The New York draft riots were “a macabre episode, a three-day orgy of violence which sickened Lincoln to read about,” wrote biographer Stephen B. Oates.1 “New York, in its earlier history, stands preëminent among the cities of the country for the frequency and violence of her riots,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt in Leslie’s History of Greater New York. “But up to the year 1863 — with the Doctor’s Mob of 788, the riots of 1834, 1835, 1837, 1849, and the ‘Dead Rabbits’ exploits of 1857, not to mention Mayor Wood’s performances with his ‘own’ police in the same year, all garnishing the record — New York is not easily excelled. In 1863 she added to that record the worst, bloodiest, most destructive and brutal riot of all. It goes by the name of the ‘Draft Riots.'”2

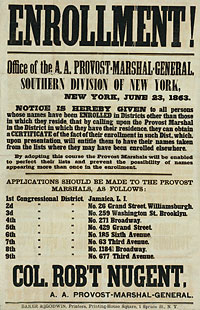

The draft riots stemmed from many causes — not the least of which was the way that violence had been employed for political reasons in the past three decades. But the proximate cause was the fact that New York City — which had furnished too many soldiers to the Union Army at the beginning of the war now furnished too few. Because it was failing to meet its recruitment quotas, it had fallen subject to provisions of the Enrollment and Conscription Act passed by Congress on March 3, 1863. Conscription was to be employed when enrollment targets were not met by a community. “The draft needed to be applied to New York State and city sooner than anywhere else,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt. “At the close of the year 1862, it was reported to the department that since July, 1862, New York State was short 28,517 in volunteers, of which 18,523 was to be charged to New York City. But for this very reason conscription was least likely to be welcomed here. The revulsion in sentiment had carried an anti-war Governor, Horatio Seymour, into office” in 1862.3

Unlike his Republican predecessor, Edwin D. Morgan, Governor Seymour did not construe his job as trying to do everywhere possible to forward troops to the war front. Instead, he quibbled over the accuracy of the War Department statistics. According to Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell, “Governor Seymour was a vigorous opponent of federal conscription, first and last. To begin with, he though the law was unnecessary — which it would have been if all the states had done as well at finding soldiers as New York. In the second place, he though the at evasive and dishonest — as indeed it was. Once it was a law, however, he publicly declared that it would never work and ought to be tested in the courts. This opinion carried him beyond the position of many people who approved his course of conduct as a whole.”4

That set the stage for the bloody and brutal violence of July 14-17, 1863. “The draft riots, as they are called, were supposed by some to be the result of a deep-laid conspiracy on the part of those opposed to the war, and that the successful issue of Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania was to be the signal for open action. Whether this be so or not, it is evident that the outbreak in New York City on the 13th of July, not only from the manner of its commencement, the absence of proper organization, and almost total absence of leadership, was not the result of a general well-understood plot. It would seem from the facts that those who started the movement had no idea at the outset of proceeding to the length they did. They simply desired to break up the draft in some of the upper districts of the city, and destroy the registers in which certain names were enrolled,” wrote Joel Tyler Headley in The Great Riots of New York City.5

The Confederate invasion had contributed to the riots in another way. At the request of the Lincoln Administration, Governor Horatio Seymour had forwarded all available militia units from New York City to the Pennsylvania war front. “George Opdyke, the Republican mayor of New York, protested when he learned that all the troops had been ordered to leave the city for the front, but Major-General [Charles W.] Sandford declared that the governor must be obeyed. Seymour planned to replace the soldiers who had left with militia from the interior of the state, but General Wool requested him to countermand his order to this effect,” wrote Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell.6

New York in 1863 was beset by many problems. “Municipal services failed to keep pace with the rise in population,” wrote William K. Klingaman in Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865. Nearly two-thirds of New York City lacked sewers; many of the sewer lines that existed were so poorly constructed that they frequently were clogged with filth. Epidemics regularly swept through the tenements, giving New York the highest death rate of any city in the civilized world. Merchants sold milk from diseased cattle and coffee tainted with street sweepings and sawdust,” wrote Lincoln chronicler William K. Klingaman.7 But the most important problem in mid-July was the absence of security personnel combined with the presence of angry draft dodgers. The result was an incendiary situation.

“There were murmurings of the coming storm, but efforts to avert it were frustrated by those high in power,” wrote historian Daniel Van Pelt. “Mr. George Opdyke, a Republican, was Mayor, and he foresaw that there would be trouble when the drafts should begin. He remonstrated with Governor Seymour against the withdrawal of all the militia from the city, but the Governor blandly replied that he had to obey superior orders, and that the city would be safe enough under the protection of its own police force.”8 The New York militia had been moved South to help deal with the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg. An important factor in the severity of the riots was their timing. The draft lottery began only a week after the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1-3, 1863. To meet the Confederate invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania, all available militia was sent forward to Pennsylvania when the Confederates invaded the State at the end of June. New York City was not ready to handle the riots.

Footnotes

- Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None, p. 357.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 412-413.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 413.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 313.

- Joel Tyler Headley, The Great Riots of New York City, .

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 301.

- William K. Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865, p. 262.

- Daniel Van Pelt, Leslie’s History of the Greater New York, Volume I, p. 414.

Visit