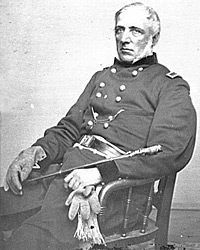

Edwin Morgan

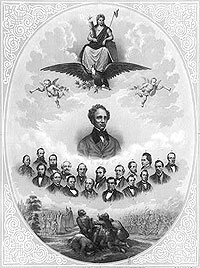

The man of the people! Governor Horatio Seymour

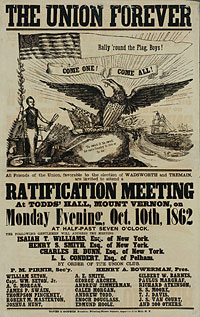

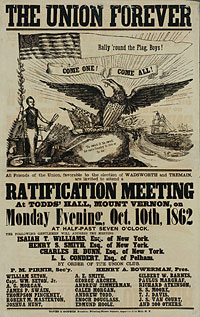

The Union Forever, Ratification Meeting for those favorable to the election of Wadsworth and Tremain

The Old “Gotham” Inn, in Bowery

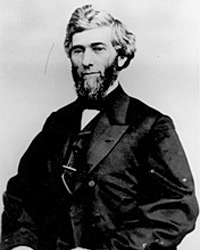

James Wadsworth

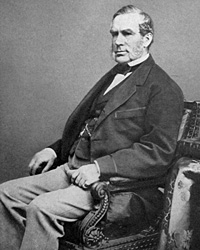

Reuben Fenton

“We at the National Capital are waiting with feverish interest for the returns from your New-York elections. It is impossible to regard otherwise than with the deepest anxiety the position assumed by the people of the most populous and powerful State in the Union. It is not enough that all the rest are right, if New-York is wrong,” wrote presidential assistant William O. Stoddard in an anonymous dispatch for the New York Examiner on November 2, 1862. “The triumphs of the Government supporters in the centre and West will have a hollow sound, if the commercial and financial heart of the nation does not beat full and true. Even a small majority against copperheadism will hardly answer. There must be a complete victory, or even good news from Chattanooga will hardly convince us that the time for rejoicing has fully come. We wait and hope for the best — the very best.”1

Republicans working with War Democrats on a Union ticket had won an overwhelming victory in the 1861. There were efforts during the spring of 1862 to keep the Union effort alive. But Republicans had a difficult time keeping themselves together, much less a larger coalition. They were split by patronage and by differing philosophies on the nature of the war. In addition to patronage, noted historian Sidney David Brummer, “there were three other influences sufficiently traceable and connected more especially with the spring and summer of 1862, which contributed to renewed partisan intensity in New York State. These factors were the reentrance of Thurlow Weed on the political stage, the gradual drift of the Republicans toward emancipation, and the reverses experienced by the Union armies during the summer.”2

Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote: “There is nothing like unsuccessful war to stir up opposition to an administration. So it was in New York. At the same time, however, there immediately followed a series of Union war meetings, throughout the State, in favor of sustaining the government, raising bounties, and encouraging enlistments. These assemblages were addressed to all parties.”3 The irony, Brummer observed was that each party tried to position itself as the true Union party. Brummer noted that “each part in 1862 tried to make the other appear as the one in factious opposition to the national administration. The Union State Committee not only acted with the Republican State Committee in preparing for the fall campaign, but also invited the Democratic and Constitutional Union State Committees to join in calling a convention for the nomination of state officers on the basis of approval of he legislative caucus address and resolutions of April.”4

While Republican leader Weed had been in Europe, Democratic leader Dean Richmond had been trying to put his party back together. “In the early winter of 1862, Dean Richmond flirted with the idea of strengthening Lincoln’s hands in the beginning of the President’s fight to retain executive control,” wrote historian George Milton Fort. But the Democratic detente did not last long. “The war had not been going any too well for the Republican cause, and Dean Richmond grew convinced that the Democrats could elect Horatio Seymour. The latter was reluctant — he never was an eager seeker of nominations, although after his party had put him forward he would fight hard enough for the office. But Richmond set to work to draft him, which he did, with his accustomed skill.”

First, Richmond had a group of former Whigs calling themselves the Constitutional Union Convention, nominate Horatio Seymour or September 9. The next day Seymour was nominated by the Democratic Party.5 Historian Brummer noted: “The idea was to gain for the Democratic ticket the support of the old gentlemen who had once been Silver Gray Whigs. Then too, it permitted the claim to be made that the Democrats had risen above party in accepting as their principal candidate the nominee of another convention.”6 Democrats had also pulled themselves together. Brummer wrote: “The remarkable feature about this convention was its harmony. New York County did not present the rival delegations from Tammany and Mozart, which had distracted Democratic convention after convention. Fernando Wood [of Mozart] and Elijah F. Purdy [of Tammany] had laid aside differences. Their followers had begun to feel the fact that most of the federal, state and municipal patronage was in the hands of the Republicans.”

After Seymour was unanimously nominated and thunderously acclaimed, he gave a speech which set the state for the campaign — which was to be much more about national issues than any state ones. Brummer wrote: “He spoke of the efforts of the Democracy of New York to avert the war, criticised Congress for its violation of the Crittenden resolution, showed how the course of Congress tended to unite the South and divide the North, and help up the Republican press as attacking a Republican administration. Then, he asserted that the Republicans were not fitted to carry on the government. Though not intentionally dishonest and though the party contained loyal men, its leaders were dangerous and unwise. The men in power could not save the country. The Democratic party would continue loyally to support the President and give him all the men he called for to uphold the government, execute the laws, put down the rebellion, and gain an honorable and lasting peace. But that party would not submit to terrorism. The President had been less embarrassed by Democrats than by Republicans. When Seymour had finished, there was another scene of tremendous enthusiasm. Within the narrow partisan position which the New York Democrats had taken, the speech evinced good political leadership, since its criticism of the administration was not tainted by Copperheadism.”7 Seymour had told the convention:

We ask the public to mark our policy and our position. Opposed to the election of Mr. Lincoln, we have loyally sustained him. Differing from the Administration as to the course and the conduct of the war, we have cheerfully responded to every demand made upon us. To-day we are putting forth our utmost efforts to re-enforce our armies in the field. Without conditions or threats we are exerting our energies to strengthen the hands of Government, and to replace it in the commanding position it held in the eyes of the world before recent disasters.”8

