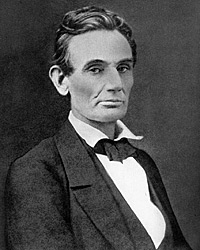

On July 22, 1857, Mr. Lincoln and his wife left Springfield to travel to New York via Niagara Falls, where they stayed at Cataract House until July 24. Little is known of the trip but apparently, the trip was part family vacation and part a business trip to assure payment of the $5000 fee owed by the Illinois Central for Mr. Lincoln’s work on the railroad’s McLean County tax case. Mr. Lincoln had defended the Illinois Central against efforts by McLean County get the railroad to pay taxes on railroad property in McLean — a case which had great implications for the railroad’s finances and profitability. It was a case with great financial importance for the Illinois Central and great personal and financial importance for Mr. Lincoln, who received the largest legal fee of his career for his services.

Mr. Lincoln had offered his services first to McLean County and then to the Illinois Central. He had written a McLean County official, Thompson R. Webber, in September 1853, urging him to unite with Champaign County on the case: “On my arrival here [Bloomington] to court, I find that McLean county has assessed the land and other property of the Central Railroad, for the purpose of county taxation. An effort is about to be made to get the question of the right to so tax the Co. Before the court, & ultimately before the Supreme Court, and the Co. are offering to engage me for them. As this will be the same question I have had under consideration for you, I am somewhat trammelled by what has passed between you and me; feeling that you have the prior right to my services; if you choose to secure me a fee something near such as I can get from the other side. The question in its magnitude to the Co. on the one hand and the counties in which the Co. has land on the other is the largest law question that can now be got up in the State, and therefore in justice to myself, I can not afford, if I can help it, to miss a fee altogether. If you choose to release me; say so by return mail, and there an end. If you wish to retain me, you better get authority from your court, come directly over in the Stage, and make common cause with this county.”1

Failing to be hired by McLean or Champaign Counties, Mr. Lincoln offered his services to Mason Brayman of the Illinois Central: “Neither the county of McLean nor any one on its behalf has yet made any engagement with me in relation to its suit with the Illinois Central Railroad on the subject of taxation. I am now free to make an engagement for the road, and if you think of it you may ‘count me in.'”2 Brayman retained Mr. Lincoln with a $250 check — but no further compensation was forthcoming despite Mr. Lincoln’s successful defense of the railroad before the Supreme Court in early 1856. (Brayman played a recurring part in Mr. Lincoln’s connection with New York City; he socialized with Mr. Lincoln at the Astor House on the day Mr. Lincoln delivered the Cooper Union address in 1861.)

“Up to this point in the discussion of the case writers agree, but in the subsequent details which relate to Lincoln’s efforts to collect his fee they differ widely,” wrote Harry E. Pratt in The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln. “Herndon said Lincoln went to Chicago and presented a bill for $2,000 in addition to the retainer fee. [James F.] Joy, Lincoln’s associate, who had been paid a salary of $10,000 a year by the railroad in 1854, but had resigned soon after, received $1,200 for his services for the case. Joy said Lincoln wrote to him asking that his fee be ‘a particularly beautiful section of land belonging to the company.’ This assertion, made by Joy many years after the trial, is hard to reconcile with Lincoln’s lack of interest in the acquisition of land.”3 Law partner William H. Herndon recalled that after the final decision in favor of the railroad, “Mr Lincoln soon went to Chicago and presented our bill for legal services. We only asked for $2,000 more. The official to whom he was referred, — to have been the superintendent George B. McClellan who afterwards became the eminent general — looking at the bill expressed great surprise. ‘Why, sir’ he exclaimed, ‘this is as much as Daniel Webster himself would have charged. We cannot allow such a claim.'” Herndon said that after this rebuff, Mr. Lincoln consulted with fellow Illinois attorneys who “on learning of his modest charge for such valuable services rendered the railroad, induced him to increase the demand to $5,000 and to bring suit for that sum.”4

John W. Starr wrote in Lincoln and the Railroads: “William E. Curtis, in his ‘True Abraham Lincoln,’ following the lead of Herndon, declares that the bill for $2,000 originally presented, was declined ‘on the ground that it was as much as a first-class lawyer would charge’ which, of course, aroused the indignation of Lincoln. Curtis, however, corrects the impression left by Herndon as to McClellan’s having been the official who snubbed Lincoln. At the time spoken of, 1855, McClellan was in Europe as a Commissioner from the United States Army, and it was not until the beginning of 1857 that he became connected with the Illinois Central Railroad.”5

