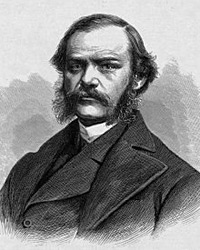

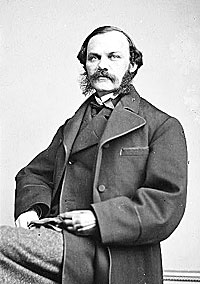

Henry Jarvis Raymond

Residence of Henry Raymond, 12 West Ninth Street

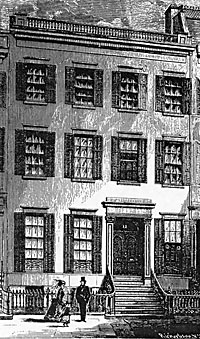

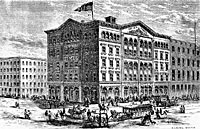

N.Y. Times Building

Letting the cat out of the bag!!

The Impending Crisis

New York Times

“By far the most interesting member of the legislature was the speaker, Henry J. Raymond,” wrote Chauncey M. Depew, who was a freshmen member of the State Legislature in 1862. The Governor of New York at the time, Edwin D. Morgan described Raymond as “the Speaker of the Assembly as is quite apparent to all who read the debates of that body.”1 Raymond served as speaker during the 1862 session — as he in the early 1850s. Raymond was not, however, the undisputed leader of the body — having to contend with others whom he had defeated to be elected Speaker. And even his prodigious powers of public speaking did not ensure that his views prevailed on issues like taxation and harbor defenses.

Depew later recalled: “He was one of the most remarkable men I ever met. During the session I became intimate with him, and the better I knew him the more I became impressed with his genius, the variety of his attainments, the perfection of his equipment, and his ready command of all his powers and resources. Raymond was then editor of the New York Times and contributed a leader article every day. He was the best debater we had and the most convincing. I have seen him often, when some other member was in the chair of the committee of the whole, and we were discussing a critical question, take his seat on the floor and commence writing an editorial. As the debate progressed, he would rise and participate. When he had made his point, which he always did with directness and lucidity, he would resume writing his editorial, an example which seems to refute the statement of metaphysicians that two parts of the mind cannot work at the same time.”2

“Mr Raymond’s tact was one of his most notable qualities,” wrote contemporary biographer Augustus Maverick. “Better than the majority of men, he possessed the power of keeping his temper under control. He was never betrayed by anger into discourtesy. In this hours of business, in the office of the Times, the sole indication of a disturbance of his mental equilibrium was his occasional rapid transit through the outer editorial room to his private office, with an emphatic clink of his boot-heel upon the floor, but utter silence of the tongue. Curiosity was at once awakened, and, within the hour, some derelict person, who had made a blunder, or disregarded an order, was seen emerging, discomfited, from the presence to which he had been summoned, — for Raymond was always a strict disciplinarian, and in this fact, coupled with his own intimate knowledge of the proper quality of newspaper work, lay part of the secret of his power. He was not an ignorant pretender, destitute of practical acquaintance with the requirements of editorial labor, but a man who had himself done all that he required others to do, — and he was respected accordingly.”3

Even Horace Greeley, who often lambasted Raymond while he was alive, wrote after his death that Raymond “was often misjudged as a trimmer and a time server, when in fact he spoke and wrote exactly as he thought and felt.”4 President Lincoln wrote that “The Times, I believe, is always true to the Union, and therefore should be treated at least as well as any.”5 But Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, himself a former newspaper editor, revealed a different opinion of the Times in his diary in June 1864: “The Times is a profligate Seward and Weed organ, wholly unreliable and in these matters regardless of truth or principles. It supports the President because it is the present policy of [Secretary of State William H.] Seward. The principle editor, [Henry J.] Raymond, is an unscrupulous soldier of fortune, yet recently appointed Chairman of the Republican National Committee. He and some of his colleagues are not to be trusted, yet these political vagabonds are the managers of the party organization.”6 In another diary entry, Welles added that the Times “will, under the lead of the Herald, attack any and every member of the Cabinet but Seward, unless Seward through Weed restrains him.”7