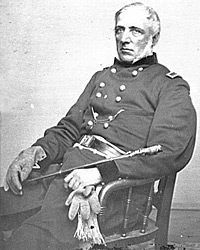

Republican Governor Edward D. Morgan declined to be put forward in 1862. He decided early not to seek reelection. Morgan biographer James Rawley wrote “Perhaps as early as 1861 Morgan had determined not to seek a third term. Late in January 1862 he had told Weed, ‘Nothing whatever is aid about the fall campaign. All are too engrossed in the cares of the present hour to do that. I cannot however but feel that Genl Wadsworth will be willing, and will be far more available than any yet mentioned as my successor.’ Not long after this he wrote his father, ‘…there is a pleasant reflection in doing my duty knowing that my 4 years service as Executive will terminate on the 31st of next December…’ At almost the same time he reported to Weed, ‘It is said that we are going back to Democracy in this State.'”9

Weed returned to New York from Europe on June 5. “To the reentrance of Weed into New York politics can be traced,” wrote historian Sidney David Brummer, “the direction which the differences in the ranks of the administration supporters in this State took. Not that there surely would have been complete harmony had Weed remained abroad. Perhaps the personal rivalries, some evidences of which we have noted in the Legislature of 1862, would have reappeared in the fall convention, even though Weed had not been there. But no division on the question of slavery or on the attitude toward the seceded states had appeared in the Republican ranks during that session. Weed, however was inclined to be a conservative. He had not been able to carry with him his followers of 1861; but his presence in 1862 served to divide the Republicans rather sharply on the question of whether the nominee for governor should be a radical or a conservative.”10

Various reasons have been advanced for Morgan’s decision to step down — dissatisfaction with his administration by Republican radicals, his own disinclination to fight with them, and his desire to move up to the U.S. Senate. “Perceiving the hopelessness of his own cause, Morgan announced he would not be a candidate,” wrote historian William B. Hesseltine.11 Thurlow Weed Barnes wrote:

Deeply impressed with a sense of the importance of sustaining the President and making the war issue so broad as to renew enthusiasm at the North, Mr. Weed sought to secure the renomination of Governor Morgan, who was serving the State so well that history classes him justly with Dennison, Morton, Andrew and Randall, the illustrious ‘War Governors’ of Ohio, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin. Called to the executive station on the 1st of January, 1859, in an era of profound peace, during his incumbency more than 250,000 troops were sent to the front from New York. His term was closing in the midst of a desolating war, but the state debt was actually diminishing. His energy was tireless; his patriotism above question,” wrote Thurlow Weed Barnes.

But during the summer Governor Morgan was opposed with so much bitterness and skill, that when the convention assembled, it was found that he could muster only about one third of the delegates. Mr. Greeley still aspired to the Senate, and Governor Morgan, a resident of New York, was in his way. He therefore urged the nomination of General Wadsworth, a western man, of Democratic antecedents, so that the field for the Senate might remain open.12

Democrats seized the opportunity offered by Republican dissension. Normally, Belmont did not meddle in state politics, but 1862 proved an exception. “When incumbent Republican Edwin D. Morgan declined renomination in order to seek election to the United States Senate, [Democratic National Chairman August] Belmont and leading state Democrats saw an excellent chance to make a comeback. National party committees did not normally ‘interfere’ with the autonomy of state organizations, but the New York Democratic disaster in1860 had been so complete, extending right down to the local level, that Belmont felt it urgent to reconstruct a strong Democratic base there.”13

Historian Allan Nevins put the focus on an upstate boss: “The Democratic strategist Dean Richmond, veteran of a hundred political battles, resolved to make the most of the war weariness. Refusing to listen to a proposal that the Democrats and Republicans unite on John A. Dix, he decided that the ideal candidate was Horatio Seymour, who though only fifty-two had been in public life for thirty years, and had made a creditable governor in 1853-64. This Utica attorney, immersed in his profession and conscious that his sensitive subtle character hardly fitted him to be an opposition leader in a bitter civil war, was reluctant, but the boss refused to take no.”14

The Democrats acted first and ignored Weed’s overtures to nominate a conservative War Democrat. According to historian Nevins “Richmond, coldbloodedly intent on party victory, brought Seymour forward in the most effective way possible. A group of old-line Whigs opposed to emancipation and other radical policies held a Constitutional Union convention in Troy early in September. Here Richmond saw to it that a well-controlled body of delegates effected Seymour’s nomination; and the very next day a Democratic convention in Albany ratified this choice. Party heads could thus assure voters that the Democrats, renouncing partisanship, had accepted the nominee of the Constitutional Unionists, who included Millard Fillmore. The regular Democratic organization was actually in complete control — an organization which Richmond and Seymour would soon dominate more powerfully than any pair since Marcy and Van Buren.”15

The Republican alternative was not as easy to define. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “So strong a nomination demanded an effective counterstroke. Of the two men most discussed for the Republican leadership, James S. Wadsworth and John A. Dix, both had originally been Democrats; but Wadsworth, heir to the greatest landed estate in western New York, had always been sternly antislavery, had helped organize the Free Soil Party, and had become a fullfledged Republican by 1856, while Dix had remained a Democrat, so recognized when Buchanan gave him a Cabinet post and Lincoln appointed him major-general. Wadsworth was fifty-five, Dix sixty-four. While Wadsworth had never occupied a political position and had never even practiced law, Dix had held high offices. Patriotic men might well hesitate between two leaders so able and earnest. But radical Republicans naturally favored Wadsworth, while conservatives preferred Dix. The Greeley-Bryant-Preston King half of the party was aligned against the Seward-Weed-James Gordon Bennett half.”16Historian Sidney David Brummer noted that the Republicans met in convention shortly after President Lincoln issued the draft Emancipation Proclamation. Radical Republicans “accordingly claimed that Wadsworth’s nomination and a resolution in favor of emancipation were necessary to evince support of the President by the party.”17

“It was later said that Weed would have been glad to have had Morgan renominated but that the opposition to the Governor had grown so during the summer that, when the convention assembled it was found that he could get but one third of the votes,” wrote Brummer. “If such opposition existed, it was perhaps due to Morgan’s conservative views, which had recently been manifested in his refusal to participate in the Altoona Conference” of northern Governors concerned over the course of the war.18

Thurlow Weed Barnes wrote: “When it was plain that Governor Morgan could not be renominated, Mr. Weed suggested other Republicans, as brave and deserving as General Wadsworth, but more conservative. Rejecting all such propositions, the convention nominated the radical candidate by acclamation. Mr. Weed then insisted that the ticket should be ‘ballasted,’ by yielding the selection of Lieutenant-Governor to the minority. But the Radicals were inexorable. Rejecting R. M. Blatchford, James M. Cook. W.E. Leavenworth, and other Republicans of Whig antecedents, put forward by Mr. Weed, the convention named for Lieutenant-Governor, Lyman Tremaine, another Democratic-Republican, who less than six months before had made a Copperhead speech at a Democratic mass-meeting in Albany. So as to ‘drive the nail home,’ the convention concluded its labors by appointing a state committee from which ‘Weed men’ were carefully excluded. The headquarters of the party were then moved from Albany, to New York….”19

