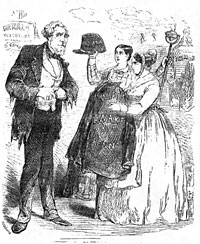

James Gordon Bennett Badgering Abraham Lincoln

News from the States

A Civil War cartoon showing James Gordon Bennett as an American Indian embellished with the Stars and Stripes

James Gordon Bennett, Jr.

New York Herald

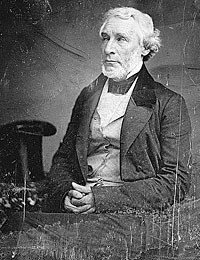

James Gordon Bennett was trouble. Early in his career, he had horsewhipped a fellow editor, James Watson Webb of the Courier and Enquirer. He had also been horsewhipped by Democratic politician Dan Sickles as Bennett’s wife looked on helplessly. But more often, James Gordon Bennett delivered horsewhipping with his pen. Bennett was a gentleman within the confines of his Fort Washington home, far from his newspaper’s offices on Broadway, across from St. Paul’s Chapel. As a publisher, Bennett was erratic but influential.

Indeed, Bennett was a publishing phenomenon who could be ignored only a politician’s peril. According to English journalist Edward Dickey, the Herald was “a power in the country; and though it can do little to make or mar established reputations, yet it has great opportunities of pushing a new man forward in public life, or of keeping him back; and such opportunities as it has, it uses unscrupulously.” But added Dicey, who visited America in 1861, “The real cause…of the Herald‘s permanent success, I believe to be very simple. It gives the most copious, if not the most accurate, news of any American journal. It is conducted with more energy, and probably more capital; and also, on common topics, on which it prejudices or its interests are not concerned, it is written with a rough common sense, which often reminds me of the Times. It has too, to use a french word, the flaire of journalism.”1

Bennett’s journalistic contemporary Charles A. Dana wrote that he was “in many respects the most brilliant, original, and independent journalist I have ever known. Cynical in disposition, regarding every institution, every man, and every party with a degree of satirical disrespect, living through his protracted career in this city with very few friends, and those generally of a mental caliber inferior to his own, ready to affront alike the interests, the prejudices, and the passions of powerful individuals, or imposing parties with a judgment always inclining to be eccentric, and a lawless humor for which nothing was sacred except his own independent, he yet possessed such fresh and peculiar wit, such originality of style, such resources of out-of-the-way reading and learning, such unexpected and surprising views of every subject, such the collection of news, and to employ those able to organize and push that business, that he made himself the most influential journalist of his day; and in spite of enmities and animosities and contempt such as I have never seen equalled towards any man, he built up the Herald to be the leading newspaper of this country, and indeed, one of the great and characteristic journals of modern times.”2 Indeed, Bennett was New York City’s most creative journalist — developing innovations like the city’s first financial page.

Another contemporary journalist, John Russell Young, described meeting Bennett in 1864: “Hair white and clustering, a smooth face soon to have the comfort of a bear, prominent aquiline nose, a long, narrow head with abundant development in perceptive faculties, a keen boring eye which threw arrowy glances; bantering rather than hearty laughter, a firm masterful jaw, talk in a broad Scottish accent, which he seemed to nurse with a relish. His speech had the piquant, saucy colloquialisms which stamped his individuality on the Herald. His manner stately, courteous, that of a strenuous gentleman of unique intelligence giving opinions as though there were aphorisms, like one accustomed to his own way.”3

Bennett wrote out his conception of the Herald in the mid-1830s: “I mean to make the Herald the great organ of social life, the prime element of civilization, the channel through which native talent, native genius, and native power may bubble up daily, as the pure, sparkling liquid of the Congress fountain at Saratoga bubbles up from the center of the earth, till it meets the rosy lips of the fair. I shall mix together commerce and business, pure religion and morals, literature and poetry, the drama and dramatic purity, till the Herald shall outstrip everything in the conception of man.”4

The Herald had a broad circulation base. John Waugh wrote in Reelecting Lincoln: “The Herald was the spiciest paper in America, laced with sex, scandal, and James Gordon Bennett’s erratic opinions. Bennett’s pen, some said, ‘burns at the nib, and its strokes are like the stings of scorpions.’ His paper had the largest circulation of any newspaper in the country, even greater than Greeley’s, and was nearly as potent as the latter in shaping public perceptions in the North.”5

Biographer Don C. Seitz wrote: “Until James Gordon Bennett the elder came into the field, journalism in America was personal. Editors dealt with their public and one another from the standpoint of the individual. Outside of his opponents the editor paid small attention to the things of life. It was left for Bennett to make the newspaper impudent and intrusive. To do this he became the first real reporter the American press had known. He must therefore be considered a recorder rather than a guide or commentator — not that he was deficient in either quality, but because he deliberately made reporting his choice.”6

John Steele Gordon wrote in American Heritage: “Bennett made the Herald nonpartisan in its news articles, sought always to be the first with the news, and sold the paper to a mass audience by having it hawked on the street at a penny (and, later, two cents) a copy. None of these ideas were his own invention, but he molded them into a unique product aimed at a rising middle class that was avid for information about its world.” Gordon noted that Bennett “introduced a dazzling array of more substantial journalistic innovations. He was the first to cover sports regularly. He was the first to include business news and stock prices in a general interest newspaper. Furthermore, although respectable newspaper newspapers weren’t supposed to notice such things, when a beautiful prostitute was murdered in one of the city’s more fashionable brothels, he played the story for all it was worth.”7

“Bennett’s editing made the Herald the nation’s circulation leader within a year after its founding, and even more impressive, he was able to maintain this position,” wrote historians John J. Turner, Jr. and Michael D’Innocenzo. “Bennett exploited crime stories and used sensationalism to win readers’ interest, but he also included economic analysis, made the Herald the first New York paper to offer a special column of telegraphic news, and presented the best Washington correspondence of all the city dailies. Bennett’s straight objective reporting of the news was often outstanding, but his penchant for jocularity, impudence, flippancy, and satire made the paper controversial and the object of much vituperation”8

Eclectic in politics, Bennett supported Republican John C. Fremont in 1856, Simon Cameron for the Republican nomination in 1860, Democrat John Breckinridge in general election in 1860 and, Ulysses S. Grant for the Republican nomination in 1864 and Mr. Lincoln for reelection in 1864. He was part muck-raker and part muck-maker and enjoyed controversy.. His political agnosticism allowed him to attack virtually any politician at will and to support them when necessary — in 1864, he boosted Ulysses S. Grant as a Republican alternative to President Lincoln. He was frequently anti-British and anti-American.