John Russell Young, a journalist associated with the newspapers of John W. Forney in Philadelphia and Washington, was an admirer of Raymond: “He was the kindliest of men; he had an open, oxl-like eye, neat, dapper person, which seemed made for an overcoat, a low, placid, decisive voice, argued with you in a Socratic method by asking questions and summing up your answers against you as evidence. ….He was never in a hurry, and yet there was no busier person in journalism. Raymond had the Rouchefoucauld sense of observation, and in conversation you found yourself in presence of a thinker in a constant state of inquiry and doubt. He was a journalist in everything but his ambitions, and those tended to public life…He was conservative. He could not endure a caucus. There was nothing in this world entirely right or entirely wrong, — no peach that did not have a sunny side.”8

Andrew A. Freeman wrote that the Times “in 1860 dominated the newspaper and printing district with a new steam-heated, gaslighted, five-story building.”9 However, the Times did not dominate New York journalism, according to English journalist Edward Dicey. He observed: “The New York Times is, in a literary point of view, a feebler edition of the Herald, without its verve. It is the organ of the moderate Republican party, of whom Mr. Seward and Mr. Thurlow Weed are the leaders in the State of New York; and as this party has never yet been able to look the slavery question boldly in the face, their organ shares in their indecision, and their consequent want of vigor.”10

Raymond “had occasion more than once to display not only moral but physical courage in defense of his principles,” wrote Elmer Davis, in History of The New York Times. “As a reporter and editorial writer he was remarkably gifted; his writing was rapid, his style clear; a rare virtue in those times, his copy was legible.”11 He had been a young assistant of Tribune Editor Horace Greeley and went on to work for the New York Courier and Express before founding the Times in 1851. A Whig activist, he became a Republican stalwart and served as speaker of the New York State Assembly. He was a former Lieutenant Governor of New York, whose nomination to that post in 1854 infuriated Greeley, who thought he had a prior claim to it and who broke off relations with Seward and Weed as a result.

“The editor was a good journalist and the newspaper was a good newspaper, but together they never quite clicked. One of the problems was Raymond’s ambitions for public office; they interfered with his duties at the paper. The other problem, and probably a bigger one, was his dithering; he always had trouble making tough decisions. Maybe it was all part of the fact he was such a political animal,” wrote James M. Perry. “He was the kind of man his rivals loved to poke fun at. They had a field day when Raymond set out to cover the war at Bull Run in person.”12 Unfortunately for Raymond, Army censors prevented most of this reporting from being transmitted back to the New York Times for publication.

Raymond’s moderation was evident during the period after President Lincoln’s election and before his nomination. He wrote Alabama secessionists William L. Yancey: “We shall stand on the Constitution which our fathers made. We shall not make a new one, nor shall we permit any human power to destroy the one….We seek no war — we shall wage no war except in defense of the constitution and against its foes. But we have a country and a constitutional government. We know its worth to us and to mankind, and in case of necessity we are ready to test its strength.”13 Biographer Elmer Davis wrote:

That sentiment guided the editorial course of The Times through the turbulent winter between Lincoln’s election and the attack on Fort Sumter. Raymond deprecated, as all sensible men deprecated, any hasty aggression which might provoke to violence men who could still, perhaps, be brought back to reason; but he insisted that as a last resort the union must be maintained by any means necessary. To the proposals for compromise he was favorable, on condition that they did not compromise the essential issue — that they did not nullify the election of 1860 and give back to the slave power the control of the national government which it had lost. Because no other compromise would have been acceptable the issue inevitably had to be fought out, and from Sumter to Appomattox The Times was unwavering in its support of Lincoln and its determination that the Federal union must and should be preserved.”14

