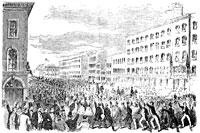

“The closer Lincoln’s train came to Buffalo, the denser grew the crowds,” wrote Victor Searcher in Lincoln’s Journey to Greatness. “Puffing slowly into the Exchange Street depot, the rear car was brought to a stop opposite the main passenger entrance.”1 That night, Albany law student Adoniram J. Blakely wrote his father Dan Blakely: “I have just come in from the throng of the thousands who have been greeting the arrival of Pres. Lincoln. I should judge that the crowd was quite as large as that which was present on the visit of the Prince. The streets & all the steps and windows of the buildings for a distance of more than a mile were densely crowded. And as for getting inside or within twenty rods of the Capitol building it was impossible after the throng had once stationed themselves. Mr. Lincoln looks much wearied & care worn. But his pictures do not do him justice. He is both a smarter & pleasanter looking man than his pictures represent. It was a thrilling scene to see him bowing in his carriage with head uncovered, while the ladies handkerchiefs waived from every window of the long lines of high buildings on each side of the street.2

Henry Villard complained: “The reception in this place was the most ill conducted affair witnessed since the departure from Springfield. A thick crowd had been allowed to await the arrival of the train in the depot so that but a narrow passage could be kept open for the few soldiers and policemen detailed to protect the President-elect. He had hardly left his car and, after heartily shaking hands with Mr. Millard Fillmore, made a few steps toward the door when the crowd made a rush, and overpowering the guard pressed upon him and party with a perfect furor. A scene of the wildest confusion ensued. To and fro the ruffians swayed and cries of distress were heard from all sides. The pressure was so great that it is really a wonder that many were crushed and trampled to death. As it was Major [David] Hunter of the President’s escort alone suffered a bodily injury by having his arm dislocated. The President-elect was safely got out of the depot only by the desperate efforts of those immediately around him. His party had to struggle with might and main for their lives and after fighting their way to the open found some of the carriages already occupied so that not a few had to make for the hotel on foot as best they could. The hotel doors were likewise blockaded by immovable thousands and they had to undergo another tremendous squeeze to get it.”3

The confusion led the Buffalo Express to editorialize: “We cannot cast reflections on the crowd whose action is so much to be regretted…because their conduct was no more than natural, however improper.” The crowd’s conduct “certainly signified no disrespect towards the President-elect, but rather the opposite feelings.”4 John Hay, who had been recruited to work in the Lincoln White House, accompanied the President-elect’s entourage and wrote an anonymous newspaper column about his travels:

The train arrived at Buffalo at 5 o’clock P.M. The crowd at the depot was something unprecedented in the history of popular gatherings in this part of the country. It is estimated that at least seventy-five thousand persons must have participated in the turbulent ceremonials which greeted the arrival of the President elect. The military arrangements, organized with reference to previous gatherings of the sort, were found to be utterly inadequate. As the train rumbled into the great depot — a structure capable of containing at least ten thousand people, the single company on duty, together with a few struggling policeman, were swept away like weeds before an angry current. The crush was terrific. Thousands and thousands of men without, urging, pushing, and struggling, endeavored to force an entrance to the depot, which was already packed to its utmost capacity. The President himself narrowly escaped unpleasant personal contact with the crowd. An intrepid body-guard, composed partly of soldiers and partly of members of his suite, succeeded, however, in protecting him from maceration, but only at the expense of incurring themselves a pressure to which the hug of Barnum’s grizzly bear would have been a tender and fraternal embrace….The President was received by his predecessor, Mr. Fillmore, who uttered the briefest possible words of welcome to the distinguished guest, after which they entered carriages and proceeded in the direction of the American Hotel. The streets were densely thronged, the cheers unremitting, the stars and stripes waved everywhere, from roofs, from windows, from balconies, festoons of drapery, banners with inscriptions of welcome, in fact all the traditionary accessories of popular demonstration were copiously distributed throughout the entire route.On arriving at the hotel, in front of which the throng was so dense that the cortege found it extremely difficult to approach, the President was received by Mayor [A. S.] Bemis in a speech, to which he responded. Immediately upon his entrance the doors of the house were shut in the faces of the crowd. It was only in this manner that the hotel was protected from an incursion, which would have entirely subverted the order of the establishment..5

As usual, Mr. Lincoln tried to avoid saying anything newsworthy. And as usual, he was successful:

