Independent

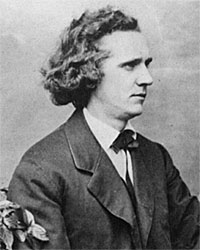

Theodore Tilton was “young, handsome, religious, intense,” wrote historian William Harlan Hale.1 The talented Tilton edited a New York daily, called The Independent,dedicated to emancipation. Andrew A. Freeman wrote in Mr. Lincoln Goes to New York that Mr. Lincoln met the Independent‘s owner and publisher, Henry Bowen, when he came to New York to deliver his address at Cooper Union in February 1860. “While Mrs. Lincoln was the subscriber, her husband was the reader. Beecher was a regular contributor, as was his sister, Harrier Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin….Nathaniel Hawthorne and many other notable Americans contributed to the paper. Its editorial policy was one of strong opposition to slavery which it thought best represented by Seward, not Lincoln.”2

Tilton’s commitment to abolition ran deep. “What was at first, perhaps, only the sympathy of a sensitive boy, abhorring oppression, injustice, and wrong, soon came to be one of the deepest convictions of his nature; and it is not surprising that though his friends were desirous that he should qualify himself to enter the ministry in the Congregational church, he should have preferred the career of a journalist,” wrote a contemporary.3

When businessmen Bowen bought the Independent in 1860, he named his pastor, Henry Ward Beecher, as editor and his fellow parishioner, Theodore Tilton, as editorial assistant. Prior to that purchase, Beecher had already been the author of a “Star Papers” column in the weekly newspaper. Tilton had worked on The Churchman and the New York Observer. “Beecher first knew Theodore Tilton as a clever and attractive young man who reported his sermons. Even before the latter became his editorial assistant Beecher had become fond of him and interested in his future,” wrote Beecher family biographer Lyman Beecher Stowe.4

The two men became devoted colleagues and friends. According to Beecher biographer Paxton Hibben, “There were also practical reasons why Henry Ward [Beecher] found young Tilton so valuable a friend. Tilton was well known in newspaper offices, and no one better than Henry Ward Beecher knew the importance of publicity. What with his auctions of slaves, his ‘Beecher’s Bibles,’ his acrimonious controversies with a score of public men (including the New York City Council for serving champagne at a dinner), and his relationship to the author of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ Henry Ward had not done so badly in keeping in the public eye. But he had reached the point where he really needed a first-class publicity man who could put his heart into the job. Theodore Tilton was precisely that.”5

The devotion ran deep. Bowen, Beecher and Tilton were known as “the Trinity of Plymouth Church.”6 Lyman Beecher Stowe wrote: “Tilton eagerly absorbed the elder man’s views on religion, politics, art, and life in all its phases. Beecher found the young man’s mind brilliant — his character unformed and unstable. He came to treat his almost as a son. Pleased with Tilton’s worked, Bowen and Beecher agreed that he should be acting editor while Beecher was abroad in 1863. On his return from [a vacation in] England Beecher was loath, because of the pressure of his heavy public obligations, to resume any editorial duties other than writing so he proposed that Tilton should continue to edit the paper which should retain Beecher’s name as nominal editor for a year — and after that Tilton should succeed him. This program was carried out with disastrous results to the younger man’s already excessive vanity. He speedily came to believe himself a greater man than his chief and to treat him with patronizing condescension.”7

For a time under Tilton’s editorship, the Independent became a virtual house organ for Beecher and his church. It was a profitable relationship which helped rescue Beecher from debt and from occasional embarrassment. Beecher’s son had been commissioned an officer in the army early in the war but was dismissed from his commission later in 1861 under murky and somewhat scandalous circumstances. Biographer Hibben wrote:

To Henry Ward Beecher it was a staggering blow. He felt humiliated and disgraced beyond any power to save him. In his grief and shame, he went to his friend, Theodore. And Theodore Tilton did not lose an instant. He went straight to Washington, and to the house of Secretary of War Cameron. Cameron had guests to lunch; but Tilton would not be put off. So the Secretary asked Tilton to top to luncheon, also.Theodore Tilton was a man of unquestionable charm. He turned a dull political function into a red-letter day for Cameron’s guests. His wit, his personal magnetism, his physical beauty and rare culture captivated the company. When the guests departed, Tilton begged a commission in the regular army for young Beecher, got it with the Secretary’s signature, and took it himself to the President. He secured Lincoln’s name to the document, and fetched it back to Henry Ward Beecher.8

Unfortunately Tilton shared one of his mentor’s less admirable traits — an inclination to conflict and controversy. Frequently, Tilton was critical of President Lincoln. Presidential aide John Hay wrote in his diary on October 30, 1863: “Theodore Tilton sends an abusive editorial in the Independent & a letter stating he meant it in no unkindliness.”9 Tilton had written: “It was with no pleasure but great regret that I felt impelled by a sense of duty to write the article which appears in this week’s Independent concerning your letter to Mr. [Charles D.] Drake. I write this private line to assure you it was prompted by no personal unkindliness.10