Although his fellow editors might criticize him, none of them showed as much interest in actually visiting the war front as did Raymond. He was present when General Ambrose Burnside went to Washington in January 1863 to protest the behavior of subordinate generals like Joseph Hooker. Raymond went to the White House to plead Burnside’s case. There was a reception going on and Raymond “found a great crowd surrounding Mr. Lincoln. I managed, however, in brief terms, to tell him that I had been with the army, and that many things were occurring there which he ought to know. I told him of the obstacles thrown in Burnside’s way by his subordinates, and especially of General Hooker’s habitual conversation. He put his hand on my shoulder and said in my ear, as if desirous of not being overhead, ‘That is all true — Hooker does talk badly; but the trouble is, he is stronger with the country to-day than any other man.’ I ventured to ask him how long he [Hooker] would retain that strength when his read conduct and character should be understood. ‘The country,’ he answered, ‘would not believed it; they would say it is all a lie.'”15

Such contacts increased Raymond’s influence. Historians Harry. J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin wrote: “For chairman of the Union National Committee, the Baltimore Convention [in June 1864] selected Henry J. Raymond, New York member and editor of the New York Times. Raymond’s selection was a distinct victory for the conservative or Seward-Weed forces over the radical or pro-Chase faction among the Empire State Republicans. Raymond’s Times was the New York City mouthpiece of the Weed interest and as such opposed the radical anti-Lincoln organs, Greeley’s New York Tribune and William Cullen Bryant’s New York Evening Post. Hardly had the Baltimore Convention adjourned than a lively press battle opened between Weed and his opponents.”16

Raymond was allied with Weed and Seward, but he has also once been allied with and employed by Horace Greeley. James M. Perry, himself a 20th Century journalist wrote of Raymond in The Bohemian Brigade: “After graduation [from the University of Vermont], he joined Greeley in New York at the New Yorker, and when Greeley began the Tribune in 1841 he signed on as assistant editor. But, as we have already noted, Raymond was a cautious man and a conservative one, and he was never comfortable with Greeley’s radical and sometimes crackpot ideas.”17 John Waugh wrote in Reelecting Lincoln, “Raymond was a prodigy of sorts. He had begun reading at age three, and had delivered his first speech at five, and his first political speeches on the stump in a presidential campaign at twenty, when he was still too young to vote.”18

According to Waugh: “Raymond was one editor Lincoln could be grateful for. He liked the president, supported him, defended him, wheeled his big, high-toned newspaper along the same policy path — and understood politics so well that he was a leader in Lincoln’s own Republican party, a prominent figure in its birth in 1856.”19 In mid-December 1860, President-elect Lincoln responded to a letter from Raymond that enclosed a letter from a Mississippi resident containing a series of allegations about a September 1859 trip which Mr. Lincoln made to Ohio to make political speeches.

Yours of the 14th. is received. What a very mad-man your correspondent, [Vicksburg, Mississippi resident William C. Smedes is. Mr. Lincoln is not pledged to the ultimate extinctinction [sic] of slavery; does not hold the black to be the equal of the white, unqualifiedly as Mr. S. states it; and never did stigmatize their white people as immoral & unchristian; and Mr. S. can not prove one of his assertions true.

Mr. S. seems sensitive on the questions of morals and christianity. What does he think of a man who makes charges against another which he does not know to be true, and could easily learn to be false?

As to the pitcher story, it is a forgery out and out. I never made one speech in Cincinnati — the last speech in the volume containing the Joint Debates between Senator Douglas and myself. I have never yet seen Gov. Chase. I was never in a meeting of negroes in my life; and never saw a pitcher presented by anybody to anybody.