The period between Mr. Lincoln’s election as President in November 1860 and the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 caused many fluctuations in the editorial positions of New York newspapers. Greeley biographer Ralph Fahrney wrote: “Probably no paper experienced a more sudden and embarrassing conversion than the Herald. Editor Bennett had been enlisted in a personal controversy with Greeley and the Tribune for years. Strangely enough, the Herald supported Frémont during most of the 1856 canvass, and the two rival editors for a time met in friendly recognition,” wrote Greeley biographer Ralph R. Fahrney. “With the defeat of the Republicans [in 1856], however, Bennett switched again to support of the Democracy and the Buchanan administration, loyally upholding the Lecompton Constitution and passing Douglas over ‘to the executioner.’ Had his advice been accepted at Charleston and Baltimore, the Democrats would have patched up their internal feud and united with singleness of purpose upon the main objective of crushing the ‘Black Republicans.'”9

Although he had backed Republican John C. Frémont for president in 1856, Bennett did not begin the 1860 campaign as an admirer of Mr. Lincoln. Indeed, according to Charles A. Dana, Bennett’s support of slavery was undoubtedly one of the points of popularity which made the Herald strong with the business interests and the conservative sentiment of the country.”10 According to Bennett’s biographer, Bennett had on many occasions issued orders that the names of certain persons were not to appear in the columns of the Herald. It seems likely that he may have issued an order of this kind respecting Abraham Lincoln, for the Herald departed from its usual policy of complete news coverage of political campaigns by ignoring the man from Illinois who had challenged the seat of Senator Douglas. Bennett viewed Lincoln as just another abolitionist.”11

After Mr. Lincoln was nominated, the Herald reported: “Abram [sic] Lincoln is an uneducated man — a vulgar village politician, without any experience worth mentioning in the practical duties of statesmanship, and only noted for some very unpopular votes which he gave while a member of Congress. In politics he is as rabid an abolitionist as John Brown himself, but without the old man’s courage.”12 Throughout the campaign, the Herald continued to editorialize against the Springfield attorney.

But Mr. Lincoln’s supporters were not deterred; they began one of many missions to convert Bennett. In a letter on June 18 Chicago Press and Tribune co-owner Joseph Medill wrote Mr. Lincoln: “An intermediary had sounded out Publisher James Gordon Bennett and had found him willing to ‘dicker,’ Medill said. Bennett’s ambition, wrote Medill, was to be a guest with his wife and son at the White House, being ‘too rich’ to desire money. Medill thought it best that the Herald should maintain a policy of neutrality, explaining that Bennett’s active support would be of little moment, but he could cause a great deal of trouble unless his guns were spiked. Medill promised to see his ‘Satanic Majesty’ and find out what he wanted.”13 Historian Allan Nevins noted: “This 1860 gesture came to nothing, but the President (who once wrote: ‘It is important to humor the Herald‘) persisted in his efforts to enlist the support of the famous editor. As an intermediary he used Weed who is said to have remarked that ‘Mr. Lincoln deemed it more important to secure the Herald‘s support than to obtain a victory in the field.'”14 Historian James G. Randall wrote: “That Bennett desired favors was shown when he offered the government this fine sailing yacht, the Henrietta. The offer was accepted and Bennett’s son, at the father’s request, was given a lieutenant’s commission in the revenue cutter service under the treasury department.15

Despite Bennett’s political leanings, politicians and journalists favorable to Mr. Lincoln continued to attempt to move Bennett toward a more favorable stance during the campaign. New York Herald reporter Simon P. Hanscom wrote Mr. Lincoln on October 24, 1860:

My budget appeared in the Herald on Saturday last. I have mailed you a copy. Of course you will find some things in it that will amuse you, but it had to be dished for peculiar appetites and in taking advantage of my opportunities and facilities I trust I have done you no injustice. At first I thought I would not publish the paragraph about your visit to Kentucky, but many of your best and most sagacious friends advised that it had better be done. My speculations about the cabinet were added to give the whole thing a sort of Herald tone. The editorial accompanying the letter is quite as important as the letter.

I had a long talk with Mr. [James Gordon] Bennett, about you, after my return and he was pleased at the assurances I made him that you would persue [sic] a conservative course &c. &c. and said he would give you his support with the greatest pleasure, especially if you would make a clean sweep of the present corrupt office holders. Allow me to assure you that you have the fullest liberty to draw, at discretion, upon my cabinet.16

Historian Reinhard H. Luthin noted that in the 1860 campaign, “Conservative New Yorkers, such as James Gordon Bennett, editor of the Herald, backed [Kentuckian John] Breckinridge against the ‘abolitionist’ Lincoln. Bennett waged a bitter campaign against union with the Douglasites: ‘The Albany Regency want to get Breckinridge into their clutches, that they may cheat him as they…cheated [Daniel S.] Dickinson.’ This did not discourage Mayor [Fernando] Wood, who redoubled his efforts to fuse all anti-Lincoln forces into a Douglas organization.”17

A more important Herald asset for Mr. Lincoln was his relationship with German-American reporter Henry Villard, whom Bennett hired to cover President-elect Lincoln. Villard was put off by Mr. Lincoln’s uncouth behavior and story-telling but the access he was granted by the President-elect provided good copy for the Herald and a sharp contrast to its unfriendly editorials. Bennett biographer Oliver Carlson wrote that “the reports from the Herald‘s special correspondent at Springfield were both factual and friendly, while its editorials were biased and denunciatory.”18 Bennett’s “objection to Lincoln was his party and the certainty that it would split the Union. He governed himself accordingly,” wrote biographer Seitz. “Caring nothing about politics for their own sake, he was not intimately informed about the new man. ‘From day to day’ was his motto.”19 Villard, however, was the only reporter who covered President-elect Lincoln day to day on his trip from Springfield to New York in February 1861.

