columbia house

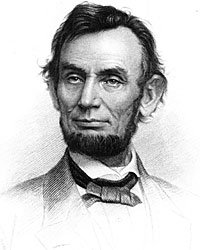

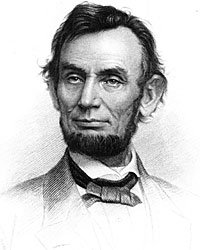

lincoln sketch

General James B. Fry recalled “an anecdote by which he [President Lincoln] pointed out a marked trait in one of our Northern Governors. This Governor was earnest, able and untiring in keeping up the war spirit in his State, and in raising and equipping troops; but he always wanted his own way, and illy brooked the restraints imposed by the necessity of conforming to a general system. Though devoted to the cause, he was at times overbearing and exacting in his intercourse with the general government. Upon one occasion he complained and protested more bitterly than usual, and warned those in authority that the execution of their orders in his State would be beset by difficulties and dangers. The tone of his dispatches gave rise to an apprehension that he might not co-operate fully in the enterprise in hand. The Secretary of War, therefore, laid the dispatches before the president for advice or instructions. They did not disturb Lincoln in the least. In fact, they rather amused him. After reading all the papers, he said in a cheerful and reassuring tone:

“Never mind, never mind; those dispatches don’t mean anything. Just go right ahead. The Governor is like a boy I saw once at a launching. When everything was ready they picked out a boy and sent him under the ship to knock away the trigger and let her go. At the critical moment everything depended on the boy. He had to do the job well by a direct vigorous blow, and then lie flat and keep still while the ship slid over him. The boy did everything right, but he yelled as if he was being murdered from the time he got under the keel until he got out. I thought the hide was all scraped off his back; but he wasn’t hurt at all. The master of the yard told me that this boy was always chosen for that job, that he did his work well, that he never had been hurt, but he had always squealed in that way. That’s just the way with Governor — . Make up your minds that he is not hurt, and that he is doing the work right, and pay no attention to his squealing. He only wants to make you understand how hard his task is, and that he is on hand performing it.1

If Mr. Lincoln associated New York with a bunch of screaming children, he might have had some justification. In August 1864, President Lincoln was beset even more than normal by problems — many of them generated by politicians in New York. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote: “There is no doubt a wide discouragement prevails, from the causes adverted to, and others which have contributed. A want of homogeneity exists among the old Whigs, who are distrustful and complaining. It is much more natural for them to denounce than to approve, — to pull down than to build up. Their leaders and their followers, to a considerable extent, have little confidence in themselves or their cause, and hence it is a ceaseless labor with them to assail the Administration of which they are professed supporters.” Added Welles: “The worst specimens of these wretch politicians are in New York City and State, though they are to be found everywhere.”2

The politicians to whom Welles referred were generally the good guys. Other politicians were even more unsavory. The New York State Legislature in 1860 was notorious for its corruption. The Board of Aldermen was worse. “Our city legislators, with few exceptions, are an unprincipled, illiterate, scheming set of cormorants, foisted upon the community through the machinery of primary elections, bribed election inspectors, ballot box stuffing, and numerous other illegal means,” the New York Herald editorialized in 1860. “The consequence is that we have a class of municipal legislators forced upon us who have been educated in barrooms, brothels and political societies; and whose only aim in attaining power is to consummate schemes for their own aggrandizement and pecuniary gain.”3 When some New Yorkers suggested that an investigation into the Board of Aldermen, Tammany Boss Bill Tweed responded defensively: “We are not answerable for the conduct of those who, either from malice or because they are irretrievably bad, or because they desire to occupy the offices which we now hold, circulate stories calculated to injure those among us who are known to be among the best and firmest of our citizens.”4

The opinion of Tweed, who later set new records for city corruption, might be discounted. New York politicians were a scheming lot who mixed politics, patronage and principle in unequal measures. The New Yorkers with whom Mr. Lincoln dealt were often childish, peevish, impatient, and impetuous. But despite their unpleasant behavior, Mr. Lincoln had little choice but to use their talents and resources for his own patriotic purposes. But telling the good guys from the bad guys was difficult. It was hard enough to tell to what party and what faction a politician owed his current loyalty. Indeed, it was hard to follow Civil War politics in New York without a scorecard.

Consider former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson, who sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1860 as a “hard” and “anti-Regency” Democrat sympathetic to the South. By 1864, Dickinson was a “War Democrat” who came close to being nominated for Republican or “Union” nomination for Vice President. Before the Civil War John A. Dix was also a Democrat in good standing — serving as Secretary of Treasury for the final months of the Democratic Buchanan Administration. But under President Lincoln, General Dix was regularly deployed to handle politically difficult situations.

Or consider A. Oakey Hall, who was elected district attorney of New York in 1863 with Republican and Mozart Hall support. Hall had started out political life as a Whig. He became a Know-Nothing in the mid-1850s before joining the Republicans. But with election to city office, the dapper Republican became a dapper Mozart Hall Democrat when he was elected District Attorney. Eventually “Elegant Oakey” switched to Tammany Hall clothes.

The Republicans in New York also came in many outfits. Many of the former Whigs were closely aligned with Secretary of State William H. Seward and Albany Evening Journal editor Thurlow Weed. Many of the former ‘soft” Democrats in the Republican Party were more radical than the former Whigs. Republicans often sought to balance these factions. In 1860, for example, they nominated former Whig State Chairman Edwin D. Morgan for Governor. While Morgan was close to Thurlow Weed, the nominee for lieutenant Governor, Robert Campbell, was in the anti-Weed camp.

