Abraham Lincoln

Stephen A. Douglas

Map of the 1860 Presidential Election

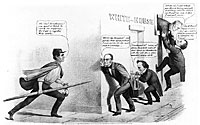

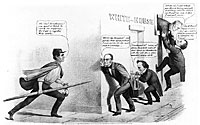

The Republican Party going to the right House

The great match at Baltimore

Storming the Castle, ‘Old Abe’ on Guard

New York was critical to Mr. Lincoln’s victory in 1860 but internal divisions among New York Republicans made victory problematical. Not only political consensus but commercial consensus seemed elusive. “Several groups in New York opposed Lincoln. A sizable number were unwilling to grant the Negro equal status and were not morally opposed to slavery. Others feared that the election of Lincoln would mean civil war or disunion, either of which meant serious economic losses to the industrial and commercial interests of the state,” wrote the authors of A History of New York State. “Most of the great merchants of New York City were in the latter group and opposed Lincoln as a threat to business. The gifted group of Republican leaders in New York were equal to the occasion. Pointing to the moral issues involved and picturing the advantages to commerce and industry which would accrue from protective tariffs, free homesteads and land grants to railroads, the Republicans turned the campaign into a crusade. Lincoln carried New York and won the presidency.”1

“The most formidable Republican presidential contender in 1860 was Seward of New York,” wrote historian Reinhard H. Luthin of then Senator William H. Seward. “Numberless political professionals and his legions of admirers convinced themselves that nothing could stop him. New York’s former two-term Governor would be backed for the presidential nomination at the party’s national convention by his home state’s vote-heavy delegation, by Massachusetts and Maine Republicans, and by such Northwestern states as Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, so many of whose settlers had migrated from upstate New York and New England.”2

Before the Republican National Convention in Chicago in mid-May, Mr. Lincoln had few supporters in New York. Senator Seward was the presumptive candidate of New York Republicans and the national party — and a likely victor in the fall election. Historian Donald Barr Chidsey wrote that “It seemed to Seward’s friends in New York and elsewhere that here was one convention the result of which could safely be foretold. An upset they considered almost impossible. Had not Thurlow Weed told his friend not to be a candidate in ’56, definitely and confidently predicting his nomination and probable election in ’60? And was not Thurlow Weed in personal charge of the New York delegation? That long, dark, silent, man, puffing his long, dark cigars, was esteemed an infallible prophet, incalculably sagacious. He made his full share of mistakes, and perhaps a few more, like all others who are hailed as master-minds in American politics; but the people hadn’t learned this yet.”3

Seward’s organizers thought that there would be few Lincoln supporters in Chicago — which is why they agreed to the “neutral” site to hold the Republican convention. According to Seward biographer Glyndon Van Deusen, Seward’s “lieutenants were everywhere surveying the ground, and a report from Illinois stated confidently that ‘Long John’ Wentworth, a power in Chicago, was ‘right.,’ and that the state would go for Seward.”4 In reality, the Seward organizers had been suckered into choosing Chicago by Illinois Republican State Chairman Norman B. Judd — and they would live to regret the choice of location that effectively Lincoln a home town advantage over Seward. The Seward supporters had other problems, noted historian George H. Mayer: Seward’s “strength was not as formidable as it seemed. The old Free-Soil leaders had always disliked Seward because of his equivocal conduct. They would feel obliged to honor instructions for a couple of ballots, but would be looking for an opportunity to switch. The practical leaders. In fact, Preston King of New York was the only senator who supported Seward wholeheartedly.”5

Meanwhile, noted historian Mayer, “Like a good politician, Lincoln had refrained from public comment on such divisive issues as temperance, nativism, and the Fugitive Slave Law. In a quiet and unobtrusive way, he had engaged in a considerable amount of self-advertisement, which included a 4000-mile tour in 1859, and a notable speech at Cooper Union in New York City, February 27, 1860. Lincoln’s strategy was to avoid offending the supporters of any other candidate. As one Lincoln backer put it: ‘The Republican party has a head and a tail to it and a middle. I name William Seward as the head and Bates as the tail — I say that if the convention selects the head, the tail will drop off; and if the tail, the head will drop off….’ He went on to add that Lincoln was the middle and ‘could hold the head and tail on.”6

Footnotes

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 215.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 62.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 65.

- David M. Ellis, Jams A. Frost, Harold C. Syrett, and Harry J. Carman, A History of New York State, p. 240-241.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 209.

- Donald Barr Chidsey, The Gentleman from New York: A Life of Roscoe Conkling, p. 23.