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, himself a former Democrat, wrote in his diary: “There has been a good deal of peculiar New York management in this proceeding, and some disappointments. Morgan, who is, on the whole, a good Governor, though of loose notions in politics, would, I think, have been willing to have received a third nomination, but each of the rival factions of the Union party had other favorites. The Weed and Seward class wanted General Dix to be the conservative candidate, — not that they have any attachment for him or his views, but they have old party hate of Wadsworth. The positive Republican element selected Wadsworth. It is an earnest and fit selection of an earnest and sincere man. In bygone years both Wadsworth and Dix belonged to the school of Silas Wright Democrats. It would have been better had they (Seward and Weed) taken no active part. I am inclined to believe Weed so thought and would so have acted. He proposed going to Europe, chiefly, I understand, to avoid the struggle, but it is whispered that Seward had a purpose to accomplish, — that, finding certain currents and influences are opposed to him and his management of the State Department, he would be glad to retreat to the Senate.”20

The result of the 1862 Republican convention demonstrated that Weed no longer controlled the state Republican organization. “The Republican convention, meeting two days later in Syracuse, was a complete triumph for the radical wing,” wrote historian Allan Nevins. “In the atmosphere produced by Lincoln’s proclamation, any other outcome would have been a repudiation of his policy. Raymond of the Times, chosen to preside, told the delegates that he favored Dix because his chats with politicians had convinced him that Wadsworth could never be elected, and the War Democrats attending the convention shared this view. On the first ballot, however, Wadsworth received the nomination, and the convention tailored a platform to suit him, hailing emancipation and urging a relentless prosecution of the war. Bryant’s son-in-law Parke Godwin was head of the resolutions committee, and Bryant and Greeley were exultant. Both had often said that slavery was the deadly foe of the nation and Wadsworth typified the determination to crush it.”21

In the Republican convention, John Dix had received 110 votes — compared to 234 votes for Wadsworth and 34 votes for Lyman Tremaine, a War Democrat who was eventually named as the candidate for Lieutenant Governor. “This was a further blow to Thurlow Weed, since neither of the two principal nominees came from that wing of the party which was composed mainly of former Whigs, despite the fact that several names of men of such antecedents were put forth by Weed,” wrote historian Sidney Brummer.22

Historian Brummer wrote: “In his letter of acceptance, Wadsworth declared that he entirely approved of the Emancipation Proclamation, and commended it to the voters of New York as an effectual, speedy, and humane way of subduing the rebellion. He asserted that the war had proved that the fears of black insurrections were without foundation, and the emancipation once accomplished, the North would be relieved from any danger of a great influx of African laborers to compete with whites, while the negro population already in the North would ‘drift to the South where it will find a congenial climate and vast tracts of land…'”23

Wadsworth biographer Henry Greenleaf Pearson wrote: “The nomination of Wadsworth was received with enthusiasm and his election regarded as certain. In his letter of acceptance and in a speech to a group of serenaders who came to his house, Wadsworth indicated in unequivocal terms his position on Emancipation and the prosecution of the war. Having put himself publicly on record, he declared that military duties prevented his leaving Washington to stump the State; the campaign must go on without help from him.”24 It was obvious that Wadsworth’s participation in the campaign wasn’t expected and Weed’s participation wasn’t wanted. Thurlow Weed Barnes wrote: “Mr. Weed went to New York, shortly afterward, for the purpose of conferring with the committee, in session at the Astor House. Somewhat to his chagrin, he was informed by James Kelly, an accredited delegate, that his presence and cooperation could be dispensed with. Mr. Weed’s room in the hotel was directly opposite the Republican headquarters.”25

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in his diary in early October 1862: “Had a long interview with Governor Morgan on affairs in New York and the country. He says Wadsworth will be elected by an overwhelming majority; says the best arrangement would have been the nomination of Dix by the Democrats and then by the Republicans, so as to have had no contest. This was the scheme of Weed and Seward. Says a large majority of the convention was for renominating him (Morgan). I have little doubt that Weed and Seward could have made Morgan’s nomination unanimous, but Weed intrigued deeper and lost. He greatly preferred Morgan to Wadsworth, but, trying to secure Dix, lost both.”26

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The campaign was inevitably tinged by bitterness. Seymour in his convention speech had thrown down a gage which the Republicans were quick to catch up. Greeley indulged in an orgy of villification, and even the mild Henry J. Raymond declared that a vote for Seymour was a vote to destroy the Union. According to the Tribune Seymour was hand in glove with men openly hostile to the war. Actually, copperheadism at this time was weak except in New York City, and the great mass of voters demanded an earnest continuance of the struggle; but some excited upstate editors were almost as vitriolic as Greeley.”27

Seymour attempted to stay above the political battles. Allan Nevins wrote: “Seymour and the Democrats relied largely upon the Constitution in their campaign. While Wadsworth ostentatiously remained at his post of duty, Seymour harangued the citizens on the evils of arbitrary arrests and the Emancipation Proclamation. The latter was ‘a proposal for the butchery of women,’ for ‘arson and murder,’ for ‘lust and rapine.’ Moreover, Seymour assured the electorate, the Democrats had no desire to embarrass Lincoln — they only wanted to bring Washington to a realization that the war was solely for the suppression of the rebellion. It was not fought to change the social system of the states.”28

According to Wadsworth biographer Henry Greenleaf Pearson, “Almost immediately, however, it became plain that there was to be a lively contest. Seymour and his followers began a series of partisan attacks on the administration. Emancipation was condemned as ‘a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, and of arson and murder, which would invoke the interference of civilized Europe.’ Corrupt contracts and arbitrary arrests were violently denounced. To these attacks Raymond, in the New York Times, and Greeley, in the Tribune, made vigorous reply. On both sides the blows were shrewd and in the heat of the strife personalities were soon mingled with policies as the subject-matter of debate. Wadsworth’s record as land-owner and soldier was vilified with abundant use of superlatives; the polls, it was said, was the only place where this general would not run well. ‘Prince John’ Van Buren, appearing from retirement to delight audiences with his wit, and to anger opponents by his misrepresentation. As sometimes happens when men who have been friends become political opponents, he forgot to fight fair, and ridiculed Wadsworth’s military career as insignificant — that of a mere militia major.’ Wadsworth was also attacked for his alleged interference with McClellan’s plans; on the other side, Seymour was made to smart from repeated accusations of treason. The intensity of the conflict, all the sharper because the contestants stood at the extremes of the two parties, at last began to alarm Republicans and Democrats occupying the middle ground where, according to the proverb, the way is safest. Fearing not only defeat in the election but party disruption as well, some of them now urged that both candidates should withdraw in order that General Dix might take the field alone. Even those who proposed the scheme must have realized that there was little hope of its success; and when the sturdy old soldier replied that he could not leave his post at Fortress Monroe ‘to be drawn into any party strife,’ they resigned themselves to party strife again.” 29