Historian Starr wrote: “It seems probable that, if there was any snubbing done at that time, James F. Joy, an influential counsel for the railroad, did it. According to Henry C. Whitney, a fellow-attorney of the road, when Lincoln’s bill came in and Joy had to audit it, he disallowed it and spoke contemptuously of Lincoln as a ‘common country lawyer.’ The latter then brought suit in the McLean Circuit Court. The solicitor of the railroad, John M. Douglas, consulted with Whitney about the matter. I said that even if the amount was too large,’ remarks Whitney, ‘we could not afford to have Lincoln as our enemy, instead of an ally,’ on the circuit, and I insisted further that he would beat us anyhow. Douglas paid the fee.”6

When Illinois Central didn’t pay Mr. Lincoln’s bill for $5,000 in a timely manner, Mr. Lincoln filed suit in McLean Circuit Court in the spring of 1857. The railroad declined to settle, but ultimately, according to Pratt, seemed to be persuaded that Mr. Lincoln’s political connections “could do the Illinois Central a great deal of good, or, if he chose, a great deal of harm. This was recognized by the railroad and definite steps, the character of which are not clear, were taken to keep Lincoln’s influence on the side of the railroad.”7

Although the Illinois Central used his services in the spring of 1857, Mr. Lincoln continued the suit in order to persuade the company’s New York-based board of directors to pay him. Mr. Lincoln cited the testimony of six Illinois attorneys that his fee was reasonable. With the concurrence of the railroad’s general counsel, the court agreed to a fee of $4,800 — taking into consideration the earlier retainer fee and a shaky recollection of the precise amount.

Historian Harry E. Pratt wrote: “Lincoln waited a month, but still the fee was not paid. It was, perhaps, with some hope of collecting it that he went to New York city in late July. Disgusted with his reception by the Illinois Central officials, he returned home, and on August 1, an execution was issued to the sheriff of McLean County to seize enough property of the railroad to satisfy the judgment. The fee was then paid. The panic of 1857 struck a month later, and had he not collected when he did it is doubtful if he would have received his money for a considerable time.”8 According to Lincoln’s law partner, William Herndon, “Lincoln gave me my half, and much as we deprecated the avarice of great corporations, we both thanked the Lord for letting the Illinois Central Railroad fall into our hands.”9 Lincoln biographer Albert Beveridge wrote that “the great panic of October, 1857, prostrated business everywhere, all New York banks but one suspended specie payments, as did most financial institutions throughout the country; and on October 9, the Illinois Central Railroad was also ‘forced to suspend payment.'”10

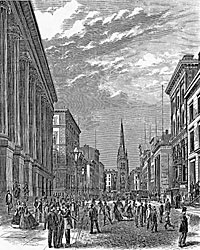

“When Lincoln visited New York for the first time in 1857, the new in New York City was really new,” wrote historian Philip Ernest Schoenberg. “Our city was on the cutting edge of technological innovation, cultural novelty, educational change, financial modernization, transportation leadership, communication pacesetting, commercial pioneering, and cultural trailblazing. For Lincoln, New York was the future, where the rest of America was heading.”11 Schoenberg erred in his characterization of the trip since Mr. Lincoln had clearly been in the city a decade earlier, albeit very briefly. But the city was certainly impressive — especially for Mrs. Lincoln.

The Lincolns were back in Springfield by early August. “The summer has so strangely and rapidly passed away. Some portion of it was spent most pleasantly in traveling East,” wrote Mrs. Lincoln. “We visited Niagara, Canada, New York and other points of interest. When I saw the large steamers at the New York landings I felt in my heart inclined to sigh that poverty was my portion. How I long to go to Europe. I often laugh and tell Mr. Lincoln that I am determined my next husband shall be rich.”12

Footnotes

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 202 (Letter to Thompson R. Webber, September 12, 1853).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 205 (Letter to Mason Brayman, September 12, 1853).

- Harry E. Pratt, The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln, p. 51-52.

- William H. Herndon and Jesse Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 284.

- John W. Starr, Jr., Lincoln and the Railroads, p. 75-76.

- John W. Starr, Jr., Lincoln and the Railroads, p. 75-76.

- Harry E. Pratt, The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln, p. 52-53.

- Harry E. Pratt, The Personal Finances of Abraham Lincoln, p. 54.

- William H. Herndon and Jesse Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 284.

- Albert J. Beveridge, Abraham Lincoln: 1809-1858, Volume I, p. 592-593.

- Philip Ernest Schoenberg, “Lincoln’s New York”, (www.newyorktalksandwalks.com/presidentialexper/stories8.htm).

- Katherine Helm, The True Story of Mary, Wife of Lincoln, p. 122-123 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Emilie Todd, September 20, 1850).

Visit

William H. Herndon (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Henry C. Whitney (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Cooper Union: Before the Speech

Mrs. Lincoln’s Shopping