I am unwilling, on any occasion, that I should be so meanly thought of, as to have it supposed for a moment that I regard these demonstrations as tendered to me personally. They should be tendered to no individual man. They are tendered to the country, to the institutions of the country, and to the perpetuity of the [liberties of the] country for which these institutions were made and created.Your worthy Mayor has thought fit to express the hope that I may be able to relieve the country from its present–or I should say, its threatened difficulties. I am sure I bring a heart true to the work. (Tremendous applause.) For the ability to perform it, I must trust in that Supreme Being who has never forsaken this favored land, through the instrumentality of this great and intelligent people. Without that assistance I shall surely fail. With it I cannot fail.When we speak of threatened difficulties to the country, it is natural that there should be expected from me something with regard to particular measures. Upon more mature reflection, however, others will agree with me that when it is considered these difficulties are without precedent, and have never been acted upon by any individual situated as I am, it is most proper I should wait, see the developments, and get all the light I can, so that when I do speak authoritatively I may be as near right as possible. (Cheers.) When I shall speak authoritatively, I hope to say nothing inconsistent with the Constitution, the Union, the rights of all the States, of each State, and of each section of the country, and not to disappoint the reasonable expectations of those who have confided to me their votes.In this connection allow me to say that you, as a portion of the great American people, need only to maintain your composure. Stand up to your sober convictions of right, to your obligations to the Constitution, act in accordance with those sober convictions, and the clouds which now arise in the horizon will be dispelled, and we shall have a bright and glorious future; and when this generation has passed away, tens of thousands, will inhabit this country where only thousands inhabit [it] now.6

After the speech, “Mr. and Mrs. Lincoln immediately retired to their private apartments, where they remained till after supper,” wrote Hay. “A deputation, consisting of officers of Governor Morgan’s staff, arrived to-day from Albany, and were received by Mr. Lincoln this evening before the levee. The reception of the public did not differ in any essential particular from those at other cities: the crowd came up one staircase, crossed the corridor bowing to Mr. Lincoln, and descended by another staircase to the street. Occasionally one of the sovereigns would address the President in an informal manner, eliciting always a prompt, sometimes a felicitous, repartee. Several little girls, who were introduced, Mr. Lincoln lifted in his arms and kissed, sending them and their parents away entirely enchanted by his unaffected cordiality. Mrs. Lincoln’s levee, in an adjoining room, was well attended.”7

Hay added: “A committee, representing the German citizens of Buffalo, waiting upon the President during the evening, an attention which he recognized pleasantly in a little speech.”8 Jack Beyer, the former city alderman, who headed the German-American delegation told the President-elect that “we wish you a pleasant and safe journey to the place of your destination and hope that your administration will alike be honorable satisfactory and prove a blessing to the whole nation.” Mr. Lincoln responded: “I am gratified with this evidence of the feelings of the German citizens of Buffalo. My own idea about our foreign citizens has always been that they were no better than anyone else, and no worse. And it is best that they should forget they are foreigners as soon as possible.”9

That night, thousands of area residents and delegations from other New York cities had shown in bitter weather to greet the President at a reception. Hay wrote: “The dining room was crowded. There were elderly women, with umbrellas and spectacles, mounted upon chairs; aged gentlemen, with crutches and benedictions; local politicians, with fluffy white cravats and tremendous appetites; colored persons of both sexes, one or two infants at the breast, together with all the other varieties which make up western life. The dinner was excellent and profuse. At its conclusion Mr. Lincoln was conducted to the balcony and spoke a few words to the assembly, after which the suite formed in line and again entered the cars.”10

Another pre-presidential aide, John G. Nicolay, reported to his fiancé that after a pleasant reception in Cleveland, “We found a disagreeable contrast here. The usual thousands were awaiting our arrival. A little path had been kept open through the crowd, through which we got Mr. Lincoln. The crowd closed up immediately after his passage, and the rest of the party only got through by dint of the most strenuous and persevering elbowing. Major Hunter had his arm so badly sprained that it is doubtful tonight whether he can continue his journey. Arrived at the hotel all was confusion — the committee not only did nothing but didn’t know and didn’t seem to care what to do. We took the matter into our hands and finally arranged pretty much everything. I don’t know when I have done so much work as yesterday, and I am feeling the effect of it to-day….”11

The next day was Sunday, February 17. The New York Herald’s Villard reported: “Mr. Fillmore called at ten A.M. with a carriage for Mr. Lincoln and both attended divine service at the Unitarian church. Dr. Hosmer, the pastor, invoked the blessings of heaven upon the incoming Administration in a most impressive manner, in his opening prayer. All of the congregation were moved to tears. From the church the ex-President and the President-elect rode back to the hotel and were joined by Mrs. Lincoln when the party was driven to Mr. Fillmore’s private residence to partake of a lunch.”12 That evening, President-elect Lincoln was taken by acting Mayor Beemis and former President Fillmore to a meeting at St. James Hall at which Father John Beeson explained his experiences among American Indians and the mistreatment of them which he had witnessed.

Footnotes

- Victor Searcher, Lincoln’s Journey to Greatness, p. 120.

- Harry E. Pratt, Concerning Mr. Lincoln, p. 63 (Letter to Adoniram J. Blakely to Dan Blakely. February 16, 1861).

- Henry Villard, Lincoln on the Eve of ‘61, p. 88-89.

- Victor Searcher, Lincoln’s Journey to Greatness, p. 121 (Buffalo Express, February 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864, p. 33-34 (February 18, 1861).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 220-221 (February 16, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864, p. 34-35 (February 18, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864, p. 34-35 (February 18, 1861).

- Victor Searcher, Lincoln’s Journey to Greatness, p. 126.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press,1860-1864, p. 33.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 28 (February 17, 1861).

- Henry Villard, Lincoln on the Eve of ‘61, p. 90.