“The case of James Gordon Bennett the elder posed a special problem as to Lincoln’s press relations. Though a thorn in the flesh to the President, it was felt that Bennett could possibly be won over,” wrote historian James G. Randall. “The Herald editor, born in 1795, was pre-eminent in Civil War journalism, but stood apart in a class by himself. His complex personality and shifting positions cannot be defined in a word. His newspaper, known for its spicy journalism, was outstanding in success as judged by its circulation, estimated at about 77,000. The rising importance of this one journal was a kind of phenomenon, though earnest souls were often angered by its content. During the sectional crisis and the war the Herald shifted about, so that a chart of its attitude toward Lincoln and the government at Washington would show sharp peaks and deep troughs. In the crisis before Sumter the paper was pro-Southern (or prosecessionist); then as a diarist remarked, its ‘conversion…[was] complete’ after the April firing started.”20

Historian Ralph Fahrney wrote that the Herald “immediately after the election urged the Republican nominee to allay the fears of the South by repudiating the Chicago Platform, by announcing a determination to enforce the fugitive slave law, and by pledging support to such constitutional amendments as should guarantee to slavery its every demand. If the Republican party would assume the task of ‘reconstruction,’ it might not only save the Union, but retain itself in power for the next twenty years.”21

Biographer Seitz wrote: “When Lincoln’s Cabinet was announced, the Herald made it known that the ‘Seward-Weed’ slate had been smashed and that Lincoln had followed the fatal error of ‘poor [Franklin] Pierce’ by trying to conciliate all elements, predicting that Cabinet clashes would wreck his administration. The predicted clashes occurred, but did not do the wrecking. Lincoln was too good a politician to permit that.”22

The effort to conciliate Bennett continued after Mr. Lincoln moved to Washington. “On the night of the inaugural ball, Stephen Fiske, the Washington correspondent of the New York Herald, asked Mr. Lincoln if he had any message to send to James Gordon Bennett, editor of that paper. Bennett was frankly antagonistic to Lincoln and his administration. ‘Yes,’ answered Lincoln. ‘you may tell him that Thurlow Weed has found out that Seward was not nominated at Chicago,” wrote Lincoln biographer William E. Barton. “Not for some time did the correspondent understand that this was one of Lincoln’s jokes. It was a very serious joke; it was Lincoln’s declaration that he was master of the situation. Thurlow Weed, who had been endeavoring to crowd [Salmon P.] Chase out of the Cabinet, and Seward, who had declined a secretaryship on the very eve of the nomination, had both discovered that Weed had not succeeded either in the nomination or in the control of the executive.”23 But Bennett’s venom was not checked. He wrote in the Herald of President Lincoln’s first inaugural speech:

It would have been almost as instructive if President Lincoln had contented himself with telling his audience yesterday a funny story and let them go. His inaugural is but a paraphrase of the vague generalities contained in his pilgrimage speeches, and shows clearly either that he has not made up his mind respecting his future course, or else that he desires, for the present, to keep his intentions to himself.

The stupendous questions of the last month have been whether the incoming Administration would adopt a coercive or a conciliatory policy towards the Southern States; whether it would propose satisfactory amendments to the Constitution, convening an extra session of Congress for the purpose of considering them; and whether, with the spirit of the statesmen who laid the cornerstone of the institutions of the republic, it would rise to the dignity of the occasion, and meet as was fitting the terrible crisis through which the country is passing.

The inaugural gives no satisfaction on any of these points. Parts of it contradict those that precede them, and where the adoption of any course is hinted at, a studious disavowal of its being a recommendation is appended. Not a small portion of the columns of our paper, in which the document is amplified, look as though they were thrown in as a mere make-weight. A resolve to procrastinate, before committing himself, is apparent throughout. Indeed, Mr. Lincoln closes by saying “there is no object in being in a hurry,’ and that ‘nothing valuable can be lost by taking time.’ Filled with careless bonhommie as this first proclamation to the country of the new President is, it will give but small contentment to those who believe that not only its prosperity, but its very existence, is at stake….24

Historian James G. Randall wrote: “In the first month or so the new administration was watched for indications of its direction or policy, and a surprising amount of Northern comment was distrustful or unfavorable. Editors inevitably pronounced their pontifical judgments, and among these Bennett of the Herald was particularly caustic, declaring that the Lincoln government was interested only in spoils and in pursuing an antagonistic attitude toward the South.”25 The firing on Fort Sumter dramatically changed the attitude of Bennett — although, as usual, the change was only temporary. Bennett summoned his leading Lincoln contact, Henry Villard, from Washington to New York for a meeting. Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave and John Cullen, biographers of Henry Villard, wrote:

Although Villard noted that Bennett’s crossed eyes gave him a ‘sinister, forbidding look,’ the reporter was impressed by the older man’s tall, slender figure, handsome features, and generally imposing appearance. Still, Villard required no extended acquaintance with his editor to perceive that Bennett was ‘hard, cold, utterly selfish,’ and invincibly ignoble. Throughout the drive and dinner (at which Bennett’s twenty-year-old son was the only other person present), the editor plied his guest with questions about Lincoln, about the president’s characteristics, habits, opinions, plans, movements, and about the circumstances of his acquaintance with Henry Villard. It was only after dinner that Bennett revealed the reasons for his summons.

First of all, the editor declared, he wanted Villard to carry message to his special friend the president. The reporter was to assure Lincoln of Bennett’s loyalty to the Union; the Herald would support all measures that the president and the Congress might deem necessary to put down the rebellion as thoroughly and speedily as possible.26

The elder Bennett also offered his the younger Bennett’s yacht,, the Rebecca, for use by the Treasury Department. He wanted James Gordon Bennett, Jr., commissioned a lieutenant in the revenue service. According to Robert S. Harper, “Villard did his work well. Young Bennett went to Washington and was introduced to the President by Secretary Seward. Lincoln wrote a letter of introduction which Bennett carried with him to Secretary Chase’s office. A commission was granted, and Bennett served until May 11, 1862, when he resigned.”27 Still, the old editor’s affections were as turbulent as the sea.

The Lincoln Administration enlisted an unlikely emissary to conduct another chapter in its diplomacy with Bennett. Thurlow Weed, editor of the Albany Evening Journal, was not on speaking terms with Bennett. They failed to converse even when they both lived in the Astor House in New York. The choice of Weed was so unlikely that when his name came up at a White House meeting, according to Bennett biographer Oliver Carlson, “Seward remarked sarcastically that no better man than Weed could be chosen to insure the complete failure of the mission, for Seward knew that next to himself there was perhaps no person in the whole country more repugnant to Bennett than Thurlow Weed.”28

Albany editor Weed reluctantly agreed to go to New York City and seek an interview with Bennett — which was held at Bennett’s Washington Heights home. Weed later wrote: “The dinner was a quiet one, during which, until the fruit was served, we held general conversation. I then frankly informed him of the object of my visit, closing with the remark that Mr. Lincoln deemed it more important to secure the Herald‘s support than to obtain a victory in the field. Mr. Bennett replied that the abolitionists, aided by Whig members of Congress, had provoked a war, of the danger of which he had been warning the country for years, and that now, when they were reaping what they had sown, they had no right to call upon him to help them out of a difficulty that they had deliberately brought upon themselves.”29

Weed countered with a series of stories and facts about Southern perfidy. “No one knew better than Mr. Bennett the truth, the force, and the effect of the facts I presented, but his mind had been so absorbed in his idea of the pernicious character of abolition that he had entirely lost sight of the real causes of the rebellion. He reflected a few minutes, and then changed the conversation to an incident which occurred in Dublin in 1843, at an O’Connell meeting which both of us attended, though at that time not on speaking terms. In parting Mr. Bennett cordially invited me to visit him at his office or house as often as I found it convenient. Nothing was then said in regard to the future course of the Herald, but that journal came promptly to the support of the government, and remained earnest and outspoken against the rebellion.30