I am much obliged by your letter, and shall be glad to hear from you again when you have anything of interest.”20

Although Raymond worried about President Lincoln’s policies, he generally supported him. Historian James G. Randall wrote: “An editorial in Henry J. Raymond’s New York Times, endorsed and reprinted in John W. Forney’s Washington Chronicle, described Lincoln in the summer of 1863 as resembling Washington in ‘perfect balance of thoroughly sound faculties,’ ‘sure judgment,’ and ‘great calmness of temper, great firmness of purpose, supreme moral principle, and intense patriotism.'”21 “Balance” was also a description of Raymond himself, according to Elmer Davis: “In his views on public questions Raymond was if anything too well balanced. He often lamented a habit of mind which inclined him to see both sides in any dispute. This may have hampered him as a politician, but on the whole it probably did The Times more good than harm. There were plenty of infuriated and vituperant newspapers in those days, and the success of The Times in the fifties showed that a considerable part of the public approved a measure of temperance in opinions on public affairs. To a certain extent, however, Raymond was really ahead of the time. His attitude toward the problems which led to and arose out of the Civil War, for example, is in almost every detail that which is approved by the judgment of history is so far as that judgment can ever be set down with certainty.”22 John Waugh wrote: “Nobody was certain whether this [balance] was a virtue or not, because it often caused him to temporize, or, as fellow journalist George Alfred Townsend put it: “He was always ditching and diking with his untiring pen’ — rather like McClellan on a battlefield or Lincoln in politics.”23

But Raymond was not balanced in politics. He was a strong Republican with strong views on party loyality. Historian Randall wrote: “When Henry J. Raymond, ‘breathing fire and vengeance,’ demanded the dismissal of certain employees of the New York custom house, who he though had been disloyal to him and to the party, Lincoln refused to comply, saying: ‘I am in favor of a short statute of limitations in politics.'”24

Nor was Raymond unemotional. He played a key role at the meeting of the Republican National Convention in Baltimore in early June. After President Lincoln was nominated on a vote of 507-22, the convention erupted in bedlam. Journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “One of the most comical sights which I beheld was that of Horace Maynard and Henry J. Raymond alternately hugging each other and shaking hands, apparently unable to utter a word, so full of emotion were they.”25

Raymond participated — but with less venom than others — in the Republican newspaper feuds that cut up the party in New York in the months following the 1864 Republican convention. He was furious with the role take by his former boss, Horace Greeley, in the Niagara Falls peace negotiations in mid-July. Historian David E. Long wrote: “When the commissioners’ letter to Greeley hit the front pages [Henry] Raymond exploded. The hypocritical Greeley’s failure to disclose to the Confederates the conditions that Lincoln had insisted upon. Raymond charged, had caused the fiasco. Then when the commissioners blamed Lincoln for the breakdown of the negotiations, ‘Greeley not only failed to relieve him from it by making public the facts, but joined in ascribing to Mr. Lincoln the failure of negotiations for peace and the consequent prolongation of the war.’ Raymond felt there was no limit to Greeley’s perfidy, pointing out that according to Jewett’s statement, Greeley ‘also authorized him to express to the rebel commissioners his regrets, that the negotiation should have failed in consequence of the President’s ‘change of views.'”26

Raymond took a leading role in directing the presidential reelection campaign — especially fund-raising. According to historian James G. Randall: “Federal employees, from the highest to the lowest, were expected not only to work and vote for Lincoln but also to contribute to the Republican campaign chest. The various committees — national, state, and congressional — all gave considerable attention to money-raising activities. ‘Does your State Committee expect to make exclusive assessments upon Federal officeholders within the State for the purpose of the canvass,’ [Henry] Raymond inquired of [Simon] Cameron, ‘or is our Committee to go over the same ground?’ Raymond collected five hundred dollars apiece from cabinet members, directed the assessing of employees in all the departments, and levied ‘an average of three per cent of their yearly pay’ on the workers in the New York Custom House.”27 Raymond used a form letter to solicit funds from government employees and contractors:

Your name, with others, has been handed me as having been employed by the government in furnishing supplies to the medical department of the army during the past year. I take it for granted you appreciate the necessity of sustaining the government in its contest with the rebellion, and of electing the Union candidates in November, the only mode of carrying the war to a successful close, and of restoring a peace which shall also restore the Union.