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “So disruptive did the campaign become that some frightened men tried to get both Seymour and Wadsworth to retire in favor of a new coalition of moderates under Dix. Bennett’s Herald, which had opposed Wadsworth, on October 13 vainly urged Seymour to use a great meeting that night in Cooper Union to surrender his place to Dix. General Wadsworth did not appear in the State until October 30, when he arrived in the metropolis to address a mass meeting.”30

“Seymour, after his first harsh speech, conducted his battle on a high plane. Fully aware of his responsibilities, he emphasized his loyalty to the Union, spoke of Lincoln respectfully (protesting, indeed, against abuse of him), and founded his appeal primarily on the failure of Republicans to save the country. The victorious Democrats, he promised, would give Lincoln fuller support than radicals like Chase and Wadsworth. Democratic victory, moreover, would bring the Administration back to the right track — the crushing of the rebellion, as distinguished from the overthrow of the Southern social system — and thus reduce the danger of foreign interference. But some of Seymour’s supporters were wildly intemperate, declaring that Northern boys were being killed merely to satisfy antislavery fanatics. Bennett in the Herald, for example, predicted that if Wadsworth were elected, he would inaugurate a reign of terror worse than anything since the French Revolution — for his acts while commander in Washington proved it. On the Republican side, Weed and Seward remained chilly, and a letter Seward finally sent in behalf of Wadsworth disgusted Charles Sumner by its feebleness. We need a bugle note, he snorted, and Seward gives us a riddle!”31

But the bitterness of the gubernatorial campaign continued to escalate — as it was defined as a test of loyalty and civil liberties — which were particular pointed issues since many of those arrested by military authorities were held at Fort Lafayette in New York. The Times‘ Henry J. Raymond attended a Republican meeting at which a resolution was passed that a vote for Seymour was a vote for treason.32 Customs official Henry B. Stanton proclaimed that “the scope and drift of the policy maintained by Horatio Seymour and Fernando Wood is to give aid and comfort to the Rebels and to cripple the Administration in a vigorous prosecution of the war.”33 War Democrat Daniel S. Dickinson denounced Seymour for his silence “on the subject of denouncing the Rebellion.”34 The formula advanced by the New York Tribune was simple. It said that every support of the “Slaveholders’ Rebellion is a support of Seymour. Every voter that asserts that the Southern Rebellion was provoked and all but justified by Northern Aggression is for Seymour.”35 A week later, Tribune Editor Horace Greeley was even more forceful: “They lie — consciously, wickedly lie, — who tell you that to support Seymour, Wood and Co., is the true way to invigorate the prosecution of the war…”36

Seymour tried to refute these allegations with prolific protestations of patriotism. He told a Cooper Union meeting in mid-October: “”Now let me say this to the higher law men of the North, and to the higher law men of the South, and to the whole world…that this Union never shall be severed, no, never. Would that my voice could be heard through every Southern State, and I would tell them their mistake.”37 Seymour charged in a separate speech that “the men who denounce you and me as being untrue to the institutions of the country…have been foremost in every measure calculated to embarrass the government, and to hinder and retard the successful prosecution of the war.”38 But attorney George Templeton Strong saw the election as a clear test of patriotism, writing in his diary: “I hope Wadsworth and the so-called radicals may sweep the state and kick our wretched sympathizers with Southern treason back into the holes that have sheltered them for the past year and from which they are beginning to peep out timidly and tentatively to see whether they can venture to resume their dirty work.”39

Seymour tried to make the infringement on civil liberties a central issue of his campaign. ‘Seymour condemned the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus by the President, and attacked the doctrine that freedom of speech in the loyal states was to be restrained because there were disloyal states in the South,” wrote historian Brummer.40 Former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson replied to the Democratic line of attack: “A war of rebellion is a fearful and alarming reality, and is neither to be run away from nor quieted by reciting boarding-school homilies….The course of the President in arresting spies and the apologists of rebellion — in suppressing treasonable presses — in suspending the writ of habeas corpus….entitles him to the admiration and thanks of every good citizen. Let assassins whet their knives — let spies and traitors and pimps and informers scowl and gibber and whisper discontent because the ‘freedom of speech’ is abridged — let conspiracy and treason plot at their infernal conferences — let politicians scheme and elongate and contract their gum-elastic platforms to suit emergences, and when all this has been done the action of the President in these measures, though probably not free from mistakes and errors, will be approved by honest men and in the sight of Heaven, and will, when rebellion shall only be remembered for the blood it has shed and the wrongs it has perpetrated,’ stand the test of talents and time.”41

Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote: “General Wadsworth remained conspicuously absent at the front all during the campaign of 1862; so Seymour exchanged the compliments of debate chiefly with old ‘Hards’ like [Daniel S.] Dickinson and [Lyman] Tremaine, not barnburners like [John A.] Dix. The Democratic candidate was effectively adroit in pointing out how absurd it was for him to be called a traitor by the very men who had not only voted for Breckinridge in 1860 but sat on the platform of Tweddle Hall during the first days of secession.” He reminded the public that many of the most furious foes of secession had broken up abolition meetings in the days before the Civil War, and had even heckled one in a church in Utica against this own protest. He did not deny to a man who had once been a pro-slavery Democrat the right to change his mind, but he felt that honest ‘penitence should make men modest, not abusive.’ The radicals had much to answer for, also; it was their meddling and intrigue which had demanded the removal of McClellan and brought on a series of disastrous defeats.”42

Wadsworth biographer Henry Greenleaf Pearson wrote: “The managers of Wadsworth’s campaign, perceiving that the party was likely to suffer from lukewarm allegiance as well as from active opposition, arranged for a mass-meeting at Cooper Institute, in New York City, on the evening of October 30, a few days before the election, and put before Wadsworth with all urgency the need of his attendance. Heeding their importunities, he obtained leave from his duties in Washington and came.”43

It was only five weeks after President Lincoln had issued the draft Emancipation Proclamation when Wadsworth came to New York City to give his sole speech of the campaign. Wadsworth, a longtime critic of General George B. McClellan, was already under attack by the Albany Argus as “one of the assassins of McClellan.”44 Thurlow Weed was once again in the city, “when his friend Wakeman informed him that General Wadsworth was expected in the city, and had been invited by the committee to speak at a Republican ratification meeting,” wrote Thurlow Weed Barnes. “When General Wadsworth arrived shortly afterwards, he walked into Mr. Weed’s room, who, as he entered, said: ‘James, for the first time in my life, I am not glad to see you,’ adding, in explanation, ‘you have been sent for to make an abolition speech. You will do it, and thus throw away the State.’ Mr. Weed then urged the General to discard the advice of the committee; tell the people what the army had done, was doing, and hoped to do; denounce Vallandigham and other disloyal Democrats; leave the slavery question to take care of itself, and appeal to the friends of the Union, irrespective of politics, to rally in defense of the government. The meeting was held and General Wadsworth made an abolition speech.”45 Historian William B. Hesseltine wrote that “Weed advised him to speak for Lincoln and the Union but Wadsworth’s principles were sounder than his judgment. He would have none of such ‘infamy.’ ‘We have paid for peace and freedom in the blood of our sons,’ he said, ‘let us now have it.'”46