Weed adamantly denied that the change in Bennett’s course came as a result of a mob which surrounded the Herald offices on the night of April 15. “Up to the time of my interview with Mr. Bennett, several weeks after the threatened violence, there was no change in the course of the Herald, nor was one word spoken, suggested, or intimated in our conversation conveying the idea of personal interest or advancement. My appeal was made to Mr. Bennett’s judgment, and to his sense of duty as an influential journalist to the government and Union. That appeal, direct and simple, was successful. The President and Secretary of State, when informed of the result of my mission, were much relieved and gratified.”31 A detente with Bennett was important because not only was its circulation the largest in its country, but observed biographer Oliver Carlson, “no other paper was ever able to equal the full and complete war coverage of the Herald. Its correspondents were with every army; the covered every major and most of the minor engagements, both on land and at sea. And the trained staff of experts in the home office were able to supplement the reports from the fronts with detailed information of every kind, thus giving a full picture to their hundreds of thousands of readers.”32

Bennett’s devotion to coverage of the war was unremitting. His enterprise was creative. He boosted circulation with the unique policy of publishing all known war casualties. He ordered his staff: “Get the names of the dead men on every battle field as soon as you can…But that alone is not enough. Get the names of the wounded. Find out their condition, and if possible, ask them if they have any message they wish relayed to their relatives. Get the facts, and get them quickly.”33 He was a generous employer — particularly for those staffers whose enterprise produced a competitive advantage.

As the 1864 election approached, Bennett liked the presidential possibilities of Union generals — first boosting George B. McClellan and later Ulysses S. Grant. After the First Battle of Bull Run, Bennett editorialized: “The war now ceases to be an uninterrupted onward march of our forces southward. The government in a single day and at the Capitol of the Nation, is thrown upon the defensive, and under circumstances demanding the most prompt and generous efforts to strengthen our forces at that point. Every other question, all other issues, and all other business, among all parties and all classes of our loyal people, should now be made subordinate to the paramount office of securing Washington. The loyal states within three days may dispatch twenty-thousand men to that point; and if we succeed in holding the Capitol for twenty days we may have by that time two hundred thousand men intrenched around it. Action, Action, Action! Let our Governor, and state and city authorities, and the state and city authorities of every loyal state come at once to the rescue and move forward their reinforcements without waiting for instructions from Washington.”34

Biographer Oliver Carlson wrote: “To the fury of its rivals, and often to the consternation of the administration, the Herald was forever printing bits of news and gossip well in advance of all others. There were many in Washington who sought in vain to plug the leaks, or who became unduly reticent on future policy for fear the information would somehow find its way to Bennett’s reporters.”35

While relations with Mr. Lincoln remained distant, Bennett developed an unlikely penpal in Mary Todd Lincoln. Bennett had assigned a social gadfly, Henry Wikoff, to cover her summer vacation in Long Branch, New Jersey in 1861. Historian Benjamin Thomas noted that “the Herald published his pryings in a daily column, ‘Movements of Mrs. Lincoln,’ which struck obliquely at Lincoln by ridiculing her. To shield herself from pitiless publicity she sometimes traveled incognito as ‘Mrs. Clark.”36 Mrs. Lincoln was apparently not offended by the coverage because she wrote Bennett on October 25:

It is with feelings of more than ordinary gratitude, that I venture to address you, a note, expressive of my thanks for the kind support and consideration, extended towards the Administration, by you, by a time when your powerful influence would be sensibly felt. In the hour of peace, the kind words of a friend are always acceptable, how much more so, when a man’s foes, are those of their own household,’ when treason and rebellion, threaten our beloved land, our freedom & rights are invaded and every sacred right, is trampled upon! Clouds and darkness surround us, yet Heaven is just, and the day of triumph will surely come, when justice & truth will be vindicated. Our wrongs will be made right, and we will once more, taste the blessings of freedom, of which the degraded rebels, would deprive us.”

My own nature is very sensitive; have always tried to secure the best wishes of all, with whom through life, I have been associated; need I repeat to you, my thanks, in my own individual case, when I meet, in the columns of your paper, a kind reply, to some uncalled for attack upon one so little desirous of newspaper notoriety, as my inoffensive self. I trust it may be my good fortune, at some not very distant day, to welcome both Mrs Bennett & yourself to Washington; the President would be equally as much pleased to meet you. With an apology, for so long, trespassing upon your time, I remain, dear Mr Bennett, yours very respectfully…”37

Mrs. Lincoln was not immune to flattery; Bennett played on this weakness. Biographer Carlson wrote: “Cynical old Bennett instructed his staff to play up Mrs. Lincoln to the limit. This they did — and with a vengeance. She was pictured as taking the lead of Washington society ‘with as easy grace as if she had been born to the station.’ In her purchases at the fashionable at the fashionable stores she displayed such exquisite taste ‘that all the fashionable ladies of New York were astir with wonder and surprise.’ Her state dinner to Prince Napoleon [in August 1861] was ‘a model of completeness, taste and geniality.’ Every glittering phrase, every cloying adjective, every approving metaphor was used to magnify the charms and virtues of Mrs. Lincoln, till they became buffoonery to all but the first lady herself and her fawning friends.”38

In one article, the Herald reported that “Mrs. Lincoln “was thrown suddenly among a number of old-time fashionables, to whom her simplicity seemed rustic and her cordiality ill-bred, and who would gladly have patronized and controlled her. Without any apparent effort, however, the President’s lady quietly ignored her would-be mentors, and took the lead of society with as easy grace as if she had been born to the station of mistress of the White House.” When the First Lady planned a major White House party in early February 1862, “The New York Herald, always the back-stabbing friend of the President’s wife, defended her in a series of editorials which brought the ill-timed function wide notoriety,” wrote historian Margaret Leech.39

In October 1862, Mrs. Lincoln wrote Bennett from the Soldiers Home where the Lincolns stayed in the summer: “Your kind note, sent by Mr Delille, has been received and justly appreciated. I hope to have the pleasure of seeing the gentleman, this morning, as I believe, he speaks of leaving in the afternoon. It is so exceedingly dusty, it is quite an undertaking to visit W[ashington] even from this short distance, however, as he has been the bearer of a note from you, I scarcely feel like having him leave, without seeing him. From all parties the cry for a ‘change of Cabinet’ comes. I hold a letter just received from Governor [William] Sprague, in my hand, who is quite as earnest as you have been on the subject. Doubtless if my good husband were here instead of being with the Army of the Potomac, both of these missives would be placed before him, accompanied by womanly suggestions, proceeding from a heart so deeply interested for our distracted country. I have a great terror of strongminded ladies, yet if a word fitly spoke in due time can be urged in a time like this, we should not withhold it. As you suggest the C[onfederacy] was formed, in a more peaceful time, yet some two or three men who compose it, would have distracted it — Our country requires no ambitious fanatics, to guide the Helm, and were it not, that their Counsels, have very little control over the P[resident] when his mind, is made up, as to what is right, there might be cause for fear.”40