I trust you will have anticipated the application now made for a contribution to the fund which we need for organizing and carrying on the presidential canvass. The amount of this contribution I of course leave to yourself. Please remit whatever you feel inclined to give in a check, payable to my order as treasurer of the national executive committee. I respectfully ask your immediate attention to this matter, as the need of funds is pressing and the time for using them is short.28

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles was the Administration’s most fervent critic of such fund-raising tactics. Welles wrote in his diary of August 8, 1864:

Mr. Seward sent me to-day some strange documents from Raymond, Chairman of the National Executive Committee. I met R. some days since at the President’s with whom he was closeted. At first I did not recognize Raymond, who was sitting near the President conversing in a low tone of voice. Indeed, I did not look at him, supposing he was some ordinary visitor, until the President remarked, ‘Here he is; it is as good a time as any to bring up the question.’ I was sitting on the sofa but then went forward and saw it was Raymond. He said there were complaints in relation to the Brooklyn Navy Yard; that we were having, and to have, a hard political battle the approaching fall, and that the fate of two districts and that of King’s County also depended upon the Navy Yard. It was, he said, the desire of our friends that the masters in the yard should have the exclusive selection and dismissal of hands, instead of having them subject to revision by the Commandant of the yard. The Commandant himself they wished to have removed. I told him such changes could not well be made and ought not to be made. The present organization of the yard was in a right way, and if there were any abuses I would have them corrected.

He then told me that in attempting to collect a party assessment at the yard, the Naval Constructor had objected, and on appealing to the Commandant, he had expressly forbidden the collection. This had given great dissatisfaction to our party friends, for these assessments had always been made and collected under preceding administrations. I told him I doubted if it had been done,—certainly not in such an offensive and public manner; that I thought it very wrong for a party committee to go into the yard on pay-day and levy a tax on each man as he received his wages for party purposes; that I was aware parties did strange things in New York, but there was no law or justice in it, and the proceeding was, in my view, inexcusable and indefensible; that I could make no record enforcing such assessment; that the matter could not stand investigation. He admitted that the course pursued was not a politic one, but he repeated former administrations had practiced it. I questioned it still, and insisted that it was not right in itself. He said it doubtless might be done in a more quiet manner. I told him if obnoxious men, open and offensive opponent of the Administration, were there, they could be dismissed. If the Commandant interposed to sustain such men, as he suggested might be the case, there was an appeal to the Department; whatever was reasonable and right I was disposed to do. We parted, and I expected to see him again, but, instead of calling himself, he has written Mr. Seward, who sent his son with the papers to me. In these papers a party committee propose to take the organization of the navy yard into their keeping, to name the Commandant, to remove the Naval Constructor, to change the regulations, and make the yard a party machine for the benefit of party, and to employ men to elect candidates instead of building ships. I am amazed that Raymond could debase himself so far as to submit such a proposition, and more that he expects me to enforce it.29

Chairman Raymond didn’t let up. Nine days later, Welles confided to his diary that Assistant Secretary of State “Fred Seward called on me with a letter from Raymond to his father inquiring whether anything had been effected at the navy yard and custom-house, stating the elections were approaching, means were wanted, Indiana was just now calling most urgently for pecuniary aid. I told Seward that I knew not what the navy yard had to do with all this, except that there had been an attempt to levy an assessment on all workmen, as I understood, when receiving their monthly pay of the paymaster, by a party committee who stationed themselves near his desk in the yard and attempted the exaction; that I was informed Commodore Paulding forbade the practice, and I certainly had no censure to bestow on him for the interdiction. If men choose to contribute at their homes, or out of the yards, I had no idea that he would object, but if he did and I could know the fact, I would see such interference promptly corrected; but I could not consent to forced party contributions. Seward seemed to consider this view correct and left.”30