Most New York voters at the time were moderates. Historian Sidney David Brummer wrote that “Copperheadism was very weak at that time in New York State. The great mass of the voters were, in 1862 at least, heartily in favor of supporting the war.”47 According to Brummer: “That which gave some foundation to the accusations of the Republican-Unionists was the disloyal utterances of such Democrats as the two Woods[Fernando and Benjamin], the vagueness of the plans of the Democrats for attaining peace, and the very fact that they persisted in maintaining a partisan opposition in the midst of so great a contest, when parties meant division at the North and a consequent weakening of the efforts to suppress the rebellion.”48

Republicans associated with Thurlow Weed wanted to tap into the strong vein of Union sentiment without unleashing the less favorable feelings about ending slavery. They did not want to make the campaign about President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. “Conservative Republicans were shivering in anticipation, for they knew, as Weed said later, that he would make an emancipationist speech which might throw away the State. All efforts to persuade him to confine his remarks to Lincoln and the Union met a peremptory rejection,” wrote historian Allan Nevins.49 “The climax of the campaign brought the contestants together at Cooper Institute a few days before election. At the beginning of the contest the radical managers had rejected Thurlow Weed’s practical and experienced advice. But as the campaign went badly, they had invited him to their councils. Weed raised money and did what he could to revive the hopeless cause,” wrote William B. Hesseltine.50 Weed’s grandson wrote later: “Dismayed at the prospect, the radical managers finally implored Mr. Weed’s assistance. They had been unable to raise funds. He sent for Abram Wakeman, James Terwilliger, and other zealous party workers, through whose vigorous efforts, at the eleventh hour, the Republican candidate fell only 11,000 votes behind his Democratic competitor.”51

Historian Hesseltine wrote that General Wadsworth’s speech had ‘fervor without poise, passion without compromise.”52 Wadsworth’s speech was a turning point in the election — most observers thought it alienated enough moderate-conservative voters to allow Seymour to win. It was a strong defense of Lincoln Administration policies and a strong attack on Peace Democrats. Wadsworth told the crowd:

You hear it charged by my opponents that our national administration is incompetent to manage the affairs of the country in this crisis. I do not propose to enter into an elaborate defence of the administration. I am not of the administration; I am only its subordinate officer, its humble and, I trust, its faithful servant. [Great applause.] Look, for a moment, at the circumstances under which this administration took up the reins of power. James Buchanan [murmurs of indignation] and the thieves and traitors who gathered around him had left the country a hopeless wreck, almost in the struggle of death. Under these trying circumstances, Abraham Lincoln [enthusiastic applause], an able, honest inexperienced man, came to the aid of the government. I do not doubt that his warmest friends, and the warmest friends of his cabinet officers, will admit that mistakes have been committed — and considerable mistakes; but that they have labored faithfully and earnestly to sve this country, I can myself bear witness. [Applause.] And I do not believe that even in this heated canvass any man has dared to stand up before you and say that Abraham Lincoln was not an honest man, trying to save his country. What do these gentlemen propose? Do they intend to supersede the administration by a revolution? The more audacious among them have dared to hint it. If they dared openly to avow it they would be covered with infamy, and would not receive one in a thousand of the votes which will now be given by unreflecting men for their ticket. Does it need argument to prove that if this rebellion is put down at all it must be done within the two years and a few months during which Mr. Lincoln must administer the government?

What, then, can any honest patriot, whose heart looks alone to the preservation of his country, do to sustain and strengthen Abraham Lincoln? Advise him; admonish him, if you will — and I tell you no man receives the plain talk of honest men, whether political friends or opponents, with more pleasure and more courtesy than Abraham Lincoln — admonish him, if you will, but strengthen and sustain him. [Applause.] Give him your lives and fortunes and sacred honor to aid his honest efforts to put down this rebellion, and I venture to promise that before the end of his term the sun will shine upon a land unbroken in its territorial integrity [applause], undiminished in its great proportions, a land of peace, a land of prosperity, a land where labor is everywhere honorable and the soil is everywhere free. [Great applause.]

Mr. Lincoln has told you that he would save this country with slavery if he could, and he would save it without slavery if he could; he has never said to you that if he could not save slavery he would let his country go. [Applause.] I believe that honest patriot[s] would rather be thrown into a molten furnace than utter a sentiment so infamous. He has said to those in rebellion against the United States: ‘I give you one hundred days to return to your allegiance; if you fail to do that, I shall strike from under you that institution which some of you seem to think dearer than life, than liberty, than country, than peace.” And some of us, let me add, appear to entertain the same opinion. Gentlemen, I stand by Abraham Lincoln. [Tremendous applause.] It is just, it is holy so to do. I ask you to stand by him and sustain him in his efforts. [We will; we will.]

I know, for I have sometimes felt, the influence of the odium which the spurious aristocracy, who have so largely directed the destines of this nation for three-quarters of a century, have attached to the word ‘abolition.’ They have treated it, and too often taught us to treat it, as some low, vulgar crime, not to be spoken of in good society or mentioned in fashionable parlors. I know there are many men still influenced by this prejudice; but let those who, in this hour of peril, this struggle of life and death, shrink from that odium stand aside. The events of this hour are too big for them. They may escape ridicule, but they cannot escape contempt. Their descendants, as they read the annals of these times and find the names of their ancestors nowhere recorded among those who came to the rescue of their government in the hour of its greatest trial, will blush for shame. [Applause.]

You are told by the candidates of this anti-war party which is springing up that they will give you peace in ninety days. I believe them. They will give you peace — but, good God, what a peace! A peace which breaks your country into fragments; a Mexican peace; a Spanish-American peace; a peace which inaugurates eternal war! [Applause.] What peace can they give you in ninety days or in any other time which does not acknowledge the Southern Confederacy and cut your country in twain? Let me ask you, for a moment, if you ever looked at the map of your country which it is proposed to bring out — this new and improved map of Seymour, Van Buren & Co., the map of these ‘let ’em go’ geographers? [Laughter.] A country three thousand miles long, and a few hundred miles wide in the middle. Why, they could not make such a country stand until they got their map lithographed; nay, not even until they got it photographed. [Renewed laughter.] All the great watercourses, all the great channels of trade dissevered in the middle. No, the mandate of nature, the finger of God is against any such disseverance [sic] of this country. It can never be divided by the slave line or any other line.