Democrats took advantage of splits in the old Whig camp caused by differences over emancipation and civil liberties. In 1862, they encouraged those former Whigs who had formed the Constitutional Union Party to hold their convention the day before the Democratic one and nominate a statewide ticket that the Democrats subsequently endorsed. In return the Democrats endorsed two “Silver Gray Whigs” — former Governor Washington Hunt and James Brooks — as nominees for Congress. Representing New York City, Brooks became one of the most prominent opponents of Lincoln Administration policies — as both an editor of the New York Express and a politician. He was a Whig turned Know-Nothing turned Democrat. In 1860, he supported Mr. Lincoln’s candidacy. In 1864, he supported George B. McClellan.

Taking a different path was Congressman John Cochrane, a Free Soil Party activist who backed Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas as the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina. According to historian Allan Nevins, his “ringing voice, aggressive manner, and proficiency in parliamentary law made him a great asset in Charleston.”5 But by the spring of 1864, General Cochrane had defected to the far end of the Radical Republican spectrum and chaired the radical convention in Cleveland, Ohio. “I am surprised that General Cochrane should have embarked in the scheme,” wrote Navy Secretary Welles in his diary. “But he has been wayward and erratic. A Democrat, a Barnburner, a conservative, an Abolitionist, an Anti-Abolitionist, a Democratic Republican, and now a radical Republican. He has some, but not eminent, ability; can never make a mark as a statesman.”6

Many New York Republicans were particularly influential on the national scene. Businessman Simeon Draper took over the state Republican chairmanship from Edwin D. Morgan in 1860 and served until 1862 when more Radical Republicans took over the party organization. The wealthy Morgan had been elected Governor in 1858 but kept the post of Republican National Chairman. When Senator Morgan gave up the party post in 1864, it was to another New Yorker, New York Times Editor Henry J. Raymond.

The Democratic National Chairman during this period was also a New Yorker, financier August Belmont. Democratic publicity, fund raising and strategy was coordinated by Belmont and his friends in New York City — men like attorney Samuel L. M. Barlow and Manton Marble, who was editor of the New York World. Belmont was an influential part-owner of that newspaper. Another leading Democratic paper was the New York Daily News, run by sometime Congressman Benjamin Wood with a little help from his brother Mayor Fernando Wood, who headed the Mozart Hall faction of city Democrats. Being a leading Peace Democrat, however, did not stop Fernando from repeated attempts at ingratiating himself with President Lincoln. By April 1863, noted historian Reinhard Luthin, “Wood, who had, shortly before, publicly called himself a staunch Unionist supporter of the war, was delivering an incendiary anti-war harangue to a mob of workingmen at a mass meeting advertised as one ‘opposed to the war for the negro and in favor of the rights of the poor.”7

The Woods weren’t the only brother act. Two Republican Conkling brothers — Roscoe and Frederick — served in Congress as Republicans in 1861-63. Roscoe in particular made himself useful to President Lincoln, but he was feisty enough for both brothers — picking fights with the House’s top Republican, Pennsylvania’s Thad Stevens. His brother-in-law, erstwhile Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour, wasn’t very fond of him either.

Upstate, the ties were more likely to be railroad-related. For most of this period, Dean Richmond was Democratic State Chairman — and a leading executive of the New York Central Railroad. Richmond was a tried and true leader of the Albany Regency faction of the Democratic party. So was “Prince” John Van Buren, son of former President Milton Van Buren, who became Democratic State Chairman in 1862. Prince John led the Democratic attack on Republicans and the election of Governor Horatio Seymour. By early 1863, Van Buren had changed his tune. Van Buren, both during after the campaign of 1862, and repeated advocated a convention as the proper means of saving the Union. But now, in a speech at Washington’s birthday banquet of the City of New York, he declared that it was useless to talk of negotiation with the South in view of the latter’s refusal to treat,” noted historian Sidney David Brummer.8

Another friend of the railroads and Democratic railroad executives was Albany Evening Journal Editor Thurlow Weed, who was a prime supporter of Secretary of State William H. Seward. Republican Weed’s support of President Lincoln was less reliable. But at crucial moments, Mr. Lincoln reached out to him — just as Mr. Lincoln did to Weed’s arch rival, Tribune Editor Horace Greeley, another Republican.

Even supporters of the Administration and its war aims had trouble with the newspapers who supported the war. “The Tribune and Post and Independent abound with the most outrageous lies. There is a great deal of carelessness in them,” wrote Frederick Law Olmsted, who ran the United States Sanitary Commission. He added that “there is also, I am sure, a great deal of intentional falsehood….”9 But President Lincoln had enough battles on his hands in the Old South. He could not afford to aggravate hostilities with the press and their political allies in New York.

Reaching out to cantankerous critics in New York became a regular presidential ministry. Mr. Lincoln had to get along with Unitarian Henry W. Bellows, Congregationalist Henry W. Beecher, and Roman Catholic Archbishop John Hughes. He had to reach out to Democratic National Chairman Belmont and Republican National Chairmen Morgan and Raymond. He even attempted to pacify the legendary crank, New York Herald Editor James Gordon Bennett.

These activities required the fortitude of a saint and the dexterity of a trapeze artist. Mr. Lincoln said of one New York official that he checked under his White House bed each night to see if the politician was lurking there in search of additional patronage. Luckily, Mr. Lincoln had the additional patience that New Yorkers demanded of him.

Footnotes

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time, p. 401-402 (James B. Fry).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 130 (August 13, 1864).

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 37.

- Alexander B. Callow, Jr., The Tweed Ring, p. 24.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1869-1861, Volume II, p. 208.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 43.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 377.

- Sidney David Brummer, Political History of New York State During the Period of the Civil War, p. 295.

- Laura Wood Roper, FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, p. 211 (Letter from Frederick Law Olmsted to Charles Loring Brace, September 30, 1862).