Two days later, Welles recorded: “Seward said to-day that Mr. Raymond, Chairman of the National Executive Committee, had spoken to him concerning the Treasury, the War, the Navy, and the Post-Office Departments connected with the approaching election; that he had said to Mr. Raymond that he had better reduce his ideas to writing, and he had sent him certain papers; but that he, Seward, had told him it would be better, or that he thought it would be better, to call in some other person, and he had therefore sent for Governor Morgan, who would be here, he presumed, on Monday. All which means an assessment is to be laid on certain officials and employees of the government for party purposes. Likely the scheme will not be as successful as anticipated, for the depreciation of money has been such that neither can afford to contribute.”31

Raymond had actually set the tone of his feud with Welles as the Republican National Convention when he called for a new Cabinet — but the target of his speech at that time had been Postmaster General Montgomery Blair. Blair was forced out of the Cabinet three months later in September 1864. Raymond and radicals like Maryland’s Henry Winter Davis sought to obtain removal of Welles and Assistant Secretary Gustavus V. Fox as well. Unlike Congressman Davis, Raymond had access to the President, but was told “he would not do it then, it might be misconstrued.”32

While Raymond was running President Lincoln’s national campaign, he was also running his own campaign for Congress in Manhattan against one Republican and two Democratic candidates. “The campaign was unusually spirited,” wrote Augustus Maverick. “National, State, and local issues…entered into political controversies of the day, and all the lines were sharply drawn. The district in which Raymond ran included the ward which had previously sent him to Albany as its representative in the Legislature; and he alone had the advantage of successful precedent over the candidates against him. His majority over the Mozart (Democratic) candidate, Eli P. Norton, was 5,668; his vote exceeded that cast for the Tammany candidate, Elijah Ward, by 386; the irregular Republican candidate, Rush C. Hawkins, was beaten by a majority of 5,968.”33

With his election to Congress and the death of President Lincoln, Raymond’s political and journalistic careers moved into eclipse. As chairman of the Republican National Committee, Raymond thought it was his duty to support President Andrew Johnson and the National Union Convention in Philadelphia in 1866 that had been called to unite his supporters from the North and South. Raymond’s support cost him his party chairmanship and cost The Times thousands of dollars in subscription revenues.

Footnotes

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 172 (Letter from Edwin D. Morgan to Thurlow Weed (February 9, 1862)).

- Chauncey M. Depew, My Memories of Eighty Years, p. 21.

- Augustus Maverick, Henry J. Raymond and the New York Press for Thirty Years, p. 223.

- Elmer Davis, History of The New York Times, 1851-1921, p. 71.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 360 (Letter to E.A. Paul, May 24, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 87-88 (July 26, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 104 (August 13, 1864).

- James M. Perry, A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents, p. 55.

- Andrew A. Freeman, Mr. Lincoln Goes to New York, p. 70.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Spectator of America: A Classic Document About Lincoln and Civil War America by a Contemporary English Correspondent, Edward Dicey, p. 28.

- Elmer Davis, History of The New York Times, 1851-1921, p. 14.

- James M. Perry, A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents, p. 56.

- Elmer Davis, History of The New York Times, 1851-1921, p. 50-51.

- Elmer Davis, History of The New York Times, 1851-1921, p. 51.

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 235-236 (from Henry J. Raymond, ‘Extracts from the Journal of Henry J. Raymond,’ Scribner’s Monthly, March, 1880).

- Harry J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 262.

- James M. Perry, A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents, p. 56.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 140-141.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 141.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume, IV, p. 156 (Letter to Henry J. Raymond, December 18, 1860).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 367.

- Elmer Davis, History of The New York Times, 1851-1921, p. 14.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 141.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 293.

- Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best, p. 146.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty, p. 124.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 252.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 539.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 97-99 (August 8, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 109 (August 17, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 112 (August 19, 1864).

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 487.

- Augustus Maverick, Henry J. Raymond and the New York Press for Thirty Years, p. 169.