Mrs. Lincoln was connected to a serious problem that had undermined White House relations with Bennett in late 1861. An unscrupulous but sociable employee of the Herald, Henry Wikoff, obtained access to Mrs. Lincoln’ inner circle and hence to the President’s 1861 Annual Message to Congress and leaked it to the Herald. Mary Todd Lincoln’s biographer, Ruth Painter Randall, described Wikoff as “a clever villain with great personal charm and the captivating manners of a courtier.”41 “Wikoff was a clever and polished man of the world, who had inherited a large fortune, gone everywhere and known everyone. It was said that no other American was acquainted with so many of the notables of Europe as the Chevalier Wikoff, as he was usually called,” wrote historian Margaret Leech. ‘This was the social spy whom the Herald planted in the White House — a glittering, middle-aged scapegrace, who had enjoyed all the gifts of life save stability of character.”42

A committee of the House of Representatives launched an investigation and placed Wikoff under arrest. Journalist Ben Perley Poor wrote: “It was generally believed that Mrs. Lincoln had permitted Wikoff to copy those portions of the message that he had published and this opinion was confirmed when General [Daniel] Sickles appeared as his counsel. The General vibrates between Wikoff’s place of imprisonment, the White House, and the residence of Mrs. Lincoln’s gardener, named [John] Watt. The Committee finally summoned the General before them and put some questions to him. He replied sharply and for some minutes a war of words raged. He narrowly escaped Wikoff’s fate, but finally, after consulting numerous books of evidence, the Committee concluded not to go to extremities. While the examination was pending, the Sergeant-at-Arms appeared with Watt. He testified that he saw the message in the library, and, being of a literary turn of mind, perused it; that, however, he did not make a copy, but, having a tenacious memory, carried portions of it in his mind, and the next day repeated them word for word to Wikoff. Meanwhile, Mr. Lincoln had visited the Capitol and urged the Republicans on the Committee to spare him disgrace, so Watt’s improbable story was received and Wikoff was liberated.”43 Whatever the real truth of the episode, Bennett’s Herald and Mr. Lincoln’s White House were both spared further embarrassment.

Although Bennett was not above using scoundrels like Henry Wikoff to collect news about the Lincoln Administration, he also used more legitimate sources. “When the crisis developed in December, 1862, Secretary of State William H. Seward and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, resigning after a Senate caucus had decreed Mr. Lincoln’s cabinet a failure, the Herald was the first paper to have the news, by chance this time, not by enterprise,” wrote Bennett biographer Don C. Seitz. “George E. Baker, disbursing agent of the Department of State, was a fellow-townsman of Seward, from Auburn, New York. So was J.C. Derby, the New York publisher who was then government dispatch agent in New York. To him Baker sent the news while it was still secret. He took the tidings to Frederic Hudson, managing editor of the Herald, who, in turn, conducted him to Mr. Bennett. The astute editor could not believe it. ‘Scanning me closely with those penetrating eyes of his,’ wrote Derby, in his recollections, ‘that could see in two directions, he finally said: ‘I guess it’s true; we’ll print it.'” Seitz concluded that the Herald scored a great ‘beat.’ Lincoln refused to accept the resignations, and legislative power continued to grow less in Washington.”44

The Scotland-born editor has an innate distrust of radicals, who were behind the Cabinet coup attempt. Historian Robert S. Harper wrote: “Bennett, Sr., supported the war effort, as pledged, but still he looked upon Lincoln as a conservative misled by a gang of radicals. As for personal relationship between the two men, there appears to have been none, except through correspondence, in which Lincoln took the lead.”45

On May 21, 1862, President Lincoln wrote Bennett after the Herald published an editorial about Cabinet divisions resulting for General David Hunter’s Emancipation Proclamation in South Carolina: “Thanking you again for the able support given by you, through the Herald, to what I think the true cause of the country, and also for your expressions toward me personally, I wish to correct an erroneous impression of yours in regard to the Secretary of War. He mixes no politics whatever with his duties; knew nothing of Gen. Hunter’s proclamation; and he and I alone got up the counter-proclamation. I wish this to go no further than to you, while I do wish to assure you it is true.”46

Consistency was no more a virtue of Bennett than of Horace Greeley. On June 17, 1862, Bennett editorialized that “in President Lincoln we have found the man who has thus far been able to grapple [with Radical Republicans] successfully.”47 On “May 22, 1863, Lincoln was represented as a strong candidate for the presidency in 1864. On May 28 the word was: ‘Give us Abraham Lincoln for the next Presidency.’ There followed suggestions that the President should ‘at once cut loose from his cabinet (June 6, 1863); on November 3 the verdict was that Lincoln was ‘master of the situation,'” wrote historian James G. Randall. “The tone then changed. On December 16, 1863, the Herald pronounced that Lincoln’s administration had ‘proved a failure’; on December 18 the country had had ‘quite enough of a civilian Commander-in-chief’; on December 21 Old Abe was ‘hopeless’; a long and stinging editorial in which the President was contemptuously mocked as this or that kind of joke; a ‘sorry joke,’ a ‘ridiculous joke,’ a ‘standing joke,’ a ‘broad joke,’ and a ‘solemn joke.’ The Bennett daily then took up for Grant for President in ’64, overlooking the patent fact that Grant’s indispensable function was that of military commander in the field.”48

By August 1864, Bennett wanted Mr. Lincoln replaced. Lincoln biographer Nathaniel Wright Stephenson wrote:” the country had no political observer more keen than the Scotch free lance who edited The New York Herald. It was Bennett’s editorial view that Lincoln would do well to make a virtue of necessity and withdraw his candidacy because ‘the dissatisfaction which had long been felt by the great body of American citizens has spread even to his own supporters.'”49