If you are not prepared to acknowledge the independence of the Southern Confederacy and take this peace which is offered to you in ninety days, what are the other alternatives presented to you? The South has unanimously declared that she will submit to no restoration of the Union, that she will under no circumstances come back into the Union. What, then, are we to do? We must either go over and join them and adopt their laws and their social system, or must subjugate them to our laws and to our system. Abraham Lincoln tells you that he intends to subjugate them. Your soldiers in the field say that they intend to subjugate them. [Applause.] Sleeping to-night upon the cold ground as they are, to sleep to-morrow, perhaps, upon the battlefield, to sleep in death forever, they say: “Surrender never!” [Great applause.] Gentlemen, what do you say? Do you propose to surrender? [No, no, never!] What is to be the voice of New York upon this question. Is it to carry cheering words to those brave and suffering soldiers? Is it to reanimate and encourage them? Or is it to tell them that their State is against men who were not in any sense political partisans gave careful heed to his words. He stood for achievement. He brought the great struggle near home, and men listened as to one with a message from the field of patriotic sacrifices. The radical newspapers broke into the chorus of applause. The Radicals themselves were delighted. The air rung with praises of the courage and spirit of their candidate, and if here and there the faint voice of a Conservative, suggested that emancipation was premature and arbitrary arrests were unnecessary, a shout of offended patriotism drowned the ignoble utterance.”53

Wadsworth’s speech exposed one of the two sets of issues on which the Republican ticket was perceived to be vulnerable — abolition and emancipation. New York attorney George Templeton Strong expounded on the second set — arbitrary arrests and violations of civil liberties — in a diary entry a few days before the election: “Alas for next Tuesday’s election! There is danger — great and pressing danger — of a disaster more telling than our Bull Run battles and Peninsular strategy: the resurrection to political life and power of the Woods, Barlows, LaRocques, and Belmonts, who had been dead and buried and working only underground, if at all, for eighteen months, and everyone one of whom well deserves hanging as an ally of the rebellion. It would be a fearful national calamity. If it come, it will be due not so much to the Emancipation Manifesto as to the irregular arrests the government has been making. They have been used against the Administration with most damaging effect. And no wonder. They have been utterly arbitrary, and could be excused only because demanded by the pressure of an unprecedented national crisis; because necessary in a case of national life or death that justified any measure, however extreme. But not one of the many hundreds illegally arrested and locked up for months has been publicly charged with any crime or brought to the notice of a Grand Jury. They have all been capriciously arrested, so far as we can see, and some have been capriciously discharged; locked up for months without legal authority and leg out without legal acquittal. All this is very bad — imbecile, dangerous, unjustifiable. It gives traitors and Seymourites an apology for opposing the government and helping South Carolina that it is hard to answer. I know it is claimed that these arrests are legal, and perhaps they are, but their legality is a subtle question that government should not have raised as to a point about which people are so justly sensitive.”54

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The real stake in the New York contest, it seemed to many, was national power. Behind the mask of Wadsworth, conservatives of both parties saw the sinister figure of Chase, archenemy of Seward and of moderate policies; already staggered by the Republican defeat in Ohio, the Secretary must not be allowed to triumph in the Empire State. Not only Seward, but Montgomery Blair and Bates, were believed to be at heart against Wadsworth, and it is certain that Thurlow Weed was lukewarm if not disloyal in the Republican cause. Bennett’s Herald, professedly for Lincoln and the Union, exerted all its influence to help elect Seymour. On the Democratic side, efficient city machines for once worked in unison. The Mozart Hall Democracy and Tammany Democracy had made a bargain which ensured Fernando Wood, and his brother Benjamin Wood of the Daily News, James Brooks of the Express, and Anson Herrick of the Atlas seats in Congress; these three newspapers gave stanch support to each other, while the halls united with the Albany Regency in forming a solid front behind Horatio Seymour. McClellan could hardly contain his hatred for Wadsworth. ‘I have so thorough a contempt for the man and regard him as such a vile traitorous miscreant that I do not wish the great State of New York disgraced by having such a thing at its head.'”55

Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell noted that Greeley considered Wadsworth his candidate and thought that “if he could elect him, he would have his deputy as governor in Albany at last. He laid the failure of his fine plan to a general conspiracy. He publicly accused Weed of treachery, for one thing.”56Thurlow Weed sought to defend himself against such charges that he had abandoned the Republican candidate. He wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Commercial Advertiser in which he declared: “The friends of Governor Seward,’ generally, are cordially supporting the Union State ticket….While it is true that I urged upon the Union State Convention the nomination of General Dix, I have, from the moment General Wadsworth was nominated, given him and our whole State ticket my stead and earnest support.”57 Mitchell cites as evidence for Weed’s Seymour sympathies a speech on October 22 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music “which gained for Seymour the subsequent blessing and good will of Thurlow Weed. The peroration of that speech was prepared in substance by none other than Samuel Jones Tilden. Thus when he spoke at Brooklyn, Seymour expressed the sentiments of a lifelong Whig, a famous Van Buren Barnburner Democrat, and presumably himself. Shortly after Seymour’s election, Weed wrote to him as follows: “If I go away without seeing you, le me entreat you to use the power and position the people have confided to you in such a way as will promote the interests of our whole country, and make your name illustrious and your memory blessed. Your Brooklyn speech contains all that is needful. Only stand by it, and our government can be preserved.”58

Attorney Strong wrote in his election eve diary: “Tomorrow’s prospects bad. The Seymourites are sanguine. Vote will certainly be close. A row in the city is predicted by those who desire one, but it is unlikely, though people are certainly far more personally bitter than at any election for many years past. A Northern vote against the Administration may be treated by Honest Old Abe as a vote of want of confidence. He may dismiss his Cabinet and say to the Democrats, ‘Gentlemen, you think you can do this job better and quicker than Seward and Chase. Bring up your men, and I’ll set them to work.’ It would be like him. And there is little to choose between the two gangs. After all, Seymour and his tail want the offices — public pay and public patronage. As governor, Seymour will probably try to outbrag the Republicans in energetic conduct of the war. He cares more for his own little finger than for all the Body Politics, and will be as radical as Horace Greeley himself whenever he can gain by it.”59

Seymour carried the state by 11,000 votes — compared to the 50,000 vote edge that both Governor Morgan and Mr. Lincoln had enjoyed two years earlier. “To the Radicals, confident in the righteousness of their cause and looking so far ahead to the time of its ultimate consummation that their vision of immediate conditions was distorted, the result of the election was nothing short of astounding,” wrote Wadsworth biographer Henry Greenleaf Pearson. “Seymour had a majority of over ten thousand votes. Thereupon ensued much discussion between the wings of the Union party as to the cause of the defeat, each side considering that it had a grievance against the other. According to H. B. Stanton, the anti-slavery journalist, Wadsworth believed that Seward was dead against him all through the campaign.”60 The anti-Weed faction blamed Weed. The Weed faction thought he had been frozen out of the campaign. The anti-Weed faction thought he had frozen himself out.

