew the facts before the subject was agitated in Congress & did not choose to explain — my letter has incorporated in it what had passed between S & myself & will expose his treachery most completely!”17

Barlow turned his own venom on his erstwhile friend Stanton. After President Lincoln visited former General Winfield Scott in West Point in June, 1862, “Barlow, a bitter enemy of the Secretary since falling afoul of Stanton’s security apparatus, spread the word that he was insane,” wrote Stanton biographers Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman.18 “The New York World was the mainspring of the attack on Stanton. Its able publisher, Manton Marble, was a partisan Democrat, heartily Unionist, and wholly dedicated to increasing the circulation of his newspaper. An anti-Stanton stand, he and his associate Barlow had decided, was good for the country and for the World. His correspondents on the Peninsula, favored by McClellan and angry at Stanton’s press restrictions, sent Marble the kind of dispatches he wanted.”19

But Barlow tried to patch up McClellan’s quarrel with Stanton, according to McClellan biographer William Starr Myer. In August letter to McClellan, Barlow warned about McClellan’s enemies in Washington. “I know your aversion to the schemes, the tricks and even the policy of politicians,” wrote Barlow to McClellan. “If a compact is made I understand it to be simply this. That you and your friends, so far as you can control them, shall say nothing of the past, except to the extent necessary to defend yourself. Mr. Lincoln has assumed all the responsibility. You will meet Mr. Stanton as a friend and he shall in return give you his confidence and his support.”20

In mid-July 1862, General McClellan wrote Barlow: “I have lost all regard and respect for the majority of the Administration, & doubt the propriety of my brave men’s blood being spilled to further the designs of such a set of heartless villains. I do not believe that Stanton will go out of office — he will not willingly, & the Presdt has not the nerve to turn him out — at least so I think. Stanton has written me a most abject letter — declaring that he has ever been my best friend etc etc!! Well, burn this up when you have read it. Give my kindest regards to the Madame & believe me truly your friend.”21 Meanwhile, McClellan wrote his wife that Stanton was “the most unmitigated scoundrel I ever knew, heard or read of…”22

“Your two kind letters received, the last this evening,” wrote McClellan to Barlow a week later. “I will briefly reply to both at once. I have not been in any manner consulted as to [Henry W.] Halleck’s appointment & it is intended as ‘a slap in the face.’ I do not think it best to reply to the lies of such a fellow as [Senator Zachariah] Chandler — he is beneath my notice, & if the people are so foolish as to believe aught he says I am content to lose their favor & to wait for history to do me justice. I am in my own mind satisfied that I will be relieved from the command of this Army, & shall then leave the service. I am weary, very weary, of submitting to the whims of such ‘things’ as those now over me — I have suffered as much for my country as most men have endured, & shall be inexpressibly happy to be free once more.”23

In early September, Customs Collector Hiram Barney showed up at the White House when a discussion of McClellan was underway. After endorsing the confidence that soldiers felt in McClellan, “Barney proceeded to disclose a conversation he had with Barlow some months since. Barlow…had been to Washington to attend one of McClellan’s grand reviews when he lay here inactive on the Potomac. McClellan has specially invited Barlow to be present, and during this visit opened his mind, said he did not wish the Presidency, would rather have his place at the head of the army, etc., etc., intimating he had no political views or aspirations. All with him was military, and he had no particular desire to close this war immediately, but would pursue a line of policy of his own, regardless of the Administration, its wishes and objects,” reported Navy Secretary Gideon Welles.24

Another relationship that helped define Barlow politically was that with financier August Belmont. In 1861, Barlow put Belmont together with a young journalist who was to become a key part of the Democratic political machine in New York, Manton Marble. “To be successful the Democrats would need a reliable newspaper. Samuel Barlow found one that was looking for investors: the New York World, a fairly new newspaper run by Manton Marble, a twenty-seven-year-old poet and free-lance writer,” wrote Belmont biographer David Black.25 Although Belmont was reluctant to spend still more of his money on political ventures, he yielded to Barlow’s entries and in 1862 they took over a controlling interest in Manton’s World.

Another of Barlow’s acquaintances was Postmaster General Montgomery Blair who in 1863 and 1864 cultivated him as a potential conduit to General McClellan. McClellan biographer Stephen W. Sears wrote: “Pointing to his unbroken record of support for the general, Montgomery Blair opened a correspondence with Samuel Barlow designed to gain a number of goals — to see Mr. Lincoln re-elected and General McClellan restored to army command, while in the process frustrating the objectives of radical Republicans.”26 Blair wrote William H. Seward in late October 1863: “The subject of the enclosed letter from Sam Barlow is of sufficient importance to render it proper to submit it to you & it may be that may have information otherwise which will make its statements valuable.’27 Seward turned the letters over to President Lincoln to read. Barlow wrote that Southerners might be willing to abolish slavery in order to maintain the Confederacy and get European diplomatic recognition. In early May 1864, Blair wrote Barlow that McClellan should avoid the immediate temptations of politics and wait for a more opportune moment: “I believe if he would unbosom himself unreservedly & in confidence directly with the President that he would give him a military place in which he could be most useful….”28 McClellan replied to Barlow: “I will not sacrifice my friends my country & my reputation for a command. I can make no communication to Mr. Lincoln on the subject.”29