Both historians David Donald and James G. Randall quoted from a particularly vicious Herald editorial published on February 19, 1864: “President Lincoln is a joke incarnated. His election was a very sorry joke. The idea that such a man as he should be President of such a country as this is a very ridiculous joke. The manner in which he first entered Washington — after having fled from Harrisburg in a Scotch cap, a long military cloak and a special night train — was a practical joke. His debut in Washington society was a joke; for he introduced himself and Mrs. Lincoln as ‘the long and short of the Presidency. His inaugural address was a joke, since it was a full of promises which he has never performed. His Cabinet is and always has been a standing joke. All his State papers are jokes. His letters to our generals, beginning with those to General McClellan, are very cruel jokes. His plan for abolishing slavery in 1900 was a broad joke. His emancipation proclamation was a solemn joke. His recent proclamation of abolition and amnesty is another joke. His conversation is full of jokes….His title of Honest’ is a satirical joke. The style in which he winks at frauds in every department, is a costly joke. His intrigues to secure a renomination and the hopes he appears to entertain of a re-election are, however, the most laughable jokes of all.”50

Bennett did not underestimate President Lincoln or overestimate would-be-President Salmon P. Chase. “Chase overestimates his own resources and underrates the President’s power of self-defense,” wrote Bennett. “Ordinarily Honest Abe does not display much energy and spirit. So long as he is left in peace to read Artemus Ward’s book and crack his own little jokes he is happy; but when the emergency comes Old Abe is generally prepared to meet it.”51 Such editorials did not deter Mr. Lincoln from seeking Bennett’s support or Bennett from seeking another candidate. Bennett had disdain for Chase’s withdrawal, writing: “The Salmon is a queer fish, very wary, often appearing to avoid the bait just before gulping it down.”52 To Bennett’s chagrin, General Ulysses S. Grant seemed even less interested though Bennett promoted him as “the man who knows how to tan leather, politicians and the hides of rebels.”53

By the beginning of the fall campaign in 1864, Bennett saw the political handwriting on the wall — when other New York politicians thought the President politically dead; “Whatever they say now, we venture to predict that Wade and his tail; and Wendell Phillips and his tail; and Weed, Barney, Chase and their tails; and Winter Davis, Raymond, Opdyke and Forney who have no tails; will all make tacks for Old Abel’s plantation, and will soon be found crowing and blowing, and vowing and writhing and sweating and stumping…declaring that he and he alone, is the hope of the nation,, the bugaboo of Jeff Davis, the first of Conservatives, the best of Abolitionists, the purest of patriots, the most gullible of mankind, the easiest to manage, and the person especially predestined and foreordained by Providence to carry on the war, free the niggers, and give all the faithful a fair share of the spoils.”54

According to historian Michael Burlingame, Bennett “in the last days of the 1864 campaign told his readers that it made little difference for whom they voted. While this was hardly a ringing endorsement, the Herald stopped its assaults on the administration and may have thus helped pave the way for Lincoln’s narrow victory in New York state.”55 But President Lincoln had not been passive in seeking a detente with Bennett. As early September 23, Senator James Harlan, who was a top leader of the Republican campaign, told presidential aide John Hay that “Bennett’s support is so important especially considered as to its bearing on the soldier vote that it would pay to offer him a foreign mission for it.”56 The outreach to Bennett by then was fully under way.

In late July, 1864,President Lincoln wrote New York businessman Abram Wakeman, who was Postmaster of New York City : “I feel that the subject which you impressed upon me at my attention in our recent conversation, is an important one. The men from of the South recently (and perhaps still) at Niagara Falls tell us distinctly that they are in the confidential employment of the rebellion, and they tell as distinctly that they are not empowered to offer terms of peace. Does any one doubt that what they are empowered to do, is to assist in selecting and arranging a candidate, and a platform, for the Chicago Convention? Who could have given them this confidential employment, but he who, less then only a week since…declared to Jacquess and Gilmore, that he had no terms of peace but the independence of the South the dissolution of the Union. Thus, the present presidential contest will almost certainly be no other than a contest between a Union, and a Disunion candidate, disunion certainly following the success of the latter. The issue is a mighty one, for all people, and all times; and whoever aids the right will be appreciated and remembered.”57

The last sentence was apparently an allusion to the Herald‘s Bennett — which apparently Wakeman did not mistake. In mid-August, Wakeman wrote President Lincoln that “we have a curious genius in this city by the name of Wm. R. Bartlett — He has interested himself deeply in your success He deals with men who guide public opinion He desires a confidential interview with you, but he would not visit Washington unless invited by you He claims he can give you some information of vital importance, but he must see you and that at your request — I may say he is a friend of Mr. Isaac Sherman and that Mr. S. believes in him Now I have not been able to see Mr Sherman He is out of town and will not return until Monday I would beg to suggest that you write a line saying you would be pleased to see him in Washington and enclose it to me I will, without his knowing or seeing it, first consult with Mr Sherman, and if, upon consultation with him, we shall deem it best to deliver it, then I will do so otherwise, with proper explanations, return it to you This, I think, will be safe Time, Bartlett says, is all important Else I would wait and see Mr S. for it- “. Wakeman then added: “Mr Bennett you will see by the enclosed is in for Commissioners &c to Richmond He says this would elect you I don’t give any opinion.”58 So began a curious dance between Bennett and President Lincoln with [William O.] Bartlett as the dance master.

The importance of Herald was always recognized by others of the President’s supporters, especially when his political situation seemed darkest. One, Green Clay Smith, wrote President Lincoln in early September: “The Herald has not as yet taken position, its columns are uncertain, & destination doubtful[.] Its circulation and influence, in this state especially, are of almost incalculable, and should be wielded in behalf of the Government and your election[.] It must go this way; if nothing has been done, I pray you see some of your friends, and get them to arrange and secure that paper If that is done New York is safe beyond a doubt without it there may be great doubt- “59

Twice in the fall of 1864, New York promoter Bartlett met with President Lincoln about a diplomatic appointment for Bennett. Even though Bennett was often beating him with a stick, Mr. Lincoln had a carrot which he held out to Bennett during the campaign — the job of U.S. Minister in Paris.

Bartlett corresponded with the President, writing him in late October:

August Belmont bet $4.000 night before last that this State would go for McClellan.

Gen. McClellan has been up to Fort Washington and spent a day with Mr. Bennett.

Mr. B. expressed the opinion to me, this morning, that you would be elected, but by a very close vote. He said that puffs did no good, and he could accomplish most for you by not mentioning your name.60

Meanwhile, Bartlett was also communicating with Bennett. On November 4, Bartlett wrote the Herald editor:

I am from Washington, fresh from the bosom of Father Abraham. I had a full conversation with him, alone, on Tuesday evening, at the White House, in regard to yourself, among other subjects.

I said to him: ‘There are but few days now before the election. If Mr. Bennett is not certainly to have the offer of the French Mission, I want to know it now. It is important to me.”