In February 1863, Tilton wrote President Lincoln: “At a meeting in Brooklyn this evening it was unannously [sic] resolved that three thousand men & women in Brooklyn assembled in public meeting say to Abraham Lincoln President of U S. United States Sir ‘Where ever you see a black man give him a Gun & tell him to aid in saving the Republic.'”11

In February 1864, an anti-Lincoln pamphlet was written by circulated by supporters of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase.. According to Chase biographer John Niven, “The pamphlet was not as well received as its authors had hoped. Yet it did attract editorial support for Chase from Theodore Tilton’s New York Independent, the popular religious daily…”12

Tilton was one of those rebellious New York editors who sought to replace President Lincoln as the Republican nominee in August 1864. But after the Democratic nomination of George B. McClellan, Tilton told Anne E. Dickinson: “I was opposed to Mr. Lincoln’s nomination but now it becomes the duty of all Unionists to present a united front.”13 Tilton’s conversion was reflected in his letter of congratulations to President Lincoln on November 12.

I have thanked God every waking hour since the Eighth of November. That day was the greatest in the history of the present generation. On that day Providence so signally interposed to rescue the Republic from its enemies that all Christian patriots are filled with a solemnity of rejoicing. And for yourself, Sir, prayers go up now as never before. The people are with you now as never before. May God keep you in health and strength, and give you the victory!Elicited a popular verdict in favor of annexation, induced the same Congress to vote for what it had voted against. It would add to the glory of the 38th Congress if, in its last session, it should reverse its unhappy decision of the first.Permit me to remind you that no man on the Earth has such an opportunity as yourself for promoting Human Liberty.I cannot doubt that your oft expressed sympathies for the oppressed will inspire you to take official advantage of the verdict of the recent election in favor of Liberty, and to solicit from Congress a final passage of a measure which will be the greatest in American History, after the Declaration of Independence.14

Tilton sent the letter to President Lincoln as an enclosure in another letter to presidential assistant John G. Nicolay: “I would have written to you before this a word of congratulation for the immortal victory of the 8th of November3 for which God be thanked unceasingly! Except that the campaign Exhausted me half killed me speaking as I did, so often and laboriously that on the Saturday night before election I fainted on the platform. Looking back upon that occasion, however, I now feel that I would have been willing to die if by so doing I could have been assured in advance of so great a boon to the Republic as the 8th of November proved to be.”15

It wasn’t just with President Lincoln that Tilton’s relationships were difficult. Beecher biographer, Lyman Abbott wrote that by 1870 “Tilton had proved to be more brilliant as a newspaper writer than sagacious as a newspaper leader. His utterances on religious questions were increasingly distasteful to the orthodox churches; and the orthodox churches were the constituency to which in the past ‘The Independent‘ had appealed.”16 Tilton had become the official editor of The Independent in February 1864. He later edited the Brooklyn Union and founded the weekly Golden Age.

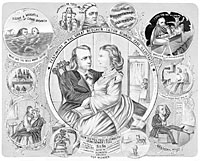

Despite these successes, Tilton’s professional and personal lives headed for a crisis. Tilton “liked to go off on long, strenuous lecture tours, leaving Liz and the children behind. Liz, a former Sunday-school teacher, worshiped ardently at Dr. Beecher’s church, and during Theodore’s long absences Beecher also ministered privately to her,” wrote Horace Greeley biographer William Harlan Hale.17 Lyman Beecher Stowe presented a different version of what happened between the Tilton and Beecher families: “Tilton himself not only advocated free love but practised it with promiscuous vigor, particularly when away on lecture tours. He finally wrote an editorial which, in effect, committed the paper to free-love views, a novel stand for a religious publication.”18 Tilton subsequently charged Beecher with seducing his wife. The resulting scandal was aired in a courtroom and in church pews. It involved a complex myriad of charges, countercharges, retractions and reassertions. It was an unholy mess.

Footnotes

- William Harlan Hale, Horace Greeley: Voice of the People, p. 289.

- Andrew A. Freeman, Abraham Lincoln Goes to New York, p. 15.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 141.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 308.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 142.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 144.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 308.

- Paxton Hibben, Henry Ward Beecher: An American Portrait, p. 157-158.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 104 (October 30, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Theodore Tilton to Abraham Lincoln, October 28, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Theodore Tilton to Abraham Lincoln, February 4, 1863).

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 361.

- Charles M. Segal, editor, Conversations with Lincoln, p. 352(Letter from Theodore Tilton to Anna E. Dickinson, September 30, 1864)..

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Theodore Tilton to Abraham Lincoln, November 12, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Theodore Tilton to John G. Nicolay, November 12, 1864).

- Lyman Abbott, Henry Ward Beecher, p. 290.

- Lyman Beecher Stowe, Saints Sinners and Beechers, p. 309.

- William Harlan Hale, Horace Greeley: Voice of the People, p. 328.