Barlow was not, however, changing political allegiances with such correspondence. He served, according to McClellan biographer Stephen W. Sears “without title, as George McClellan’s political manager in 1864 and took the part of chief strategist during his presidential campaign, yet he refused to attend the Democratic nominating convention. After Manton Marble arrived there and tested the delegates’ mood, he telegraphed McClellan, ‘Barlow must come out to Chicago…with full decision as to platform & with authority general & full.’ McClellan did not intervene, however, for Barlow explained that his presence in Chicago would in fact be ‘positively harmful.’ He argued that the McClellan managers at the convention were so jealous of one another’s influence with the general that he, the closest confidant of all, would be rendered ineffectual by their envy.”30

After the convention Barlow helped McClellan draft his acceptance of the Democratic presidential nomination — which tried to balance the Democratic Platform’s “peace plank” with an appeal to Union soldiers. The last draft of the letter included two final sentences written in Barlow’s handwriting: “I realize the weight of the responsibility to be borne should the people ratify your choice. Conscious of my own weakness, I can only seek fervently the guidance of the Ruler of the Universe, and, relying on His all-powerful aid, do my best to restore Union and Peace to a suffering people, and to establish and guard their liberties and rights.”31

Later in September, Barlow wrote McClellan: “Lincoln pretends to have a letter of yours to himself, written in 1861, I believe, in which you advised him to assume dictatorial powers, arrest members of Congress &c &c. This story is likely to hurt us very much in certain quarters. Have you a copy of any such letter and if, not can you give me the substance.”32 McClellan replied: “I have carefully thought over the matter & cannot think of anything I ever wrote or said that could be tortured into giving Lincoln the advice in question. You may be sure that it is a lie out of the whole cloth.”33

Barlow persistently tried to involve McClellan in his own campaign and McClellan persistently sought to avoid such involvement. He considered politics beneath his dignity. But reluctant Barlow slaved on. He wrote McClellan in late October: “You can have no idea of the work we are doing. I have hardly ate or slept for ten days, while my house has become a miniature Tammany Hall.”34 Although Barlow wrote that McClellan had an “even chance of success,” the results turned out to be far from even. Although President Lincoln’s margin in New York to 7000 votes, the Democratic presidential ticket won only Delaware, Kentucky and New Jersey.

After the Democratic defeat in the 1864 election, Barlow wrote McClellan: “For your want of success I am sorry. I believed that in your election lay the only hope of peace with Union. Under Mr. Lincoln, I see little prospect of anything, but fruitless war, disgraceful peace, & ruinous bankruptcy. But I cannot resist the feeling…that if you had been triumphantly chosen, you would be today more to be pitied, than envied.”35 McClellan replied: “For my country’s sake I deplore the result — but the people have decided with their eyes wide open and I feel that a great weight is removed from my mind. I have sent in my resignation and have abandoned public life forever — I can imagine no combination of circumstances that can ever induce me to enter it again — I say this in no spirit of pique or mortification — it is simply the result of cool judgment. I shall hereafter devote myself to my family and friends, & leave to others the grateful task of serving an intelligent, enlightened and appreciate people!”36 McClellan wrote Barlow: “I fully appreciate the work that my friends have done, & their motives — no man, I think, ever had more or truer or nobler friends than I — would that I could thank them all, as I do you, for the devotion with which they have fought this bitter & desperate fight — if we have been unsuccessful we have at least, thank God, no cause to be ashamed.”37

Stanton biographer Frank Abial Flower wrote: “If McClellan had followed the advice given by Stanton in the Barlow letter of November, 1861, which was to ‘mind his own Department and win a victory’ — ‘keep out of politics’ — he might have been elected president in 1864 — certainly in 1868.”38

Footnotes

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 51.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 51.

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 112 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, January 3, 1858).

- Paul R. Cleveland, “The Millionaires of New York, Part II”, Cosmopolitan Magazine, October 1888, .

- “Samuel L. M. Barlow”, New York Times, July 11, 1889, .

- “Samuel L. M. Barlow”, New York Times, July 11, 1889, .

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 51.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 127-128 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L. M. Barlow, November 8, 1861).

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 121.

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 123 (Letter from Samuel L.M. Barlow to Edwin M. Stanton, November 21, 1861).

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 122.

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 122 (Letter from Edwin M. Stanton to Samuel L.M. Barlow, November 23, 1861).

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 116-117.

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 141.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 154 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, January 18, 1862).

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 130.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 306 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, June 23, 1862).

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 204.

- Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, p. 212.

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 394.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 361 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, July 15, 1862).

- William Starr Myers, General George Brinton McClellan, p. 395.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 369 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, July 23, 1862).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 117 (September 8, 1862).

- David M. Black, The King of Fifth Avenue, p. 219.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 364.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Montgomery Blair to William H. Seward, October 24, 1863).

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 364.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 364-365.

- Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, p. 371.

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 596-597 (Letter from George B. McClellan to September 8, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 603 (Letter from Samuel L.M. Barlow to George B. McClellan, September 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 602 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, September 23, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 614 (Letter from Samuel L. M. Barlow to George B. McClellan, October 27,1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 619 (Letter from Samuel L.M. Barlow to George B. McClellan, November 9, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 618 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L.M. Barlow, November 10, 1864).

- Stephen W. Sears, editor, The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865, p. 618-619 (Letter from George B. McClellan to Samuel L. M. Barlow, November 10, 1864).

- Frank Abial Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 197.