We discussed the course which the Herald had pursued, at length, and I will tell you, verbally, at your convenience, what he said; but he concluded with the remarks that in regard to the understanding between him and me, about Mr. Bennett, he had been a ‘shut pan, to everybody’; and that he expected to do that thing (appoint you to France) as much as he expected to live. He repeated: “I expect to do it as certainly as I do to be reelected myself.”61

Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote that an agent of Bennett, “W.O. Bartlett, Esq., New York, on January 23, 1865, had a telegram from Lincoln. ‘Please come and see me at once.’ And a biographer of Bennet was later to publish a note as having been written by Lincoln on February 20, 1865, to Bennett: ‘Dear Sir: I propose, at some convenient and not distant day, to nominate you to the United States Senate to France.’ Of such a proffer none of the Cabinet nor of Lincoln’s secretaries had knowledge. It seemed, however, in keeping with a certain solidarity of interests for which Lincoln was striving. Thurlow Weed seemed to know who it was that had gone to Lincoln and arranged for his consent to naming a notorious journalistic profligate to represent the American people at a world capital. Weed wrote to John Bigelow: ‘I dare not tell all about the Bennett matter on paper. It was a curious complication for which two well-meaning friends were responsible. Seward knew nothing about it until the [November, 1864] election was over, when he sent for me. I was amazed at what had transpired.’ Thus the fox [Thurlow] Weed. And the wolf Bennett? He sent word to Lincoln that he must respectfully decline to go to Paris as a spokesman for the American nation. So it seemed. And in the New York Herald its readers found no inkling of this news in the diplomatic field. The smooth and diabolical James Gordon Bennett was having more of his kind of fun.”62

Historian James G. Randall wrote: “After many shifts the Herald support was belatedly given to Lincoln in 1864 and it has been supposed that this result was related to Lincoln’s offer to appoint Bennett as United States minister to France. Lincoln’s letter extending the offer was date February 20, 1865. Under date of March 6, 1865 Bennett wrote the President declining the offer but taking special pains to show his ‘highest consideration’ of the President’s attitude in ‘proposing so distinguished an honor.’ Secretary Welles disapproved of the proferred appointment, referring to Bennett as ‘an editor…whose whims are often wickedly and atrociously leveled against the best men and the best causes….'”63

“The widely accepted historical view of Lincoln, Bennett and the election of 1864 begins,” wrote historians John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo, “with a recognition of the editor’s strong opposition to the President, emphasizes the significance of the tender of the ministry to France, and proceeds to the conclusion that this tactic caused Bennett to reverse his previous position by endorsing Lincoln for reelection.” The two historians noted: “The best and most thorough account of the machinations of the secret French ambassadorship offer is presented by David Q. Voight. He concludes that Bennett’s shift to a ‘neutral’ editorial policy really amounted to indirect support of Lincoln, and that ‘as the election grew closer Bennett appeared to grow less critical toward Lincoln and more derogatory of the Democrats. This is by far the most careful and judicious assessment of the situation offered in historical literature.”64

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in his diary on March 16, 1865 that former Postmaster Montgomery “Blair believes the President has offered the French mission to Bennett. Says it is the President and not Seward, and gives the reasons which lead him to that conclusion. He says he met Bartlett, the [runner] of Bennett, here last August or September; that Bartlett sought him, said they had abused him, B. in the Herald but thought much of him, considered him the man of most power in the Cabinet, but were dissatisfied because he had not controlled the Navy Department early in the Administration and brought it their (the Herald‘s) interest.” Welles went on to call Bennett “an editor without character for such an appointment, whose whims are often wickedly and atrociously leveled against the best men and the best causes, regardless of honor or right.”65

Another Lincoln ally, Pennsylvania editor and politician Alexander K. McClure, wrote in Lincoln and Men of War Times: “One of the shrewdest of Lincoln’s great political schemes was the tender, by autograph letter, of the French mission to the elder James Gordon Bennett. No one who can form any intelligent judgment of the political exigencies of that time can fail to understand why the venerable independent journalist received this mark of favor from the President. Lincoln had but one of the leading journals of New York on which he could rely for positive support. That was Mr. Raymond’s New York Times. Mr. Greeley’s Tribune was the most widely read Republican journal of the country, and it was unquestionably the most potent in moulding Republican sentiment. Its immense weekly edition, for that day, reached the more intelligent masses of the people in every State of the Union, and Greeley was not in accord with Lincoln. Lincoln knew how important it was to have the support of the Herald, and he carefully studied how to bring its editor into close touch with himself. The outlook for Lincoln’s re-election was not promising. Bennett had strongly advocated the nomination of General McClellan by the Democrats, and that was ominous of hostility to Lincoln; and when [George B.] McClellan was nominated he was accepted on all sides as a most formidable candidate. It was in this emergency that Lincoln’s political sagacity served him sufficiently to win the Herald as to his cause, and it was done by the confidential tender of the French mission. Bennett did not break over to Lincoln at once, but he went by gradual approaches. His first step was to declare in favor of an entirely new candidate, which was an utter impossibility. He opened a leader on the subject thus; ‘Lincoln has proved a failure; McClellan has proved a failure; Fremont has proved a failure; let us have a new candidate.’ Lincoln, McClellan, and Fremont were then all in the field as nominated candidates; and the Fremont defection was a serious threat to Lincoln. Of course, neither Lincoln nor McClellan declined, and the Herald, failing to get the new man it knew to be an impossibility, squarely advocated Lincoln’s re-election.”66

Journalist Charles A. Dana, who was close to President Lincoln, later wrote: “It is certain that Mr. Lincoln made a great account of the Herald afterwards; and I know of my own knowledge that at one time he tendered to Mr. Bennett the appointment of minister to France. The compliment was declined; but it was appreciated, and I don’t think that after that there was ever a word in the Herald which could have caused pain to Mr. Lincoln.”67 Fellow journalist McClure concluded: “Bennett valued the offer very much more than the office, and from that day until the day of his death he was one of Lincoln’s most appreciative friends and hearty supporters on his own independent line.”68 Bennett’s biographer, Don C. Seitz, quotes Thurlow Weed as saying that “two well-meaning friends” were responsible for the affair of the French offer. Seitz adds: “The surmise left open is that ‘the two well-meaning friends’ may have conveyed some word of the President’s intention to honor the editor during the campaign and so brought about the switch in the Herald‘s attitude….'”69

Bennett’s letter of appointment from President Lincoln was sent on February 20, 1865, but Bennett’s letter of declination was not sent until March 6: “I have received your kind note in which you propose to appoint me Minister Plenipotentiary to full [sic] up the present vacancy in the important Mission to France. I trust that I estimate, at its full value, the high consideration which the President of the United States entertains and express for me by proposing so distinguished an honor. Accept my sincere thanks for that honor. I am sorry however to say that at my age I am afraid of assuming the labors and responsibilities of such an important position. Besides, in the present relations of France and the United States, I am of the decided opinion that I can be of more service to the country in the present position I occupy. While therefore, entertaining the highest consideration for the offer you have made, permit me most respectfully to decline the same for the reasons assigned.”70