The election results deeply depressed George Templeton Strong: “As anticipated, total rout in this state. Seymour is governor. Elsewhere defeat, or nominal success by a greatly reduced vote. It looks like a great, sweeping revolution of public sentiment, like general abandonment of the loyal, generous spirit of patriotism that broke out so nobly and unexpectedly in April, 1861. Was that after all nothing but a temporary hysteric spasm? I think not. We the people are impatient, dissatisfied, disgusted, disappointed. We are in a state of dyspepsia and general, indefinite malaise, suffering from the necessary evils of war and from irritation at our slow progress. We take advantage of the first opportunity of change, for its own sake, just as a feverish patient shifts his position in bed, though he knows he’ll be none the easier for it. Neither the blind masses, the swinish multitude, that rule us under our accursed system of universal suffrage, nor the case of typhoid, can be expected to exercise self-control and remember that tossing and turning weakens and does harm. Probably two-thirds of those who voted for Seymour meant to say by their votes, ‘Messrs. Lincoln, Seward, Stanton & Co., you have done your work badly, so far. You are humbugs. My business is stopped, I have got taxes to pay, my wife’s third cousin was killed on the Chickahominy, and the war is no nearer an end than it was a year ago. I am disgusted with you and your party and shall vote for the governor or the congressman you disapprove, just to spite you.”61

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The November elections gave the New York Democrats a decisive victory. Seymour had a majority of nearly 11,000, and the Democrats won 17 Congressional seats, the Administration only 14. Roscoe Conkling, Lincoln’s brilliant young supporter in the House, lost his place. Though weariness, Republican disunity, and resentment over arbitrary arrests all counted in the result, here the major explanation lay simply in the military reverses. Bryant had written Lincoln just before the election that Seymour’s election, ‘a public calamity,’ might be averted if the armies would only win a timely battle, but that continued military inactivity would lose New York and other States. And [former Democratic Congressman] John Cochrane later wrote Lincoln that the adverse vote expressed not hostility to him, but disappointment in the dragging war.”62 According to Cochrane:

The returns from the City are overwhelming our cause. Those from the Country will not restore the battle and we shall be beaten by about ten thousand— I have no doubt that in the other States with one exception or two here & there the same result will be seen— I do not think that the majorities have spoken designedly upon any one subject in hostility to your administration— Some have been adverse to the proclamation — others have been impelled by some uncertain indefinite sense that all was not right: and the greatest numbers have greedily visited their disappointment that the war is not finished & was not finished in 60 days upon the first responsible party they could discover— They have been aching for a head to smash— They thought they saw one, and they smashed Wadsworth’s— The restlessness of men when suffering and their usual conclusion that a change, no matter for what, will benefit them, have been fully asserted in the result of the election— I have toiled hard, but I confess with a bruised spirit & a desponding heart for the principles & conduct of your administration. But the important question is what do the leaders intend to do with their victory. First, you must not think that they intend to award their induction into office They will operate the result against you at once— They mean Peace — Peace upon the patchwork plan — peace upon the plan of the recognition of a Southern Confederacy— Peace upon any terms — but nevertheless peace— They think they have conquered a peace at the ballot box and if they find it necessary, in order to execute that judgment of the people they will resort to arms in one form or another— This City will probably be pushed into the front of the dreadful assay— And now my dear Sir do not think me officious if I say that to be prepared for such possible emergencies your friends should gather themselves more unitedly and densely about you & your measures than ever— A steady — vigorous pursuit of your present policy, with its appropriated means I believe is the sword that will effectually carve through these artificial but formidable obstacles— You may depend upon it. And in the event of an attack in any form upon your administration a host of strong & resolute hearts will strengthen & support you— 63

Mr. Lincoln received many letters from Republicans inside and outside New York lamenting the election of Seymour. Typical was one from New York Judge James W. White, a family friend and a supporter of General Wadsworth:

Our friends desired me to say, that our late elections have been a bitter reverse, bringing us to the very verge, if not into the abyss itself of that divided North which we have apprehended for so many months; but they also wish me to say, that you, as our leader, can, by giving to this seeming disaster its true interpretation, convert it into a means of ultimate triumph and that you alone can do this.

Only two interpretations can be given to those elections — One — that they indicate, that the people are weary of the war, and willing, for the sake of a delusive peace, to see the country rent in twain, if not into many fragments — the other — that the people consider the Government to have been over lenient and indecisive in its action, and regard success, under the policy it has adopted, as a hopeless impossibility, and have accordingly expressed their discontent by their votes. — The first of these interpretations is too disreputable and degrading to the patriotism of the country to be admitted as correct. — The second one, we trust you will accept and act upon as the true one; and allow me to say, that if you could in your Annual Message intimate, that you so understood those recent expressions of the popular will, the good effects resulting from such a declaration could not be over estimated. It would check the traitorously inclined, and encourage the patriotic. And (if you so regard it) I do not see why something to that effect might not well be said. There could be no impropriety, it appears to me, in stating in the message, “that you had, from the first, desired to manifest to the Rebellious States that you were impelled by no ill will or sectional spirit in summoning the power of the country to put down the wicked conspiracy into which they had entered against the National life; that in using this power you had placed in chief authority — civil and military — men whose well known antecedents were calculated to reassure the South that nothing could be designed by the Government against its lawful rights — and that from the same motive you forbore adopting some war measures that you might lawfully have resorted to from the commencement; that you were sensible, that this leniency might possibly prolong the struggle with Rebellion; but that you thought the advantages accruing from the conclusive evidence it would furnish of the moderation and justice of the designs of the Government warranted you in adopting it, and risking the delays it might possibly invoke; that the policy thus pursued would seem, however, from the course of events to have rather emboldened than disarmed treason; and, judging from recent popular elections, it would appear, also, to be no longer approved at the North; and it would, therefore, be persisted in no longer by the Government.”64

Some factors in the Republican defeat cited by historian Sidney David Brummer included “the harmony in the ranks of the Democrats both New York City and Brooklyn, the October elections in other states, Seymour’s veto of a prohibition bill during his first administration which gained for him the endorsement of a state convention of liquor dealers, and the fear of the draft, which was repeated rumored and even officially announced only to be postponed, thus keeping up the excitement.”65 Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell wrote: “General Wadsworth’s record as a radical abolitionist counted heavily against him with the very body of independent voters who would decide the election. He had been constantly in trouble because of his failure to return fugitive slaves after he became governor of the District of Columbia early in 1862. When the district court sustained the property rights of the owners, Wadsworth flouted the decision publicly.”66

President Lincoln himself analyzed the Republicans’ election losses for Union General Carl Schurz: “I think I know what it is, but I may be mistaken. Three main causes told the whole story. 1. The democrats were left in a majority by our friends going to war. 2. The democrats observed this & determined to re-instate themselves in power, and 3. Our newspapers by vilifying and disparaging the administration, furnished them all the weapons to do it with. Certainly the ill-success of the war had much to do with this.”67

Presidential aide William O. Stoddard wrote an anonymous dispatch for the New York Examiner. His report laid out the political dilemma that was to lead to the Draft Riots of July 1863: “Men in Washington are also waiting anxiously for your new Governor to strike the key-note of his administration of the most powerful state in the Union. There are some indications which give rise to dark forebodings of evil to come, but Mr. Seymour’s friends here claim him pertinaciously as a ‘War Democrat,’ and assure us that all he wants is ‘more vigor.’ We hope that this is true. Should it not be, the friends of the Republic may indeed begin to tremble for the result.”68

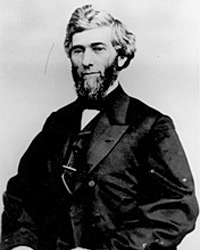

Two years later, the gubernatorial election was less turbulent. Republican Congressman Reuben Fenton scared off any Republican competitors for the 1864 nomination. “When the convention gathered, it was almost a foregone conclusion that Congressman Reuben E. Fenton would be nominated for governor,” noted historian Sidney David Brummer. “Fenton was of the radical wing, but nevertheless had managed to obtain the support of Weed or at least acceptance of him.”69 As usual, Weed would have preferred General John A. Dix, but he did not get his wish.

The candidate of the Democratic Party was less obvious because Governor Seymour had indicated his desire to retire. Among the options discussed were Judges William F. Allen and Amasa J. Parker. According to Seymour biographer Stewart Mitchell, “As soon as he returned to New York [from the Democratic National Convention in Chicago], Seymour found that his unwillingness to accept another, that is a fifth, nomination for governor was laid to his disappointment at having failed to win the first place at Chicago. He might very well have allowed his political enemies to accuse him of sulking in his tent, for he felt that he had worked to very little purpose for two years and he was eager to retire from office. A quarrel within the party was to checkmate him. Dean Richmond, who had forced his nomination on him in 1862, would have been glad to let him go, for the state chairman had backed McClellan and wished to choose a candidate who would fit in with the general. He had his eye on William F. Allen, who had served as chairman of Stanton’s committee to correct the figures for the enrollment in New York. Those friends of the governor who resented Richmond’s failure to force him to accept the nomination at Chicago now took pleasure in crossing their leader from Buffalo. The state chairman had given them McClellan; they would give him Seymour.”70

At the Democratic State Convention in Albany, a resolution of the gratitude of Democrats to Seymour was offered: “They can never forget that it was he, who, in the midst of our disasters and in the face of an overbearing adversary, was foremost in uplifting the banner of constitutional liberty, which he has since borne unsullied through every battle. That it was he who by his wisdom arrested public discord, by his firmness repelled aggressions upon State rights and personal liberty, and by the purity of his public life and the elevation of his purposes, exhibited, in the midst of general corruption and factiousness, the highest qualities of a statesman and a patriot.” The resolution contributed to a surge of Seymour support and a move to offer him the nomination of the party — even though Seymour was expected to decline the nomination. A delegation was instructed to inform Seymour of the convention’s nomination and seek his response. According to historian Sidney David Brummer, “This committee in due time reported that Seymour thought that in view of his impaired health and the demands of his private business, the party ought not to press a nomination upon him, and that therefore he asked the convention to designate some one else; but if the convention insisted upon his being the candidate, he ‘did not feel at liberty at this hour of our country’s peril’ to forbid the use of his name.”71 Seymour’s indecision became a positive acceptance of renomination.

Historian Brummer wrote: “Seymour’s administration of the state government was again an issue, though not as prominent as the year before. Fenton, on the other hand, was assailed because of his abolition record and for voting against the compromise amendments to the constitution in 1861. Slavery and free labor were, of course, discussed; but some Unionist speakers evidently avoided that topic, for Theodore Tilton expressed his regret that so many voices speaking for the Union cause were silent on the question of slavery There were many, however, like Schurz, Greeley, Bryant, Field, Beecher, Sumner and Andrew, who addressed New York audiences and who were not afraid of the subject.”72

The result was a close but relatively quiet election in which the real attention was on the presidential race. Brummer wrote that “the canvas was largely a continuation and a culmination of the three previous contests. The Democrats again claimed to be the upholders of the constitution; they still talked of the perversion of the war by their opponents; they again assailed the arbitrary actions and usurpations of the government, the corruption and extravagance at Washington, the fatuity of confiscation, forcible emancipation, and a war of subjugation.”73

Fenton narrowly defeated Seymour by about 7000 votes — probably on the strength of soldiers’ voting. Loser Seymour was not displeased. According to biographer Stewart Mitchell, “He was genuinely happy not to have to go on for another two years, for he had worked hard and to very little purpose.”74

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 187 (November 2, 1862).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 201.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 208.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 210.

- George Milton Fort, Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column, p. 118-119.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 212.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 215-216.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 250.

- James A. Rawley, Edwin D. Morgan, 1811-1883: Merchant in Politics, p. 182.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 203.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 268.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 424.

- Irving Katz, August Belmont: A Political Biography, p. 118.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 302.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 302.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 303.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 220.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 154 (September 27, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, 1862-1863, p. 304.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 225.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 238-239.

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 156.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 425.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 162-163 (October 7, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 304.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 269.

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 156-157.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 305.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 304-305.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 228.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 229.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 230.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 229 (New York Tribune, October 8, 1862).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 231 (New York Tribune, October 15, 1862).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 236.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 237.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 263-264.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 241.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 241-242.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 250-251.

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 155-156.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 245 (Albany Argus, September 26, 1862).

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 425.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 269.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 232.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 228.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 305.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 269.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 426.

- William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the War Governors, p. 269.

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 159-164.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 268-269 (October 30, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 342.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 249.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 250 (New York Tribune, November 4, 1862).

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 252 (Letter from Thurlow Weed to Horatio Seymour, November 10, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 269-270 (November 3, 1862).

- Henry Greenleaf Pearson, James S. Wadsworth of Geneseo: Brevet Major-General of United States Volunteers, p. 164.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 271-272 (November 5, 1862).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 342.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John Cochrane to Abraham Lincoln, November 5, 1862).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James W. White to Abraham Lincoln1, November 10, 1862).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 253-254.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 254.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume V, p. 493-494 (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Carl Schurz, November 10, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 130 (ca. December 22, 1862).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 395-396.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 372-373.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 418.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 427.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 425.

- Stewart Mitchell, Horatio Seymour of New York, p. 381.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 221.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, Memoir of Thurlow Weed, Volume II, p. 424-425.