Historians John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo asked: “Did the dealings with Bennett on behalf of Lincoln affect the Herald‘s stance in the week prior to the election? Although the Herald apparently retreated from virulent political criticism, it did not endorse Lincoln, as has so often been claimed. But McClellan, and particularly the Democratic platform, were also unacceptable to Bennett. With the inevitable failure of his electoral congress proposal on behalf of Grant, it is not surprising that Bennett ‘dropped out,’ so to speak. If the verbal promises of Lincoln’s bargainers had been as effective with Bennett as has been claimed, one wonders not only why the editor refused to explicitly endorse the President, but why he continued to depict Lincoln as a failure up to and beyond election day.”71

The controversial Bennett still had one friend at the White House. Mrs. Lincoln wrote Abram Wakeman about the reported offer to the editor of the New York Herald to be Minister to France: “The papers appear to think it is one of Mr L’s ‘last jokes,’ the offer made to Mr. lest he [James Gordon Bennett] might consider, that it was intended as a jest, please, do not fail to express my regrets to him — you will understand — even give W[eed] to understand — that I regret, that Mr B- did not accept.”72 Historian James G. Randall saw the difficulties which the Bennett appointment raised:

Bennett was likely to be persona non grata in Paris. Though Bigelow sometimes was impatient with Seward’s policy of speaking softly on French intervention in Mexico, Bennett was becoming fanatical on the subject. His New York Herald criticized Lincoln’s annual message for its neglect of the Monroe Doctrine. Reviving the essence of the forgotten Seward formula — reunion at home through a war abroad—the Herald kept hammering at the theme of combining the Blue and the Gray into an army that would drive the puppet emperor Maximilian out of Mexico and at the same time reconcile the North and the South in a common cause. ‘In the struggles and triumphs of a foreign war,’ as the Herald bluntly put it,’ we shall recement the sunder sympathies of loyal and rebellious states.’

Even though Bennett as Minister to France could thus be expected to work against Seward’s temporizing policy, Lincoln was not a man to forget his political promises. Of course, he may have counted upon Bennett’s declining the appointment. If so, he was taking a risk, for he had no way of knowing for sure that Bennett would decline it. On the contrary, Bennett seemed eager for the offer, if not also for the position itself. In any case, when Lincoln offered it he turned it down. Later Lincoln nominated Bigelow, another experienced newspaperman, a former part owner of the New York Evening Post. The French mission thus happened to fall into able hands.”73

Randall was right. Bigelow combined real diplomatic skills with accomplished French linguistic skills. After Mr. Lincoln’s assassination, noted historian Stephen B. Oates, “the intemperate New York Herald, which had once denigrated Lincoln as ‘the great ghoul at Washington,’ now referred to him as ‘Mr. Lincoln’ and claimed that historians a ‘hundred years hence’ would still be astounded at his greatness.”74 With a trace of irony, Bennett traced the “real origin of this dreadful act” to “the fiendish and malignant spirit developed and fostered by the rebel press, North and South.”75 Bennett continued as publisher of the Herald until 1867 when he relinquished the position to his less distinguished son.

Footnotes

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Spectator of America: A Classic Document About Lincoln and Civil War America by a Contemporary English Correspondent, Edward Dicey, p. 22-23.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 485-486.

- May D. Russell Young, editor, Men and Memories: Personal Reminiscences by John Russell Young, p. 208-209.

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 55.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 138.

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 15.

- John Steele Gordon, “The Man Who Invented the Newspaper”, American Heritage, August-September 2002, p. 25.

- John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo, “The President and the Press: Lincoln, James Gordon Bennett and the Election of 1864”, The Lincoln Herald, Summer 1974, p. 64.

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p. 76.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 488.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 296.

- Chester L. Barrows, William M. Evarts: Lawyer, Diplomat, Statesman, p. 94 (New York Herald, May 22, 1860).

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 63.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 44.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 44.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Simon P. Hanscom to Abraham Lincoln, October 24, 1860).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign, p. 213.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 302.

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 170.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 42-43.

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p. 58 (New York Herald, December 17, 1860).

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 170-171.

- William E. Barton, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 38.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 310-311.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President, Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 313.

- Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave and John Cullen, Titan, p. 147.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 320 (See James M. Perry, A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents , p. 54-55).

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 318.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, The Life of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, p. 617.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, The Life of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, p. 618.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, The Life of Thurlow Weed, Volume I, p. 618-619.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 322.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 342.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 325.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 335.

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 299.

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levit Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 138 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to James Gordon Bennett, October 25, 1861).

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 336-337.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 295-296.

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levit Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 138 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to James Gordon Bennett, October 4, 1862).

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 271.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 290-291.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume II, p. 251-252.

- Don C. Seitz, The James Gordon Bennetts: Father and Son, Proprietors of the New York, p. 187.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 320.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 225 (Letter to James Gordon Bennett, May 21, 1862).

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 332 (New York Herald, June 17, 1862).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 43.

- Nathaniel Wright Stephenson, Lincoln, p. 372 (New York Herald, August 6, 1864).

- David Herbert Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, p. 74 (and James G. Randall, Lincoln the Liberal Statesman, p. 82-83).

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 332 (New York Herald, October 3, 1863).

- Benjamin Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 416 (New York Herald, March 1864).

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 332 (New York Herald, December 16, 1863).

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 332 (New York Herald, September 25, 1864).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 259.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 229 (September 23, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Abram Wakeman [Draft], July 25, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abram Wakeman to Abraham Lincoln, August 12, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Green Clay Smith to Abraham Lincoln, September 2, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William O. Bartlett to Abraham Lincoln1, October 20, 1864).

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 370.

- Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 110.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 44.

- John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo, “The President and the Press: Lincoln, James Gordon Bennett and the Election of 1864”, Lincoln Herald, Summer 1974, p. 66.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 258-259 (March 16, 1865).

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 90-91.

- James Harrison Wilson, The Life of Charles A. Dana, p. 488.

- Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 91-92.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 44-45.

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 321.

- John J. Turner, Jr., and Michael D’Innocenzo, “The President and the Press: Lincoln, James Gordon Bennett and the Election of 1864”, Lincoln Herald, Summer 1974, p. 68.

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters, p. 205 (Letter from Mary Todd Lincoln to Abram Wakefield, March 20, 1865).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, p. 282-283.

- Stephen B. Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths, p. 18.

- Oliver Carlson, The Man Who Made News: James Gordon Bennett, p. 372.